Higher education is an economic necessity, and yet the higher-education system in the United States is under strain today with ever-increasing prices and disappointing completion rates. The results for low-income students and students of color have been profound; low graduation rates may explain why economic inequality continues to exist. Among the institutions most challenged financially and in terms of graduation rates are those that disproportionately serve students from communities of color that are underrepresented in higher education. These institutions form a broad group of minorityserving institutions, or MSIs, which includes historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs; historically black graduate institutions, or HBGIs; predominantly black institutions, or PBIs; tribally controlled colleges and universities, or TCCUs; Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian-serving institutions; Native American-serving nontribal institutions; Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-serving institutions; and Hispanic-serving institutions, or HSIs.

In general, an MSI is categorized as such if a substantial portion of its enrollment is a member of an underrepresented minority group, such as African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian Americans, and Asian American and Native American Pacific Islanders. For the purpose of the analyses presented in this issue brief, public institutions with enrollments by students of color that exceed 25 percent of the total enrollment are considered to be MSIs.

As the United States becomes increasingly diverse, so will the nation’s schools. A majority of babies born in the United States today are children of color, and before the end of this decade, more than half of all youth will be of color. The public K-12 student population already reflects this demographic shift: Just more than half of all students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools are white—the other half are students of color. These demographic changes mean that colleges and universities are poised to have an increasingly diverse student population, which will result in the number of MSIs growing significantly in the years ahead. Therefore, exploring best practices that increase student success within MSIs is vital to communities of color, which will be the majority of the U.S. population by 2043, making their success central to the economic success of our nation.

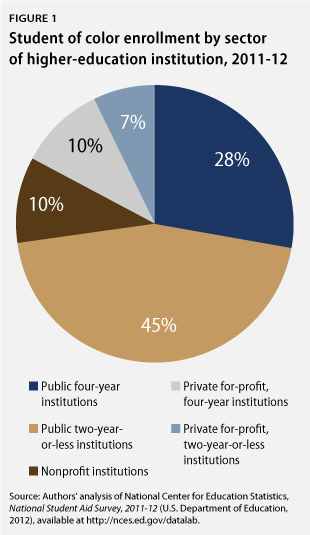

This issue brief focuses on public two-year colleges—commonly referred to as community colleges—and four-year public colleges and universities. The reason for this is simple: 72 percent of students of color enroll in community colleges and four-year public colleges and universities.

Minority-serving institutions play a critical role in educating students of color

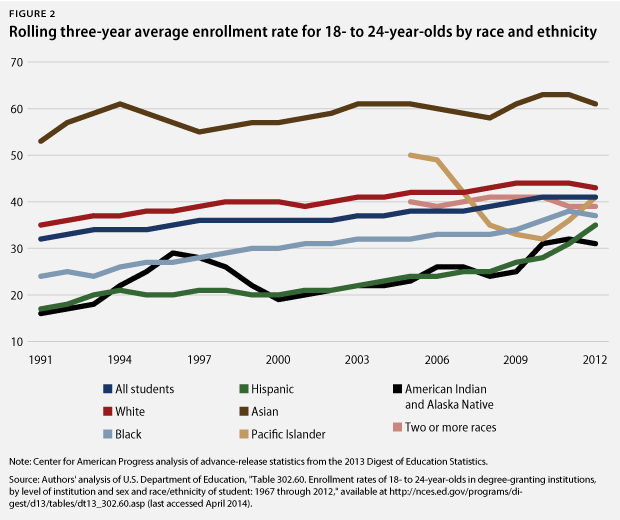

Minority-serving institutions have played a key role in increasing the college-going rates among high school graduates from underrepresented minority groups. Native American, African American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian American, Hispanic American, and Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander high school graduates have historically lacked access to high-quality postsecondary education programs compared to their white peers. And while minority groups have made significant gains in enrollment after high school in recent years, only among Asians Americans do we see college-going rates that exceed those of white, non-Hispanic students. However, that is not likely the case for all Asian subgroups; there are high levels of variation among the Asian American community in education attainment, as well as in other economic indicators such as income and unemployment. For example, almost half of the Asian American community ages 25 and older had a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2010, the highest rate of postsecondary educational attainment compared to any other demographic group. Subpopulation data, however, show a large variation: Indian Americans have a rate of 70 percent, while Vietnamese Americans have a rate of only 26 percent.

Public MSIs provide affordable access to postsecondary education for many low- and middle-income students. For example, community colleges that had 25 percent or more of their enrollments by students of color cost an average of 7 percent less to attend compared to other community colleges for students from families with incomes below $30,000, based on data from the past four years. Meanwhile, public four-year colleges that had 25 percent or more of their enrollments by students of color cost an average of 1 percent less to attend compared to other public four-year colleges for students from families with incomes below $30,000.

