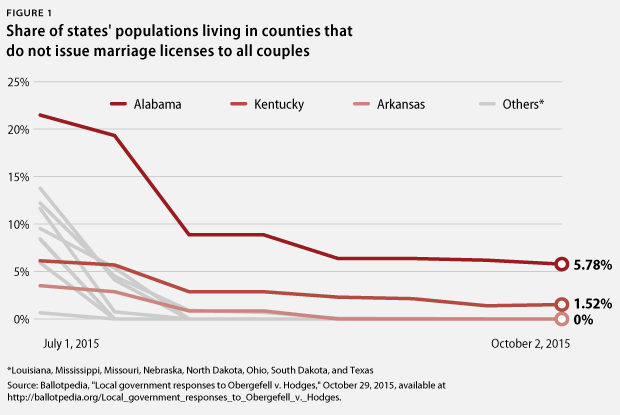

It has been five months since the U.S. Supreme Court declared that the U.S. Constitution protects the right to marry for same-sex couples, and 99.9 percent of Americans now live in counties that offer marriage licenses to all couples, according to data on county compliance from the website Ballotpedia. But in Alabama and a handful of other states, judges and magistrates are defying the Court and the Constitution by refusing to implement the marriage equality decision.

The counties where judges or magistrates still refuse to recognize marriage equality are in states that have seen increasingly politicized judicial elections and a flood of campaign cash into those races. Politicized elections require judges to cater to public opinion, instead of protecting individual rights in the face of political pressure.

The most substantial resistance to marriage equality now occurrs in Alabama, where local judges and even the state supreme court have defied federal court orders to issue licenses to all couples. Months before the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, a federal judge in Alabama struck down the state constitution’s ban on same-sex marriage. But the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that state judges did not have to comply with the federal court order, even though the U.S. Constitution gives federal law supremacy over state law.

Judicial resistance to marriage equality has taken two forms. Some judges and magistrates deny the U.S. Supreme Court’s authority to issue the ruling. Other officials justify their refusal to grant marriage licenses with an overly broad interpretation of religious freedom that trumps the Constitution, when it comes to marriage equality.

Ballotpedia tracked the jurisdictions—including counties in Alabama, Texas, and Kentucky—that still refuse to offer marriage licenses to all couples. Alabama is, by far, the state with the highest proportion of its population living in counties that have not recognized marriage equality. As of October 2, 2015, nearly 6 percent of Alabamans live in counties that do not offer marriage licenses to all couples. More than 1 in 20 Alabama citizens still cannot receive a marriage license at their local courthouse, despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling more than five months ago.

All of these resistant judges serve in conservative states where marriage equality is unpopular. A June 2015 poll from the Pew Research Center found that the South is the only region of the United States where a near-majority of people still oppose marriage equality. A post-Obergefell poll by the Public Religion Research Institute found that opposition to marriage equality was strongest in Arkansas, Alabama, and Mississippi—where opposition was around 60 percent. Two Southern state supreme courts—in Mississippi and Louisiana—have not defied marriage equality, although some dissenting justices argued that they should have.

Who decides who can marry?

The Obergefell ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court in June brought marriage equality to the entire country, but federal judges do not conduct marriages. Each state decides individually how couples can obtain marriage licenses. In many states, including Alabama, marriage licenses come from probate judges. In Kentucky and other states, licenses are handed out by elected clerks of local courts. North Carolina and several other states offer marriage licenses through judicial officials called magistrates.

There are, however, Southern states where marriage equality is nearly as unpopular, but judges in those states are not resisting Obergefell. For example, more than half of South Carolina voters oppose marriage equality, but judges there—who are chosen by the state legislature—offer marriage licenses to all. Georgia’s judges are chosen in nonpartisan elections that have not been flooded with campaign cash, and Ballotpedia reports that every county in the state offers marriage licenses to all couples.

The states where judges still resist equality are also states that have experienced, or are beginning to see, highly politicized, multimillion-dollar supreme court elections. In the 1990s, for example, supreme court elections in Alabama and Texas were awash in a wave of corporate campaign cash that flipped the states’ high courts from all-Democrat to all-Republican. Such politicized elections create pressure on judges to rule in ways that please voters, instead of protecting individual rights even when doing so is unpopular.

