World leaders are set to meet in September 2015 to agree on a set of goals to replace the Millennium Development Goals, which will expire in 2015. People from all over the world have been engaged in opining, discussing, debating, and even voting on what those new goals should be.

While significant attention is being paid to the vision of the post-2015 agenda, less attention has focused on the details of how to achieve this vision by 2030, the assumed deadline for the next set of goals.

Fortunately, the conversation is now turning from the “what” to the “how” with the recent announcement of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, or FFD, conference to take place in July 2015 in Addis Ababa, just ahead of the September 2015 U.N. summit to adopt the post-2015 framework.

The Addis conference will focus on channeling the resources and tools necessary to achieve the new set of development goals. The proposed goals submitted to the U.N. General Assembly cover a broad range of issues, from economic growth to social issues to global public goods. The post-2015 agenda will be much more ambitious than the MDGs. To have any chance of realizing this vision, a just-as-ambitious plan for financing and implementation is needed.

Definitions

Advanced market commitment, or AMC: A legally binding agreement for an amount of funds to subsidize the purchase, at a given price, of an as-yet-unavailable vaccine against a specific disease that causes high morbidity and mortality in developing countries. AMCs incentivize pharmaceutical companies to develop innovative vaccines.

Bilateral export credits: Export credits are government financial supports that facilitate the sale of national goods abroad through loans, risk guarantees, and insurance.

Concessional flows: Loans extended on terms that are more generous than market loans. The concessionality is achieved either through interest rates below those available on the market, grace periods, or a combination of these. Concessional loans typically have long grace periods.

Foreign direct investment, or FDI: The category of international investment that reflects the objective of a resident entity in one economy to obtain a lasting interest in an enterprise resident in another economy.

Official development assistance, or ODA: Government aid designed to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries, but does not include loans and credits for military purposes. Aid may be transferred bilaterally, from government to government, or through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank or United Nations.

Other official flows, or OOF: Transactions by the official sector with countries on the list of aid recipients that do not meet the conditions for eligibility as ODA, either because they are not primarily aimed at development, or because they have a grant element of less than 25 percent.

The MDGs’ financing and implementation policies were not agreed upon until the 2002 Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development—two years after the Millennium Declaration, which set out commitments for poverty eradication, development, and the environment, was signed. Holding the financing conversation earlier in the process is a welcome development, one proposed by the High Level Panel on Post-2015—on which CAP founder and former Chair John Podesta served—which called for a conference “in the first half of 2015 to address in practical terms how to finance the post-2015 agenda.”

The timing does, however, raise the stakes: The FFD conference will be the first of four major multilateral meetings in 2015, followed by the September Heads of State and Government Summit to agree to the next development agenda; the December U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, Conference of Parties meeting in Paris to agree to a climate treaty; and the December ministerial-level meeting of the World Trade Organization. Though these are separate processes, they are substantively interlinked. With FFD occurring first in this sequence, there will be significant pressure for a successful agreement to lay the foundation for agreements in the other major multilateral venues.

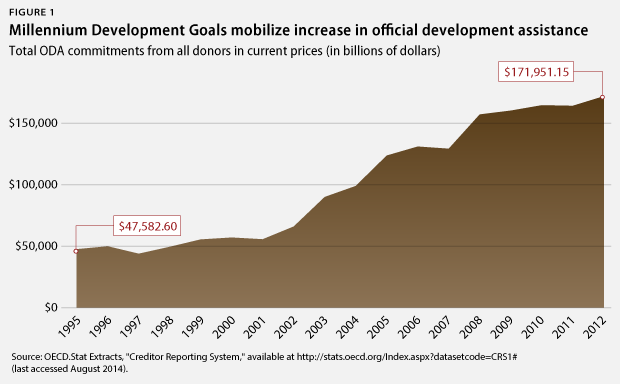

In addition to the timing, the content of the discussion will be more challenging than that at Monterrey. Monterrey embodied an implicit bargain between donors and developing countries, though middle-income countries’ interests received relatively less attention. It solidified support for more official development assistance, or ODA, from donor countries—reversing a decade of decline in aid flows—in return for developing countries committing to social reforms in key goal areas, such as poverty, health, and education. A 2008 follow-up conference in Doha, Qatar, reiterated this commitment, even in the midst of the financial crisis.

Such a bargain will not work this time around. Seismic economic shifts have overturned the development landscape: Some of the world’s largest economies are home to the largest numbers of people living in extreme poverty, while traditional donor countries are struggling with slow growth and sluggish economies. And the next development agenda is likely to be universal, meaning that the goals will be relevant for all countries, not just low-income countries. The political deal that needs to be struck in Addis is more difficult than previous financing agreements, with many competing demands and a swiftly changing economic context.

