Many American families have been pushed to the financial brink. As the costs associated with key pillars of family economic security have risen dramatically in recent years, incomes have stagnated.1 Some 43 percent of U.S. households—or 50.8 million households—are unable to afford basics such as food, housing, health care, and child care.2

Families with children in particular have been hit hard by rising costs and flat wages. Diapers alone can cost about $1,000 per child each year.3 In 2014, parents in the lowest-earning 20 percent spent nearly 14 percent of their income on diapers.4 The average price of tuition for an infant in center-based child care is more than $11,000 per year—nearly three-quarters of the earnings of a full-time worker making the federal minimum wage.5

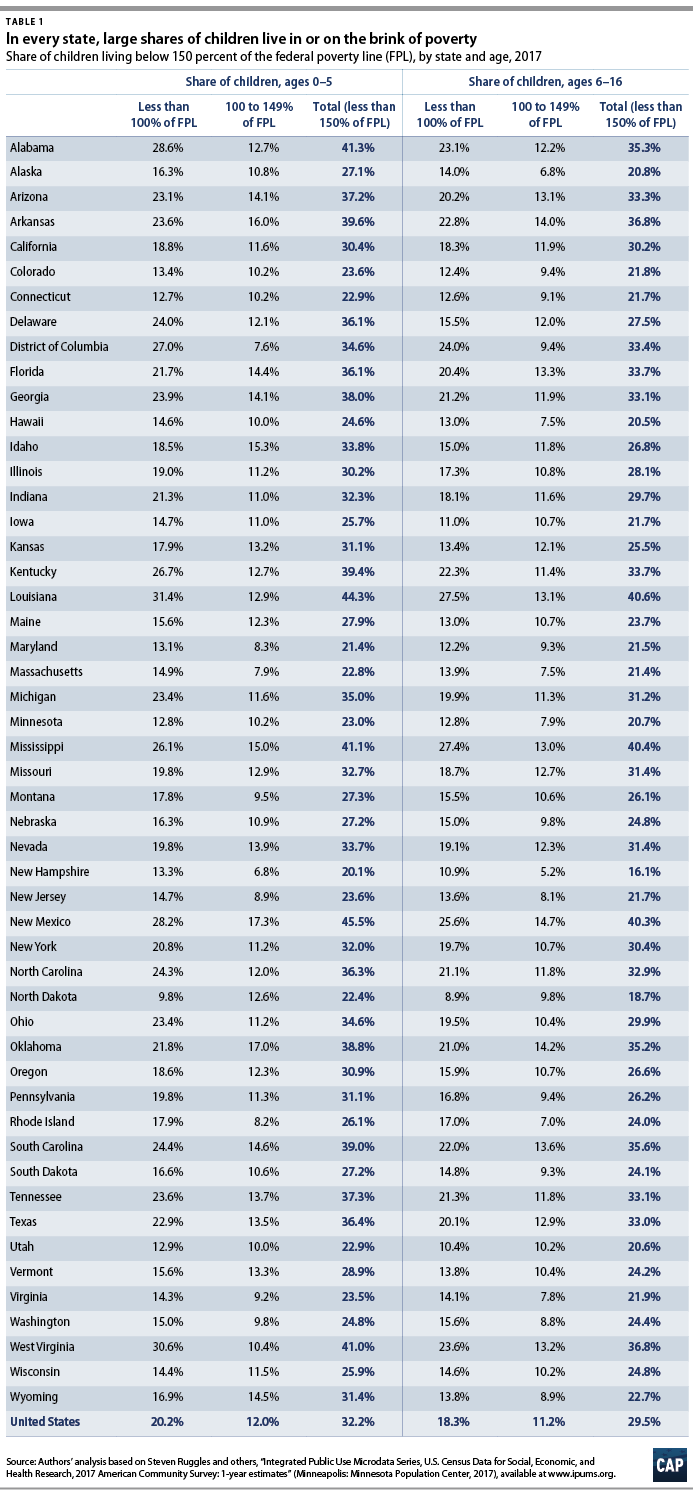

The problem is particularly acute for families with young children. Children under the age of six are in the most critical years for brain development, and in 2017, nearly 1 in 3 of these children were poor or on the brink of poverty. In some states, this share was more than 4 in 10.6 (see Table 1) In fact, the birth of a child is one of the leading triggers of a poverty spell in the United States.7

To combat this problem, state policymakers can create or strengthen a key policy tool: the child tax credit (CTC). A CTC can improve family economic security, reduce child poverty, and make state tax systems more progressive. It can also counteract the harmful effects that the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) had on some families with children.8

What are the consequences of childhood economic insecurity?

