The issues of press freedom and freedom of expression in Turkey have for several years attracted a great deal of attention and provoked extensive debate both in Turkey and in other Western countries. Dozens of journalists critical of the government have been jailed, and hefty fines have been levied against media outlets seen as opposing the ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP. The perceived deterioration of the situation has raised concerns about the course and character of Turkish democratic development.

This brief provides political context, historical background, and strategic analysis of this problem, and offers steps that the United States can take to help address the situation. The intention is to broaden the discussion and improve understanding of the issue among a wider audience, particularly in Washington, D.C., in the hopes of encouraging greater U.S. engagement. What follows is based on secondary research, extensive interviews with Turkish journalists, editors, and outside experts, and working-group meetings in Istanbul and Washington, bringing together prominent Turkish journalists and U.S. and European experts.

Our goal is not to provide an exhaustive exploration of the current state of press or media freedom in Turkey, nor is it to provide new data on the exact number of jailed journalists or the character of their alleged crimes. There are a number of informative reports that provide those details and include insights on the current state of press freedom in Turkey. Marc Pierini, a former EU ambassador to Turkey, has perhaps the most up-to-date and balanced study. The Committee to Protect Journalists plays an important role in tracking the exact number of jailed journalists, monitoring their legal status, and advocating on their behalf; their website and recent reports have detailed breakdowns of these issues. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the U.S. Department of State both exhaustively track the trials of journalists and evaluate the broader human-rights environment in Turkey, and their periodic reports contain a wealth of information.

By understanding the historical sensitivities feeding the current political crisis in Turkey, outlining the suppression of certain forms of political discourse, and examining the issue in the context of U.S. engagement with Turkey and the wider region, a new picture emerges. The United States wants Turkey to be a capable and secure democratic partner with whom it can engage the broader Middle East, and therefore it should more clearly voice its concerns about the deterioration of press freedom and freedom of expression in the domestic political context. Given the wave of popular mobilization in the region and the careful negotiations between the Turkish government and Kurdish separatists, it is more important than ever to preserve the democratic nature of the “Turkish model,” which we discuss in more detail below.

Historical context

To understand the current political situation and the importance of reinforcing democratic principles over the coming years, it is necessary to provide some historical context of press freedom and freedom of expression in Turkey.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, journalists were targeted and sometimes killed by actors ranging from ultranationalists to Islamists, far leftists to the Kurdish Workers’ Party, or PKK, who seek Kurdish autonomy and greater legal and cultural protections. Current Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s AKP has successfully defused much of the violence that characterized the extreme polarization of Turkish society in those years since coming to power in 2003. But the 2007 murder of Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, shot outside his newspaper’s offices in Istanbul for advocating official recognition of the Armenian genocide, served as a reminder that the violence underlying political tensions and freedom of expression in Turkey has not disappeared.

The Kurdish issue

The “Kurdish issue,” as it is delicately referred to in Turkey, is one major historical legacy shaping the current political environment and affecting press freedom. Approximately 15 million Kurds—an ethnic and linguistic minority inhabiting parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran—live in Turkey today, with the vast majority being fully integrated into Turkish society and many living in major urban centers, particularly Istanbul.

Despite widespread acceptance of Kurds and their integration with broader Turkish society, for decades the ultranationalist Turkish state attempted to suppress Kurdish cultural and linguistic diversity, banning, for example, the use of the Kurdish language until 1991. The remnants of this repression remain visible, as the politics surrounding the Kurdish language and culture are still hotly debated, particularly in the heavily Kurdish southeast, and nationalists continue to use fears of Kurdish autonomy to appeal politically to older Turks raised on strict Kemalist doctrine. The PKK, a far-left guerilla group labeled a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union, has also exploited these fears to continue their decades-long struggle for Kurdish independence and autonomy. More than 40,000 people have died in this fight since the 1980s. Several peace initiatives have been introduced and failed over the past decade, and violence, while down from its peak in the mid-1990s, has continued.

The AKP has worked to address some of the cultural concerns of the Kurdish minority, allowing the use of Kurdish language and permitting peaceful Kurdish political mobilization. Nonetheless, most Turks have been educated in highly nationalist curriculums and remember the violence of the PKK movement, and are thus deeply wary of any hint of separatism. This has led to pressure on the AKP to continue security operations against the PKK and to avoid concessions to the Kurds. The extreme sensitivity of the Kurdish issue in Turkish politics means it bleeds into areas such as freedom of the press. Many reporters or editors reporting on PKK activities or discussing Kurdish cultural or political activities have faced censorship, arrest, threats, or outright violence.