This issue brief provides an outline of the process, politics, and policies of financing sustainable development.

The road to Addis

The government of Ethiopia, as the host country, will play a pivotal role in shaping the Addis conference and its outcome, though the precise nature of that role—and Ethiopia’s role in the process leading up to the conference—remain unclear. In many ways, Ethiopia is ideally suited to host a conference on financing inclusive and sustainable development, with enormous gross domestic product, or GDP, growth; one of Africa’s largest social protection programs; and a Climate-Resilient Green Economy Strategy to achieve carbon-neutral middle-income country status by 2025.

The Intergovernmental Committee of Experts on Sustainable Development Financing has issued its report, which establishes the empirical foundation for the conference’s outcome document and outlines policy options that could be developed into the financing deal that will underpin the post-2015 agenda. Nongovernmental organizations and other groups, such as the World Economic Forum, have issued reports on financing and the post-2015 agenda that will also provide useful background.

The outcome document for the Addis conference will be negotiated in advance, with U.N. diplomats discussing and drafting throughout the winter of 2014 and early spring of 2015 and producing a first draft in February 2015 that will serve as the reference point for negotiations at the conference itself.

Consultations—60 of which have been proposed—will generate additional input on the conference outcome document, with meetings beginning this fall and continuing through January 2015. The Norwegian and Guyanese U.N. ambassadors will facilitate the process and preparations for the conference and aim to balance the interests of developed and developing countries.

The conference itself will be attended by heads of state and ministers of finance, foreign affairs, development, and trade, who will negotiate any changes to the outcome document and then adopt it as the major reference point for international development cooperation going forward.

Conference participation is open to all U.N. member states, specialized agencies, and observers in the U.N. General Assembly. Following the models for openness and participation used in previous international conferences, civil society groups, business actors, and organizations are also invited to attend and to facilitate their own multistakeholder events in both New York and Addis around the summit. The involvement of nongovernmental actors can bolster the ambition of the final outcome and provide a platform to launch of external initiatives that complement and strengthen the intergovernmental agreement.

Although the greater part of the FFD negotiations will take place in New York leading up to the Addis conference, a wider audience—especially national governments—need to be meaningfully engaged for the conference to be a success. Expect to see discussions about post-2015 financing at both the fall and spring annual meetings of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, or IMF; the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos next January; side meetings at the G-20 meeting in Brisbane; and at the G-7 meeting in June 2015. The BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—already referenced the process in the Fortaleza Declaration, which announced the New Development Bank and could play an important role in development financing needs. There will also be a high-level Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, development finance meeting in December 2014 that will focus on ODA.

Timeline for the Financing for Development process

- September 16, 2014: Opening of the 69th session of the U.N. General Assembly.

- October 10–12, 2014: Annual World Bank and International Monetary Fund meetings, Washington, D.C.

- November 15–16, 2014: G-20 Leaders Summit, Brisbane, Australia.

- November 30, 2014: U.N. secretary-general’s synthesis report on the post-2015 development agenda presented to the U.N. General Assembly.

- December 15–16, 2014: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development DAC High-Level Meeting, Paris, France.

- January 21–24, 2015: World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland.

- April 17–19, 2015: 2015 spring meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

- June 4–5, 2015: G-7 Annual Heads of State and Government Meeting, Schloss Elmau, Germany.

- July 13–16, 2015: Financing for development meeting, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- September 15–28, 2015: 70th session of the U.N. General Assembly, New York, New York.

- November 30–December 11, 2015: 21st Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, Paris, France.

- December 2015: 10th World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference.

Sources: General Assembly of the United Nations, “Schedule of General Assembly plenary and related meetings,” available at http://www.un.org/en/ga/info/meetings/68schedule.shtml (last accessed August 2014); International Monetary Fund, “Annual and Spring Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group,” available at https://www.imf.org/external/am/index.htm (last accessed August 2014); Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, “Development Co-operation Directorate (DCD-DAC): Upcoming DAC and related events,” available at http://www.oecd.org/dac/upcomingdacandrelatedevents.htm#dec (last accessed August 2014); World Economic Forum, “Events,” available at http://www.weforum.org/events (last accessed August 2014); Federal Government of Germany “German Presidency 2015”, available at http://www.bundesregierung.de/Webs/Breg/EN/Issues/G8/_node.html (last accessed August 2014); U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, “Calendar,” available at http://unfccc.int/meetings/unfccc_calendar/items/2655.php?year=2015 (last accessed August 2014).

