See also: A Great Recession, a Great Retreat by David A. Bergeron, Elizabeth Baylor, and Antoinette Flores

The economic downturn and financial crisis that occurred from December 2007 to June 2009, known as the Great Recession, disrupted both domestic and world markets. In the United States, millions of Americans lost their jobs, and families saw their homes foreclosed. And in the years since this recession—and particularly when the nation’s economy began to recover—the gains made have not been evenly distributed among those who suffered economic losses. In fact, economic opportunities eroded faster for communities of color during the recession compared to non-Hispanic whites. Moreover, the opportunities that have returned during the recovery are arriving slower for communities of color.

With unemployment rates skyrocketing during the Great Recession, many unemployed Americans went back to school as nontraditional adult students in order to retool their skills and rebuild their careers. These nontraditional students primarily attended two-year, public postsecondary institutions, such as local community colleges. Simultaneously, among traditional students, community colleges saw a greater increase than four-year institutions for a variety of reasons, including the lower cost of two-year institutions, potential enrollment caps at four-year institutions, and the lowered opportunity costs of postsecondary education compared to unemployment. Since the Great Recession, community colleges have seen a 20 percent increase in enrollment, while four-year public universities have seen an increase of only 10.6 percent.

The recession not only affected individuals’ economic outlook, but also their educational outlook. During the recession, state budgets shrunk and difficult decisions had to be made on where to cut spending; one result was a reduction of state support for postsecondary educational institutions, of which two-year institutions bore much of the brunt. Thus, while enrollment at two-year institutions increased during the recession, the increase in enrollment was not met with an increase in funding. When accounting for enrollment trends, community colleges were more likely to experience a decline in funding per student than four-year institutions. Based on spending per full-time equivalent, or FTE, enrollment 45 states have decreased funding at two-year institutions. And while four-year institutions also saw a fall in funding, 31 states had a decline in funding for community colleges at a greater rate than public universities.

In addition to more severe funding cuts than those at four-year institutions, the additional enrollment at community colleges compared to four-year institutions resulted in the further decline of funding per student. The countercyclical trend of increased enrollment during an economic downturn is not unexpected. Yet, states often disinvest in institutions when students need them the most. Aside from unemployed workers returning to school during times of high unemployment, students attending two-year institutions are much more likely to be first-generation students, students of color, and students from low-income families. Nationwide, people of color made up 38 percent of undergraduate fall enrollment in 2009, but community colleges have generally enrolled half of the student-of-color undergraduate population. Considering that communities of color only make up around 37 percent of the population as of 2013, it is clear that community colleges disproportionately serve communities of color.

Communities of color are growing. The Census Bureau projects they will make up the majority of the nation’s population sometime around 2043 and thus are poised to become a bigger share of our nation’s higher-education system. In fact, this year, students of color are projected to be the majority of public K-12 students for the first time in history. And in the next eight years, enrollment of students of color in postsecondary institutions is projected to grow to 41 percent of the total enrollment population.

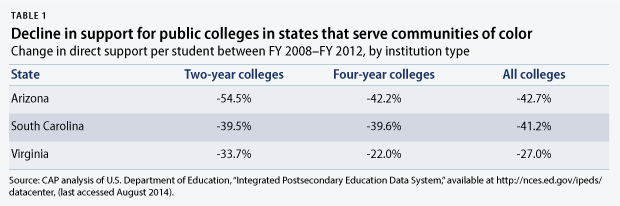

Given the changing face of our nation, it is more important than ever for states to invest in the educational future of communities of color. Some states already have gone through or are currently going through these demographic shifts. For example, 60 percent of California residents are people of color. In South Carolina, Virginia, and Arizona, the resident population of people of color is 36 percent, 36 percent, and 43 percent, respectively. The success of community colleges and other minority-serving institutions in these states with growing communities of color is critical. Yet, these three states are among those who have cut spending per student the most since the Great Recession. Spending dropped by 41 percent in South Carolina during this period, by 27 percent in Virginia, and by 43 percent in Arizona. As mentioned, the spending reductions have not been uniform across institutions.

In Virginia, for example, two-year institutions saw their per-student funding reduced by 33.7 percent, while four-year institutions saw a reduction of 22 percent. (see Table 2) Interestingly, The University of Virginia, the state’s flagship institution, only saw a 17 percent reduction, affecting a student body that is 24 percent students of color: 10 percent Asian American, 6 percent African American, 5 percent Hispanic, and 3 percent multiracial. Whereas Northern Virginia Community College, with 53 percent of its student body students of color—14 percent Asian American, 1 percent Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 17 percent African American, 18 percent Hispanic, and 3 percent multiracial—saw a reduction in funding of close to 44 percent. Two of Virginia’s historically black public colleges and universities—Virginia State University and Norfolk State University—saw cuts that were significantly smaller than those at The University of Virginia, indicating that some minority-serving institutions were spared deep cuts while others were not.

South Carolina saw a 39.5 percent reduction in spending on two-year institutions—similar to a 39.6 percent reduction among four-year institutions—but cuts were not uniform at all institutions. Its flagship institution, University of South Carolina, whose student body is 21 percent students of color, saw a funding cut of 28 percent. In comparison, South Carolina State University, a four-year institution whose student body is almost entirely students of color—94 percent African American, 1 percent Hispanic—was cut by 43.5 percent. Meanwhile, Denmark Technical College, a two-year institution with a 96 percent African American student body, saw a funding reduction of 52 percent.

Even in stable economic times, communities of color are relying more and more on community colleges as an access point to low-cost, postsecondary education. Yet, during hard economic times—when people need alternatives to employment the most—funding for two-year institutions that primarily serve this community has shrunk severely as state budgets tighten. This trend suggests a need for a new approach to investing in accessible postsecondary education, as well as a new approach to supporting families during economic downturns.

In order to make postsecondary education affordable and attainable during both strong and weak economic times, the Center for American Progress recommends the creation of a Public College Quality Compact that would combine grant funding from the federal government with state support to maintain the levels of investment in public universities and community colleges. This compact would be a competitive matching grant program established by the federal government with the purpose of encouraging state reinvestment in higher education. To receive a grant, states would need to match the federal grants and would be required to do the following:

- Create reliable funding by building new funding streams, ensuring that students and prospective students can prepare for and enroll in postsecondary education with certainty

- Make college affordable by guaranteeing that low-income students will receive grant aid from the compact to cover their enrollment at public institutions

- Improve performance by setting outcome goals for institutions, such as increased graduation rates

- Remove barriers and state and institutional policies that stand in the way of college completion

This compact would improve value by implementing policies that maintain or increase the quality of programs while keeping costs down. Quality, affordable postsecondary education is not only necessary for low-income students, returning students, and students of color; it is an economic imperative for everyone. By 2020, two-thirds of job openings will require some postsecondary education, and the United States is at risk of not having enough workers with the necessary levels of education. As the United States and its workforce become increasingly diverse, making quality, affordable postsecondary education available to all both increases the accessibility of education for students of color and supports the U.S. economy.

Read more about the details in our report, “A Great Recession, a Great Retreat.”

Farah Z. Ahmad is a Policy Analyst for Progress 2050 at American Progress.

The author would like to thank David Bergeron, Elizabeth Baylor, and Antoinette Flores for reviewing and providing valuable input and content for this issue brief.