A column I wrote more than a month ago discussed the fact that the attack on our consulate in Benghazi, Libya is unfortunately not a unique event. More than 90 diplomats have died in the line of duty over the last 32 years. Libya is only one of many dangerous diplomatic duty stations among the more than 270 diplomatic missions we maintain around the world.

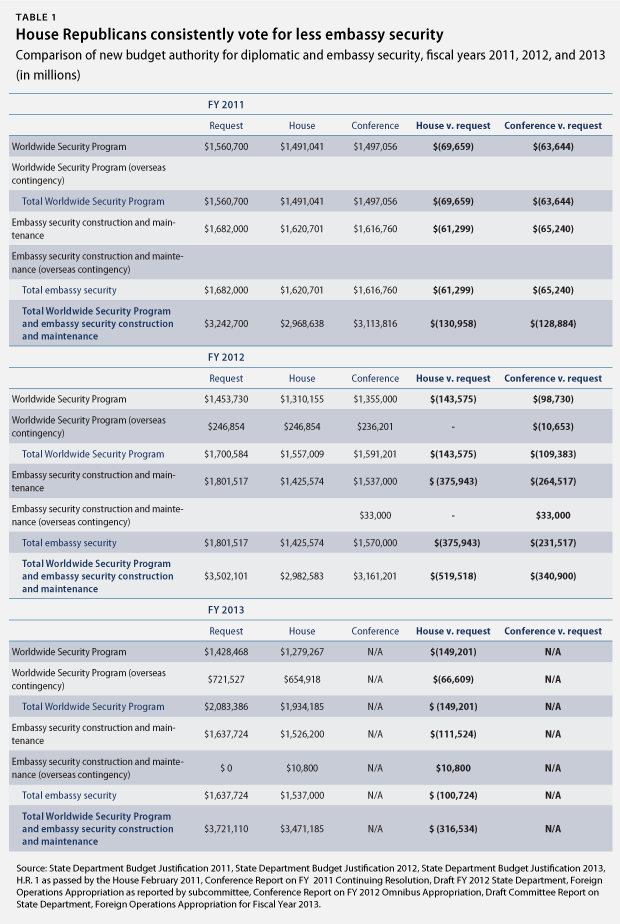

I also mentioned that Congress has failed to recognize that threat. Under pressure from Republicans in the House of Representatives, Congress actually cut the Obama administration’s request for improving the physical security of our embassies by nearly $300 million in the past two fiscal years.

That figure gained a good deal of attention and a lot of requests for more detail and background on the State Department security budget. After spending some time culling through the numbers and reading old General Accountability Office reports and State Department budget justifications, I concluded that the picture that emerges adds significant perspective on the tragedy in Benghazi; the role Congress played in determining the current preparedness of the State Department to cope with such tragedies; and the continuing challenge we face in reducing the threat posed to our diplomats—particularly in those nations that are struggling to build stable, nonviolent societies.

More about the numbers

The first point the additional research revealed is that our efforts to protect diplomats go well beyond strengthening the physical plant of embassies and other facilities. An elaborate and layered network of resources both within the U.S. government and in the military and police forces of host nations serve to protect Americans serving overseas. The heart of this network is the Worldwide Security Program, which includes 1,700 diplomatic security personnel and an annual budget of more than $1.5 billion. This program, and the Embassy Security, Construction and Maintenance program are the principal resources that the State Department relies on to protect overseas personnel.

The second point is that Congress has made deep cuts in both programs in the last fiscal year and the one before that, and it’s threatening to make additional deep cuts in the current fiscal year. In FY 2011 the Congress cut $129 million from a $3.24 billion request. In FY 2012 they cut $341 million out of the $3.5 billion requested. For FY 2013, which began this month, the House voted for a $316 million cut from the administration’s $3.7 billion request; the House and Senate have not yet reconciled their difference in conference committee. (see Table 1)

The third and most important point is that this policy of cutting the State Department’s security programs has been largely driven by the House of Representatives. Had the House funding levels been adopted by the House-Senate Conference Committee, the cuts to State Department security would have been even greater. This was particularly true in FY 2012, when the State Foreign Operations Appropriation bill reported from subcommittee (the legislative vehicle used as the House position in the conference negotiations with the Senate) contained cuts of $520 million in security programs, as opposed to the $341 million cut that came out of the conference.

In the current fiscal year, both House and Senate Committees have produced State, Foreign Operations appropriations bills, but these have not yet been considered on the floor of either body, and the State Department, along with all other Departments and agencies in the government, is being funded under the authority of a continuing resolution passed by Congress before they returned home to campaign in late September.

