Long before the response to the coronavirus pandemic tanked the nation’s demand for oil and geopolitical spats exacerbated a global oil glut, market analysts were warning that U.S. oil producers were on the verge of falling off a financial cliff.1 After more than a decade of financing their rapidly expanding fracking operations through low-interest loans from Wall Street, oil companies were seeing their access to cheap credit dry up in 2019. “The Next Financial Crisis Lurks Underground,” warned one prescient observer, journalist Bethany McLean, who predicted that the growing credit crisis in the oil business would likely lead to a massive industry crash: “Most things that are economically unsustainable, from money-losing dot-coms to subprime mortgages, eventually come to a bitter end.”2

With shale producers already teetering on the ropes in their fight against a growing credit crisis, the twin fists of the coronavirus-induced demand crunch and the Saudi-Russian price war is leveling the U.S. oil industry with staggering speed.

Now, some in the oil industry are asking for bailouts in any form that Congress or the Trump administration is willing to provide.3 Some policymakers have suggested that oil companies be allowed to drill taxpayer lands without paying royalties.4 Others have proposed that taxpayer money be used to buy oil and take it off the market.5 President Donald Trump has even tasked members of his Cabinet via Twitter to come up with a plan to make funds available to the industry directly.6

Congress should resist the oil and gas industry’s requests for federal bailouts. Throwing taxpayer money at these overleveraged companies would be fiscally irresponsible; bailout dollars would likely flow primarily to debtors, shareholders, and executives, rather than workers.7 Instead of granting even more subsidies to the fossil fuel industry through bailouts, Congress should deliver help to the workers, communities, and states that are now paying the price for the oil and gas industry’s financial recklessness over the past decade. For energy-producing states, the oil bust will add to the pain of the coronavirus crisis by causing a steep decline in expected revenues and job losses, leaving behind a costly trail of abandoned wells and environmental damage.

Congress should deliver immediate assistance to these energy-producing states and counties to help them weather the oil bust, support out-of-work oil and gas workers, and rebuild and diversify their economies in a way that is less dependent on fossil fuels. Out of this crisis, America can and should rebuild a nation that is cleaner, healthier, and more prosperous.

The big buyout

Currently, states that lease fossil fuels on federal lands receive 49 percent of revenues from leasing and developing those resources in their state; the only exception is Alaska, which receives 90 percent. These payments are made in the form of annual disbursements directly to state and, in some cases, county governments.8 With plummeting oil prices and a dramatic scaling back of oil and gas activities, states that are reliant on fossil fuel revenues are almost certain to experience budget shortfalls. Compounded by the larger economic crisis that is slashing tax revenues and overwhelming even the best-prepared rainy day funds, states will be forced to make difficult choices in order to provide health, education, emergency, and other basic services.

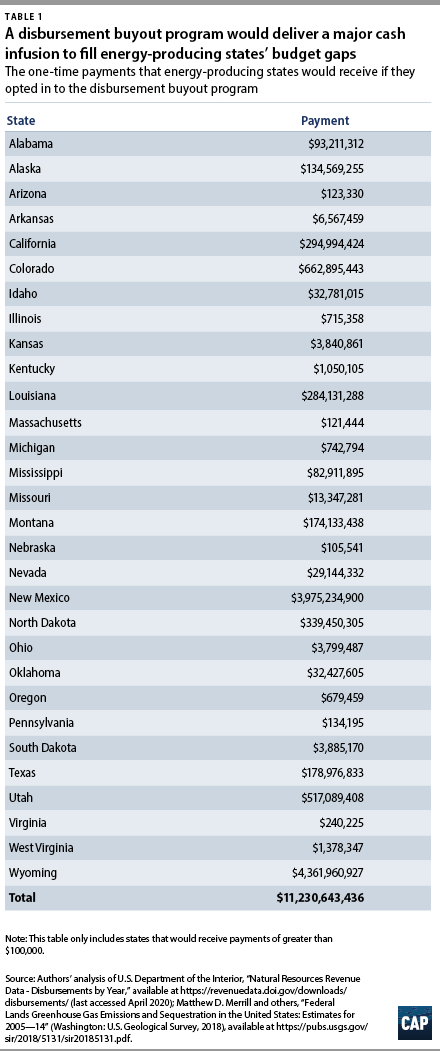

The next stimulus bill should include a disbursement buyout program to offer energy-producing states a major, one-time cash infusion to quickly fill massive budget gaps and make up for diminishing fossil fuel disbursements. The disbursement buyout program would allow states to opt in to a federal buyout of estimated revenues from future oil and gas extraction on public lands in their state over the next 10 years. For states that opted in to the buyout, all future leasing and production revenue on nationally owned public lands in their states would be directed to the federal government.

The lump-sum, advance payout could result in hundreds of millions of dollars for state governments at a time when they desperately need the money to rebuild their economies and invest in local services. Critically, the disbursement buyout program would provide governors an opportunity to extricate their state budgets from unsustainable and unpredictable fossil fuel markets, paving the way for states to expand and diversify their economies.

