See also: “List of Attacks on American Diplomats and Congressional Responses”

This issue brief contains a correction.

Cleo A. Noel Jr., the U.S. ambassador to Sudan, and his deputy, George Moore, were preparing to leave a reception at the Saudi Embassy in Khartoum when eight gunmen in a Land Rover stormed in to take hostages from among the guests. Within an hour, the attackers had released all but five of the captured diplomats. Two of those remaining were Noel and Moore.

The assailants were members of Black September, a Palestinian terrorist organization closely aligned with Yasser Arafat’s Al Fatah. As negotiations between the U.S. government and the gunmen failed to provide for the diplomats’ release, Ambassador Noel was allowed to call his embassy. When he was told an American representative would arrive that evening to try to move the negotiations forward, he responded, “That will be too late.” Shortly after, Noel, Moore, and a Belgian diplomat were taken to the embassy basement, beaten, and executed by firing squad.

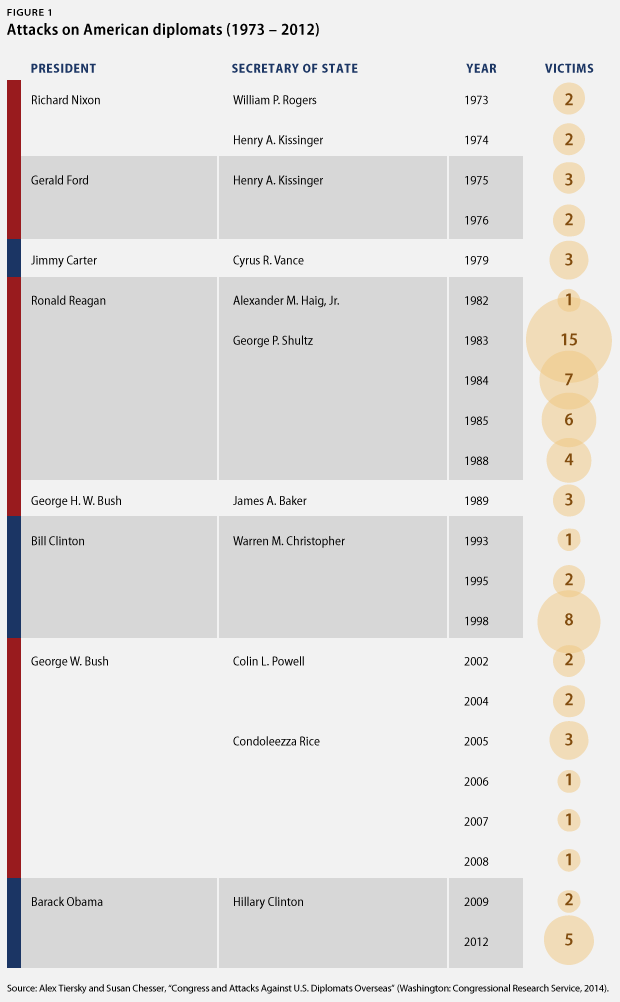

While these events sound eerily similar to the much-publicized deaths of Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans in Benghazi, Libya, in 2012, they in fact occurred 40 years earlier. While many Americans may not realize it, these kinds of attacks have occurred with horrific regularity in recent decades. According to records of the American Foreign Service Association, a total of 76 Americans serving overseas in diplomatic positions have died in 40 separate attacks between 1973 and 2013. This issue brief takes a look at how and why the political response to such tragedies has shifted.

Understanding the focus on Benghazi

The list of fallen diplomats is a potent reminder of the extraordinary risks taken by the men and women who serve this country in embassies and consulates around the world. But it also raises another question: Why has the Benghazi attack received so much attention over the past 21 months, while few people seem to recall little or anything about the previous 39 attacks? Is it that Benghazi stood out so dramatically from the other attacks in terms of the level of violence, the number of deaths, or the damage done to U.S. interests or that security failures may have increased the victims’ vulnerability?

Alternatively, is the focus on Benghazi not the result of anything particularly unique about that attack but instead a measure of how much Congress has changed its approach to dealing with such tragedies? One could argue that the Benghazi attack is similar to or perhaps even less remarkable than many of the preceding attacks in terms of death toll, damage done to national interests, or identified security gaps, and that the explanation for the inordinate amount of attention is largely a matter of fundamental changes in the nature of American politics and the behavior of Congress as an institution.

Record of congressional responses

It seems beyond dispute that this Congress is dealing with the attack in Benghazi differently than previous Congresses dealt with such attacks. Data gathered for a recent Congressional Research Service report quantifies some of the differences.

