This year, in accordance with the Budget Control Act of 2011, the Obama administration released a plan to reduce projected military spending by $487 billion over the next 10 years as part of an effort to reduce the federal deficit. These reductions are a smart first step to rein in the Pentagon’s $620 billion per year budget, which has increased by 46 percent since 2001 and reached levels that exceed peak military spending during the Cold War.

The $487 billion in proposed cuts, however, come from projected increases in the defense budget. As a result, these “cuts” essentially keep the defense budget steady at its current level, adjusted for inflation, over the next five years, before allowing a return to moderate growth thereafter. In short, the Obama administration has halted the explosive increases in military spending that have occurred since 9/11 but has done nothing to bring the budget down from its current level, which remains near historic highs.

As Congress works to come to an agreement to avoid sequestration and put the country on a more sustainable fiscal path, targeted reductions in defense spending must be part of our budget solution. The Defense Department has enjoyed virtually unlimited funding since 9/11, and the Pentagon has continued to fare well over the past two years, avoiding real cuts while domestic programs have seen their budgets repeatedly slashed. Even as the department carries out $487 billion in “cuts,” in 2017 the Pentagon’s base budget will be larger than it is today and larger, in real terms, than it was on average during the Cold War.

A fair and balanced approach to getting our fiscal house in order requires looking for savings in areas that have seen the largest increases, rather than hitting areas that are already struggling. Our domestic programs—which fund our country’s investments in infrastructure, education, health, and scientific research—have already seen real reductions in their budgets while the defense budget continues to grow. The country may be in a time of austerity, but the Pentagon is not.

If carried out correctly, a well-managed defense drawdown can return the Pentagon’s budget to more sustainable levels without harming our national security or our economic recovery. In this issue brief, we recommend $100 billion in responsible reductions over 10 years as an initial target, a modest “down-payment” that would bring the defense budget back to its 2010 level in real terms. While greater savings are both possible and, we would argue, necessary, this brief outlines a menu of the most politically palatable cuts, widely endorsed by organizations on both sides of the aisle, including the Bowles-Simpson Deficit Commission, the Stimson Center/Peterson Foundation, the office of Sen. Tom Coburn (R-OK), the Project on Defense Alternatives, and the RAND Corporation.

As Congress continues its fiscal negotiations, it should consider the following reforms:

- Eliminate the Navy’s buy of the over-budget F-35C jet and instead purchase the effective and affordable F/A-18E/F jet to save $16.62 billion over 10 years

- Reduce the size of our ground forces to their prewar levels to save $16.16 billion over 10 years

- Reform the Pentagon’s outdated health care programs to save roughly $40 billion over 10 years

- Reduce the number of deployed nuclear weapons to 1,100 by 2022 to save at least $28 billion over 10 years

Responsible reductions in defense spending would force the Pentagon to better manage taxpayer money. Over the past decade, despite tremendous increases in defense spending, the Pentagon’s equipment has aged and the size of its combat fleets has shrunk as the department squandered $50 billion on weapons programs that were later cancelled and struggled with cost overruns on many of its major procurement programs. The Pentagon has been so poorly managed that it is unable to even conduct an audit—although it has set a goal of being audit-ready by 2014. The keystone of our country’s national security apparatus cannot keep track of how its money is spent or on what.

The Iraq War is over and the United States is on track to end major combat operations in Afghanistan by the end of 2014. At the same time the federal deficit is increasing, as is the need for investment at home. The United States is adapting a less expansive military strategy and does not face an existential threat abroad. Yet we continue to spend more on defense each year than we did at the peak of the Cold War. Congress’ choice is clear: will it cut $100 billion in unnecessary spending from the Pentagon or $100 billion from programs that protect the poor and vulnerable and support the middle class?

The cuts we outline below represent a politically feasible first step to be taken as part of a fiscal bargain to head off sequestration. That said, these cuts will not address the root causes of the growth in the defense budget. Fundamental reforms to the Pentagon’s procurement processes and personnel policies—including retirement reform—along with examinations of rising operations and maintenance costs and the pervasive use of contractors will still be necessary. But such reforms will never happen while the Pentagon and Congress live in the looming shadow of sequestration and the expiration of the middle-class tax breaks. These steps will allow Congress to reach a workable deal and buy time to deal with more fundamental issues.

