The federal coal program has long been a blind spot in U.S. climate policy. A 2015 study commissioned by the Center for American Progress and The Wilderness Society found that fossil fuels extracted from federal lands and waters account for one-fifth of all energy-related greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Of those emissions, nearly 60 percent come from mining and burning coal from taxpayer-owned public lands.

The United States cannot meet its goals of cutting greenhouse gas emissions and accelerating the production of cleaner energy sources without structural reforms to the federal coal program. Federal coal, 90 percent of which is produced in the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana, is made available to coal companies through a noncompetitive process at below-market rates. As a result, undervalued federal coal helps drive down the price of coal nationally. This distortion of U.S. energy markets works against the country’s transition to clean and affordable alternative energy sources.

In early 2016, the Obama administration acknowledged the need to overhaul the federal coal program. “I’m going to push to change the way we manage our oil and coal resources, so that they better reflect the costs they impose on taxpayers and our planet,” President Barack Obama said in his final State of the Union address. Days later, Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell issued Secretarial Order No. 3338, directing the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, to temporarily stop selling new coal leases until a comprehensive Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement, or PEIS, is completed.

As part of this PEIS process, policymakers will be faced with the challenge of developing a new framework for the federal coal program that better meets the United States’ near- and long-term energy, climate, and economic goals; addresses the economic and environmental concerns of coal-dependent communities as the United States transitions to cleaner energy sources; and garners sufficient political support to be stable, enduring, and effective for many years to come.

Although stakeholders in the federal coal program have already brought forward several ideas for the U.S. Department of the Interior, or DOI, to consider, the most prominent proposals do not adequately meet all the objectives outlined above.

- Preserving the status quo, which the coal industry is fiercely defending, would undercut the United States’ ability to cut greenhouse gas emissions, impede the advancement of cleaner and renewable energy sources, and continue to saddle taxpayers with the costs of the industry’s pollution.

- Some, including the White House Council of Economic Advisers, have suggested incorporating the social cost of carbon—an estimate of the economic damages associated with 1 ton of carbon dioxide emissions—into the royalty rate that coal companies pay on each ton of coal mined. This approach would deliver increased revenues for coal-dependent states and local governments and provide a market-driven approach to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. On the other hand, increasing the federal royalty rate to a level that is several times the cost of the commodity itself would be highly controversial and vulnerable to immediate congressional repeal. These things could promote use of other coal sources.

- Some stakeholders, led in part by Greenpeace, have proposed immediately ending all future coal leasing on public lands. If implemented, this proposal would achieve significant carbon emissions reductions as reserves on existing leases are depleted and production from federal mines declines over the coming decades. To be successful and enduring, however, this approach would need to build additional public and political support and address concerns from affected coal-dependent communities.

- More targeted reform proposals, including ending the practice of self-bonding—in which some states allow coal companies to put up their own good name and overall financial health as collateral, instead of surety bonds for reclamation liabilities—strengthening reclamation requirements, and bringing coal royalty rates in line with the offshore oil and gas royalty rate are vitally needed and should be implemented. These changes alone, however, will not bring the federal coal program in line with the United States’ greenhouse gas reduction targets.

This issue brief proposes a structural reform that would help the federal coal program meet U.S. climate and energy goals, support economic transition in coal-dependent communities, and be more likely to survive political and legal challenge. Specifically, CAP is proposing a credit auction that would restore competition to the federal coal program by allowing eligible companies to bid on a pool of carbon credits that will give them the right to mine a certain volume of coal on federal lands. The amount of carbon credits the federal government sells would be determined through a five-year public planning process that would be modeled on the federal government’s offshore oil and gas program. Over time, the amount of credits offered at auction to exceed minimum bids set by regulation—either as is currently stated in the federal regulation on fair market value and maximum economic recovery for the federal coal leasing program, 43 C.F.R. § 3422.1(c)(2), or updated through the public process—would be reduced and likely phased out to meet U.S. climate goals. This reformed coal leasing system would give states with federal coal resources additional time and resources to diversify their economies during the nation’s shift toward cleaner, more abundant renewable energy supplies.