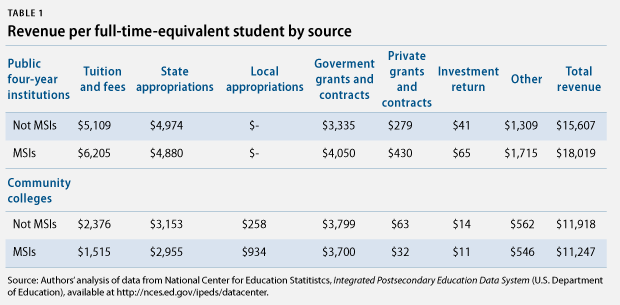

While on one hand affordability is a plus, the relatively low cost of MSIs for low-income students does have consequences, as it limits the tuition and fee revenues available to the institutions to deliver high-quality programs. Community colleges that had enrollments of 25 percent or more by students of color derived a median of $1,515 in tuition and fee revenue per full-time equivalent, or FTE, student compared to other community colleges, which derived a median of $2,376 in tuition and fee revenue per FTE student. Public four-year colleges and universities that had enrollments of 25 percent or more by students of color derived a median of $6,205 in tuition and fee revenue per FTE student, compared to other public four-year colleges, which derived a median of $5,109 in tuition and fee revenue per FTE student.

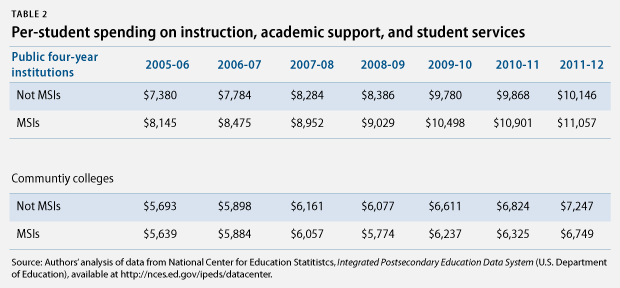

As a result, minority-serving community colleges generated $672 less in revenue compared to other community colleges. By contrast, minority-serving public four-year colleges and universities generated $2,413 more in revenue compared to other public four-year colleges and universities. As a result, minority-serving community colleges spent $500—or 7 percent—less per student on instruction, academic support, and student services compared to other community colleges. By contrast, public four-year colleges and universities were able to spend $912—or 9 percent—more per student in these critical areas.

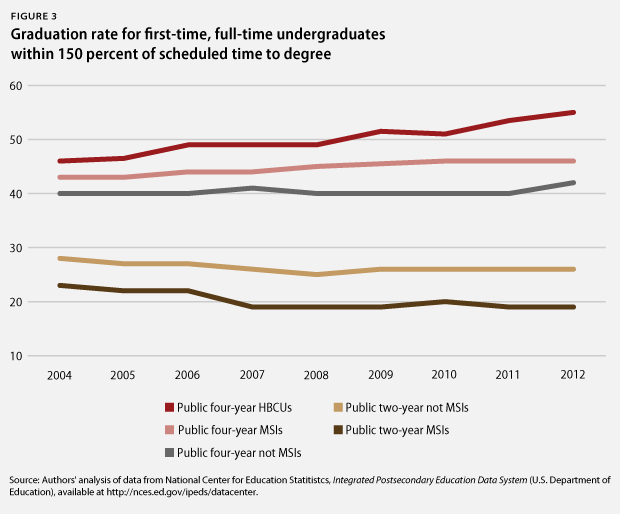

Fiscal constraints have a profound effect on the performance of community colleges and four-year colleges and universities, particularly MSIs. In 2012, the graduation rate for minority-serving community colleges was 27 percent below those of other community colleges. By contrast, the graduation rate for minority-serving public four-year colleges and universities—which, as noted above, have more financial resources—was nearly 10 percent higher than those of other public four-year colleges. Among MSIs, public four-year historically black colleges and universities had graduation rates that were 30 percent higher than public four-year colleges that are not minority serving.

Vital support of minority-serving institutions has proven successful

The federal government has a long history of providing support to minority-serving institutions in recognition of the critical role they play and the difficult challenges they face in expanding opportunities and access to higher education for underrepresented groups. Indeed, today’s historically black colleges and universities were the recipients of the second national investment in higher education, the Morrill Act of 1890. The Morrill Act of 1862, which created land-grant colleges, was the first national investment in higher education. The second Morrill Act—often referred to as the Agricultural College Act—established black land-grant universities that play a vital role in serving low-income and limited-resource families and communities, even as they strengthen research, extension, and teaching in the food and agricultural sciences. Government support to MSIs continues to the present day. These investments have resulted in some MSIs—particularly four-year colleges and universities—receiving significantly more funding from government grants and contracts, which helps them achieve better graduation rates.

