Instruments for pricing carbon are beginning to proliferate. In recent years, South Korea implemented a trading system; France and Portugal implemented carbon taxes; China began seven subnational trading system pilots and announced a national trading system for implementation by 2020; and South Africa and Chile announced carbon taxes that will take effect in 2016 and 2017, respectively. These developments augment a landscape of carbon pricing instruments that are already well-established in various countries and regions, including the European Union, Japan, New Zealand, and the Nordic countries.

What is carbon pricing?

Carbon pollution results in significant costs to society through the damage caused by climate change. This includes damage to health, agriculture, regional security, economies, livelihoods, and ecosystems. To “price carbon” means to implement a policy tool that helps transfer those costs from society to the carbon polluter, which drives emissions reductions.

The primary approaches to carbon pricing are carbon taxes and emissions trading systems. Carbon taxes can be applied to the amount of carbon contained in fuels, for example, or to the tons of greenhouse gases emitted. Emissions trading systems establish a cap on emissions and set a certain number of emissions permits, which are able to be bought and sold. In either system, polluters have the option of reducing emissions or covering the associated cost.

Pricing carbon is a simple, effective, and efficient tool for driving the emissions reductions necessary to address climate change. Moreover, integrating carbon pricing systems in different regions—known as linking—can lead to a number of benefits. Integration can bring price stability, for example, and can enhance cost effectiveness by increasing the options for emissions reductions. It also can serve as a signal to investors that governments have a common commitment to a low-carbon future.

The national governments of the United States, Mexico, and Canada are newly aligned in their dedication to address climate change. The leaders of these nations therefore have a political opportunity to work toward a North American carbon price, which would significantly propel the global movement to price carbon. In the coming months, the three heads of state will meet for the North American Leaders’ Summit—a venue that could serve as a forum to explore the establishment of a pricing system that spans the continent.

An opportunity for North American cooperation

For the first time, the major economies of North America—the United States, Mexico, and Canada—are simultaneously eager to display ambition and leadership with respect to international climate cooperation. Mexico was among the first countries—and was the first developing country—to formally submit its national climate targets for the recent global climate agreement, which was finalized in Paris in December 2015. Canada, in a significant reversal compared with the era of the Harper administration, is now pursuing constructive climate partnerships, as demonstrated in the recent U.S.-Canada pledge to cut methane emissions from the oil and gas sector. The United States, for its part, can claim significant responsibility for fostering the global political will that was necessary for the Paris agreement through its climate diplomacy with major emerging economies, such as China and Brazil, and through its leadership in putting forward an ambitious national target.

In this window of political alignment on climate change, one of the potential trilateral collaborations that the nations should explore is an initiative to develop a North American carbon price. The forthcoming North American Leaders’ Summit, which is not yet announced but is likely to be held later this year, could serve as a forum for discussions.

A commitment to pursue a system that has at least subnational participation—that is, at the state or province level—from the United States, Mexico, and Canada would be a first step toward a comprehensive North American carbon price and would provide momentum to the burgeoning effort to price carbon globally.