In this context, shaping a lasting and peaceful solution to the Kurdish issue has proved difficult. The past six months have seen considerable progress, however: A ceasefire negotiated between the government and Abdullah Ӧcalan, the PKK’s jailed leader, has led to a wider peace initiative and the best chance for a settlement since the conflict began.

Since the AKP’s electoral success in 2002, the country has seen a remarkable period of economic growth, political reform, and relative stability. This has given the party the chance to institutionalize the changes it has brought to the Turkish state such as greater legal and cultural recognition of Kurdish and Armenian minorities. The party was formed as a broad alliance of religious conservative parties that were previously banned under Turkey’s secular constitution, members of the newly emergent Anatolian middle class, social conservatives, and liberal elements that were frustrated with the incumbent Republican People’s Party, or CHP.

Electoral success and economic growth has also made Prime Minister Erdoğan one of the most influential leaders in the Middle East. This clout was visible during his tour of the Arab world following the upheavals of 2011—he was greeted by cheering throngs at nearly every step. His and Turkey’s popularity increased talk of a “Turkish model” of democratic development, secular government compatible with Islamic conservatism, and economic growth. The Turkish model means many things to many people throughout the region but is undoubtedly one narrative open to moderates seeking to shape new political cultures in the wake of the Arab Spring.

The AKP’s rise to power was a manifestation of trends that began in the 1980s, when center-right Prime Minister Turgut Özal—later president from 1989 to 1993—oversaw the opening of new economic markets and the modernization of the Turkish economy. This process had unintended consequences for the country’s established elites—the far-right Nationalist Action Party, civilian administrators, powerful Istanbul oligarchs, and influential military leadership—who had long benefited from the strong state and military apparatus built by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The macroeconomic conditions, liberalization of the Turkish economy resulting from Özal’s reforms, and deepening trade ties to the Middle East all contributed to rapid urban growth in Anatolia and the rise of an Anatolian business class, which would become a crucial constituency for the AKP. By 2011, when Erdoğan’s AKP secured 50 percent of the popular vote, more than 20 cities in central and eastern Turkey were each generating more than $1 billion of trade.

The emergence of these new centers of economic power in Anatolia over the past two decades has had profound political repercussions. Many among the new Anatolian business classes resented the clientelist nature of the Kemalist elite, centered on patronage and loyalty to statist doctrine, and came to closely associate with the political coalition behind the AKP’s rise and electoral success. The more virulently nationalist elements of the Kemalist camp only contributed to these suspicions and resentments by attempting to stifle dissent and freedom of expression by outlawing Islamist political parties and banning symbols of cultural or religious diversity such as the headscarf or the Kurdish language.

The Kemalist old guard could claim the mantle of constitutional legitimacy for much of this process, defending the constitution that is still in place today—written under military rule in the early 1980s—which limits cultural and political liberties, requires the country to be governed “loyal to the nationalism of Atatürk,” and assures the military considerable political influence. Despite this veneer of legitimacy, democratic principles were repeatedly ignored through this process. In 1997, for example, the military forced out the government of the AKP-predecessor Welfare Party in the so-called post-modern coup, arguing that the religious conservative movement had become a threat to Turkish security. Prime Minister Erdoğan himself, then the mayor of Istanbul, was imprisoned for a short time in 1998 for reciting a poem protesting the ban of the Welfare Party, which authorities deemed was inciting religious hatred.

Despite these hurdles, the reconstituted and modernized religious-conservative-reform movement, now under the umbrella of the AKP, managed to win a large majority in parliament in 2002, due in part to widespread anger at official corruption and the state of the economy. Given the historical fear of the Turkish deep state—the conspiratorial statist and corporatist elements that many Turks still believe run the military and intelligence apparatuses—the legacy of repeated military coups, and the recent memory of the 1997 military intervention and subsequent banning of the Welfare Party, it is unsurprising that upon gaining power in 2002 the AKP moved quickly to curb the influence of the military and other branches of the Kemalist establishment that it felt hindered the burgeoning democracy and threatened the party. The party’s reforms, accomplished over many years, included abolishing the military courts that had been influential in stifling dissent, loosening restrictions on the press and religious or cultural expression, asserting civilian authority over military commanders, and pushing to rewrite the constitution.