In fiscal year 2014, the federal government will provide nearly $800 million through a variety of institutional aid programs authorized under Titles III and V of the Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended. In general, MSIs receive a five-year grant to plan, develop, and implement activities that encourage faculty and academic program development; improve fund and administrative management, including support activities that strengthen an institution’s technological capabilities; support joint use of libraries and laboratories; enable construction, maintenance, renovation, and improvement of instructional facilities; support student services; and implement financial literacy and economic literacy education or counseling services for students or students’ families. Institutions may also use a small portion of the funds they receive to establish or increase an institution’s endowment fund.

President Barack Obama recognized the need for more thoughtful investment in higher education when he proposed funding for the First in the World fund in FY 2014. Under this initiative, innovative strategies and practices shown to be effective at improving college completion and making college more affordable for students and families would be supported. While not specific to MSIs, the First in the World fund would establish a model for making investments based on levels of evidence about the efficacy of specific interventions. In the FY 2015 budget, President Obama called for an additional investment in MSIs through new College Success Grants for Minority-Serving Institutions to support needed investments to develop sustainable strategies, processes, and tools to reduce costs and improve student outcomes.

President Obama’s call for new investments in higher education is based on the key understanding that higher education is a public good, as everyone benefits when one of our citizens obtains a college degree or other postsecondary credential. When this happens on an ever-expanding basis, our nation’s economy becomes more productive, and society benefits from the expanded access. That being said, it is also clear that investments in higher education must be made wisely. Furthermore, increasing access to postsecondary education is an important way to reduce poverty and strengthen our economy. An analysis of 2011 data showed that had we closed racial and ethnic gaps in 2011, average yearly income in the United States would have increased by 8.1 percent; gross domestic product would have increased by $1.2 trillion; and $192 billion would have been added in federal, state, and local tax revenues. Additionally, closing these gaps would have made Social Security more solvent by reducing the long-run deficit by 10 percent—$860 billion—and we would have lifted 13 million people out of poverty.

Strategic investments: Lessons learned from the field

The report, “Measuring the Impact of MSI-Funded Programs on Student Success: Findings From the Evaluation of Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions” by the National Commission on Asian American and Pacific Islander Research in Education, the Partnership for Equity in Education through Research, and the Asian & Pacific Islander American Scholarship Fund provides a compelling example of how the federal government could adopt a process for supporting and evaluating the results of intervention strategies that helps build a learning community—a group of people with shared values who actively engage in learning together from each other—of minority-serving institutions that could dramatically improve outcomes for students and strengthen the institutions themselves.

As noted in the report, the lessons learned for practitioners are clear: Interventions must respond to a specific need or challenge on the campus, a culture of inquiry is critical, evidence of student success should drive replication and scale-up, and assessments of impact on retention and degree completion should be widely discussed. The lessons learned for policymakers are just as clear: Money matters, effective practices should be taken to scale to extend the evidence base, MSIs need support to conduct assessments, and the federal government and foundations should invest in building structures where innovation and scaling up of effective practices can take place.

Relying on outside groups to evaluate practices and disseminate the results of interventions supported with federal funds is not efficient or effective. The U.S. Department of Education has a responsibility to evaluate the practices being supported under the institutional aid programs. As a result of funding constraints, the department has not been able to conduct the kinds of rigorous evaluations that are necessary. Additionally, the department should take steps to systematically gather and disseminate the results of all such evaluations on an institutional improvement website.

Conclusion

Minority-serving institutions play a critical role in our nation’s higher-education system. Too often, these vital institutions have not received appropriate levels of support for the students they serve. As students of color become a larger share of the postsecondary education population, MSIs will become even more important to the prosperity of American families. As such, the more we understand from the lessons learned from today’s MSIs, the more students of color will be able to succeed. But if the nation’s higher-education system is to improve, these institutions must be given the resources and tools necessary to improve. One key tool will be evidence obtained through carefully designed evaluations of the investments that are already being made under Titles III and V of the Higher Education Act and the new First in the World fund. When successful, this effort will lead to greater equity among racial and ethnic groups in educational attainment and a resultant lessening of income inequality as more well-prepared graduates of our nation’s MSIs enter the workforce.

David A. Bergeron is the Vice President for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress. Farah Z. Ahmad is a Policy Analyst for Progress 2050 at the Center. Elizabeth Baylor is the Associate Director for Postsecondary Education at the Center.