Cut the Navy’s plan to purchase 237 F-35Cs (carrier-launched) multirole fighters and instead buy 240 F/A-18E/F fighters—saving $16.62 billion over 10 years

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program was meant to save U.S. taxpayers money by avoiding separate research, design, and testing processes to field fifth-generation aircraft for the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. The program has failed in that regard, as costs have soared due to unforeseen design challenges.

Nevertheless, the Joint Strike Fighter should be built, especially since production of the F/A 22 Raptor—the Air Force’s fifth-generation stealth fighter—was stopped after the production of 187 aircraft. Additionally, many of our allies are waiting to purchase the Joint Strike Fighter, which will improve the ability of the United States to use military power in conjunction with allied forces and lower the unit costs of the jets for the United States.

While the overall F-35 program is strategically valuable, the plane is not an urgent national security imperative given the United States’ already overwhelming tactical air superiority. The United States currently has 3,029 fourth-generation tactical aircraft—three times more than our nearest competitor—and is the only nation fielding a fifth-generation fighter. Our command of the skies is not at risk.

Many in the Navy point out that the F-35’s air-to-air and air-to-ground missions can be capably performed by the existing fleet of F/A-18E/Fs. The only situation in which a fifth-generation, carrier-launched stealth fighter would be needed would be a large-scale strike on a technologically advanced enemy nation, in which case the Air Force’s fleet of F-22s and F-35s, or submarine and surface-launched cruise missiles could pave the way for further nonstealth strikes.

Indeed, the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Jonathan Greenert publicly hinted at this future in a July 2012 article in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine, emphasizing the “need to move from ‘luxury-car’ platforms…toward dependable ‘trucks’ that can handle a changing payload selection.” As Greenert argues, our resources should be focused on improving our missiles, precision targeting systems, and unmanned vehicles rather than marginally improving our carrier-launched multirole aircraft. Indeed, if you accept the Chief of Naval Operation’s analysis, the onus for the Navy is on range, particularly with the development of long-range, anti-access and area-denial weaponry, and the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet jet has a greater range than the F-35C and similar speed.

The FY 2013 budget request calls for the Navy to buy a total of 237 carrier-launched F-35C fighters over the course of the program, totalling $36.828 billion. Given our tremendous numerical and qualitative advantage in tactical aircraft, the budget constraints facing the nation, the Navy’s expensive shipbuilding needs, and the operational environment outlined above, the Navy can capably perform its mission without further developing the F-35C. The F/A-18E/F is a capable, durable, proven airframe that can continue to be improved with electronic and payload enhancements.

Cancelling procurement of the Navy variant of the F-35 would cut $36.828 billion from the defense budget over the next decade, while buying 240 of the less-expensive F/A-18E/Fs would cost $20.208 billion. Therefore, by adopting this plan the United States would save $16.62 billion over the next decade while preserving American air superiority and ground-attack capabilities.

Reduce the size of the Army and Marine Corps to prewar levels—saving $16.158 billion over 10 years

If there is one thing the foreign policy establishment can agree on, it is that the United States will not soon engage in large-scale counterinsurgency or nation-building operations on foreign soil. With the end of the war in Iraq and the planned 2014 withdrawal from Afghanistan, it is natural that the size of our ground forces will come down. The Obama administration’s strategic guidance endorses this view and calls for a reduction in the size of the Army and Marine Corps as part of a shift of focus towards Asia and the Pacific.

In line with this strategic picture, the Department of Defense’s fiscal year 2013 budget request outlined a plan to bring the size of the Army from today’s 547,000 active-duty troops, down to 490,000 troops by 2017, roughly returning to 2002 levels. Likewise, the plan called for a reduction in the Marine Corps from 209,000 active-duty Marines to 189,000 Marines over the next three years, roughly approaching 2007–2008 levels.

The Pentagon’s troop reductions are wise and should be implemented, but there is room to go further. As mentioned, the United States is not likely to face another large-scale ground conflict in the foreseeable future, and the Army and Marine Reserve and National Guard components have proven themselves to be effective should the need arise for wider mobilization. Meanwhile, the low-intensity, asymmetrical conflicts we face today are primarily handled through the use of Special Forces and unmanned aerial vehicles. Finally, the experience gained over more than a decade of war in the Middle East has left the U.S. Army and Marine Corps as the most effective fighting force in the modern world. Efforts can and will be made to retain highly skilled noncommissioned and junior officers so the lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan can be further institutionalized.