Appropriators hope to replace the continuing resolution with actual appropriation legislation during the so-called “lame duck” legislative session scheduled for after the election. They will use the bills that have been considered in committee as the basis for putting together a conference report. The House bill cuts $316 million from the request, while the Senate funds the full request for Embassy Security and trims $70 million from the Worldwide Security Protection. If the conference splits the difference between the two positions, State will absorb slightly less than a $200 million cut in the two programs in the coming year.

Lessons not learned on embassy replacement

What are the real world consequences of these cuts? Following the catastrophic bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut in 1983, Secretary of State George Schultz appointed an Advisory Panel on Overseas Security chaired by Retired Admiral Bobby Ray Inman. In its 1985 report the panel noted:

Unlike most U.S. Government organizations, the foreign affairs agencies are required by the nature of their missions to locate their facilities in overseas environments over which the U.S. can exert only limited control and which thus make our presence highly vulnerable to a number of potential threats.

The panel determined that of the 262 posts that the State Department at that time maintained around the world, “126 of the posts require replacement.” They concluded:

[T]his situation cannot be allowed to continue unchanged. As shown by the bombings and takeovers of our embassy buildings in the Middle East in recent years…there are simply too many risks to our diplomatic personnel and activities at posts with these vulnerabilities to allow these buildings to remain potential targets for such threats.

The panel recommended replacement or renovation of the 126 high-risk posts within a seven-year time frame.

Fourteen years later, following the simultaneous 1998 bombings of the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that killed 220 people and injured more than 4,000 people, Secretary of State Madeline Albright appointed another panel headed by Admiral William Crowe. This group reported that “many of the problems identified in [the Inman] report persist. Adequate funds were never provided to implement the Inman recommendations. Instead, there were drastic cuts in State Department appropriations.”

The Crowe panel listed more than 200 bombings and other attacks that had been launched against U.S. overseas missions in the previous decade and stated:

What is most troubling is the failure of the U.S. government to take the necessary steps to prevent such tragedies through an unwillingness to give sustained priority and funding to security improvements…There is every likelihood that there will be further large bomb and other kinds of attacks. We must face this fact and do more to provide security or we will continue to see our people killed, our embassies blown away, and the reputation of the United States overseas eroded.

The panel found that lack of funds prevented full application of security standards and that “far too many of its overseas facilities (including the embassies in Kenya and Tanzania) [are implemented] only ‘to the maximum extent feasible…’”

Following the findings of the Crowe Commission the Government Accountability Office examined the State Department embassy construction efforts and issued a report in 2001. The GAO found that the department had “ranked over 180 facilities it may need to replace.” The fiscal year 2013 Budget Justification the State Department sent to Congress indicates that 88 new embassies or missions have been completed since that time. This would indicate that there are at least 90 embassies or missions that still need to be replaced.

One measure of the threat level to the Americans that continue to work in such facilities is to examine the list of diplomatic postings where funding for new facilities has been approved in just the last few years. The fiscal year 2012 Appropriation funds give some indication of the breadth of the problem we continue to face. That bill funds replacement of 5 missions, including the large U.S. Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, which has been the target of attacks since it opened in 1958.

Most recently the embassy in Jakarta was the target of a large and violent demonstration the week after the attack in Benghazi. There have been numerous terrorist bombing incidents in the city, including three attacks against hotels frequently used by Americans that killed a total of 19 people over the past decade. A bomb attack in 2004 against the Australian Embassy, located less than three miles from the U.S. Embassy, killed 10 people and wounded more than 100. Contractors hope to be able to open the new U.S. Embassy in 2017.

Other facility replacements included in the 2012 appropriation request were for a new embassy in N‘Djamena, Chad and a new office annex and Marine security guard quarters in Abuja, Nigeria. Various Chadian rebel groups have united twice in the past six years to attack and seize portions of the city N’Djamena, and the city streets continue to be the site of regular gun battles between the government and various criminal and political elements. Conditions in Abuja are equally challenging. Just last month the embassy issued the following warning to Americans living in or working in Nigeria:

The U.S. Mission…wishes to remind all U.S. citizens in Nigeria of the continued threat of terrorist attacks, demonstrations, and other violent actions in Nigeria…In the past week, large demonstrations have occurred in Kano, Kaduna, Zaria, Sokoto, Niger, and Katsina States. Although these demonstrations generally remained orderly, many protestors held anti-American banners and burned U.S. and Israeli flags. Demonstrations originally intended as peaceful can quickly escalate into violent clashes. Demonstrations and riots can occur with little or no warning…During the past few months, purported terrorist entities have threatened to carry out attacks against government personnel and offices, hotels, all educational institutions, both private and public, especially schools attended by children of prominent and foreign individuals, religious institutions, communications centers, media offices, and mass transit facilities. This year, extremists have attacked many of these locations, killing or injuring hundreds of people.