Key issues for negotiators to address

Although the global economy’s recovery from the 2008 crisis has been slow, the outlook for global development is not quite as dire as it may seem. Developing countries continue to grow much faster than developed countries; non-ODA sources of financing, such as foreign direct investment, or FDI, continue to grow; and as a result of implementing the MDGs for the past 15 years, there is more knowledge about how to use development resources wisely.

While the Addis conference is referred to as the “financing for development” conference, money is only part of the story. There are many potential sources of development financing and investment, but the strategies, institutions, and policies that help to increase, improve, and channel funds, align incentives, and drive action toward goals that improve the lives of people and protect the natural environment are equally important.

The Monterrey Consensus provides a good start for the FFD financing discussion. It includes fairly comprehensive coverage of the range of financial flows for development, including domestic financial resources, international public financing, and international trade, and addresses systemic issues. It will need to be updated, however, to reflect the needs of the post-2015 agenda—especially the greater focus on global public goods and jointly tackling economic, social, and environmental challenges.

Improving domestic resource mobilization

Mobilizing domestic resources is the main mechanism for achieving goals at the national level. The good news is that developing countries are growing, and this GDP growth has the potential to generate increased funds for health, education, and other core components of development. But too often, developing countries lack the capacity and systems to collect taxes, reduce tax evasion, and account properly for financing allocations. If growth is to lead to improvements in quality of life, responsible and effective institutions and policies will be required, both domestically and internationally.

Improving domestic resource mobilization has several components that could be discussed in Addis, with actions to be taken by both developed and developing countries. Developed countries can help to get their own houses in order, improving transparency, reducing illicit flows and tax evasion, and ensuring that more revenue stays where it is generated. According to Global Financial Integrity, an estimated $946.7 billion left developing countries in illicit financial outflows during 2011, often ending up in banks in developed countries or tax havens. Initiatives such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, or EITI, and the Dodd-Frank bill are promising attempts to improve transparency and decrease abuse of transfer pricing and other tax-avoidance tactics, but the effectiveness of such initiatives and legislation is still being tested.

Developing countries have work to do, too. Improving the capacity of domestic tax systems can help stem illicit flows and tax avoidance, and development assistance could play a role in shoring up these capacities. Developing countries collect significantly less in taxes as a percentage of GDP than developed countries do and, as a result, tend to be dependent on a narrow tax base, which has economic and political consequences. While high-income countries collect an average of about 35 percent of their GDP in taxes, half of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa collect less than 17 percent. Ensuring that government spending is focused on concrete benefits for citizens is a final challenge, and such a drive for accountability must be domestically driven. A broader tax base and more targeted subsidies can help achieve this objective and should be part of the policy packages discussed for FFD.

Improving development assistance and cooperation

Though domestic resource mobilization is the most powerful financing tool for development, traditional development assistance is the most discussed. Monterrey notably called for developed countries to dedicate 0.7 percent of their gross national income, or GNI, toward official development assistance, a call that is likely to be repeated in Addis. Fulfilling this target is a major concern for developing countries, which point out that only six countries have met this target. Although many others call attention to the dwindling role of ODA, especially in rapidly growing developing countries, it would be a mistake to neglect this central component of financing. Especially for low-income and vulnerable countries and those trapped in cycles of violence, it is difficult or impossible to attract other forms of financing. Yet economic growth and the access to good jobs are key to escaping cycles of poverty, violence, and poor governance and overcoming vulnerability to shocks such as natural disasters and the effects of climate change.

The FFD conference is likely to feature discussions of how to better use aid to accomplish development aims. One emerging solution with the potential to play a larger role in the future is the International Aid Transparency Initiative, or IATI. More than 260 organizations have published data to the IATI standard, including governments, multilaterals, nongovernmental organizations, foundations, and private-sector companies, but it remains to be seen how widely this system is adopted and utilized.

Improving the availability, quality, and transparency of information about where foreign assistance money is spent and its impact is a major issue and has hit some political stumbling blocks. The most complete source of information on development assistance is the OECD Development Assistance Committee, or DAC, which tracks not only ODA, but also other official flows using data from the IMF and nations’ central banks.