The federal coal leasing program is broken

To develop a new structure for the federal coal leasing program, it is important to understand why and how the current structure is falling short. Over the past decade, these failures have been well-documented by investigators from the Government Accountability Office, or GAO; the Department of the Interior Office of Inspector General, or OIG; and Congress. In general, these investigators have concluded that the coal leasing process is dictated by the coal industry, fails to deliver a fair return to taxpayers, and facilitates the nearly unlimited sale of federal coal resources at a very low cost.

The current leasing system is structurally flawed and inherently noncompetitive

Of the dozens of problems that independent investigators have identified, two in particular are having oversized, negative consequences for taxpayers, local communities, and the environment.

First, the federal coal leasing program discourages competition that would drive up prices, increase returns to taxpayers, and balance production levels. Notably, federal coal production—and resulting greenhouse gas emissions—has risen dramatically in recent decades, while competition among companies declined in that period. In the Powder River Basin, for example—home to nearly 90 percent of all federal coal—coal production grew 150 percent between 1990 and 2010, while the number of mining companies in the region declined from 12 to 7. As noted by the DOI OIG in 2013, “a competitive market generally does not exist for coal leases.”

The lack of competition in the federal coal program stems from the structure of the leasing process itself. Two procedures exist for leasing federal coal, but only one has been used consistently. Decades ago, the BLM stopped selecting and offering tracts for auction within a defined coal-producing region and instead began relying solely on the lease-by-application procedure wherein a company proposes a tract for lease. The BLM claims that, “for decades the demand for new coal leasing has been associated with the extension of existing mining operation on authorized federal coal leases, so all current leasing is done by application.”

As a result, firms are able to select and apply for tracts that are exceedingly unlikely to attract competition—namely, those that are adjacent to their own existing mines. Such tracts require small startup costs for the owner of the nearby mine but would be relatively expensive for a competing company to mine. A firm can also skip the bidding process altogether by proposing a small nearby tract—less than 960 acres—as a modification to an existing lease.

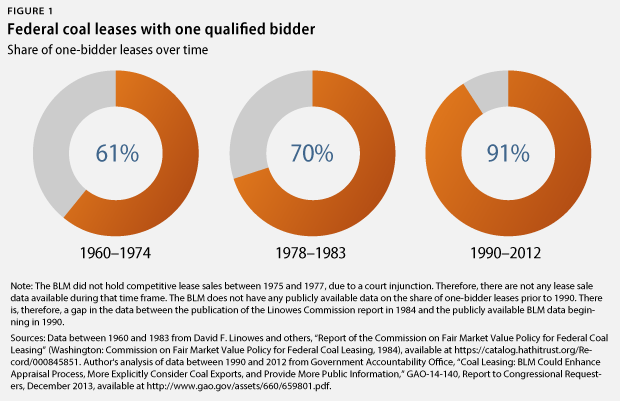

These factors, along with market conditions, have led to the decrease in the number of bids the BLM receives on a given lease. In the 1960s and early 1970s, 61 percent of leases had only one bidder, while 18 percent of leases had three or more bidders. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the BLM auctioned leases, the proportion of one-bid leases rose to 70 percent. Since 1990, however, nearly all leases—91 percent—have been one-bid leases, and only 1 percent have attracted three or more bidders.

Estimates of the extent to which taxpayers have been shortchanged due to the noncompetitive nature of the leasing process range from the millions of dollars to the tens of billions of dollars before fully considering environmental and public heath costs.

Determining a true fair market value is critical to ensuring a fair return to taxpayers

The absence of competition in the coal leasing process gives rise to a second major structural problem in the program: the Bureau of Land Management’s process for determining a fair market value, or FMV, for coal. The agency’s decisions about what price it will accept for the purchase of taxpayer-owned coal have had a downward impact on coal prices nationally and have been a factor in the coal industry’s decision to shift production from private lands toward federal lands, primarily in the Powder River Basin.

