When the federal government last changed its royalty rate for oil and gas production on America’s public lands, Standard Oil’s monopoly had only recently been broken, Ford’s Model A still had not rolled off the assembly line, the Teapot Dome scandal had yet to erupt and rock the U.S. Department of the Interior and the administration of President Warren G. Harding, and the 20s had just begun to roar. In the 95 years since the Mineral Leasing Act first set the federal royalty rate for oil and gas at 12.5 percent, the federal government’s oil and gas revenue policies have remained firmly fixed in the past while state governments and private landowners have, time and again, updated the terms for development on their lands.

As a result of the federal government’s failure to modernize its oil and gas program, U.S. taxpayers are losing out on more than $730 million in revenue every year. At the same time, oil and gas companies are stockpiling leases and sitting idle on the rights to drill on tens of millions of acres of public lands. When companies have drilled for oil and gas, the American public has often been left footing the bill to clean up the environmental damage that has been left behind.

On April 17, the Obama administration signaled that it would undertake much-needed reforms to bring the federal government’s oil and gas program into the 21st century. Through what is known as an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, or ANPR, the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, is accepting ideas on how to reform its royalty rates, bonding requirements, minimum bids, and rental rates. These reforms will ensure that taxpayers are fairly compensated for the development of their resources and that companies are held responsible for paying for any clean up related to their drilling activity.

This issue brief provides a short introduction to current oil and gas revenue policy, looks at the specific areas of that policy the Obama administration has pledged to examine, and finally, suggests some common sense ideas for reform.

Royalties

U.S. federal oil and gas royalties are payments made by companies to the federal government for the oil and gas extracted on public lands and waters. With a royalty, owners of the resource—in this case, U.S. taxpayers—collect a share of the profits based on the value or volume of the oil and gas extracted. On taxpayer-owned federal lands such as those managed by the U.S. Forest Service and BLM, oil and gas companies pay royalties to the U.S. Treasury, making royalties one of the federal government’s largest nontax sources of revenue. With the exception of Alaska, the revenue is split with about half going to the Treasury and half going to the state where the federal lease is located. While all taxpayers have a financial interest in ensuring that royalties on federal lands deliver a fair return, oil and gas producing states—primarily those concentrated in the West—have a particular high stake, as this money goes to fund schools, roads, and other priorities.

Currently, the federal government charges a royalty of only 12.5 percent on oil and gas extracted from public land. This rate has not been updated since 1920; since then, technological advances and changing markets have made oil and gas extraction more efficient and much more lucrative. In 2014, the big five oil companies—BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil, and Shell—made $90 billion in profits.

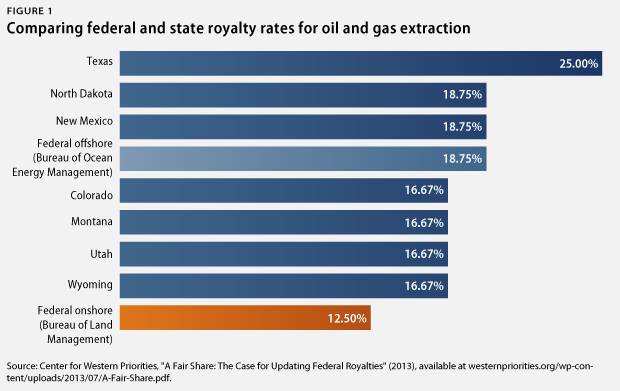

In response to changing market dynamics and to better reflect modern drilling practices, state and private landowners have updated their royalty rates. Texas charges a 25 percent royalty for leases on the state’s university and school lands—state land set aside to financially support these state institutions –while New Mexico and North Dakota charge 18.75 percent for oil and gas production on public lands. Many western states, including Wyoming, Utah, Montana, and Colorado, charge a 16.67 percent royalty rate on state-owned leases. A CAP review found that private landowners are also charging higher royalty rates than the federal government. For example, lease documents in Texas and Louisiana show private landowners charging oil and gas companies a 25 percent royalty on resources extracted from their land.

What’s more, the royalty rate on federal lands is 50 percent lower than the royalty rate for drilling in federal waters on the Outer Continental Shelf. The administration of former President George W. Bush twice increased the royalty rate for offshore drilling to its current level of 18.75 percent. According to the Center for Western Priorities, if the onshore federal royalty rate were the same as the offshore rate, the U.S. government would collect an additional $730 million every year. A review by the Government Accountability Office, or GAO, also found that, when compared to other countries, the royalty rate for drilling on U.S. federal lands is one of the lowest in the world.