Many question whether the DAC systems will work in the new development landscape. DAC is considered to be a rich country club. Its 29 members are all classified as upper income and are required to meet criteria about their development cooperation strategies, institutions, and policies. Yet, increasingly, development cooperation transcends the traditional divide between developed and developing countries. Many middle-income countries, such as China and Brazil, now both give and receive aid, engaging in cooperation with other developing countries in what is called south-south cooperation. Seventeen non-DAC members report aid transactions to DAC on a voluntary basis but most emerging market economies do not, and it appears unlikely that they will. They consider the DAC to be too Western-driven and want to maintain independence over their development assistance and when and how it is monitored.

The lack of a complete and coherent system to track and monitor, however, makes it difficult to assess how much money is being spent on development and whether it is improving people’s lives. Some non-DAC donors are beginning to discuss developing their own system for development cooperation, and this is a good starting point, but much work remains to be done. Creating a clearer picture of the many sources of support available for development, including flows between developing countries, is a necessary part of achieving the ambitious aims of the post-2015 development agenda.

Unlocking climate finance

Perhaps the most difficult question in Addis will be the relationship between climate and development financing. While there is no official number of how much public and private climate finance is currently flowing around the world, the Climate Policy Initiative estimates that public and private climate investments amount to approximately $360 billion per year. The share of public financing provided by developed countries has grown over the past years to between $10 billion and $20 billion annually.

While there is a shared understanding that the current scale of climate finance is insufficient to meet the challenge of climate change and must be increased, developing countries worry that climate financing will compete with development financing or that donors will simply repackage ODA as climate financing. They argue that the two should be kept completely separate to ensure that any climate finance is in fact additional.

In an agenda that integrates economic, social, and environmental issues, however, it is hard to separate climate and poverty challenges on the ground, especially since climate change affects the poor most immediately and severely. Especially in areas such as agriculture and nutrition, water, and energy, climate is inherently linked to development.

It is hard to see how this political impasse can be unlocked, but better and smarter financing will be needed to both tackle poverty and the catastrophic effects of climate change.

New opportunities and challenges

Building on Monterrey, the discussion of resources will need to go beyond business as usual to include not only the more efficient and effective use of current financing flows, but also ways to catalyze additional resources and enable creative problem solving to meet the needs of a more ambitious development agenda.

Private financing

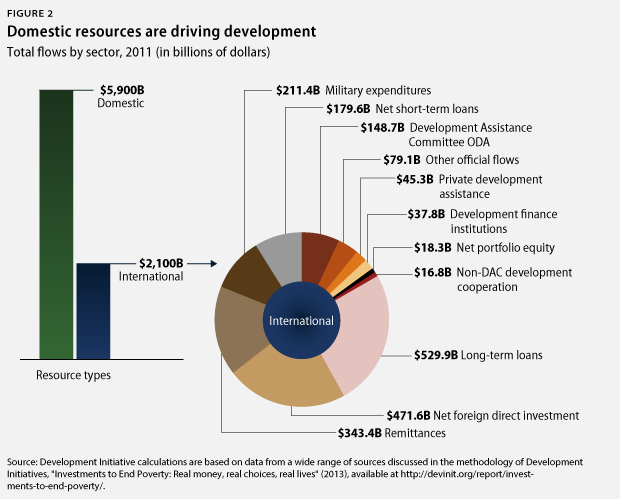

Private financing flows—FDI, equity, and others—were discussed in Monterrey, but have become a much larger part of financing that flows into developing countries in the years since then. Net FDI flows to developing countries reached $471.6 billion in 2011, while ODA and other official flows totaled only $227 billion. In 2012, private flows to developing countries totaled $222.5 billion, while its official development flows amounted to just $150 billion, and many other OECD DAC countries have greater amounts of private flows than official aid flows.

Private flows are potentially more plentiful and more sustainable than concessional grants, but they do not necessarily reap development benefits. The effectiveness of FDI in financing development objectives depends upon how the flows are catalyzed, leveraged, and channeled. More work needs to be done in this area. Public funding is still necessary—the two are complementary in fulfilling development needs. Private finance flows to areas of expected return, and public finance can fill the gap in areas where risk is too high, the returns are hard to monetize—in public goods, for example—or there are asymmetries of information.

Public financing can also serve as an investment or catalyst, attracting private finance for greater development gains. The Global Environment Facility, or GEF, which funds environmental projects such as building agricultural sustainability and developing renewable groundwater resources in arid lands, has provided $12.5 billion in grants since 1991, attracting an additional $58 billion in project co-financing from the private sector. For every $1 of public financing invested, GEF attracted $5 in additional private financing. Imagine if all development assistance were used to catalyze additional financing on the same scale—hundreds of billions of additional dollars could be made available for vital needs such as nutrition, education, basic shelter, and health care.