The question of what price the federal government should accept for the purchase of coal is not new. Congress mandated the 1983–1984 Commission on Fair Market Value Policy for Federal Coal Leasing, known as the Linowes Commission, to give guidance to the Department of the Interior in the absence of any congressional definition of fair market value. The commission—comprised of public policy, economic, legal, and financial experts—made recommendations that were echoed decades later by the Government Accountability Office and the DOI Office of Inspector General. These recommendations include increasing transparency, welcoming independent oversight of the appraisal process, and creating a separate definition of FMV for noncompetitive lease tracts.

The BLM took steps to address these concerns following the release of the 2013 GAO and OIG reports. The bureau updated its guidance on FMV procedures; required additional information, including third-party review and consideration of export markets; and somewhat increased its transparency without wholly disclosing the calculations behind the FMV determined for specific leases. The BLM’s Coal Evaluation Handbook now states that, “It is not acceptable to redact an entire document” and that “consideration should be given to timely posting [of] public versions of FMV related documents.” The GAO and OIG reports also raised concerns about the practice of accepting bids that are below the BLM’s presale FMV estimate. But the FMV-determination process for new and modified leases remains murky, and there is ample evidence that federal coal leases are still being routinely undervalued.

Given the absence of competition in the leasing program, it is imperative for the BLM to ensure that a true FMV is met or exceeded for each leased mining tract. In North Dakota, however, all of the one-time payments—known as bonus bids—that mining companies make to lease a parcel of land for coal extraction were for $100 per acre between 1990 and 2012. Regulation set this amount as a floor for bonus bids in 1982. Accounting only for inflation would bring the floor up to $247 per acre. Wyoming saw the greatest increase in bonus bids since 1990 when compared with other states with federal coal reserves, but the bids still amount to less than $1.38 per ton of coal. It’s impossible to assess the BLM’s analyses that led to the FMV price points behind these bids because the data are not publicly available. But the DOI IOG warns that “even a 1-cent-per-ton undervaluation in the fair market value calculation for a sale can result in millions of dollars in lost revenues.”

The BLM could achieve a better return for taxpayers by soliciting bonus bids on a group of leases instead of through the case-by-case way that leases by application are currently considered. The Linowes Commission recommended a leasing structure called “intertract bidding” through which the BLM would pit a number of bids against each other even when the bids are not on the same tract. The commission argued that through intertract bidding, the BLM could better mimic free market competition by allowing coal companies to bid simultaneously on separate tracts of land. BLM would then compare the bids on those tracts on the basis of dollars offered per extractable energy output, measured in British thermal units, or Btu, of the coal available on the land. Alternatively, the bids could be compared on a dollars-per-ton-of-coal basis.

The BLM attempted to implement intertract bidding through a pilot program in the Powder River Basin in 1982, but the project did not get off the ground because the agency could not obtain surface mining rights. Within a decade, the BLM decertified the Powder River Basin as a coal region, and the intertract bidding method for leasing was shelved. Since then, the Powder River Basin has become a major coal producer, with 90 percent of all coal mined on federal lands coming from the region.

Lessees have shortchanged taxpayers and coal communities

Many of the largest players in the coal industry—including Alpha Natural Resources, Arch Coal, and Peabody Energy—have filed for bankruptcy in the past year. Due to permissive state policies that allowed companies to put up little outside collateral beyond their own financial health, taxpayers are left with the expenses of cleaning up environmental damages when companies go bankrupt and are no longer able to cover the costs.

Coal companies have also shortchanged mine workers. For instance, a subsidiary of Peabody Coal, Patriot Coal, filed for bankruptcy in 2013 just after assuming the burden of all of Peabody’s worker benefits, which totaled $1.3 billion. The bankruptcy proceedings reduced that responsibility to only $400 million. That same year, Patriot Coal paid its executives $6.9 million in bonuses.