The AKP’s democratic initiatives had a number of positive outcomes. First, because the religious-conservative movement had been stifled through many of the same tools that the security apparatus used to repress Turkey’s Kurdish minority, the AKP broke down many of the taboos that had surrounded discussion of the Kurdish issue. Second, real progress was made on the longstanding Turkish intentions to join the European Union. The AKP frequently turned to the European Court of Human Rights and made significant progress implementing the reforms needed for EU membership, often using the EU accession process as a way to counter the influence of the old elite, particularly within the judiciary. Finally, in part because the AKP’s electoral victory was such a watershed event in Turkish political history, and in part because the party had so recently experienced censorship and repression, the AKP accession prompted a profound opening of the Turkish political debate. From 2002 to 2009 numerous topics of discussion that had previously been banned from public discourse—such as the status of the Kurdish minority, Turkey’s history with Armenia, and the role of the military in politics—were openly and vigorously debated in parliament.

The AKP’s consolidation of civilian control and its breaking down of religious and cultural taboos was deeply disruptive and threatening to many of the elite Turks raised on the strict Kemalist doctrine of secularism, statism, and military prestige. This shaped a situation of mutual paranoia, wherein all sides of the political debate harbored deep suspicions regarding the motives of their opponents, and longstanding grudges—often intensely personal—animated many political actions.

This mutual suspicion is still strong in Turkey today. Kemalists and many secular Turks express fear of a creeping Islamist takeover or concern about conservative religious groups’ presence in the police forces and the judiciary. Meanwhile, fears of the deep state and mistrust of the military remain powerful among AKP circles, despite considerable improvements in civilian control of the military. It is in this context that concerns have grown that the cycle through which the AKP oversaw a necessary retrenchment of the Kemalist security apparatus has gone too far, and that the AKP has begun to assume some of the repressive characteristics of the regime in whose shadow it was originally formed. Against this backdrop, and because so much of the AKP’s coalition was formed around a critique of illegitimate use of power, Prime Minister Erdoğan’s increasingly aggressive responses to criticism from the press is especially troubling.

Strategic concerns trump democratization issues

Strategic concerns have dominated policy discussions of Turkey in Washington, D.C., for several years. President Barack Obama’s administration has worked hard since 2009 to renew ties with Turkey and cultivate Prime Minister Erdoğan’s AKP as an important partner and interlocutor in the region. As such, U.S. officials and policy analysts focused on defining a cooperative regional agenda, improving security ties, widening economic access, and working to resolve the longstanding Kurdish issue. Questions surrounding Turkey’s ongoing democratization, including issues of press freedom and freedom of expression, were therefore often sidelined.

The diplomatic thinking was sound in 2009—Turkey was, and is, a NATO ally, a democracy, an important regional military power, and a fast-growing economy with increasing ties to the Levant. The relationship between the two nations had deteriorated during the George W. Bush administration and needed renewal. Turkey had held successive free and fair elections for nearly a decade, overseen important economic reforms, made important and highly symbolic concessions to its Kurdish minority, and was beginning the process of rewriting and updating its constitution. Additionally, due to economic ties and the Kurdish population in the southeast region of the country, Turkey was likely to play an important role in shaping the future of Iraq after the American withdrawal. The possibility of escalating tensions with Iran regarding its nuclear program also loomed on the horizon. Despite being a close U.S. ally and regional counterweight to Iran, Turkey is dependent on Iranian energy resources and therefore crucial to any tightening of sanctions on Tehran to complement the Obama administration’s diplomatic efforts.

For all of these reasons, the Obama administration placed strategic concerns at the heart of the U.S.-Turkish bilateral relationship. The United States did not explicitly sideline issues of democratization, but these issues were superseded by more pressing concerns. This strategic focus was lent further urgency by the political upheavals that swept the region in 2010 and 2011 and by the continuing violence in Syria, which left the United States searching for stable allies in the region.

As a result, issues of democratic reform lost significance for many in the policymaking establishment. Prime Minister Erdoğan’s repeated electoral victories—increasing the AKP’s share of the vote in both 2007 and 2011—and his growing personal dominance of Turkish politics elicited concern from civil-society activists, who worried about his rigidity in response to criticism, but officials in Washington and Ankara largely relegated such concerns to second-tier status.

The sidelining of press freedom, minority rights, and judicial reform now threatens to impact the joint strategic project being advanced by the United States and Turkey to establish secure and democratic governance in the region and foster economic growth. The fact that Turkey has regressed on issues of press freedom and stalled on judicial reforms undermines the persuasive power of the Turkish democratic model in the wider region. In a parliamentary system, public opinion is an important check on political power. The legitimacy of elected governments is tied to the free exchange of opinions, ideas, and criticism—this is how the public compels political authorities to remain accountable on a daily basis. If Prime Minister Erdoğan and the AKP are serious about overcoming Turkey’s undemocratic traditions, then maintaining and deepening freedom of expression and permitting dissenting voices in the public sphere is critical.