Economic insecurity can have lasting consequences for children’s long-term health, education, and employment. Research shows that growing up in poverty introduces stressors to children’s rapidly developing brains that can undermine healthy cognitive and social emotional development, with differences in children’s cognitive abilities by income appearing as early as 9 months old.9 Promoting economic security among families with young children helps set children on a path for success in school and beyond. Research has found, for example, that boosting a low-income family’s income by $3,000 per year until a child’s sixth birthday translates into a 17 percent average increase in adult earnings for that child.10 A recent report from the National Academy of Sciences showed how the high incidence of child poverty is detrimental to U.S. society as a whole, costing the economy as much as $1.1 trillion per year—5.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).11 Despite this, in 2016, the United States spent just 2.1 percent of GDP on child-related benefits—such as the CTC, the earned income tax credit, and child nutrition programs—significantly less than what other developed nations spent on these benefits.12

How do states measure up on addressing children’s economic security?

States’ spending on children varies widely. According to the Urban Institute, the state that spends the least per child devotes about one-third as much per child as the highest-spending state, even after adjusting for cost-of-living differences.13 These differences have been driven in part by the decline of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, the key program responsible for delivering cash assistance to poor families with children. While its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), served 76 out of every 100 poor children nationwide in its final year, TANF—which replaced AFDC during the 1996 welfare reform—serves only about 23 out of 100 poor children today because of the program’s inflexible block grant funding.14 In multiple states—including Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas—fewer than 5 out of 100 children living in poverty receive TANF; and in no state do its benefits bring families to even half of the poverty line, leaving a gaping hole in assistance to struggling families with children.15

Research also reveals substantial disparities in state spending by children’s race. For example, low-spending states are much more likely to have higher shares of Latino and American Indian or Alaska Native children.16 Further research uncovers that states with the most restrictive TANF programs have the highest shares of African American residents. A 10 percent increase in the African American share of the population is associated with a roughly 12 percent decrease in a state’s maximum monthly TANF benefit.17

The vast majority of state tax systems exacerbate these income- and race-based inequalities. In 45 states, upside-down tax systems mean that low- and middle-income families pay more in taxes as a share of income than higher-income families. In the 10 states with the most regressive tax systems, the lowest-income 20 percent of taxpayers pay up to six times as much as a share of income as the highest-income 20 percent.18

What can states do?

States can take immediate action by creating or strengthening a state CTC, a key policy tool to tackle childhood economic insecurity; help families afford the high costs of raising children; and make their tax systems less regressive. State CTCs not only enable state policymakers to invest in the next generation and future workforce, but they can also be used to counteract the inequities and shortcomings of federal tax policy in the wake of Congress’ 2017 tax law.

Just as states in recent years have paved the way on policies such as higher minimum wages, state policymakers are forging ahead with CTCs.19 Seven states have already created CTCs with a range of designs and featuring credit values of up to $660 per child.20

State CTCs need not be extremely costly to have a strong effect, given evidence that even a modest boost in income can have substantial positive effects on children’s long-term outcomes. For example, a moderate refundable CTC could prevent families with children from needing to turn to predatory loans—which have an average value of about $375—to meet urgent child-related costs, thus forestalling a downward spiral of debt.21

What does a successful state CTC look like?

States can customize their CTCs to best achieve their goals and fit their budget by varying the age of eligibility, credit amount, and more. A 2015 Center for American Progress report, “Harnessing the Child Tax Credit as a Tool to Invest in the Next Generation,” offers guidance for state policymakers to maximize the CTC’s effect on child poverty and economic insecurity in their state.22

Reaches all low- and middle-income children

Several design features will guarantee that state CTCs reach all children who would most benefit from them. First, state CTCs should be fully refundable—allowing families to receive the full amount even in years when they have little or no state tax liability—to ensure that children receive the credit when their family needs help most, such as when a parent loses a job.23 Second, children should be eligible to receive the credit regardless of whether they have a Social Security number or an Individual Tax Identification Number (ITIN). Third, gradually phasing the credit out at higher incomes can help target resources for the greatest effect while reducing costs.24 Finally, linking both the credit’s value and the phaseout thresholds to inflation or median wage growth will ensure that in future years the credit stays meaningful for states’ low- and middle-income residents.

Delivers an extra boost to the youngest children

Because the first few years of life are critical for children’s brain development—and even modest boosts in income can have a large effect on long-term outcomes—a strong policy option is to create an additional refundable young child tax credit (YCTC) for families with children under a certain age, such as three or six. An additional YCTC would help families afford the many urgent expenses associated with a child’s earliest years of life such as diapers, formula, a crib, or a car seat. Because child-related expenses do not necessarily align with tax time, the YCTC could be made available on a monthly basis through direct deposit or the Direct Express card.

Includes disabled adult children

Compared with families with a nondisabled child, families caring for a child with a disability often face both higher costs and lower earnings because both caregivers and children face difficulty participating in the formal labor market. These challenges often continue for families after their child passes age 17, particularly for families with children who have intellectual or developmental disabilities, many of whom reside in the family home into adulthood.25 To address the difficulties these families face, states could extend their CTCs to disabled adult children, employing the same rules and definitions used under the federal EITC.26

Strengthens an existing credit

While each of the seven states where CTCs already exist have some of the design features discussed above, none currently have all of them. States could strengthen their existing credits based on these recommendations. For example, states could combine all of the above recommendations: make their CTC fully refundable; eliminate the minimum earnings requirement; boost the credit amount, particularly for lower-income families; expand eligibility to include children in a greater age range and/or disabled adult children; and extend the credit to children without ITINs.

Why should states act now?

State CTCs are especially timely for several reasons. First, as tax season got underway in 2019, many taxpayers not only unexpectedly discovered that they would not receive a refund, but some families with children—particularly larger families—also experienced state tax hikes due to congressional Republicans’ 2017 tax law.27 This particularly affected families in Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico, and North Dakota, where state policymakers have not yet taken steps to counteract the effects of the federal tax law.28 But as analysis from the Tax Policy Center shows, state policymakers could use a state CTC to offset this damage. 29 So while state CTCs would greatly help families in any state that has an income tax, they are urgently needed in these four states.

Second, the 2017 tax law also made the federal CTC substantially more generous toward children in middle- and high-income families, while doing little to improve the credit for children in the lowest-income families.30 This is because it is not fully refundable; the federal CTC totally or almost totally excludes nearly 11 million children in struggling families, including nearly 1.5 million in California and 1.3 million in Texas.31 An additional 15 million children receive less than the full federal credit.32

Building on CAP’s 2015 proposal, a new bill in Congress—the American Family Act of 2019—would create a new YCTC of $3,600 per year, or $300 per month, for children under age six while increasing the existing CTC to $3,000 per year, or $250 per month, for children ages six to 18. Families would have the option to receive the credits on a monthly basis.33

By creating or improving state CTCs, state policymakers can counteract the harm done by the TCJA, offset the limitations of the federal CTC, and, most importantly, meaningfully boost economic security for families with children in their states.

Conclusion

When it comes to a child’s formative years of life, research shows that every dollar counts—and modest assistance pays dividends far into the child’s future. State CTCs have the potential to dramatically increase economic security, reduce child poverty, and help families afford the rising costs of raising children. At the same time, states CTCs can reduce the tendency of many states’ tax systems to exacerbate inequality and offset the unequal and even damaging effects that the 2017 federal tax law had on low- and middle-income families. States can take action now—and they don’t need to wait for Congress.

Rachel West is the former director of research for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.