As the Bureau of Land Management reassesses the federal coal program, it has the opportunity to better safeguard coal communities and taxpayers against similar environmental and financial burdens in the future. The BLM should implement stricter standards that bidders must exceed to ensure that they will fully meet their obligations to mine workers, coal communities, and taxpayers.

Recommendations: A 5-year plan with coal leasing limits, credit auctions, and bidder integrity standards

While the Bureau of Land Management has previously considered leases within a given region, in the context of climate change, the bureau needs to address the total impact of leasing across all public lands in order to account fully for environmental and public health. However, the BLM’s lease-by-lease consideration of the current lease-by-application process enables the agency to assess only the potential environmental impacts of mining on the land parcel being proposed for lease. The process does not easily permit the BLM to evaluate whether the amount or quality of coal being sold is consistent with U.S. energy and climate goals. It also does not enable the agency to assess a company’s history of environmental reclamation or its relative financial stability.

Both the intertract bidding process proposed by the Linowes Commission and the Department of the Interior’s five-year program for offshore oil and gas leasing could serve as templates on which to build a more effective, responsive, and transparent coal leasing program. The DOI can and should establish clear bidder integrity standards to ensure that coal companies that wish to mine on federal lands meet high standards for environmental and worker protection.

The credit auction

The BLM has broad authority to decide how much coal it should sell and where that coal should be mined. CAP proposes that the BLM implement a credit-based version of intertract bidding that sets a limit on the amount of coal that is sold. Rather than hosting a lease sale with multiple tracts up for simultaneous bid, the BLM should allow bidders to bid on a fixed amount of mining credits. The winning bidders would gain the right to mine a certain amount of coal. These bidders would then submit applications for the specific tracts of land on which they would like to use their credits to mine the coal. This process would allow the BLM to better prioritize the fairest return available to taxpayers while allocating credits up to a preset cap. The BLM should only offer credits to bidders who meet predetermined standards of reclamation, financial stability, and worker safety and compensation.

Setting the cap

- The BLM should set an overall cap on total federal coal tonnage leased in a five-year period in line with overall U.S. climate goals.

- The BLM should consider variations in the emissions associated with different types of coal mined on public lands when setting the cap.

- The BLM should ramp down the cap over time to adhere to U.S. emissions reduction plans.

The BLM should offer an amount of publicly owned coal for auction that, when burned, would be responsible for emissions levels that are in line with U.S. climate goals. It could do so by setting a limit on the overall coal tonnage, coal British thermal unit potential, or pounds of carbon dioxide associated with burning. Of these options, the most straightforward way for the BLM to administer the offering would be to set the cap on coal tonnage.

More than 90 percent of coal produced in the United States is thermal coal bound for coal-fired power plants. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, or EIA, coal emissions from this lion’s share of production generally range from 2,791.60 pounds of carbon dioxide per short ton of lignite coal to 4.931.30 pounds of carbon dioxide per short ton of bituminous coal.

Since different coal types emit different levels of carbon dioxide per ton, the tonnage cap could be broken down by coal type so that the overall associated emissions remain in line with climate change reduction goals. Alternatively, the BLM could simply auction the rights to produce coal associated with a set amount of greenhouse gas emissions and let the market decide what types of coal will be produced. Either way, the BLM should factor in the varying emissions levels by coal type when reconciling the overall needs of the coal market with an emissions cap aligned with U.S. climate goals.

To adhere to climate goals over time, the BLM would be responsible for lowering the tonnage caps for each coal type to meet national greenhouse gas emission reduction targets.

U.S. climate goals

On March 31, 2015, President Obama submitted greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. The United States’ goal is to reduce climate pollution by 26 percent to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, make its best effort to reduce by 28 percent. According to the White House, “This ambitious target is grounded in intensive analysis of cost-effective carbon pollution reductions achievable under existing law and will keep the United States on the pathway to achieve deep economy-wide reductions of 80 percent or more by 2050.”