Given the turmoil in the region, with many nascent political movements searching to define their future paths, Turkey cannot afford to come across as undemocratic or as cracking down on freedom of expression. The issue of press freedom is at the core of Turkey’s development as a modern democracy. Vigorous—and often controversial—internal debate is necessary to help reinforce Turkish leadership in the region and the strategic partnership with the United States.

A key juncture in Turkish politics

The next two years will be tremendously important in directing the next phase of Turkish democracy, with the rewriting of the constitution, the proposed shift to a system embracing a strong presidency, the ongoing reform of the judiciary, and continuing outreach to PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan and negotiations with field elements of the PKK all currently underway. Each of these processes requires a strong and vigilant press to voice criticism and provide oversight, meaning it is crucial that the freedom of the press be protected.

The role of the press is lent further importance by the current lack of serious political opposition to the AKP. The primary opposition party—the CHP—is still undergoing a long-term reshuffling to widen its appeal beyond the urban elites and remove some of the old guard, who have so closely associated the party with the excesses of the old Kemalist structure. The extended period of AKP dominance has allowed it to consolidate control of the courts and weaken the military’s political influence. But this consolidation, even if necessary or natural after a decade of rule, has left the press as the only government oversight body and as such has perhaps helped make it a target for the AKP, which has developed an increasingly confrontational relationship with critical journalists and news outlets.

The stalled EU accession process has also played a role in establishing this dynamic. Throughout the early 2000s, this process had incentivized Turkey to undertake important reforms and protect democratic processes, but the European Union’s economic hardships and the wariness of many European politicians to support Turkey’s bid have together made accession a less-enticing prospect than it was for much of the past decade. This has meant that progress on meeting the EU membership requirements has slowed and that criticism from the European Union, which had previously been influential in pushing Turkish reforms, is increasingly ignored. Given the United States’ relative silence on press freedom in Turkey and clear prioritization of other issues in the region, there are few outside voices holding the AKP accountable.

Political journalism in Turkey

The issues outlined above have led the Turkish administration to assert increasing control over the political debate in the country and have led to meaningful lapses in democratic governance. Prime Minister Erdoğan wants to be remembered as a transformative leader who established legitimate democratic governance—the bookend to Atatürk himself in modern Turkish history—and intends to establish a presidential system wherein he can continue to govern after term limits end his time as prime minister in 2015.

Despite these goals and his record of accomplishments since 2002, Prime Minister Erdoğan has come to view any criticism of his government as a personal attack. Despite the measured reforms and removal of many taboos, Turkish political culture and journalism are both intensely personal. For many in Turkey, political disagreements end with participants debating a person rather than an idea and engaging in ad hominem attacks. Sometimes provoked by journalists’ vitriolic attacks, politicians—including the prime minister himself—often mention critics by name in print or in speeches, which can lead to threats or intimidation from unscrupulous supporters. The prime minister has also filed five libel suits against journalists for personal attacks since 2005. While some of the criticism for which Prime Minister Erdoğan has sued is distasteful—depictions of the prime minister as an animal, for example—the political power of his office is such that these lawsuits have a chilling effect on legitimate political debate. Given his overwhelming political power, Prime Minister Erdoğan would do better to rise above such slights and work to cement a new precedent for political leadership.

So far, the government’s behavior has tended toward greater repression. But a disclaimer is necessary before delving into the details of the imprisonment of journalists and media ownership, as well as direct and indirect censorship in Turkey. While these are very serious concerns demanding attention and resolution, comparisons of Turkey to authoritarian countries such as Iran, China, or North Korea are off base. Some organizations monitoring the situation in Turkey have drawn such comparisons in order to attract attention to the plight of imprisoned journalists, and while their motives may be good, such overreach undermines the wider political effort to ensure reform, as it provides the government with the opportunity to dismiss all outside criticism as overhyped. Turkey today is more democratic than in the past, if perhaps less socially liberal. The country has, in many ways, a healthy civil society, enshrined civilian authority, and a vibrant political debate. While there is still work to be done, we should not dismiss how far the country has come since the “post-modern” coup of 1997.

Jailed journalists

As of the end of 2012, Turkey had imprisoned at least 49 journalists for their reporting—more than any other country in the world. As Joel Simon, executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, has written, “Turkey has no business being the world’s leading jailer of journalists.” Turkish civil society is vibrant; its television shows are enjoyed throughout the Middle East. And the AKP has grown its share of the popular vote in three successive, legitimate national elections. What reasonable explanation could there be for such widespread imprisonment of journalists?