The current state of North American carbon pricing

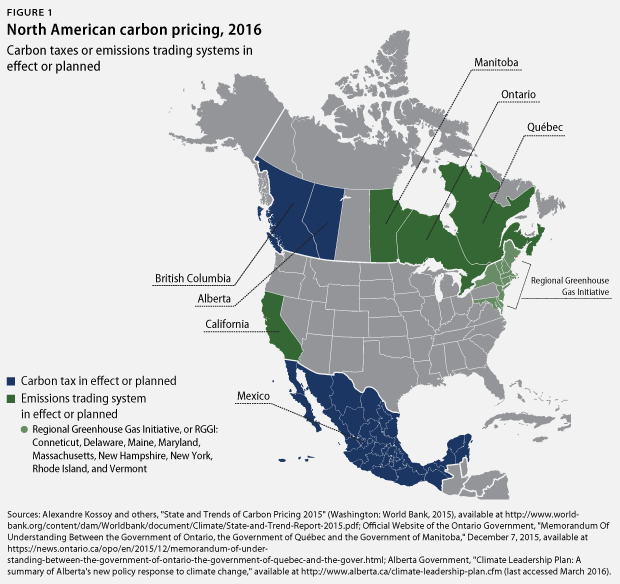

National or subnational pricing systems are already in effect across the continent, providing an existing base upon which to build a North American price on carbon. Quebec and California have well-established trading systems, which linked in 2014 such that emissions allowances can be traded throughout the two regions. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic United States, nine states participate in a trading system called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI. Meanwhile, Mexico and British Columbia have carbon taxes.

Further carbon pricing developments—and linkages among pricing instruments—are forthcoming. In December, Ontario and Manitoba signed a memorandum of understanding that documented their intention to implement trading systems linked to those of Quebec and California. In November 2015, Alberta announced a carbon tax that will take effect in 2017.

Possible paths forward

During Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s recent visit to the United States, he and President Barack Obama announced several bilateral initiatives that could serve as foundational steps for trilateral action and the ultimate establishment of a North American pricing policy. The leaders pledged, for example, to align the nations’ approaches to analyzing the societal costs of carbon pollution and the benefits of taking action. They also pledged to promote carbon markets in the context of the Paris agreement and committed to “expand their collaboration in this area over time.”

There are a number of possible models for creating a pricing instrument that has at least subnational participation across North America. For example, the countries could—following the lead of Mexico, British Columbia, and Alberta—promote the adoption of a tax. In the United States, there are signs that the establishment of a carbon tax could, ultimately, gain bipartisan support.

Alternatively, the countries could promote subnational or national participation in linked trading systems. Mexico has indicated interest in developing a trading system and has underlined the importance of international pricing instruments in its climate goals submitted for the Paris agreement. It is also notable that Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard signed an agreement in 2015 that included knowledge sharing with respect to carbon pricing in Quebec. It is therefore conceivable that Mexico could join the system that is set to span California, Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba.

A third option for a continental pricing instrument is a hybrid: Given that carbon taxes can be designed to allow tradable offsets for compliance, it is possible for carbon tax and emissions trading systems to be linked. It therefore would be possible to link the system in Mexico, which launched a trading platform for offsets in 2013, with the California-Quebec nexus—either as an end in itself or as a first step as the carbon tax in Mexico evolves into an emissions trading system. Mexico’s undersecretary for environmental policy and planning, Rodolfo Lacy, already has suggested the possibility of exporting offsets. Interactions between national and subnational policies—especially as they relate to offsets—would need to be closely scrutinized to avoid unanticipated impacts and ensure the integrity of the overall system.

With the assortment of carbon pricing instruments already established in North America, it is worth noting that the emergence of an integrated pricing system would not by necessity displace existing systems. It is possible for taxes and emissions trading systems to coexist—as they do in many parts of the world, including France and Sweden—with a tax serving as a price floor, for example, or with the two instruments targeting different sectors. In Canada, Prime Minister Trudeau is pursuing a national policy that would establish a hybrid system and bring consistency to carbon prices across the provinces.

Developing a particular pricing mechanism that has the ability to engage each of the three countries will pose policy, political, and practical challenges. Overcoming those challenges will involve careful consideration of the strengths and weaknesses of each approach as they relate to the status quo.

Conclusion

As temperature records continue to be broken, it is clear that the world must act quickly to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Working toward a North American carbon pricing approach would be a major contribution to addressing the climate challenge successfully and would be particularly notable given participation from both developed and developing countries. Because a North American price on carbon will be difficult to achieve, it is essential that technical experts from each country begin a collaboration in 2016.

Gwynne Taraska is the Associate Director of Energy Policy at the Center for American Progress. Greg Dotson is the Vice President for Energy Policy at the Center. The authors would like to thank Ori Gutin, an intern with the Energy Policy team at the Center, for research on Figure 1.