Given the budgetary environment, however, along with the strategic picture the United States faces today, further small reductions can be made. The Army could afford to gradually return to 487,000 active-duty troops, where it was before the war in Afghanistan, which would save $2.88 billion over the next decade. The Marine Corps should also return to pre-war levels of 175,000 active-duty personnel, saving $13.278 billion over the next decade. Combined, these troop reductions would save $16.158 billion over the next decade without compromising our national security or our ability to protect our interests and allies abroad. It would also protect our ability to quickly mobilize further ground forces should the need arise.

These end-strength reductions should not in any way impact our commitment to the troops returning from service in Iraq or Afghanistan. In fact, it is exactly this process of rebalancing our budget that will allow us to make the investments needed to provide job-placement, education, and health care to the troops who have sacrificed so much over a decade of war.

Reform military health care—saving $40 billion over 10 years

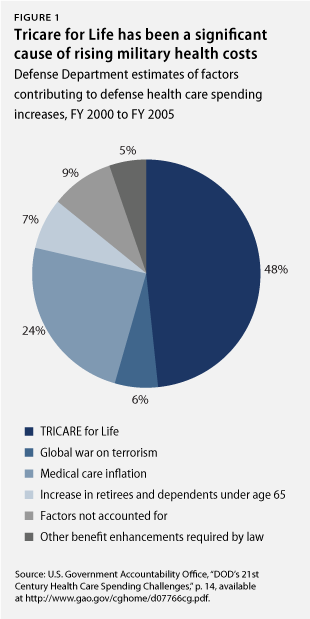

Between fiscal year 2001 and fiscal year 2012, the military health care budget grew by nearly 300 percent and now consumes about one-tenth of the entire baseline defense budget. Most of this cost growth stems not from providing care for active-duty troops, but from caring for the nation’s military retirees and their dependents.

It is imperative that active-duty troops continue to receive health care at no cost and that our country’s military retirees retain access to top-quality health care at a fair price. But the cost growth in the Pentagon’s current health care system is simply unsustainable in the long term. In the words of former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, military health care costs “are eating the Department of Defense alive.”

The Pentagon’s fiscal year 2013 budget request includes smart reforms to the Pentagon’s Tricare health care program that, if implemented by Congress, would be a first step toward restoring fiscal balance to the program. The Defense Department proposes to do the following:

- Raise enrollment fees and deductibles for working-age retirees to reflect the large increases in health care costs since the mid-1990s

- Peg enrollment fees to medical inflation to ensure the long-term fiscal viability of the Tricare program

- Implement an enrollment fee for Tricare for Life, a Pentagon-run plan that augments retirees’ Medicare coverage

- Incentivize generic and mail-order purchases for prescription drugs

Given the looming fiscal showdown and need to come into compliance with the restrictions of the Budget Control Act, Congress should defer to the judgment of our military leaders and pass these responsible health care reforms as a first step toward tackling the Defense Department’s crippling personnel costs. The Pentagon’s proposals would slow the projected growth of the military’s health care costs, resulting in savings of $12.9 billion between FY 2013 and FY 2017. We do not, however, count these savings toward our $100 billion target, as they are included in the $487 billion in cuts mandated by the Budget Control Act.

These reforms alone, however, will not be enough to hold the department’s health care costs steady at current levels, much less reverse the cost growth that has occurred over the past decade. To restore the Tricare program to stable financial footing, the Defense Department should enact measures to reduce the overutilization of services, particularly in the Tricare for Life program, which that has been responsible for most of the Pentagon’s health care cost-growth since 2000.

Such reforms would disincentivize enrollees from seeking unnecessary care, thereby maintaining the effectiveness of the Tricare for Life program while reducing its cost.

Create incentives to reduce the overuse of Tricare for Life services

Tricare for Life resembles private “Medigap” insurance in that it supplements Medicare coverage. By dramatically reducing enrollees’ out-of-pocket expenses, however, Tricare for Life eliminates disincentives to unnecessary care and leads to inflated expenses. To address this issue, President Barack Obama’s Simpson-Bowles deficit commission recommended modifying Tricare for Life so that it will not cover the first $500 of an enrollee’s out-of-pocket expenses and only cover 50 percent of the next $5,000 in Medicare cost sharing. That would reduce overuse of care, saving money for both Medicare and Tricare, the commission found.