A study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace shows that the jailing of journalists is linked to the lack of a resolution of two larger issues: the ongoing Kurdish unrest and the role of the military in Turkish politics. Of course, those two issues are in turn associated with the judicial-reform process and the drafting of a new constitution to replace problematic remnants of the military constitution that still governs the country. The existing constitution’s broadly defined laws governing national security and territorial integrity provide ample room for abuse by overzealous prosecutors, while the twin fears of the military deep state and Kurdish separatism lead to prosecutions of those who may be engaged in legitimate reporting or political advocacy.

The majority of imprisoned journalists are Kurds charged under the remit of Article 314 of the Turkish Criminal Code or under the Turkish Anti-Terror Law. According to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s most recent study of the issue in August 2012, 68 percent of Turkish journalists in prison were jailed on charges related to the Kurdish issue; 13 percent were related to the ongoing Ergenekon trial of alleged right-wing coup plotters; and 19 percent were jailed on assorted other charges.

Both Article 314 of the Turkish Criminal Code and the Turkish Anti-Terror Law are overly broad and poorly defined, leaving them open to abuse by prosecutors and judges for a wide array of reasons. The Turkish Anti-Terror Law, for example, declares it a crime to “print or publish declarations or announcements of terrorist organisations.” The law is intended to target those dispensing terrorist propaganda but leaves open the possibility of prosecution for any number of journalists trying to cover the activities of the PKK or other terrorist groups. The Anti-Terror Law also deems anyone a terrorist if he or she is a member of an “organisation with the aim of changing the attributes of the Republic as specified in the Constitution, the political, legal, social, secular or economic system.” Of course, the current constitution was written under military rule, and any number of legitimate political actors want to “change the attributes of the Republic as specified in the Constitution,” making this a particularly problematic clause for a modern democracy.

Turkish government officials are quick to point out that some of the imprisoned journalists were probably members of the PKK, labeled a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union. Equally, there are journalists imprisoned who are clearly not members of the PKK or even advocating on the organization’s behalf. Even delving into the details of individual cases, it is very difficult to know the truth, and therein lies another central problem—the lack of transparency surrounding the process. Government sources claim that a number of jailed journalists were in fact engaged in illegal activities, while the Committee to Protect Journalists found that there was not sufficient evidence to determine guilt, according to their investigation. The fact that this is a matter of debate between government officials and their supporters and a nongovernmental organization is in itself a condemnation of the lack of transparency and due process under the law when it comes to prosecuting journalists.

The abuse of the Anti-Terror Law’s broad provisions has provoked criticism from the U.S. Department of State, the European Commission, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The Turkish government has every right to defend Turkish citizens, the state, and its territorial integrity and to prosecute terrorists. The impasse, however, is rooted in what has been, until recently, a mostly military approach to the Kurdish issue. The criticism comes about because of the frequency with which prosecutions tend to target those who could claim to be merely reporting on PKK activities, a reasonable journalistic pursuit, while not being members of the group themselves. As Marc Pierini, former EU ambassador to Turkey, has written, the “judicial system tends to blur the line between the intention to incite, praise, legitimize, or relativize terrorist violence and the expression of an alternative, critical, or even disturbing opinion.”

The solution to the issue of imprisoned journalists certainly lies in the dual need for a new constitution and judicial reform. A new constitution could eliminate the legal loopholes that allow for the prosecution of political opponents under overly broad legal justifications. The other issues linked to imprisonment are largely a result of badly needed judicial reform and proper due process. Many journalists are charged and then held in prison for extremely long periods of pretrial detention, and their release on bail is uneven and unpredictable. Defendants and their lawyers repeatedly complain of a lack of access to evidence, while those trying to monitor the trials are foiled by the utter lack of overall transparency. A new constitution could also contribute to the permanent peaceful resolution of the Kurdish issue through constitutional protections for minority rights.

It is time for Turkey to truly embrace the role of a confident democracy by allowing the open debate of these issues, particularly the Kurdish question. The AKP is the dominant force in Turkish politics, enjoying electoral legitimacy and broad popularity, and therefore should be encouraging such discourse rather than stifling it through the shadowy use of outdated security laws or judicial malpractice.

Media ownership

Turkey’s crisis of press freedom extends beyond the outright silencing of journalists through imprisonment. The government and its allies have also utilized more subtle forms of pressure in recent years. Much of the problem stems from the consolidation of major media holdings over the past two decades and the cross-ownership of media outlets by large conglomerates. The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, the European Commission’s 2012 Progress Report, and the U.S. State Department’s Human Rights Report have all identified the cross-ownership of media outlets as a threat to freedom of the press in Turkey.

This cross-ownership of media entities—wherein large conglomerates with major economic interests in other sectors such as construction or energy control media outlets—can open up reporters, editors, and owners to a variety of pressures. Companies with interests across economic sectors often rely on government contracts or regulation, leading to situations where they are asked or decide to apply pressure to limit political criticism, which could jeopardize those interests or contracts. While smaller companies are not as influenced by potential pressure on wider business interests, big conglomerates are under tremendous pressure. Numerous Turkish journalists cited instances where they were told to tone down government criticism or had columns pulled because of such concerns. This pressure manifests itself in direct pressure on news-outlet owners from government officials and more subtle forms of self-censorship from editors and journalists afraid of dismissal.

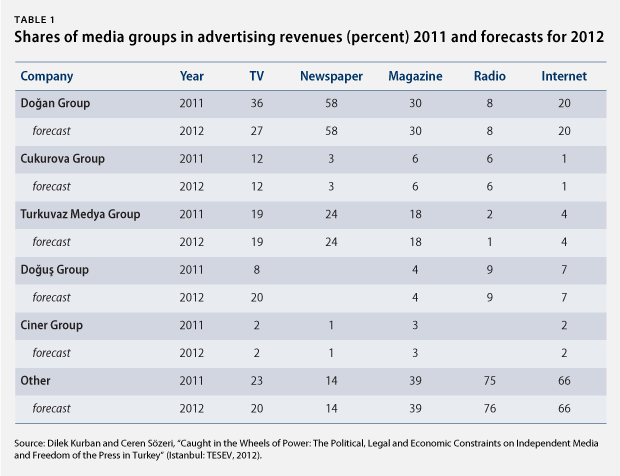

The independent think tank Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation, or TESEV, has documented that the Turkish media market came to be dominated by several cross-sector companies through a series of mergers following the end of the state monopoly over broadcasting in the 1990s. As can be seen from the table above, this consolidation of holdings has led several companies to dominate the Turkish media scene, across different mediums.

The case of Doğan Group illustrates this point most clearly. In 2009 the Turkish authorities levied a $2.5 billion fine against Doğan Group, then the largest media company in Turkey, for unpaid taxes. The fine was widely viewed as a political move to punish Doğan for its media outlets’ negative coverage of the AKP and Prime Minister Erdoğan. For weeks before the fine was announced, Prime Minister Erdoğan spoke publicly against the opposition press, telling his supporters at rallies, “Don’t buy these newspapers, they are full of filth and lies,” adding that audiences should “sentence them to poverty.” Such language, besides being inappropriate for the office of prime minister, tends to undermine the tax authorities’ claims to an unbiased assessment of the Doğan Group’s alleged financial improprieties.

Multiple sources in Turkey described the fine against the Doğan Group as having a “chilling effect” on journalists, editors, and media owners. For some Turks, particularly those in the opposition media, the Doğan fine was the highest-profile incident in what seems to be a trend of tax or bankruptcy proceedings intended to silence opponents in the press. Skeptics point to the uncontested auction of the ATV-Sabah media group in 2008, when the company held large shares of both print and television markets, by the Turkish Savings Deposit Insurance Fund, or TMSF, to allies of Prime Minister Erdoğan, including his son-in-law and brother, following bankruptcy proceedings as a point of concern. The uncontested state auction of a large media company to a close ally of Prime Minister Erdoğan stoked fears that the prime minister was seeking to assume informal control of the media.

More systematic concerns exist as well, surrounding the leasing of broadcast frequencies, issuance of journalist credentials, and the problematic Media Law, which states that television broadcasters must lease their frequencies from the government, as stipulated in Article 26 of the constitution, because they are regarded as finite resources, meaning the rights can also be revoked by regulators at the Radio and Television Supreme Council, or RTÜK. For journalists critical of the government, obtaining press credentials can also become an issue; the government periodically denies credentials to opposition newspapers. Finally, under current law the government can prosecute and fine media outlets and journalists, for example, for ill-defined offenses linked to national security, decency standards, and libel. As with the terrorism laws, such poorly defined legal standards open the door to abuse and political prosecutions.

More subtle censorship

Faced with this array of pressures, many journalists and editors practice varied forms of self-censorship. Because of the examples made of critics through outright prosecution, fines, or public mention by the prime minister or other officials, many conclude that it’s not worth the risk to explore sensitive issues such as the PKK or the Ergenekon trial. Several sources in Turkey reported receiving death threats in the wake of public criticism of the government or in response to particularly controversial columns on traditional political taboos such as discussion of Kurdish political activities or the death of more than 1 million Armenians during and after the First World War.

