See also: “Watching the Watchdogs: A Look at What Happens When Accreditors Sanction Colleges” by Antoinette Flores1

As gatekeepers that control whether colleges can receive federal financial aid, accrediting agencies play a critical role in ensuring the quality of postsecondary institutions. The actions an accrediting agency takes when a college fails to meet quality standards play an important role in protecting students, taxpayers, and policymakers.

Unfortunately, Center for American Progress’ review of the actions agencies had taken against underperforming colleges found a highly inconsistent system of sanctions. Accreditors’ practices differ in how frequently they take serious action, how many colleges under sanction lose accreditation, and how long colleges remain on sanction. Agencies use basic terms and definitions differently, and some fail to reveal publicly why a college is placed on sanction.

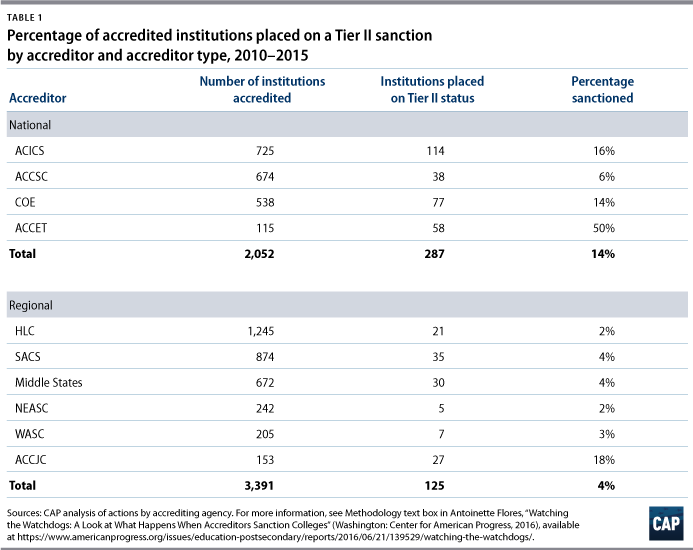

Here is an example of how little uniformity exists: Some agencies use the term “warning” to indicate a low level of concern about a college; other agencies use the term “notice”; and others do not have any sanction available to reflect low concern. Most agencies use the terms “probation” or “show cause” to reflect a high level of concern. Some agencies, however, impose probation before escalating to show cause, while others do just the opposite. Some agencies only use one or the other. Sanctions reflecting a serious level of concern—such as probation and show cause—are referred to here as Tier II sanctions.

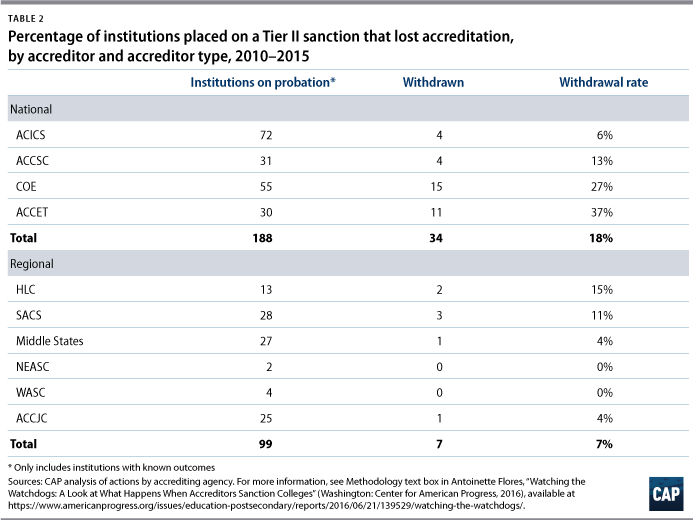

National accreditation agencies, which oversee mostly for-profit, career-focused programs, are significantly more likely than regional agencies to place institutions on serious sanction. They are also more likely to withdraw accreditation from colleges on sanction. This may just be a function of the types of schools national agencies accredit. Many of the schools that national accreditors oversee are small privately run businesses and depend almost entirely on enrollment and student aid for revenue. Therefore, they may be less financially stable than public colleges and private nonprofits, which have various revenue sources, including state and local funding support.

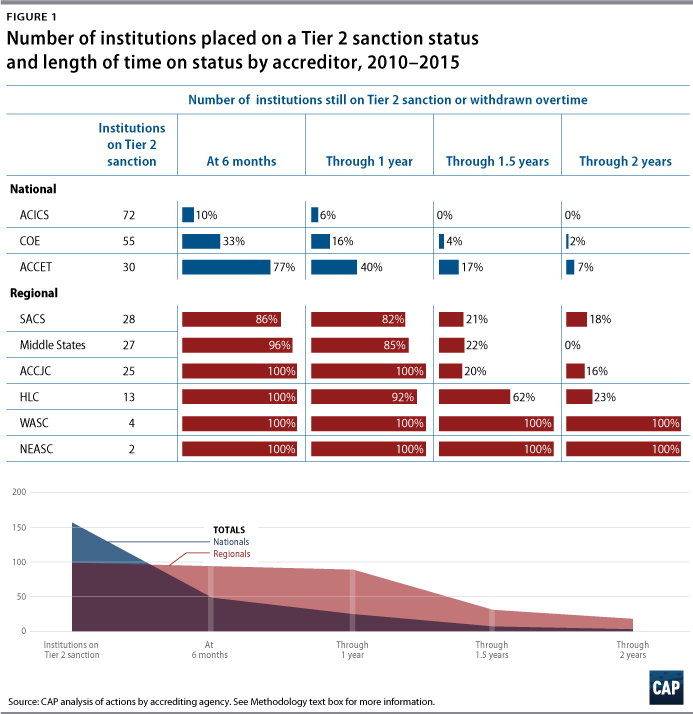

Although regional agencies, which oversee mostly public and private nonprofit colleges, are less likely to sanction colleges and withdraw accreditation, they keep sanctioned colleges under scrutiny for a longer period of time than national agencies.

The author’s findings show an inconsistent system where some accreditors are more likely than others to sanction colleges and rescind their access to federal dollars. Some accreditors use sanctions as long-term monitoring and improvement tools, while others use sanctions on a much shorter timeline. Fixing the system and restoring faith in accreditation requires a serious look at how those processes can be improved.

Recommendations

- Standardize accreditor sanction terminology. Clear terms and definitions can help the public and the federal government understand the seriousness and implications of the actions agencies take. Congress can require a single federal definition for all major actions and terms, including sanctions and key outcomes, to fix the current inconsistencies.

- Standardize the application of accreditor sanctions. The author’s analysis found that different accreditors use the same type of sanction in different ways—sometimes as a quick reprimand and sometimes as the basis for ongoing monitoring. Serious sanctions should be applied for similar time frames across agencies. A standard timeline needs to account for a minimum time for how long it should reasonably take an institution to improve. No institution should be given an all-clear before the minimum sanction period ends.

- Increase transparency and disclosure, including on reasons why sanctions are issued and evidence they should be removed. To improve the oversight system, accreditors should be required to inform the U.S. Department of Education and the public when they issue or remove a sanction and provide an explanation of why the sanction was issued or removed. Sanctioned colleges should be required to publicly disclose sanctions and inform all current and prospective students.

- Update and improve the database of accrediting decisions. The Obama administration created an accreditor reporting portal that, in theory, should include a history of accreditor decisions, including reasons for sanctions’ enforcement and removal. Not all agencies are currently following the guidance and submitting necessary documents. Further, the information is not being used to create a searchable, historical public record of accreditor actions as intended.

Antoinette Flores is an associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.