While Congress and the administration almost certainly had briefings and conversations about all of these attacks, they held no hearings and issued no reports on 25 of the 40 attacks the Congressional Research Service examined. Among the attacks for which no hearings were held was the murder of the ambassador and chargé d’affaires to Sudan described above. Congress held a total of 59 hearings for the remaining 14 attacks; the large majority of these focused on only four attacks. One of these, the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, resulted in 63 deaths—17 U.S. and 36 Lebanese citizens who were employees of the embassy—along with 120 people who were injured. Much of the United States’ Middle East intelligence capability was also destroyed in that bombing, which took the lives of the Central Intelligence Agency’s lead Middle East analyst and Near East director, Robert C. Ames; Beirut Station Chief Kenneth Haas; and six other agency employees. The attack spawned four congressional hearings and one report.

Only six months later, a second attack occurred: the bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks near the Beirut airport. The Congressional Research Service did not include this attack in its analysis, but it arguably could have, since the 238 servicemen who died were on a mission that was as diplomatic in nature as it was military. Caspar Weinberger, the U.S. secretary of defense at the time, said that he pleaded with President Ronald Reagan not to use the Marines as a buffer between the warring Lebanese factions, which he noted had not reached an agreement for either a ceasefire or a pullback of forces. In a 2001 television interview, Weinberger said, “Beirut was an absolutely inevitable outcome of doing what we did, of putting troops in with no mission that could be carried out … So you have a force that was almost a sitting duck.”

The Marines were pulled out of Lebanon three months later, but even more serious concerns about the U.S. government’s ability to protect its foreign emissaries emerged later that year when the U.S Embassy in Lebanon was bombed for the second time in 18 months. Twenty-four people died in the attack, including two American military personnel assigned to the embassy. The response on Capitol Hill was swift. Five days after the attack, a House Appropriations subcommittee held a hearing with senior representatives from the State Department; two weeks after the attack, the House Permanent and Select Committee on Intelligence issued a report on U.S. intelligence performance relative to the bombing. And a few weeks after the release of that report, a delegation from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee issued a second report on the security failures that allowed the attack to occur.

Over the next two years, 14 hearings dealt in some manner with the bombing. Most of these involved examining new and more secure ways to build and protect embassies—and the increased budget requirements such efforts would need. The two Beirut Embassy bombings accounted for 17 of the 65 hearings and reports analyzed by the Congressional Research Service. The 1998 embassy bombings in Nairobi accounted for another eight. To date, the Benghazi incident accounts for 24 of the remaining 40 hearings and reports, and the hearing schedule of the House Select Committee on Benghazi has not yet been announced.

Even though the Benghazi attack accounts for just 5 percent of the American lives lost—and less than 1 percent of the total lives lost—in the attacks on U.S. diplomats over the past four decades, it already accounts for more than 40 percent of the congressional hearings and reports on such attacks.

Tone of the congressional hearings has changed

Even more striking than the comparison of the number of hearings held in response to these past tragedies is a comparison of the hearings’ tenor and content. A number of recent incidents underscore the extraordinary vitriol that has characterized much of Congress’s preoccupation with Benghazi.

One incident revolves around remarks made by Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA), chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, at a Republican fundraiser earlier this year. He charged that senior administration officials not only were derelict in preventing the attack but also that they had deliberately blocked rescue efforts for the victims. Specifically, Rep. Issa suggested then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had ordered the director of the CIA to “stand down” from efforts to rescue Ambassador Stevens. This remarkable allegation came only weeks after the Senate Intelligence Committee issued a bipartisan report repudiating it: “The Committee has reviewed the allegations that U.S. personnel, including in the IC [intelligence community] or DoD, prevented the mounting of any military relief effort during the attacks, but the Committee has not found any of these allegations to be substantiated.”

One might compare Rep. Issa’s allegations with Associated Press reporting following the second bombing of the Beirut Embassy in September 1984. The essence of AP’s story was that Reagan administration witnesses testified before a Senate committee and “faced sharp questioning.” The sharp questioning, however, was an expression of bipartisan dismay that the administration was requesting only one-third of the funding amount that its own analysis indicated was necessary to enhance embassy security. Then-Sen. Joe Biden (D-DE) asked, “Why should we not be doing whatever is necessary as fast as possible?” Sen. Charles “Mac” Mathias (R-MD) agreed. “If there are some false economies here that will affect our security program,” he said, “we want to know about them and we will make our own judgment about them.”

There were some incidents in which real acrimony surfaced. In the week following the second Beirut Embassy bombing, President Reagan made an extemporaneous comment about “the near destruction of our intelligence capability in recent years before we came here.” That remark caused a firestorm in the Senate after the press interpreted it as an attempt to blame his predecessor, Jimmy Carter, for the bombings. But the president dissociated himself from that interpretation, telling reporters, “I will answer your questions about the way you have distorted my remarks about the CIA.” Vice President George H.W. Bush went further, stating that President Reagan was not trying to imply that the Carter administration was responsible for the bombing.