In its ANPR announcement that it will publish a new rule to modernize the BLM’s oil and gas revenue policies, the Obama administration asked for input on a range of potential royalty structures, including a fixed royalty rate and a flexible royalty rate that could be adjusted in response to changing market conditions. Based on a review of royalty provisions on state and private lands, CAPrecommends that the new regulations set a floor of 18.75 percent for the royalty rate, while allowing the secretary of the Interior the discretion to raise the rate in response to market conditions, without further rulemaking. In a recent report—“A Fair Share: The Case for Updating Federal Royalties”—the Center for Western Priorities suggested a sliding-scale royalty where the secretary of the Interior can increase rates based on either oil and natural gas prices or the location of known resources where the rate might increase in an area of known production versus an area that is more speculative.

The concept of setting a new floor for the royalty rate while allowing discretion to increase the rate above that floor is similar to the policies governing the surface mining of coal on public lands. This rule change would also represent a common sense expansion of the authority of the secretary of the Interior to implement a sliding-scale royalty on particular oil and gas leases in limited circumstances. It is vital, however, that the administration set a higher floor than 12.5 percent for the royalty rate; without a floor, future royalty policy will be highly susceptible to political pressure to provide royalty breaks at the expense of American taxpayers.

For its part, the oil and gas industry has long argued that higher royalty rates will result in a major decrease in production; however, the evidence does not support their claims. The Permian Basin in west Texas, for example, has been the site of the greatest regional increase in oil and gas production in the past eight years with daily oil output more than doubling during that time from 850,000 barrels per day to nearly 2 million barrels per day. Much of the development and production in the Permian Basin is occurring on the University of Texas System’s University Lands, on which oil and gas companies pay a 25 percent royalty.

From a resource perspective, the Permian Basin is no outlier. According to the U.S. Geological Survey and Potential Gas Committee—composed of oil and gas industry experts—advances in drilling and exploration technology give the Rocky Mountains and other areas in the West similar hydrocarbon potential to the Permian Basin; that is to say, they have strong potentials for significant and economically viable oil and gas reservoirs. Given that much of these future plays for oil and gas extraction are on U.S. public lands, it is all the more urgent that the Obama administration raise royalty rates before taxpayers miss out on their share of the profits.

Bonding

When an oil and gas company successfully bids on a lease, it must post a bond—or insurance—to guarantee that it will comply with the terms of the lease, including cleanup costs for unseen disasters during production and after the well stops producing. The bonding requirements on federal land have not been updated in more than 50 years. Currently, under regulations set in 1951, a company can secure a nationwide bond for all its oil and gas wells on public lands for only $150,000. Adjusting for inflation, that $150,000 fee would be nearly $1.4 million in 2015 dollars. Following this same inflation calculation, statewide bonding would increase from $25,000 to $270,500, and an individual lease bond—set in 1960—would increase from $10,000 to $80,000.

Because companies are able to pay so little for statewide and nationwide bonds, bonding for individual wells can be as low as $50 per well.In Wyoming in 2008, the cost of cleaning up a single gas or oil well was as high as $582,829. The state of Wyoming estimates that the average cost of clean up and reclamation of a single well is between $2,500 and $7,500; this estimate does not include reclamation costs for other parts of oil and gas operations such as decommissioning roads, compressor station sites, and containment ponds. Some estimates are much higher. According to the head of the University of Wyoming’s Agriculture and Applied Economics Department, it costs around $30,000 to reclaim just one oil or gas well.

CAP recommends that the Obama administration update current rules to set bonding requirements based on the number of wells that would need to be reclaimed. The Texas Railroad Commission, for example, requires that a company post $25,000 for 10 or fewer wells; $50,000 for between 10 and 100 wells; and $250,000 for 100 or more wells. Based on reclamation cost estimates, even these requirements appear to be too low to cover potential cleanup costs. The required bond per well should reflect the average cost of reclamation for each site to shield taxpayers from the cost of cleanup. Some experts have called for a bond of $20,000 per well, and further bond requirements for additional facilities associated with the drilling operations.

Minimum acceptable bonus bids

A bonus bid is the payment that an oil and gas company offers to purchase a lease on public lands. If accepted by the federal government, the bonus bid grants the company the right to drill on the leased land for a period of 10 years. The BLM currently requires a company’s bonus bid to be at least $2 per acre—known as the minimum bid—to win the right to drill on a lease.

Under the current federal leasing process, the land parcels that the BLM offers for lease are typically nominated, or suggested to the BLM, by the oil and gas companies. By nominating a parcel, companies are expressing a financial interest in the land and, in theory, should be willing to pay a fair price for the leases. Yet, in the first quarter of 2015, 25 percent of the federal leases sold in seven western states were sold for $2 per acre, the minimum bid. Further, noncompetitive issued leases—where there was no bid offered for at least two years—account for 40 percent of BLM leases in place today. This large proportion of leases going for the minimum bid of $2 per acre should be of concern to both policymakers and taxpayers.