In tandem with the disbursement buyout program, Congress should put the nation on track to achieve pollution-free public lands by 2030. In line with the nation’s need to transition away from fossil fuels, the disbursement buyout program would assume that public lands achieve net-zero emissions by 2030.9 Payment calculations would start at an average of a state’s past five years of disbursements then ratchet down over the next 10 years following the anticipated decrease in carbon emissions.

If all states opted in to the program, the Center for American Progress calculates that energy-producing states would receive a total of $11.2 billion to meet their immediate budgetary needs. This fund in the federal Treasury would be replenished over the next decade from oil and gas development revenues, including royalties that are no longer split with the states. Congress could also decide to reinvest the revenues in restoration, recreation, or climate resilience projects.

Employing out-of-work oil and gas workers to clean up orphan wells

The oil bust will saddle state, tribal, and federal governments with a growing number of abandoned oil and gas wells without a solvent owner to clean up the mess.10 Hundreds of thousands of these orphan wells are already scattered throughout the country—a dangerous, toxic legacy of prior market crashes and inadequate bonding policies that leaves taxpayers holding the bag for cleanup costs.11 Decaying wells leak methane gas, contaminate groundwater, and are safety hazards for wildlife and communities alike.

Through its next phase of economic stimulus legislation, Congress has an opportunity to address pollution from existing orphan wells in a way that will 1) create thousands of jobs tailor-made for out-of-work oil and gas workers and 2) incentivize state, federal, and tribal governments to modernize and strengthen bonding requirements, heading off an exponential growth of more orphan wells post-oil market crash.12

Congress should create a $2 billion orphan well cleanup fund that states, tribes, and federal land management agencies can access to plug orphan wells and restore affected lands and waters. With approximately 57,000 orphan wells documented on federal, state, tribal, and private lands—and hundreds of thousands more that are undocumented or at-risk of becoming orphaned—CAP estimates that the fund could support 14,000 to 24,000 jobs in energy-producing states.13 And hundreds of additional jobs could be created by bolstering the oil and gas inspections workforce to detect harmful methane leaks and survey orphan wells for cleanup.

Access to the fund should be contingent on demonstration of adequate oversight and bonding requirements that reflect the true and full costs of well cleanup and are indexed to inflation, so that taxpayers are not responsible for remediation on any future oil and gas development.14 Other forward-looking stipulations could include enforcing an existing federal requirement that prevents companies that shirk their reclamation responsibilities from participating in future lease sales—or barring sites reclaimed with this funding from being offered again for oil and gas development.15

Gateway community dividends for counties

The Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program—which works in concert with resource revenue-sharing programs and the Secure Rural Schools program—provides an annual federal payment to local county governments to offset losses in property taxes from tax-exempt federal public lands in their jurisdiction.16 In rural counties where there are high amounts of public land ownership, PILT payments can account for a substantial proportion of a county’s budget for schools, roads, and other public services.17

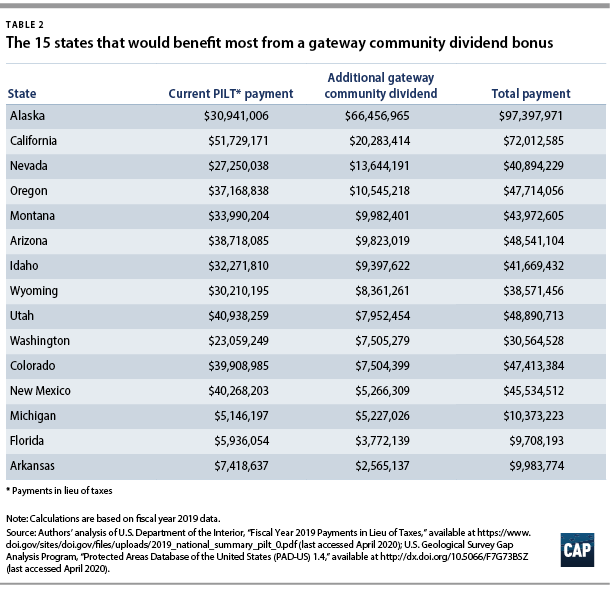

Like states, county governments have been hit hard by the coronavirus response and need help to pay for public services and rebuild their economies—possibly for years to come. This is particularly true for rural counties, where the population’s age tends to be higher than the national average; income is lower; and there are significant health challenges compared with much of the country.18 Although PILT is permanently authorized, Congress has generally funded it for only one year at a time. The lack of consistent, guaranteed funding makes payments unpredictable and long-term budget planning difficult. PILT payments also do not fully compensate counties for the benefits that protected lands provide the country, particularly in gateway communities that require extra infrastructure and services to support tourism and outdoor recreation. The PILT formula’s shortfall tips the scale toward shortsighted decisions—such as drilling and mining activities—that may generate immediate revenue but are bad for the long-term health and resilience of local communities.