While the economics are appealing, the politics of private finance are tricky. Many developing countries are suspicious of private-sector involvement, contending that private financing does not replace the need for public financing. On the other hand, many Western countries encourage the inclusion of private-sector flows but are hesitant to include specific recommendations for businesses, in particular reporting on the social and environmental effects of their activities. As a result, the discussion on private-sector financing is likely to be contentious but is worth pursuing anyway. The reality is that private finance will be part of achieving the post-2015 goals, and ensuring that it is channeled and invested wisely and responsibly is an important topic for FFD. Negotiators should not be afraid to have an open conversation with each other and with the business and finance communities about these topics.

The role of middle-income countries

One emerging topic in development financing is the role of middle-income countries, or MICs. Nations with per-capita gross national incomes of more than $1,045 but less than $12,746 are classified as “middle income” by the World Bank, a category that encompasses a wide variety of countries and capabilities, from the BRICS to key regional players such as Turkey and Mexico to populous-but-fragile countries such as Pakistan. Many of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful countries have large numbers of people living in extreme poverty. For example, India, a booming economy and information technology hub, is also home to more than one-third of the world’s extreme poor.

MICs confront a dual challenge: tackling poverty while also growing their economies inclusively and sustainably. With growing middle classes and rapid urbanization, they need to finance extensive investment in power, water, and other development needs. MICs still need to build most of their infrastructure. For example, India still needs to build 70 percent of the infrastructure it will need by 2030, according to global consultancy McKinsey & Company. MICs have the opportunity to leapfrog to low-carbon, sustainable infrastructure. Investment of this kind requires large amounts of upfront financing, and neither ODA nor domestic resources are sufficient to meet this need.

Nonconcessional loans, bilateral export credits, FDI, commercial debt, technical cooperation, and specific regulations and actions to spur market development hold greater promise in tackling MICs’ challenges. A growing focus on infrastructure from the G-20 and the New Development Bank started by the BRICS are initial steps in the right direction. The mechanisms to support MICs’ development are weak, and this nascent conversation deserves much more attention in the post-2015 era, especially given its profound implications for global issues such as resource scarcity and climate change.

Innovative financing

There is much buzz about innovative financing, an ill-defined term that stretches from advanced market commitments to fund medicines to taxing airline tickets with proceeds directed at development. The current discussion on innovative financing is vague and sometimes controversial and will need to be more closely tied to specific recommendations or specific sectors to gain more traction. Successful models can help to breakthrough such negotiation deadlocks. For example, the Pneumococcal Advanced Market Commitment—with funding from the Canadian, Italian, Norwegian, Russian, and U.K. governments and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—has facilitated the rollout of newly developed pneumococcal vaccines, which are generally available only in wealthier countries, to children in low-income countries. Such tools have the potential to help bring together partners and direct funding toward the achievement of post-2015 goals in areas from health to conserving environmental resources.

A political deal?

Although an agreement that takes all of the various sources of development finance into account is crucial, the make-or-break decisions for the post-2015 agenda will come down to highly political topics such as global governance, international trade, technology transfer and intellectual property, migration, and debt relief. Especially for many middle-income countries, these broader issues are more relevant than development financing, which has limited impact for their economies. Additionally, these political issues have a broad consensus among the MICs, compared topics such as south-south cooperation, aid transparency, and their own needs.

If the post-2015 agenda is to live up to its hype as a transformative agenda that moves beyond tackling absolute poverty to put the world on track toward more-inclusive and more-sustainable globalization, these issues are central. At the same time, negotiators will be wary of wading into the waters of other multilateral negotiations, such as those on trade and intellectual property. It remains to be seen how much of a financing deal can be forged at FFD, especially with climate and trade talks yet to come. A good financing deal that offers something to all sides can help build trust, resolve some aspects of these controversial issues, and create space for deals in other areas.

The contours of a political deal are clear—greater influence in the global system for developing countries in return for increased responsibilities. But the details are still muddy. Such a deal is a tall order for a multilateral system that is struggling to make progress on trade, climate, and other areas of international cooperation. And if there is no agreement on development, it is hard to see how progress is possible in other areas. With such high expectations, will the leaders who turn up in Addis rise to the occasion?

Molly Elgin-Cossart is a Senior Fellow with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center for American Progress.

This brief includes substantial contributions from Annie Malknecht, Pete Ogden, and Varad Pande.

The Center for American Progress thanks the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for their support of this brief. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of Center for American Progress and the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The Center for American Progress produces independent research and policy ideas driven by solutions that we believe will create a more equitable and just world.