Journalists and editors also report pressure on content from owners, leading to fears of dismissal. Indeed, there are countless instances of columnists or journalists being dismissed for refusing to tone down criticism or for breaking controversial stories. Most recently, veteran journalist Hasan Cemal was dismissed from Milliyet newspaper for defending the publication of minutes from a meeting between representatives of the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party, or BDP, and the PKK leader Abdullah Ӧcalan. The leaked minutes provided fodder for nationalist critics of the peace process, angering Prime Minister Erdoğan, who publicly criticized Milliyet and condemned Cemal’s column on the subject, declaring, “If this is journalism, down with it!” Such public condemnation from a sitting prime minister brought tremendous pressure to bear on Milliyet’s owner, who refused to publish a subsequent column and then fired Cemal.

The concerns of critics and outside observers should not shroud the fact that many owners, editors, and journalists are quite happy to self-censor or cooperate with the authorities. The motivations for this cooperation can vary from political proximity and personal ties, to business interests and a desire for access to information, to a genuine yearning for unity on issues of national security. The blame for such censorship does not lie squarely with the government but also has its roots in the varying quality of journalistic training and ethics across the profession in Turkey.

Solutions for a freer press in Turkey

Turkey has made some progress in the past six months to address the issue of press freedom, but fundamental reforms are still needed.

Perhaps responding to international and domestic political pressure, the number of jailed journalists dropped sharply from 61 to 49 in December 2012 due to a number of releases, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Helping this process was progress on the Kurdish front, with direct negotiations between the AKP government and Abdullah Ӧcalan yielding a historic ceasefire announcement from the jailed PKK leader, who declared on March 21 that it was time to “solve the arms problem without losing time or another life.” This opening may help ease one of the points of tension resulting in many of the charges against journalists—the Kurdish issue—and prompt the government to embrace a broader alleviation of censorship.

The most recent positive development is an amendment to the Anti-Terror Law passed on April 11, 2013. The Turkish Parliament passed several AKP initiatives to narrow the definitions of prosecutable offenses, which are now limited to those who voice opinions deemed “a clear and an imminent danger to public order” or those who promote violent acts. While this limited step does not address the fundamental problems with the judicial system or the constitution and still leaves room for abuse under the “public order” clause, it is nevertheless a positive development.

Numerous reports have outlined in detail the steps necessary for Turkey to overcome this problem and fully institutionalize a vibrant and free press. First, Turkey’s EU accession process was a unifying thread that helped incentivize democratic governance, prevent the excesses of the security apparatus, and encourage reforms through the early AKP years—and hope is needed on that front. While politicians in Turkey have soured on EU accession of late because of Europe’s economic woes and the dismissive attitude of certain European leaders, Turkey’s entry into the union is in the interest of all parties.

Second, Turkey needs a new constitution. A modern democracy has no business being governed by a constitution written under military rule. The new constitution must prioritize the protection of minority rights and freedom of expression. This is not just meant as a protection for Kurds and other minorities, but also represents the only path to a peaceful, democratic Turkey, and will unleash new economic potential in previously marginal areas. Further, constitutional reform should include the removal of the most problematic “catch-all” phrases and clauses in the current constitution, particularly those regarding insulting the state or “Turkishness.” If Prime Minister Erdoğan wants to be remembered as Turkey’s democratic leader, then this should be his overarching goal.

Third, alongside the process of constitutional reform, the AKP must continue to pursue the evenhanded reform of the broken judicial system. The four judicial-reform packages passed since 2002 represent incremental progress, but the government would now be best served by bringing its full attention and resources to bear on the problem. As it stands, people accused of crimes spend far too long in jail awaiting trial, and release pending a trial is uneven and unfair. Related to this problem, trials proceed too slowly, contributing to the problem of long pretrial detentions and leading to financial and personal strain on the accused. Too often in Turkey, the accused are treated as guilty before due process has been served. The accused and their legal counsel must have full access to evidence, and the cloud of secrecy surrounding politically sensitive prosecutions should be removed. This will allow for greater accountability and will prevent overzealous prosecutors, often eager to gain favor by going after critics of the government, from abusing the broad definitions within the media law or the Anti-Terror Law.

Fourth, the Kurdish issue must be addressed through negotiation; military force alone will not solve the problem. To its credit, the AKP has begun this process, and negotiations continue with the departure of PKK fighters from Turkish soil pending a broader amnesty agreement. Much can still go wrong in this fraught political process, but the AKP has finally acknowledged that the only real way to end this struggle is to win the debate—not resort to force. And, of course, in order to win the debate, the AKP must allow the debate to take place.