On January 16, 2016, Secretary Jewell announced that the U.S. Geological Survey would establish a public database of annual carbon emissions from fossil fuels developed on public lands. These baseline data will provide key information to both the public and federal land managers for reducing carbon pollution from the federal coal estate.

In order to reassess the caps on a rolling basis, the BLM should set coal leasing levels on five-year cycles, similar to the DOI’s five-year program for offshore oil and gas leasing. A five-year cycle enables the agency to update its leasing targets based on new technologies, changes to national energy and climate policies, and other developments. If zero-carbon coal combustion technology is rendered economically and technically viable, for example, the BLM could decide to increase certain subcaps or to exempt coal used by zero-carbon sources from caps.

By shortening the lease terms from an initial term of 20 years for all new and modified coal leases, the BLM would be able to keep up with the emissions burden associated with federally owned coal and adjust the total allowable emissions for the next five-year period to account for any overshooting or undershooting of the previous five-year period’s target.

Additionally, a five-year lease cycle similar to the offshore oil and gas leases administered by the DOI’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management could open up multiple opportunities for the public to provide comments. Increasing public input would help alleviate the lack of transparency for which the Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General have criticized the current federal coal program.

Proposed 5-year coal leasing process

- The BLM issues an initial Request for Information and Comment on topics that include the level of total allowable emissions and feedback on setting bidder integrity standards. (45-day comment period)

- The BLM issues a Draft Proposed Program that outlines the tonnage caps—based on total emissions—and criteria for eligible participants—based on bidder integrity standards—for the upcoming auction for five-year leases. (60-day comment period)

- The BLM issues a Final Proposed Program that establishes tonnage caps and auction rules. (30-day comment period)

- The BLM holds an auction for eligible bidders to bid on coal credits.

- Once the auction is complete, bidders may submit proposals to the BLM for specific tracts of land where they wish to use their credits to mine.

Bidder integrity standards

As part of its five-year planning process, the BLM should establish clear bidder integrity standards that companies will have to meet to be eligible to bid in the credit auction. These integrity standards would factor in the long-term effects of mining on nearby communities and taxpayers. The labor, economic, and environmental landscapes altered by coal companies are currently considered in the leasing process—to the extent that they are considered at all—but only as they relate to a specific tract. Bidder integrity standards would enable the BLM to consider these critical concerns at the company level where variations in financial solvency, mine-site reclamation, and worker treatment occur.

When determining bidder eligibility, the BLM should take a risk-adjusted approach that considers bidders’:

- Past records of violating environmental or worker safety regulations—including those obtained before filing for bankruptcy

- Ability to meet reclamation obligations

- Ability to put up collateral sufficient to cover future reclamation without self-bonding

- Adherence to ethical business standards of balancing worker benefits and executive pay, especially in the face of bankruptcy

Conclusion

As the Bureau of Land Management undertakes a programmatic review of the federal coal program, it must implement reforms that enable the program to better meet the United States’ near- and long-term energy and climate needs. At the same time, these reforms must address the economic and environmental concerns of coal-dependent communities as the United States transitions to cleaner energy sources.

CAP’s proposed five-year cycle credit auction would allow the BLM to better correct for the inherent noncompetitive nature of the federal coal leasing program and benefit from additional public input. This framework would allow for continued federal coal leasing in the context of U.S. climate goals and therefore has the opportunity to garner sufficient public and political support to be stable, enduring, and effective for many years to come.

Mary Ellen Kustin is the Director of Policy for the Public Lands team at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Alison Cassady, Michael Madowitz, Jenny Rowland, Nicole Gentile, Victoria Ford, Pete Morelewicz, Carl Chancellor, and Meghan Miller for their contributions to this issue brief.