In many cases, bonus bids on federal public lands are significantly higher than the minimum bid, suggesting that the floor can and should be raised. For example, the highest bid in the most recent lease sale for federal parcels in Colorado, held in May 2015, was $10,100 per acre. For federal parcels in Montana, the highest bonus bid was also in a May 2015 lease sale and was $825 per acre. In Utah, it was $500 an acre. Similarly, the average bonus bids per acre were also much higher than the minimum bid in the most recent lease sales in Wyoming, where the average bonus bid was $21 per acre and in Utah, with the average bid at $19 per acre. Bonus bids on state-owned lands also appear to be well above the federal government’s minimum bid. The highest bid in the most recent lease sale in Texas for University Lands went for $6,503 per acre.

According to some experts, the minimum acceptable bid should be raised to account for the so-called option value of the resource. The option value—or ability to delay a decision until more information is available—is a concept that has long been incorporated into natural resources law to account for the uncertainty around markets, technology, and environmental and social costs. When the federal government sells a lease, it sells the taxpayers’ future option to develop those resources, even if the lease would be more lucrative at some future date. When the federal government leases a parcel for oil and gas drilling, for example, it also sells the public’s future option to use that land in some other way and for some other purpose. Therefore, the minimum bid should be raised to ensure taxpayers are fairly compensated for losing the ability to exploit these resources in the future when conditions may be more favorable or to prevent the loss of a more valuable use of the land. It can similarly be argued that the government should not issue noncompetitive leases. If the market is not driving a fair price for these lands, the government should take full advantage of the option value and steward taxpayers’ resources for a more favorable time or use.

Rental rates

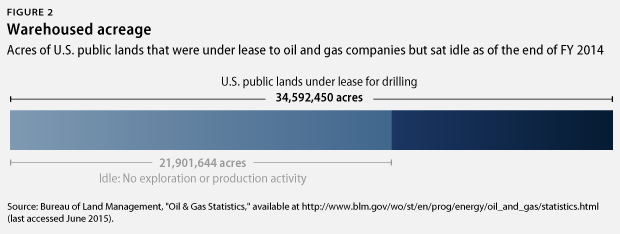

To preserve their rights to drill on a lease, the leaseholder is required to pay an annual rental fee to the federal government. Current rental rates are set at $1.50 per acre for the first five years of a lease, and $2 per acre thereafter. In its announcement of the upcoming rulemaking on oil and gas, the Obama administration asked for input on how to create “greater financial incentive for oil and gas companies to develop their leases promptly or relinquish them.” Indeed, oil and gas companies routinely sit idle on nonproducing leases, placing these areas off limits to the American public, which owns them. At the end of fiscal year 2014, more than 34.5 million acres of federal lands were under lease for oil and gas, yet only about 12.7 million of those acres—less than 37 percent—were actually producing oil or gas.

The Texas General Land Office, which manages the land owned by the state for the benefit of public education, has created an incentive to use or relinquish leases on the state’s school lands by using a graduated rental rate. In the first two years of a lease, the rental rate is $5 per acre. In the third year of the lease, that rate jumps to $2,500 per acre to incentivize drilling or turning the lease back over to the citizens of Texas. Leases on federal public lands have 10-year terms, but the federal government could adopt an approach similar to Texas. CAP recommends that the federal government raise rental rates in the fourth or fifth year of a lease to disincentivize leaseholders from sitting idle on their rights to drill on public lands.

In Texas, oil and gas leases on University Lands require companies to prepay rental fees for all three years of the lease term, as do many private landowners. This discourages oil and gas companies from buying leases for the purpose of holding them and then reselling them when the market improves, undercutting the American taxpayer. However the deterrent effect of a “paid-up” lease would require that rental rates be high enough to more accurately represent the value of the land. One oil and gas company in New Mexico has argued that rental rates should be at least $100 per acre, noting that this price would not dissuade companies from bidding on leases. This company also argues that paying a full rental payment up front eliminates the confusing and time-consuming process of paying rental fees each year.

Conclusion

Under the current royalty rates, bonding requirements, minimum bids, and rental rates on public lands—some of which have not been updated in nearly a century—American taxpayers and energy-producing states are not receiving a fair return from the development of their valuable resources. From a business perspective, the federal government is lagging behind states and private landowners in defending the financial interests of their shareholders: American taxpayers. The upcoming rulemaking that addresses the federal oil and gas leasing process is a critical opportunity for the Obama administration to reevaluate how public lands are leased and ensure that the public receives a fair and equitable share of these shared resources.

Nicole Gentile is the Director of Campaigns with the Public Lands Project at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Carl Chancellor, Anne Paisley, Emily Haynes, and Alexis Evangelos for their contributions.