The Congressional Budget Office analyzed a similar proposal, in which Tricare for Life would not cover the first $525 of out-of-pocket expenses, and only cover 50 percent of the next $4,725 in costs. Such a policy would “reduce the federal spending devoted to TFL (Tricare for Life) beneficiaries” by about $40 billion over 10 years.

Reduce the number of nuclear weapons—saving $28 billion over 10 years

Our massive nuclear stockpile—1,722 deployed warheads as of September 2012—is a relic of the Cold War. Our nuclear arsenal is expensive to maintain and largely useless in combating the threats facing the nation today, and we possess far more warheads than are necessary for deterrence and to ensure second-strike capability. Unsurprisingly, the Pentagon’s strategic guidance document, released in early January 2012, explicitly notes, “it is possible that our deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force.”

As the Obama administration seeks to find responsible reductions in defense spending, our bloated nuclear stockpile presents a tremendous opportunity for savings. Further, with the election over, President Obama, in his second term, has an opportunity to make significant progress on what has become one of his signature policy initiatives: working toward a world free of nuclear weapons.

According to Air War College and School of Advanced Air and Space Studies faculty members Gary Schaub and James Forsyth Jr., the United States can maintain an effective nuclear deterrent with an arsenal of 292 operational warheads and 19 reserve warheads—311 in total. Schaub and Forsyth contend that this number is more than capable of deterring known threats to the United States and hedging against unforeseen contingencies.

In the near term, however, given the partisan opposition to the New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), 311 nuclear weapons may not be a feasible political target, regardless of whether it makes sense strategically or financially.

Earlier this year the Obama administration was reported to be weighing cuts to a more moderate level of approximately 1,100 nuclear warheads. We recommend that the Pentagon reduce the U.S. nuclear arsenal to this level by the year 2022. Such a cut would be a major reduction from the 1,550 deployed warheads mandated by New START and a promising first step towards a nuclear posture more in line with the threats facing the United States.

The total amount of funding allocated to maintain and operate the nation’s strategic nuclear arsenal is difficult to ascertain given the classified nature of the program. In fiscal year 2011, however, the United States spent $12 billion on its Major Force Program 1, which can be used as a very conservative estimate of the nation’s annual nuclear weapons expenditures. This program covers a broad range of nuclear weapons costs, ranging from pay and training for personnel to the cost of procuring the Air Force’s bombers and ballistic missiles. It does not, however, include many expenses stemming from the nuclear complex—such as weapons transport or research and development to design next generation delivery systems—and as a result it underestimates the true cost of our nuclear weapons program.

According to the U.S. State Department, the United States possessed 1,722 deployed warheads as of September 2012. Cutting to 1,100 deployed warheads over the next decade would represent a reduction of just over one-third from current levels, a financially and strategically reasonable step. Even utilizing the very conservative estimate of $12 billion per year in nuclear costs, phasing in a gradual reduction to 1,100 weapons by 2022 would save $28 billion over 10 years.

Conclusion

In recent history, the United States has cut its military expenditures by about 30 percent at the end of major conflicts. President Dwight Eisenhower cut defense spending by 27 percent after the end of the Korean War; President Richard Nixon reduced the budget by 29 percent as we withdrew from Vietnam, and Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton combined to cut military spending by more than 35 percent as the Cold War came to a close.

In analyzing the factors that have and should determine how much the United States can spend on defense, it is clear that the current level of defense spending can be reduced. We face no existential threats abroad at a time when we are long overdue for investment at home. The federal deficit is increasing, and the United States is shifting to a less expansive military posture and ending two wars. President Obama is seen as a strong foreign policy president and polling indicates that the American people support reducing the defense budget. Therefore, as part of a budget deal to reduce the deficit, avoid sequestration, and extend the middle-class tax cuts, the defense budget can be reduced by $100 billion without undermining our economic recovery or national security. The reforms above will not solve the long-term fiscal challenges facing the Pentagon, but they are a responsible, politically feasible first step that can and should be taken now.

Lawrence J. Korb is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Alex Rothman is a Research Associate and Max Hoffman is a Special Assistant with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress.