Introduction

On Wednesday, March 21, the U.S. Department of the Interior hosted an auction for offshore drilling rights in the Gulf of Mexico, which the Trump administration has for months been touting as the “largest oil and gas lease sale in U.S. history.” For only the second time since 1983, Interior officials put all three planning areas of the Gulf of Mexico on the auction block at the same time, in a so-called regionwide sale. By simultaneously offering drilling rights across the Western Gulf, Central Gulf, and the small portion of the Eastern Gulf not subject to the congressional moratorium designed to protect Florida’s beaches from oil spills, the Trump administration’s regionwide sale encompassed more acreage than any prior auction.

The Department of the Interior claims that this regionwide sale will create jobs and substantiate the president’s dubious “energy dominance” slogan by boosting oil and gas production. But when a business sells off inventory at prices below market value, buyers tend to be the only winners.

Furthermore, as with other grand claims issued by the Trump administration over the past 13 months, a closer look at the results of Wednesday’s auction reveals that the truth is much less impressive than the rhetoric. It also reveals that the government’s regionwide approach to granting oil leases is fiscally, legally, and environmentally problematic, dramatically undervaluing America’s natural resources and putting taxpayers, fisheries, and coastal economies at risk.

Neither the largest sale in U.S. history, nor the most legally sound

The federal law underpinning offshore oil and gas development—the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act—requires that the Department of the Interior only grant leases of publicly owned offshore resources to qualified bidders through “competitive bidding” and that federal offshore leasing “shall be conducted to assure receipt of fair market value for the lands leased.”

In spite of this clear legal mandate for the parameters of stewardship, the Trump administration’s actions on offshore drilling policy, including last week’s regionwide auction, are flooding the market for leases at a time of low industry interest, eliminating competition among bidders, and minimizing the returns to American taxpayers—to whom the resources belong.

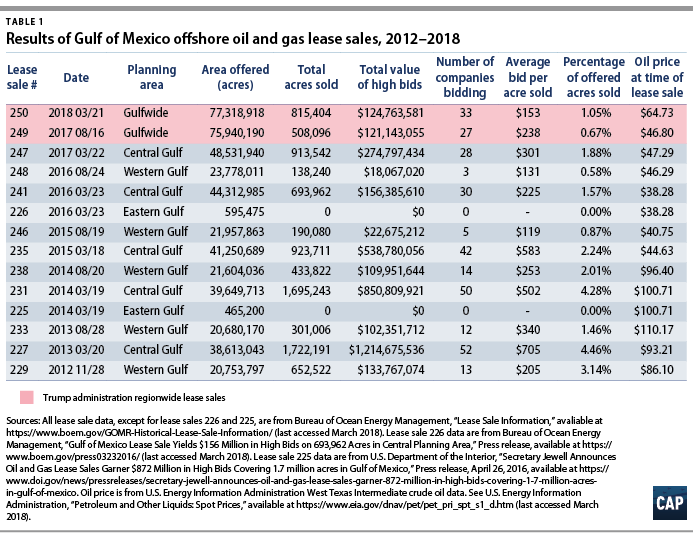

Comparing the prices of last Wednesday’s lease sale to those of areawide lease sales over the past several years is illustrative. To have plausibly been considered a success in meeting the administration’s “largest ever” rhetoric, the auction should have yielded more total high bids, a higher average bid per acre, and more acres sold than the combined average of Central, Eastern, and Western Gulf of Mexico sales in recent years.

In other words, if the Trump administration were to have held separate lease auctions for the Central Gulf, Western Gulf, and Eastern Gulf planning areas, it could have expected—based on the sum of average results of areawide lease sales since 2012—to have sold a total of 1.53 million acres across the entire Gulf, received at least $684 million in total high bids, and collected at least $446 per acre.

Instead, Wednesday’s regionwide lease sale fell short of this standard on all measures. Drilling companies bid on a total of 815,403 acres across the entire Gulf, with a total of only $124.8 million in high bids. This averages out to only $153 per acre. The Trump administration’s “largest lease sale in U.S. history” sold 1.05 percent of the 77.3 million acres offered.

Moving an already flawed program in the wrong direction

From 1983 to 2016, offshore lease sales were typically offered one planning area at a time. For example, Interior conducted an areawide auction for the Central Gulf of Mexico planning area south of Louisiana annually from 2007 through 2016—with the exception of 2010, when the auction was canceled due to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Although an areawide approach is more selective than the Trump administration’s new regionwide lease auctions, results from recent years show that even these smaller sales were already oversupplying the market for drilling rights, driving down the prices. In a recent analysis, the Project on Government Oversight found that of the 13,212 federal offshore drilling tracts won at auction from 1997 to 2017, more than 76 percent of them were won by a single, uncontested bid. Wednesday’s lease sale took this dynamic a step further: Only 10 of the 148 parcels sold had more than one bidder, meaning that 93 percent of sales were noncompetitive.

