Introduction and summary

In 1997, Megan Doerr began her teaching career as a kindergarten teacher in a low-income elementary school in Minnesota. She was making $25,000 per year and was riddled with student loan debt. In fact, she, as a college graduate, was making less than her mechanic fiancé, who did not have a degree. She soon realized two things: She needed more training and resources to meet the complex needs of her 5-year-old students, and she would have to find ways to boost her salary to pay the bills.

Twenty years later, Megan is now a single mom to a 16-year-old son and still teaches at the same school. She says that as a Korean American woman adopted as an infant, she loves that she’s able to work with children from various cultures and backgrounds, and she draws on her own upbringing to connect with her students, who are ethnically, racially, and linguistically diverse.

To be able to afford to remain in a career she says is her calling, Megan has held various part-time jobs, from teaching after-school programs to working as a trainer for home visiting programs, in addition to working 65 or more hours per week as a classroom teacher. While she loves teaching, she says, “Passion does not put food in your mouth.”

This year, she has maxed out her earning potential on the steps-and-lanes pay schedule, so she will not see another a pay bump apart from a possible biannual cost of living adjustment unless she seeks a doctoral degree. With no pay increases on the horizon and new bills to pay as she plans to buy her first home this fall, she is looking to take on additional work to maintain her current budget—a significant portion of which is dedicated to not only her son but also all the children she teaches.

As Megan puts it, “I don’t see books, snow pants, and shoes for my students as ‘like to haves.’” These are necessities for her kids, and she refuses to see them go without. In fact, she regularly spends more than $2,000 per year on books, clothing, and other school supplies for her kids. She does this as she is still paying off her student loans.1

Megan’s emotional and financial commitment to her students and classroom reflects the weight of her responsibilities and is emblematic of teachers’ experiences across the United States. Teachers are responsible for educating and cultivating today’s students—the future of the U.S. democracy and workforce. By 2020, 65 percent of all jobs in the United States will require postsecondary education or training.2 To be prepared for democratic participation and postsecondary education, students need a strong base in elementary and secondary school, with excellent, meaningfully supported educators in their classrooms. Currently, teacher compensation does not align with the critical role that educators play in building and sustaining the nation’s democracy and middle class.

Indeed, teacher salaries are not commensurate with the weight of this lofty responsibility and the complexity of the skills required to fulfill it. In fact, teachers in the United States are paid far less than individuals in professions that require similar levels of education and skills. A recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report found that U.S. teachers, on average, earn just less than 60 percent of the average salary of other individuals in the United States with comparable educational backgrounds. This was the lowest relative ratio across all OECD countries with available data.3

Teacher compensation in high-needs schools and districts is especially problematic. High-poverty school districts are more likely to be underfunded and lack the resources that educators need to be successful.4 Moreover, students in high-poverty schools need additional academic support for a number of reasons, such as lack of access to high-quality early education, to ensure that they are on a level playing field with their more affluent peers.5 This places additional responsibilities and stress on a teacher’s already full plate. Yet on average, teachers in schools serving low-income students earn less than teachers in schools serving high-income students. While these differences are largely driven by classroom experience and degree attainment, it is still important to recognize the real gap between average salaries in different school contexts.6 More specifically, in the 2015-16 school year, the average salary of teachers in the highest-poverty schools was approximately $4,000 less than that of teachers in the lowest-poverty schools.7 The gap between these two school types is important context for the labor markets surrounding both high-poverty and low-poverty schools.

Despite available research showing that pay increases can influence teachers’ decisions to stay in or leave their school district,8 the pay gap between teachers and other professionals has increased with time—making other career options even more attractive, especially to high-performing college students. Unsurprisingly, within teaching, a recent report from the U.S. Department of Education found that a majority of public school teachers are unhappy with their pay.9 With state and district budgets stretched thin, however, major investments in teacher pay can be a challenge.10

In recent months, teachers in many states—including West Virginia, Oklahoma, Arizona, Kentucky, Colorado, and North Carolina—have organized strikes or protests to demand a greater overall investment in education and higher pay.11 This pattern of collective action has highlighted the issue of insufficient investment in public education and low teacher salaries across the United States, moving school funding issues to the forefront of political debates in advance of the 2018 elections. Even in most states where these important efforts were successful, however, the increase in pay has been conservative, and teacher pay is still significantly lower than the salaries of professions that require similar levels of education and experience. In West Virginia, for example, the state agreed to a 5 percent raise for teachers.12 Given that the average teacher salary in 2016 across West Virginia was $45,622—making it the third-lowest-ranked state in the country—the 5 percent raise would boost the average teacher salary by only about $2,300 annually.13

These large remaining gaps provide an indication that state legislation and action may be insufficient and that federal government officials must step in by raising teacher salaries for those who need it most: teachers in high-poverty schools. Of course, no discussion of how to attract and retain a strong and diverse teacher workforce would be complete without noting other important levers affecting teachers’ day-to-day experiences and decision-making. A coalition of more than 60 research and education organizations developed comprehensive recommendations to modernize the teaching profession, from redesigning teacher preparation programs to creating career ladders.14

This report outlines a first-of-its-kind proposal for the federal government to help dramatically increase teacher compensation in high-poverty schools. The Center for American Progress proposes that the federal government offer an annual $10,000 refundable Teacher Tax Credit to elementary and secondary teachers in schools serving high percentages of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Teacher compensation is too low

The current state of teacher salaries in the United States has an undeniable impact on the well-being of the nation’s public school teachers. The average starting base salary is $41,600, and the opportunity for a dramatic salary increase is limited.15 Based on 2015-16 school year data, the average base teacher salary nationwide was $55,100.16 Compared with the average salaries of other professionals who work full-time with college degrees, teacher salaries are shockingly low. In fact, teachers earn 60 percent of the average salaries of similarly educated full-time professionals—which is the lowest relative earnings among all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.17

Importantly, other nonwage benefits—pensions and summer break, for example—do not compensate for these lower salaries. An Economic Policy Institute analysis of weekly earnings found that adjusting for nonwage benefits only made up for a fraction of the wage difference between the salaries of the teacher workforce and other comparable professions.18 More specifically, in 2015, researchers found that the 17 percentage point gap in weekly earnings of elementary and secondary teachers and other comparably educated professionals was offset by 6 percentage points of no-wage benefits, for a remaining gap of 11 percent.19

As a result, throughout their careers, many teachers struggle to support themselves and their families.20 A CAP analysis found that mid-career teachers with 10 years of experience who serve as the primary breadwinner for their family of four may qualify for federally funded benefit programs designed for families in need of financial assistance.21 In some states, approximately 20 percent of teachers take a second job to supplement their salaries.22 Even in states with some of the highest teacher salaries, teachers struggle to find affordable housing, child care, and transportation options in cities with especially high costs of living.23 Indeed, a recent Education Resource Strategies study found that 30 states would need to increase teacher pay in order to bridge the gap between the state’s average teacher salary and a family living wage, with some gaps at or close to 18 percent.24

Unfortunately, teacher pay has worsened over time. After adjusting for inflation, average teacher pay has actually decreased over the past 40 years by just more than 1 percent.25 Moreover, from 2010 to 2016, the average teacher salary adjusted for the cost of living decreased in 39 states. In many of those states, the decrease was significant. In Mississippi, for example, the average teacher salary after adjusting for inflation dropped by slightly more than $9,000—from $61,270 in 2010 to $52,190 in 2016. Of the 12 states that had an increase in adjusted, average teacher salary, Vermont had the largest increase of just more than $4,000—$47,881 in 2010 and $52,264 in 2016. The 2016 salary is still lower than the average national teacher salary.26

The context for declining teacher pay is a larger pattern of disinvestment in public education since 2009. From 2009 to 2015, inflation-adjusted per-pupil spending decreased in more than 30 states.27 Not surprisingly, recent research shows that there is a strong correlation between per-pupil funding declines and a decline in teacher salaries. During this same time period, inflation-adjusted teacher salaries also declined in 40 states—and by 5 percent or more in 24 states.28

Finally, unlike in almost any other profession, 94 percent of teachers draw from their salary to purchase needed classroom supplies, sometimes items as basic as pencils and paper. A recent report from the National Center for Education Statistics found that the average teacher spent $479 on school supplies in the 2014-15 school year. Seven percent of teachers spent more than $1,000. Teachers in schools that participate in the free or reduced-price lunch program were more likely to spend their own money on school supplies.29

In order to recruit and retain strong teachers, particularly in schools with the greatest need, the teaching profession must offer similar financial benefits as other professions requiring the same level of education. In fact, researchers in the field of teacher quality and pay have noted that as the U.S. labor market has experienced gender desegregation, schools and districts that once had a static labor pool of college-educated women now must compete with other professions.30

The importance of teacher pay to attract and retain a strong, diverse teacher workforce

Increasing teacher pay has the potential to make teaching more attractive and entice effective, diverse candidates to enter and remain in the profession and thereby increase student outcomes.

Higher salaries will help attract and retain effective teachers

Research shows that teacher pay is a significant factor in an individual’s decision to enter and remain in the teaching profession. The national think tank Third Way surveyed current college students, and 89 percent of respondents reported that “salary for those established in the career,” not only starting salary, was an important factor in selecting a job.31 Many college graduates seek more lucrative job prospects than teaching.

Once in the classroom, salary is a factor in some teachers’ decisions to leave the profession. Increasing teacher salary is positively correlated with teacher retention. Studies in North Carolina; Tennessee; Texas; Florida; and Denver, Colorado, all show positive relationships between bonuses or salary increases and retention.32 This is important because years of experience is linked to greater teacher effectiveness. While teachers see the greatest increase in their effectiveness within the first five years in the classroom, teachers with more than 20 years of experience are more effective than teachers with five years of experience.33 But a 2015 longitudinal study by the federal government found that nationwide, 17 percent of teachers leave the profession within the first five years.34

Moreover, teacher turnover has a measurable negative impact on school stability, student achievement, and districts’ budgets.35 Further, turnover is highest in high-poverty schools, and underserved students are more likely to experience teacher turnover or churn.36 With greater churn, there is a continual rotating door of experienced teachers exiting the profession or leaving the school. Each of these moves is more likely to result in less-experienced teachers taking their place. A recent study found that high teacher turnover within a school not only affects the students in the classrooms with inexperienced teachers but also negatively influences schoolwide achievement levels.37 In other words, when a teacher quits, the entire student population absorbs the impact.

Recruiting, hiring, and training new teachers is time-consuming and costly for districts. In fact, the Learning Policy Institute estimates that urban districts spend more than $20,000 to replace a single teacher.38 Increasing the tenure of teachers’ service increases the return on districts’ investments in those teachers.39 Finding solutions to reduce turnover by addressing the reasons some teachers leave the profession will improve retention within the teacher workforce and increase student achievement. These solutions may also pay for themselves by freeing up dollars from new hiring efforts.

Relatedly, increases in teacher pay may not only reduce teacher turnover. Research shows that higher salaries also influence the quality of a districts’ applicant pool.40 A study in the San Francisco Unified School District found that an increase in pay can increase a school’s attractiveness in a local labor market—and by doing so increase the size and the quality of the applicant pool.41 After a salary increase, newly hired teachers in the district increased student gains for English language arts compared with cohorts of newly hired teachers in previous years.42 It is therefore reasonable to think that a long-term investment would have substantial, long-term impacts on both the size and quality of the applicant pool and the characteristics of teachers continuing to teach in a district with this type of pay increase.

Higher salaries will help diversify the teacher workforce

Research shows that earning potential influences the diversity of the teaching profession, and teachers of color contribute to increased student performance. Because teacher salaries are so low, student loan debt is a struggle for many teachers, and is among the specific obstacles that black and Latinx teacher candidates face to becoming teachers. Student loan debt is much higher for black students than for white students, and this debt—and the debt gap between black and white graduates generally—grows substantially over time.43

This is important given the positive impact of a diverse teacher workforce on student outcomes, as well as the large gaps remaining between the percentage of students of color and teachers of color across all school types.44 Studies show that having a teacher of color boosts math and reading achievement for students of color, as well as their graduation rates and college aspirations. Similarly, students of color experience less absenteeism and exclusionary discipline when taught by a teacher of color.45 And a recent study found that Black, Latino, and Asian students have more positive perceptions of black and Latino teachers across multiple facets of teaching than they do of white teachers.46

To the extent that this debt burden is an obstacle to increasing teacher diversity, increasing pay in these schools will likely contribute to the recruitment and retention of teachers of color—and in turn, positively affect student outcomes.

The impact of salaries in high-needs schools

Low teacher pay is an issue that affects the overall teacher workforce in most places, but it is especially problematic in high-poverty schools. Using data collected by the Department of Education in the Schools and Staffing Survey for the 2011-12 school year, the pay gap for beginning teachers in schools where 50 percent of students or more receive free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL) versus beginning teachers in schools where less than 50 percent of students receive FRPL is $200.47

However, the difference in average teacher salaries in high-poverty schools versus low-poverty schools is much larger. Based on 2015-16 school year data collected by the Department of Education via the National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS), there is a $4,100 gap between teachers working in the highest-poverty schools—where 75 percent of students or more receive FRPL—and the lowest-poverty schools—where 34 percent of students or less receive FRPL. This gap is likely largely driven by differences in overall district budgets,48 as well as differences in teacher experience and degrees across school types. High-poverty schools and school districts are stuck too easily in a repeating cycle of high turnover, less experience, and low average pay that repeats itself year after year.49

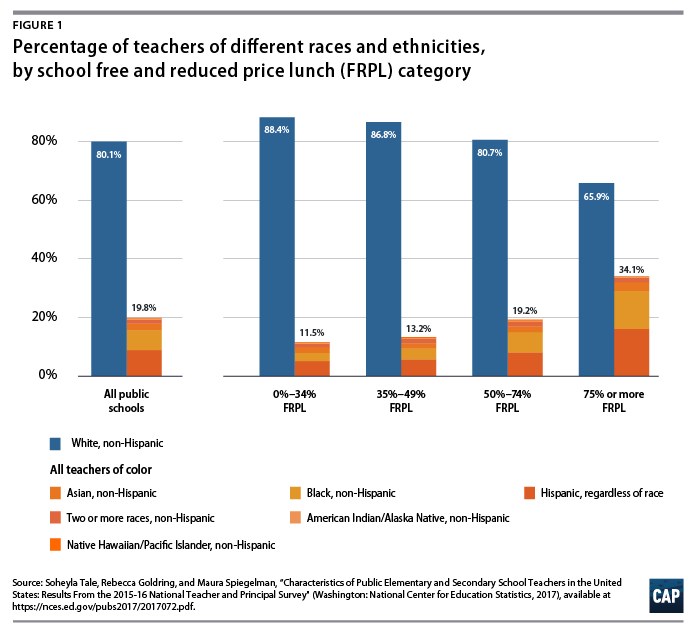

There are also important differences in average pay by teacher race and ethnicity. In part, these differences are likely due to unequal demographic distributions in high-poverty versus low-poverty schools. According to 2015-16 school year data,50 black teachers comprise slightly less than 3 percent of teachers in schools where 34 percent of students or less receive FRPL, but they comprise slightly less than 13 percent of teachers in schools where 75 percent or more students receive FRPL. Similarly, Hispanic teachers make up only 5 percent of the teacher workforce in schools where 34 percent of students or less receive FRPL, but they make up 16 percent of all teachers in schools where 75 percent of students or more receive FRPL.

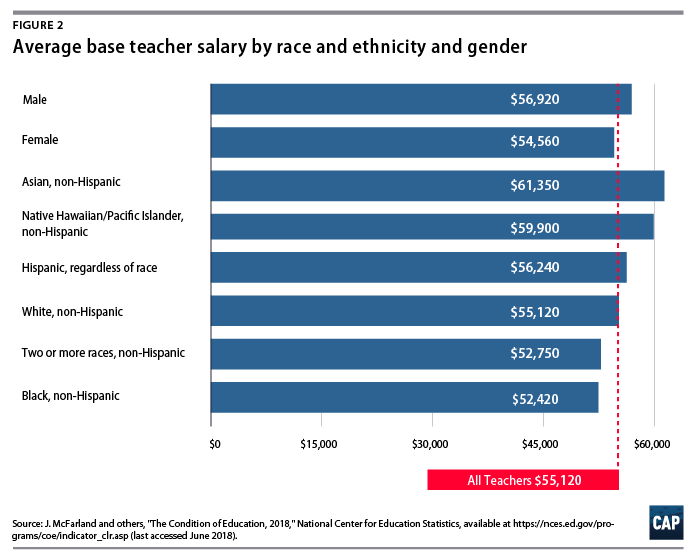

Indeed, while differences in pay are largely driven by experience and degrees, it is nonetheless important to note that on average, black teachers earn $2,700 less per year than white teachers. Further, the average salary of female teachers is more than $2,000 less than that of male teachers—$54,560 and $56,920, respectively.51 Importantly, recent research shows that even when controlling for degrees and experience, female teachers earn less than male teachers and black teachers are paid less than white teachers.52 Given these discrepancies, increasing pay for teachers in high-poverty schools has the potential to ameliorate concerning inequities in pay by race and ethnicity and gender in the teaching profession.

Need for federal action on teacher compensation

While a handful of districts have made strides in increasing teacher pay,53 average national salary has decreased over time after adjusting for inflation.54 States can and should do more to mediate funding inequities across districts—which are significant in almost half of states55—so that teachers in high-poverty schools see an increase in salary. While further investments are necessary to achieve meaningful increases in teacher salaries, it is unlikely that all states and districts will have the funding and capacity to implement systemic changes in the next few years, as they continue to navigate budget shortfalls.56 Additionally, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the legislation that has cut federal taxes, could have a devastating impact on states’ and districts’ ability to raise revenue through local taxes, thereby hindering the ability of states and districts to increase teacher compensation.57

A different approach is needed to meaningfully improve the teaching profession and thus student outcomes. Other high-performing countries pay teachers considerably more than the United States, and some of these have implemented a national strategy to increase teacher salaries.58 Singapore helps maintain adequate teacher salaries by certifying that they align with the compensation awarded to other similarly educated professionals.59 Faced with massive teacher shortages, the United Kingdom increased teacher pay, funded national recruitment efforts, and improved teachers’ working conditions.60 These international models have proven successful in addressing teacher quality—and by doing so, the quality of the education system.

While policymakers at the state and local levels must implement innovative strategies to boost teacher pay, the federal government should invest in high-poverty schools—the historical focus of federal education policy—in order to increase teacher pay.61

A federal tax credit for teachers in high-poverty schools

Like the governments of other high-performing countries, the U.S. government should act to protect and increase teacher compensation, especially for teachers in high-poverty schools. There is a precedent for federal investment in specific professions. For example, the federal government spends more than $15 billion annually on graduate medical education to support the development of the health workforce.62 Just as doctors are critically important to the health and well-being of the population, teachers are vital to the prosperity and well-being of the U.S. population.

To meaningfully increase pay for public teachers in high-poverty schools, the federal government should use the federal tax code to create a permanent $10,000 refundable federal Teacher Tax Credit, essentially serving as a wage boost. This would result in a significant increase in take-home pay—more than $190 per week. This would cover the average weekly cost of groceries for a family of four on a low-cost plan.63

According to Megan, this boost in pay would ensure that she could save for her son’s college and maintain savings for home repairs while still being able to afford to give her students the experiences and resources that are out of their reach. Megan said it pains her to send notes home to parents about field trips, knowing that they cannot afford to send their children when they cannot afford to put clothes on their children’s backs. Megan said she would use the extra money from the tax credit to provide her kids with experiences that they currently cannot get anywhere else.

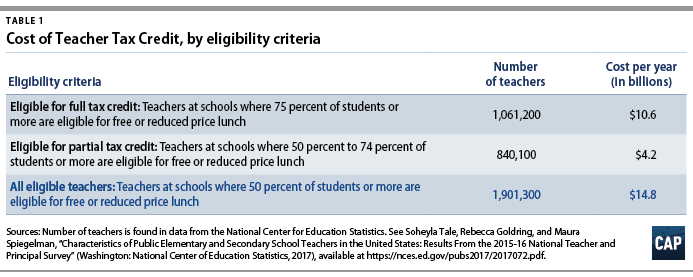

The full tax credit would be directed toward teachers in high-poverty schools—defined as schools where 75 percent of students or more receive free or reduced-priced lunch. The tax credit would then phase out as the percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch declines, in order to avoid a cliff effect where teachers completely lose the credit as soon as the number of FRPL students falls below the 75 percent threshold. The phase out will also address any unintended consequences caused by instability in FRPL rates across years. The value of the tax credit would decline by $400 for each percentage point, from 74 percent FRPL to 50 percent FRPL. So, for example, teachers in schools with 74 percent FRPL would receive a $9,600 tax credit.

Policymakers should also consider using a different FRPL threshold for high schools or schools with high immigrant populations, whose actual poverty rates may not be accurately reflected via FRPL statistics.64

The estimated proposal would cost about $15 billion annually, similar to the cost of the federal investment to supplement the cost to train doctors.65 The cost is also a drop in the bucket compared with the $1.5 trillion that the 2017 tax cut law will add to federal budget deficits over the next decade—an average of $150 billion per year in cuts that largely will be redistributed to the already wealthy.66

This investment would help attract more teacher candidates to high-poverty schools, as well as retain experienced educators in high-poverty schools. Investing in teachers in high-poverty schools helps teachers afford to teach in the schools with the greatest need and would increase the economic stability of teachers’ communities. It also sends the message to students in those schools that they are worthy and deserving of an experienced, well-paid, meaningfully supported teacher workforce. Ensuring that today’s students have high-quality teachers could change the trajectory of their lives and pave the way for a stronger future workforce.

The value of the tax credit—$10,000 per teacher per year—is set to close the gap between teacher salary and the average salary of all college graduates.67 A National Center for Education Statistics study also reinforces the need for this value, finding that a $20,000 pay increase over two years—meaning a boost of $10,000 per year for two years—successfully incentivized teachers in 10 different school districts to transfer to high-poverty schools and minimized turnover for those two years.68 The majority of research on the ability of financial incentives to redistribute teachers focuses on pay-for-performance or loan forgiveness policies—which are inherently different than this proposal, which increases base salary. This research shows that pay increases must be significant to influence teachers’ decisions and are most effective when coupled with policies to improve working conditions and increase teacher supports.69 Because this proposal is structured as a tax credit, all qualifying teachers would receive the full value of the tax benefit through a dollar-for-dollar reduction in the taxes they owe and a tax refund to the extent that the credit exceeds the taxes they owe.

The goal of supplementing the pay of those who teach in high-needs schools could be addressed through an explicit spending program administered exclusively by the U.S. Department of Education. But providing the supplement through the federal tax code has distinct and important advantages.

A federal tax credit is a simple, well-suited tool for supplementing the income of teachers in low-income schools. Indeed, increasing the pay of teachers serving in high-needs schools should be a national priority, but state and local policymakers alone cannot address this issue uniformly. Thus, increasing pay for teachers in high-needs schools through the federal tax code is a fundamental step toward the national goal of reducing poverty and boosting the economy.

Increasing teacher salaries through a permanent tax credit would also provide certainty to qualifying teachers in a way that an explicit federal spending program may not. Unlike a discretionary federal spending program, the tax credit would not be subject to annual appropriation negotiations. Instead, teachers could count on the availability of the additional boost in pay. While mandatary spending programs are also not included in annual appropriation negotiations, they are highly unusual in federal education programs.70 The largest spending programs in elementary and secondary education that also provide critical support to states, districts, schools, and students—Title I of the Every Student Succeeds Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act State Grants—are all discretionary.71

Because a tax credit would be stable, it could be a real and significant factor influencing teachers’ long-term decisions about whether and where to teach. States and districts would have an incentive to include the information about this tax credit in their recruitment materials to increase the number of applicants to high-poverty schools, which are likely to have greater turnover and less experienced teachers.

A tax credit also would complement existing federal policy that supplements state and local dollars to improve instruction for students enrolled in high-needs schools. Title I of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) provides schools with additional funding to serve students from low-income families.72 Schools with at least 40 percent of students in poverty may spend the additional dollars to improve their overall education program, including hiring additional teachers or guidance counselors to provide supplemental services or to reduce class sizes.73 The tax credit would increase the compensation of the teacher positions in high-poverty schools in the local labor market.

While CAP believes that a new federal investment is necessary to dramatically improve teacher pay, other efforts at the federal, state, and local levels are essential to maximize compensation for all teachers. This proposal is intended to operate in tandem with existing policies to increase teacher pay—and should not replace or supplant existing policies. Because the tax credit will increase pay differently within districts and salary schedules are set districtwide for the vast majority of teachers, states and districts will not be able to use this proposal to supplant other initiatives to increase teacher pay. Federal legislation should also provide protections to ensure that states and districts maintain and increase their investment in teacher salaries. This may include an assurance that districts with teachers eligible for this tax credit do not lower salaries, public reporting of teacher salary, and descriptions for how states plan to leverage the Teacher Tax Credit to improve instruction in high-poverty schools.

In addition to the tax proposal, the federal government should maintain current provisions to boost take-home pay, including through teacher loan forgiveness programs and the educator expense deduction.74 States should also increase funding for teacher pay, especially targeting additional funding at the districts with the greatest need. As a vehicle to drive this change, states should take advantage of the weighted student funding pilot in ESSA.75

Districts should also increase funding and resources dedicated to teacher compensation. Some of these policies—all of which should be developed in coordination with the local teachers union—may include developing career ladders,76 implementing policies to reduce teacher turnover,77 and improving loan forgiveness programs.78 Districts may also consider providing teachers with the opportunity to extend the number of weeks they work during a school year as a way to further increase income, on top of a boost in base pay to bring the teaching profession more in line with other professions, such as those in the medical and legal fields.79

Moreover, research shows that working conditions and teacher supports are also critical to attracting and retaining teachers. Given this, it is critical that federal, state, and local policies address challenges to working conditions and implement policies to modernize the teaching profession.80

Conclusion

Teachers earn far less than other professionals with similar levels of education, and the impact of this wage gap is far-reaching: Teachers struggle to provide for their families; the profession loses top talent to higher-paying careers; and students, especially those in high-poverty schools, experience high teacher turnover. Taken together, these consequences have a negative effect on the strength, stability, and diversity of a critical portion of today’s workforce and will influence the life outcomes of tomorrow’s. Certainly, salary considerations and working conditions influence teachers’ decisions on whether to leave the classroom, and policymakers should implement policies that modernize the teaching profession across the entire teacher pipeline.

Other high-performing countries have implemented systemic changes to increase teacher pay, recognizing its interconnectedness to improving teacher quality, recruiting a diverse teacher workforce, improving student outcomes, and promoting economic and cultural prosperity. A similar response is needed in the United States.

This report demonstrates that an increase in pay for teachers in high-needs schools will lessen pay inequities, reduce teacher turnover, and support efforts to increase teacher diversity—and by doing so, will increase overall student achievement. This investment in the teacher workforce will also increase teachers’ earning potential and help rebuild a prosperous middle class. The federal government should take action to boost the pay of teachers in public elementary and secondary schools, especially for teachers such as Megan who work in high-poverty schools and too often must choose between caring for themselves and caring for their students.

About the authors

Meg Benner is a senior consultant at the Center for American Progress. Previously, she was a senior director at Leadership for Educational Equity. Benner worked on Capitol Hill as an education policy adviser for the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, where she advised former Ranking Member George Miller (D-CA) and served as a legislative assistant for Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and former Sen. Christopher Dodd (D-CT). She received her undergraduate degree in American studies from Georgetown University and a master’s degree of science in teaching from Pace University.

Erin Roth is a senior policy analyst for education innovation at the Center. Previously, Roth served as the early childhood education research alliance lead at the American Institutes for Research, which supports education policy and research needs in seven Midwestern states through the Regional Educational Laboratory Midwest—funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences. Roth received her bachelor’s degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a master’s degree in sociology of education, education policy from New York University.

Stephenie Johnson is a senior consultant and formerly the associate campaign director of K-12 Education at the Center. In this capacity, she researches, develops, and writes policy recommendations aimed at elevating the teaching profession. Before coming to the Center, Johnson completed the Social Policy & Politics fellowship at Third Way, a think tank in Washington, D.C. She is also a former fifth-grade teacher. Johnson earned her J.D. and M.Ed. from Boston College and her B.A. in political science from Rhodes College.

Kate Bahn is an economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Her areas of research include gender, race, and ethnicity in the labor market, care work, and monopsonistic labor markets. Previously, she was an economist at the Center for American Progress. Bahn also serves as the executive vice president and secretary for the International Association for Feminist Economics. She has published popular economics writing for a variety of publications, including The Guardian, The Nation, Salon, and Newsweek. She received her doctorate in economics from the New School for Social Research and her bachelor of arts from Hampshire College.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge several people who helped with this report. Catherine Brown, vice president of Education Policy at the Center for American Progress, helped develop the idea and provided invaluable feedback throughout the process. Lisette Partelow, director of K-12 Strategic Initiatives at the Center, helped structure the report. Alex Thornton, senior director of Tax Policy, provided critical feedback on the structure of the tax credit. We appreciate Megan Doerr’s willingness to let CAP tell her story. Thanks to peer reviewers for their feedback to strengthen the narrative and recommendation, including: Megan Allen, director of Partnerships at the National Network of State Teachers of the Year; Katherine Bassett, former president and CEO of the National Network of State Teachers of the Year; Ninive Calegari, CEO and founder of the Teacher Salary Project; Jessica Cardichon, director of Federal Policy at the Learning Policy Institute; Simone Hardeman-Jones, national director of Policy at Partnerships at Educators for Excellence; Tamara Hiler, deputy director of education at Third Way; Eric Isselhardt, senior executive at the National Network of State Teachers of the Year; Bethany Little; principal at EducationCounsel; Mildred Otero, vice president of Policy and Advocacy at Leadership for Educational Equity; Melissa Tooley, director of PreK-12 Educator Quality at New America, and Vanessa Williamson, a fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution. The authors would also like to thank Sean Corcoran, associate professor of economics and education policy at New York University (NYU) Steinhardt, affiliated faculty of the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, and associate director of NYU’s Institute for Education and Social Policy, as well as Dorothy Jean Cratty, an independent consultant who reviewed the original analysis and strengthened the framing and interpretation of the conclusions.