Simple improvements to the PILT program to add a “gateway community dividend” for counties could quickly drive more money to counties, support more locally driven protections of public lands and waters, and provide more stable revenues during recessions. The gateway community dividend would tack on to the end of the current PILT formula an added 50 percent premium for every acre of permanently protected public lands. This would provide additional payment to counties that have protected public lands within their jurisdiction, particularly those lands that restrict extractive activity, such as wilderness areas and national parks. In 2019, counties received more than $514 million in PILT payments.19 CAP estimates that this reform would immediately drive $207 million additional dollars to counties annually. Furthermore, 77 percent of these funds would be directed toward rural counties.

The dividend would also rectify the exclusion of acquired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) lands as eligible PILT acres.20 Bringing all FWS lands into the PILT formula would add 4 million more eligible acres to the formula overall.

The gateway community dividend should be paired with the permanent extension and funding of the PILT program to ensure a predictable and sustainable funding stream for counties. Including this policy in a stimulus bill would give county governments—particularly those of rural counties—an increase in money this year and regular, predictable payments going forward that would encourage the protection of some of the country’s most valuable assets.

Conclusion

The oil and gas industry already benefits from an estimated $20.5 billion in U.S. government subsidies and tax breaks annually.21 Rather than offering another bailout to the volatile oil and gas industry—and thereby worsening the climate crisis—Congress should focus on bolstering state and county budgets in energy-producing states, creating new jobs for out-of-work oil and gas workers, and rebuilding clean and sustainable economies.

Kate Kelly is the director of Public Lands at the Center for American Progress. Jenny Rowland-Shea is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Trevor Higgins, Ryan Richards, Will Beaudouin, Christian Rodriguez, Steve Bonitatibus, Sahir Doshi, and Rosemary Cornelius for their contributions to this issue brief.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.

Methodology

Big buyout methodology

To assess the cost of a buyout for each state, CAP calculated the amount of disbursement revenue that states would acquire from 2020 through 2030, assuming drilling and revenues would follow the trend of becoming net-zero by 2030. Using Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) data on annual state disbursements, CAP calculated each state’s average disbursements from 2015 through 2019 to use as the starting payment. It should be noted that the ONRR disbursement data include all mineral disbursements, not just that from fossil fuels, though fossil fuels account for the vast majority—more than 95 percent—of revenues that the federal government collects from energy and mineral activities on federal lands and waters.22

CAP then calculated the estimated annual average greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 2015 through 2018 as 1232 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (MMTCO2e), using data provided by the Wilderness Society, and calculated that an 84.2 percent reduction in GHG emissions would be needed to get to 195 MMTCO2e—the average annual sequestration from 2005 through 2014—by 2030.23 CAP then assumed state disbursements would fall by this same 84.2 percent from 2020 through 2030 and assumed consistent year-to-year reduction in revenues to achieve that reduction.

Orphan well methodology

To calculate the range of jobs, CAP relied on figures from the Canadian government’s recent announcement of an orphan well cleanup fund that equates to approximately seven jobs for every $1 million spent, as well as peer-reviewed job creation estimates for various industries.24 Well-plugging and site remediation require heavy machinery and manpower that resemble construction and repair of gas pipelines, an industry that directly creates 12 jobs for every $1 million spent.25 CAP estimates that a $2 billion fund could cover the cleanup costs of the approximately 57,000 orphan wells documented on federal, state, tribal, and private lands, conservatively assuming that the average cost of well-plugging and basic site restoration is approximately $25,000.26 The fund would begin to absorb costs for more expensive orphan wells and some of the existing, undocumented orphan wells. Of note, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates that reclaiming low-cost wells on federal lands costs approximately $20,000 and that high-cost wells are closer to $145,000.27 The same 2019 GAO report identified an additional 2,300 wells on federal lands “at risk” of becoming orphaned.28 And of the 30 states that reported orphan well data to total approximately 57,000 wells, 21 estimate that there are an additional 210,000 to 746,000 orphan wells that are undocumented on federal, state, tribal and private lands.29 In short, Congress would be well within reason to increase the amount of the orphan well cleanup fund.

Dividend for counties methodology

To calculate the amount that a gateway community dividend would add to annual PILT payments, CAP first aggregated the number of “protected” acres by county using the FWS’ Protected Areas Database of the United States (PAD-US) tracker. CAP defined “protected” as any lands with Gap Analysis Program (GAP) status 1 or 2 that were managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and the U.S. Forest Service.30 The 50 percent premium for protected lands was adapted from an idea that originated with Headwaters Economics.31 Using the per-acre PILT amount from 2019 and applying a 2 million acre ceiling, CAP calculated approximately how much each county would receive if a 50 percent premium were applied to the end of the PILT formula.32 To determine the effect on rural counties, CAP used the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service’s Rural-Urban Continuum index.33