Through its regionwide lease sales, the Trump administration has chosen to substantially increase the supply of drilling rights available at auction, thereby moving the program toward even less competition and a further devaluation of publicly owned resources. While there are certainly different levels of oil and gas resource quality among different tracts of subsea lands, the administration’s approach lets every bidder be a winner. By giving oil companies better than a 9 out of 10 chance that they will not have to compete for drilling rights when they bid—as they enjoyed during last week’s regionwide auction—industry faces little incentive to pay its fair share to the American people.

Regionwide lease sales represent bad policy not just because they contravene taxpayer-protection provisions of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act; there is also no evidence that they alleviate any purported constraints on offshore production or employment. Since 2012, the most successful lease auction in terms of acres sold occurred in 2013 (lease sale 227), during which industry bought 1.72 million acres within the Central Gulf planning area alone for $1.21 billion in total high bids. That 2013 areawide sale dramatically outperformed Wednesday’s regionwide auction, as well as the Trump administration’s first regionwide lease sale in August 2017. Yet that comparatively vibrant 2013 auction still sold only 4.41 percent of the 39 million acres offered. Meanwhile, Gulf of Mexico crude oil production has hovered between 400 million and 600 million barrels of oil per year since 1997. Regionwide sales are a solution in search of a problem.

Accelerating the sell-off, expanding the risk

As with most industries, the scale of offshore oil and gas activity depends most heavily on the price of the product it produces. Today, a global glut of crude oil—topped off by revolutionary levels of output from Texas and North Dakota shale formations—has continued to temper prices. Meanwhile, the United States is already exporting record levels of petroleum products, following Congress’ vote to lift a long-standing ban on crude oil exportation in 2015. New offshore oil prospects are significantly more expensive to develop than the booming onshore fields and therefore are not that appealing to the petroleum industry, as analysts from S&P Global Platts recently summarized. In an attempt to counter industry disinterest and inflate demand for new offshore leases, the Trump administration lowered the required royalty rates that oil producers must pay per barrel of oil produced, further padding industry profit margins at taxpayer expense.

In this tepid market, regionwide lease sales and royalty rate cuts are the equivalent of trying to sell on the low, never a rewarding business strategy.

Meanwhile, offshore drilling remains profoundly risky for the marine environment, commercial and recreational fisheries, and coastal economies that depend on clean oceans and beaches. Just eight years ago, the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster began with a violent explosion in the Central Gulf of Mexico planning area, taking the lives of 11 rig workers and ultimately costing more than $65 billion to clean up. According to federal data, industry caused 334 additional spills from 2006 to 2015. In fall 2017, nearly 10,000 barrels spilled again in the Gulf, 40 miles south of Louisiana. The data show that spills are an inevitable byproduct of drilling activity; expanding offshore drilling necessarily means more oil spills.

Yet even as the Interior Department pursues the sell-off of America’s oceans through regionwide, cut-rate lease sales, it has also taken steps to reduce drilling safety and dramatically expand the practice beyond the Gulf of Mexico. At the behest of the oil companies most often cited for safety violations, the administration has initiated a rollback of basic offshore drilling safety measures that were established after Deepwater Horizon—based on the 2011 recommendations of a bipartisan presidential commission—to prevent the recurrence of such a calamity. And in early January 2018, the Trump administration proposed to open more than 90 percent of U.S. federal waters to drilling, including high-risk areas in the Arctic Ocean and off the shores of Atlantic and Pacific states, whose coastal economies are profoundly vulnerable to the impacts of an oil spill.

Conclusion

The poor result of last week’s offshore lease sale is just the latest failure of the Trump administration’s self-hyped oil and gas leasing program. In October 2017, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke boasted that his plan to lease 10.3 million acres in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska was “unprecedented” and “will help achieve our goal of American Energy Dominance.” The lease sale, however, generated bids on less than 1 percent of the lands offered and netted taxpayers only $1.16 million. Nationally, the Trump administration offered oil and gas companies six times more public land for drilling in 2017 than was offered in 2016, but oil and gas companies actually bought fewer acres, and a higher proportion of the acres sold went for the minimum bid of $2 per acre. In other words—both in the oceans and on public lands—the Trump administration is trying to sell more but is getting less for American taxpayers.

Rather than provide sound stewardship of America’s natural resources in accordance with federal law, the Trump administration and Secretary Zinke seem committed to selling off America’s oceans at the lowest possible prices, for oil and gas drilling under a minimum of independent oversight. While the Interior Department attempts to put a positive spin on the middling returns from Wednesday’s lease sale, the results demonstrate a federal agenda for America’s oceans in which one special interest—the oil and gas industry—is the only winner.

Shiva Polefka is the associate director for Ocean Policy at the Center for American Progress. Matt Lee-Ashley is a senior fellow at the Center.

Mary Ellen Kustin, director of policy for Public Lands; Michael Conathan, director of Oceans Policy; and Emily Haynes, assistant managing editor, all at the Center, provided essential contributions to this column.