This column was originally published on MarketWatch.

Friday’s Employment Situation Report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS, wowed with 321,000 jobs added even as the unemployment rate held steady at 5.8 percent. For the past few months, looking under the hood of the report made the labor market seem much stronger than it appeared on the surface. While that trend did not continue, Friday’s report is another data point confirming that the labor market is returning to normal health—and with lots of room to grow.

While Friday’s coverage of the report was overwhelmingly positive, much of the exuberance was because the report so outperformed expectations—the markets only expected the addition of 230,000 new jobs. While the payroll gains were great, the broader measures of the labor market were not nearly as newsworthy. The employment to population ratio was flat in November as was the labor force participation rate, which “has been essentially unchanged since April,” according to the BLS. The overall trend was mirrored in most subgroup figures.

This is not to say there were not some subtle bright spots on hiring. September and October figures were revised upward, adding a total of 44,000 new jobs, and this month marked the 50th consecutive month of employment gains. Another good sign was a fall in the number of underemployed people. According to the report, 177,000 fewer Americans worked part time for economic reasons in November than in October, and that number has decreased by 873,000 individuals over the past year. Finally, the broadest measure of unemployment, U-6, fell for a fifth consecutive month. Over the past year, this measure has fallen from 13.1 percent to 11.4 percent. In other words, the improving health of the labor market is not just a numbers game, it is for real.

Students of macroeconomics should not be too shocked that job gains have been strong this fall. Employment is a lagging indicator of macroeconomic health, so economists would expect improvement in hiring to follow the strong gross domestic product, or GDP, reports for the second and third quarters of 2014. Moreover, there is reason to believe this trend should endure, as leading indicators continue to show a strengthening economy—most strikingly, a run of red hot auto sales this year.

So does all this activity help workers who already have jobs? Maybe. Employment may be a lagging indicator, but wage growth lags even employment. Consequently, it is still too soon to say exactly what is happening in terms of wage growth based on any given month. Two of the best bits of news for workers in this report were significant gains in both hourly wages, up 0.4 percent, and the index of weekly payrolls—the most complete measure of workers’ incomes in the report—which was up 0.9 percent.

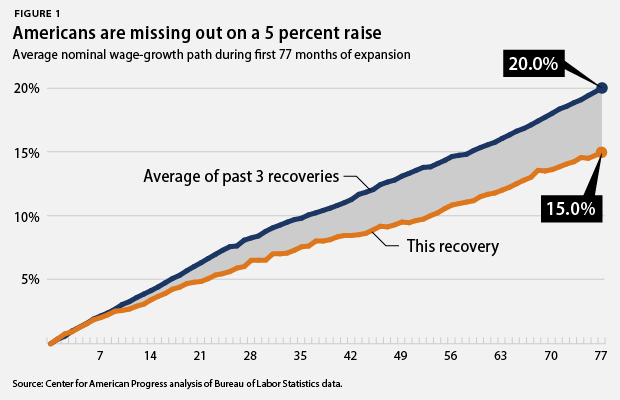

If you look back further, wage gains over the past year were nothing to write home about, but given the sluggishness of income growth in this recovery, the economy can use all the good news it can get on wages. Given the slack in the economy—the many workers who are still on the sidelines—it is hard to predict if this month’s wage gains are just a blip or if wage growth is accelerating and catching up to historical norms. Let’s hope the latter is the case.

Inflation hawks will surely take this report as a sign that monetary policy should be tightened. But between the ground that needs to be made up on wage growth, the millions of additional workers who could rejoin the labor force if wages rise, and falling gas prices, one would have to grasp at a lot of straws to worry about inflation. It is hard to make much of a case that the Federal Reserve should slow this economy down, especially with January’s advent of an even more divided government suggesting that there is little chance of economic help from elected officials in Washington.

Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center for American Progress.