So the question is, if the State Department is four or five years away from providing secure facilities to embassy workers currently facing the threat levels described in these countries, how severe is the threat for the thousands of individuals working in embassies where no funds have been provided and no construction is scheduled? While I am certain that a list of locations, threat levels, and building vulnerabilities exists, I am also certain that for very good reasons it is classified.

Reducing security officers, training and guards

As I mentioned earlier, providing more secure buildings is only part of what must be done to protect Americans who serve us in official capacities around the world. When we send Americans on official business to other countries, we do so with the understanding that these countries’ governments are sovereign powers, responsible for maintaining law and order within the borders of their country. In return, they are obliged to insure the safety and security of our diplomatic personnel.

To negotiate our security needs with foreign governments, we have a unit within the State Department called the Worldwide Security Protection. This unit maintains ongoing liaison with police and military units in all host countries. It works with U.S. intelligence agencies in tracking potential threats and possible activities that may change the threat environment.

But Worldwide Security Protection also supplements the protection that host governments are supposed to provide in a number of important ways. More than half of the 1,700 people who work directly for the program are stationed in missions around the world as regional security officers. Worldwide Security Protection also coordinates with the U.S. Marine Corps in the placement of more than 1,000 Marine Security Guards assigned to about 150 of our more than 270 missions. The program also trains about 30,000 foreign nationals to serve as guards and drivers at missions worldwide. That works out to more than 100 foreign nationals per mission. In addition, the United States on unusual occasion deploys U.S. military units to protect foreign embassies and military personnel.

Use of U.S. military personnel is constrained by two important factors. First, the United States has a finite number of military personnel capable of such missions. Those individual have been used heavily in recent years in Iraq and Afghanistan, forcing more frequent deployments than is good for morale and retention.

More importantly, host governments generally have strong objections to foreign military being stationed within their borders. One might imagine the reaction in the United States if Libya or Egypt insisted on having a battalion of their army deployed with loaded weapons to Washington, D.C. to protect their embassies. Nonetheless, there are certain unusual situations—largely in actual war zones—when regular U.S. military units provide military protection.

It is not entirely clear how the State Department dealt with the $144 million cut from this program last year or how they will manage the $149 million cut that the House is proposing in the current year. The number of people directly employed in the Worldwide Security Protection program has decreased by 70 since 2011—mostly coming from those working in overseas missions. It is expected that funds spent hiring and training guards also declined, putting downward pressure on the level of protection worldwide.

The consequences of poor security

Would additional security funding have prevented the attack in Benghazi? We simply don’t know. Improvements in the security of the facilities in Benghazi were not on the list of improvements sent by the State Department to Congress when the 2012 budget was submitted in February of 2011, either in terms of replacement of that facility or in the “compound security” program, which makes temporary facility upgrades to harden missions until complete replacement can be undertaken.

But that list was drafted months before the uprising against the Qaddafi regime and the dramatic changes that took place in the security situation in Libya. Whether additional steps would have been taken at Benghazi if the full amount requested by the State Department had been appropriated is merely speculation at this point, but clearly some upgrades could have been reprogramed from the facilities originally scheduled if the additional $230 million requested for Embassy Security and Construction had not been deleted from the budget.

What is clear is this: Significant resources that might have gone toward hardening foreign missions against attack in both 2011 and 2012 were taken out of the budget by Congress in a decision driven largely by the House. What is also clear is that misplaced sense of priority is likely to happen again this year unless Congress, and the House in particular, changes course.

It is also clear that the number of security officers and embassy guards available to the State Department and ambassadors in the individual missions is smaller than what the Department told Congress they needed. That means that when one ambassador or his regional security officer insists to the department that they need more resources, the only option is to take resources from another mission also vulnerable to attack.

What this paper has hopefully imparted to the reader is that the security of diplomats is a global problem and one that has suffered from insufficient resources for many years. Diplomacy is always a dangerous business, but representing our country overseas is at present much more dangerous than it needs to be. The list of more than 90 U.S. diplomats who have died in the performance of their duty over the last 32 years that I printed in my previous column will grow to more than 100 if Congress does not face up to the problem of financing the needed upgrades.

Scott Lilly is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.