Finally, the United States can and should do more to encourage its partner to more fully embrace its role as a modern democracy. All reports from both sides indicate that Prime Minister Erdoğan values his relationship with President Obama very highly. Beyond this personal relationship, Turkey and the United States share many strategic goals and a valuable military alliance. While policymakers must assess the value of public pronouncements given the political situations in both countries, private or personal appeals from President Obama might prompt action from Prime Minister Erdoğan. President Obama, Secretary of State John Kerry, and other members of the U.S. government should make clear to Turkish officials that the partnership does not end with military or strategic considerations. While making clear that Turkish democracy will continue to reflect Turkish culture and history, U.S. leaders must show that they consider freedom of the press to be non-negotiable.

Conclusion

The course of constitutional and legal reform in Turkey over the next two years, along with the fate of the PKK negotiations, will likely decide whether the events of the past five years represent either a necessary, if sometimes unpleasant, correction after so many years of military and Kemalist domination or a longer-term deterioration of democratic norms in Turkey. The 2014 presidential elections may also reveal the extent to which the current controversies are the product of specific leadership personalities or a case of the familiar tools of power wielded by new hands. It is unclear whether a figure less dominant than the prime minister would exert less control over the press or if the problem is more institutional.

But the blame must not be placed solely on the government, which is laboring under an outdated constitution and must deal with a stubborn opposition that mistrusts its intentions. Turkish politics must continue to address the wider problem of a political culture where the line between personal insult and outdated notions of honor and legitimate criticism or debate is blurred. Turkish society has also not fundamentally decided what balance of security and freedom of expression is right for their country—should reporting on bombings or carrying the statements of separatists be considered criminal? The question of media ownership is also thorny, with no indication that the trend toward consolidated ownership of news outlets by large conglomerates is slowing.

The owners of large media companies also often have a wide range of business interests with the government and fear that critiquing the AKP could negatively impact government contracts or other business operations. These overlapping interests and owners’ fears of government backlash have undoubtedly contributed to the current crisis of press freedom, with many proprietors applying pressure to journalists or editors who criticize the government. Indeed, a 2011 survey of top journalists by Bilgi University demonstrated the twin pressures facing journalists and editors, with 95 percent of those surveyed reporting government interference in news production and 85 percent reporting intervention by media owners.

What is certain is the central importance of press freedom to the entrenchment of democratic norms in Turkey. For nongovernmental organizations there is room to help monitor the situation and provide venues and support for independent journalism. Funding freelancers or helping set up independent publishing outlets along the lines of ProPublica could help circumvent many of the pressures placed on journalists in Turkey. A form of such adaptation is already going on with the rise of social media and the large online followings top journalists have acquired, but financial and institutional support are still lacking.

The United States has a clear interest in ensuring press freedom in Turkey. This interest extends beyond any general desire to promote democratic governance and freedom of expression and encompasses important strategic concerns. And the United States can be forthright in expecting more from Turkey’s leaders. Veteran U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Frank Ricciardone has been outspoken on the subject of political intervention in the Turkish press and has said that there is no need for high-level Turkish officials to constantly intervene. Ambassador Ricciardone is right to question the governing party’s efforts to suppress opinion.

Given Turkey’s history of coups and censorship, and the pluralism and diversity present in the early years of the AKP government, it is hard to understand why the prime minister and some of his cabinet members would risk those achievements, prompt a backlash from Turkish society, and damage the country’s international reputation by attempting to stifle dissent. Prime Minister Erdoğan and the AKP are strong enough and enjoy sufficient legitimacy to allow dissent and debate. Cracking down on such activities is a sign of weakness, not strength. Furthermore, the prime minister and his party have the opportunity to set a new tone in the political debate and to entrench a more open political culture.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton argued that, “The struggle for human rights begins by telling the truth over and over again,” affirming that the “United States will stand with those who seek to advance the causes of democracy and human rights wherever they may live.” This discussion represents the finest American tradition—even when there are political costs to advancing such issues—and it is in the U.S. interest to defend freedom of speech in close strategic allies such as Turkey.

Foreign policy and bilateral relations have become increasingly democratized in this modern era, requiring more debate and engagement on questions of legitimacy, and “intermestic” concerns have gained prominence. Secretary Clinton’s drive to engage societies in addition to governments recognized this phenomenon, and this approach should be more fully extended to Turkey. That is precisely why President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry should consistently raise the subject in meetings with Prime Minister Erdoğan and Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu. If personal assurances are not backed up by substantive action, more public exhortations may be necessary.

The United States and Turkey have a solid strategic partnership on which to build, but in the long run, deepening this association—which is in both countries’ national interest and is sought by many on both sides—will require a shared understanding of freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

Michael Werz is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Max Hoffman is a Research Associate at the Center.

This project was made possible in part by support from the Open Society Foundation—Turkey.