Generally, the gentility displayed in these hearings is impressive. There was nearly always a friendly, respectful rapport between the members of the various committees, as well as between the committees and executive branch witnesses that testified before them. In a March 2000 hearing that dealt in part with the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, then-President Bill Clinton’s secretary of state and members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee sounded more like old friends sitting around a living room than adversaries out to undermine each another. Committee Chairman Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC), widely considered the arch conservative of Congress, welcomed the secretary:

By my count this is your 16th appearance before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and it has always been a pleasure to have you with us. And while we have not always agreed on the multitude of matters confronting the nation during your tenure, we have accomplished a great deal together … It has been a pleasure and a privilege to work with you, and the Committee is honored to welcome you here this morning.

Another example of the largely bipartisan nature of previous congressional inquiries on this subject was the House Appropriations Subcommittee hearing that occurred only days after the second bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut. It dealt with funding for embassy security. Despite the intense frustration expressed by members of both political parties over the security lapses that had permitted the bombing, the transcript of the hearing shows little difference between the kinds of questions being asked by Democratic members and those being asked by their Republican counterparts. There were no comments or questions that asserted the deaths resulted from malfeasance or misconduct.

With the exception of the spat around President Reagan’s comments, there was no finger pointing, nor were there any attempts to use these tragedies as an opportunity to document culpability among political opponents. The same cannot be said about the political reaction to the Benghazi attack.

Security issues surrounding pre-Benghazi attacks were serious

Clearly, the Nixon administration was caught flatfooted by the attack in Khartoum. Twenty years after the attack, Paul A. Jureidini wrote in The Middle East Quarterly, “US intelligence on Fatah/BSO (Black September) in 1973 was poor to non-existent.” Earlier in the Nixon administration, senior intelligence operatives had blown a promising opportunity to establish contact at high levels within Fatah and had not managed in the four years since to develop a replacement. There was simply no capacity to anticipate such attacks, dissuade Fatah or Black September from carrying them out, or know how to negotiate on behalf of hostages.

While President Nixon had appointed a cabinet committee nominally tasked with developing policies to combat terrorism, the committee was not staffed at the time of the Khartoum attack. The largest and perhaps most definitive work on the attack is a book titled Assassination in Khartoum, written by David Korn for the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy. Korn argues:

The creation of the cabinet committee made it sound as though the Nixon administration were gearing up for a high-powered campaign against terrorism … Nothing could have been further from the truth. Meyer [Armin Meyer, a senior Foreign Service officer who had been put in charge of the committee] himself quickly learned that he was to be a general without an army. He was responsible for coordinating everything … but the entire staff under his direct orders consisted of one middle-grade officer and one secretary.

One of Meyer’s tasks was to establish a policy to deal with hostage situations. According to Jureidini, Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s national security advisor, advocated a policy “of no negotiations, no deals, and no concessions, but without debate or study of this policy’s implications.” This was a deviation from previous policy in which the United States had, as recently as 1969 and under the leadership of the Nixon administration, ransomed U.S. Ambassador to Brazil Charles Elbrick. Korn argues that Kissinger’s advocacy of this policy was based on the mistaken perception that Israel followed it. According to Korn, Israel “loudly proclaimed a policy of refusing to pay ransom” but “never deliberately sacrificed anyone to the principle of ‘no deals’ or ‘no ransom.’”

The Kissinger proposal was also contrary to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s strategy, which was, according to Jureidini, “do everything to save lives and then go after the perpetrators.” Meyer, who was tasked with developing a consensus in the Nixon administration around this policy, found that neither Secretary of State William Rogers, nor any other senior political appointee, would sign on to it.

Not only was the administration’s attempt to develop a policy awkward, but its implementation of the strategy it did choose to pursue was awkward as well. It took nearly five hours for the State Department to reach the decision to send a negotiating party—led by Deputy Undersecretary of State William Macomber—to Khartoum. Macomber, however, was unable to get the Air Force to provide a plane. He finally turned to the White House for assistance, but when the delegation finally arrived at Andrews Air Force Base, no plane was available. After further consultations with the White House, Air Force One was eventually made available to fly the delegation to New Jersey, where they boarded a C-141 aircraft that did not have sufficient fuel capacity to reach Sudan without stopping in Germany. The plane was not only very slow but also lacked the communications capability such a party needed. It was also so noisy that it was difficult for the delegation to even talk during the flight.

Another key issue was the U.S. government’s public pronouncements while the two American diplomats were being held hostage. According to Korn, Meyer advised both the State Department and the White House that all spokespersons “should decline comment. The situation was just too delicate to take any chances. People’s lives are at stake.” He also pointed out that, “The fact that Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir had just been in Washington made it particularly important … that the president say nothing. Any suggestion that the United States was coordinating with Israel could precipitate the killing of the hostages.”

While Secretary Rogers followed that script closely when responding to press questions, President Nixon did not. At an 11:30 a.m. press conference, he responded to one of the first questions by saying:

Last night I was sitting by the wife of Mr. Rabin (Yitzhak Rabin, ambassador of Israel to the United States) and we were saying that the position of ambassador once so greatly sought after, now in many places … becomes quite dangerous. As far as the United States as a government giving in to blackmail demands, we cannot do so.

In less than three hours, the two Americans were dead.

Not only did the United States fail to follow the first part of the approach used by its lead domestic law enforcement agency—do everything to save lives—but it also utterly failed to follow the second part of the approach, which was to “go after the perpetrators.” The administration called for the death penalty for the eight attackers, but the Sudanese Court sentenced them to life in prison. The Sudanese president commuted those sentences within hours to only seven years. The gunmen were then sent to Egypt to serve their sentences, where three of them promptly disappeared.

Jureidini summarized the situation in the following way:

For all these reasons, no one in the U.S. government seemed to be in a position to determine how it should respond to the siege of the Saudi embassy and the hostages, leaving it to the Sudanese to deal with the problem on their own, without guidance. Washington seemed to hope that the terrorists would give up on their own as they had done in 1972, at the Israeli embassy in Bangkok …

But the Democrats, with a solid hold on both congressional houses, chose to let the Nixon administration and the State Department sort through these problems and find their own solutions. After all, they had the greatest stake in making sure that the ambassadors charged with carrying out their policies lived to succeed in their missions. The opportunities to castigate the Reagan administration over its repeated security lapses in Lebanon during the early and mid-1980s seem all too obvious. As Jane Mayer, a Wall Street Journal reporter based in Beirut in 1983 wrote in a recent article for The New Yorker:

There were more than enough opportunities to lay blame for the horrific losses at high U.S. officials’ feet. But unlike today’s Congress, congressmen did not talk of impeaching Ronald Reagan, who was then President, nor were any subpoenas sent to cabinet members. This was true even though then, as now, the opposition party controlled the majority in the House.

Bomb making in Beirut had been evolving as a cottage industry for more than a decade before the attack on the U.S. Embassy in March 1983. Car bombings were used with increasing frequency by various Lebanese militias over that period, and it is hard to imagine that anyone charged with thinking about the security of the U.S. Embassy in Lebanon would not have concluded years before the first bombing that the embassy could not be effectively protected by anything less than the construction of a walled perimeter that could be entered only through carefully controlled gates.

The failure to take such steps to protect the first embassy was difficult to explain. The fact that President Reagan sent Marines to occupy an indefensible terrain in a nation with 27 warring militias—and with rules of engagement that did not allow guards to keep ammunition in the chamber of their weapons—was unforgivable. But the failure to protect the second embassy once it was occupied seemed to border on the absurd. Nonetheless, Congress’s response to these mistakes was measured, and discussions focused not on who to blame but instead on how the problem could be fixed.

Why were the responses of previous Congresses so different?

Members of Congress have always been obliged to play two separate and often conflicting roles. One is to keep the messages of their political parties in the public consciousness. The second is to serve the public interest regardless of partisan dictates. There are certain issues on which members find it easy to side with their parties. For example, it is easy to be critical of opponents’ use of public office to perform favors for their contributors or allies. But there are other issues on which members of earlier Congresses were delighted to break with the party line in order to show their constituents back home that they kept their own council and to appeal to and cultivate a national audience based on their statesmanship. Former Sen. Arthur Vandenberg’s (R-MI) notion that “politics stops at the water’s edge” was never truly a norm in the United States, but it was far more the norm for most of the period following World War II than it is today. In particular, only recently have politicians been willing to use the all-too-frequent deaths of those who serve our country in the most dangerous parts of the world for blatant partisan messaging.

This loss of restraint has implications beyond the fact that it is distasteful. Excessive partisanship makes the fact finding that should occur in the wake of such events far more difficult. Those who have firsthand knowledge of events are less likely to cooperate and more likely to be highly guarded in their comments. Small yet potentially consequential policy course corrections are often overlooked in favor of grand indictments. Opportunities to work cooperatively to find policies that will ensure greater protection—such as the program to modify or replace embassies in high-risk portions of the world—are compromised.

It would be a fitting memorial to Ambassador Stevens and the three other Americans who died in Benghazi if we could learn again to deal with these incidents in a less partisan, more public-spirited manner.

Scott Lilly is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.

*Correction, September 16, 2014: This brief has been corrected to reflect the type of aircraft

that carried the Nixon administration negotiating party from New Jersey to Sudan, with a

stop to refuel in Germany.