Social issues such as marriage equality have loomed over judicial elections in Alabama and Texas. Both states’ supreme courts include a justice who refused to remove Ten Commandments displays from their courtrooms. Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore was reelected in 2012—after he was booted from the court a decade earlier for defying a federal court order to remove a 2-ton monument of the Ten Commandments. His 2012 campaign platform included calling marriage equality “the ultimate destruction of our country.” Texas Justice John Devine was elected in the same year, and his campaign website still states that he “received national acclaim by refusing to remove a painting of the Ten Commandments from his courtroom.”

Some judges are also resisting marriage equality in Southern states where campaign donations in judicial elections are increasing. In Kentucky, for example, the 2006 supreme court election broke spending records and two candidates campaigned on their anti-abortion views. More recently in Kentucky, Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis went to jail for refusing to honor Obergefell. During the politicized 2006 election, a Washington University in St. Louis professor polled Kentuckians about their supreme court, and nearly half of respondents said that judges should “be involved in politics, since ultimately they should represent the majority.” In 2014, Tennessee saw its first multimillion-dollar supreme court race, and at least one elected judge has since lashed out over Obergefell.

Arkansas has also seen big increases in campaign cash in its supreme court races during the past decade, and in the midst of last year’s expensive contest, the justices avoided issuing a ruling on a marriage equality lawsuit. Arkansas Justice Donald Corbin, who retired in December 2014, recently conceded that the court actually voted 6-1 in favor of marriage equality but did not release its ruling for more than a year, until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled. The Arkansas trial court judge who initially overturned the state’s ban on same-sex marriage faced threats of impeachment, and Justice Corbin noted that he himself previously received threats to his safety after joining rulings to strike down both the state’s criminal sodomy statute and a law banning same-sex couples from adopting children.

There was some initial defiance of Obergefell in states where some lower-court judges are chosen in contested elections while justices are appointed through a merit-based selection system. The data from Ballotpedia shows that in Missouri, South Dakota, and Tennessee, a substantial portion of counties refused to issue marriage licenses to all couples on July 1—just days after Obergefell. But those defiant jurisdictions quickly gave in, and the percentage of counties that did not offer licenses to all couples was nearly zero within a few days of the Obergefell ruling.

Defying federal courts’ authority over marriage equality

In order to justify its defiance of marriage equality, the Alabama Supreme Court has twisted the law and lashed out at the federal courts. Alabama Justice Tom Parker faces an ethics complaint for saying that the U.S. Supreme Court in Obergefell had “jumped outside of all the precedents in order to impose their will on this country.” When the Alabama Supreme Court instructed lower court judges to ignore the federal court order on marriage equality, it called the order “a direct assault on this Court’s sovereignty.” The court argued that there was “no legal justification for [U.S. District Court Judge Callie] Granade’s unprecedented attack upon the integrity of this court.” Judge Granade stayed her order until the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling, a move that Ian Millhiser of ThinkProgress criticized because it “rewards the state supreme court’s intransigence.”

The Alabama court’s opinion explicitly stated that even a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in favor of marriage equality would “not necessarily end the conflict.” The Alabama court warned, “Given the self-evident reasoning against such a holding, … such a decision by the [U.S] Supreme Court would naturally and immediately raise a question of legitimacy.” Other elected justices now echo arguments from the Alabama Supreme Court and the Obergefell dissenters that the ruling was illegitimate.

The Mississippi Supreme Court recently granted a divorce to a same-sex couple, acknowledging marriage equality in the process, but two justices argued that the court did not have to follow Obergefell. The dissenters in Mississippi quoted anti-marriage equality legal scholars and embraced the proposition that “it is possible for the United States Supreme Court to render an opinion so devoid of constitutional analysis or reason that it exceeds … the Court’s authority under Article III of the United States Constitution.” Astonishingly, one of the dissents implied that Cooper v. Aaron, a unanimous 1958 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that compelled Arkansas and other states to implement Brown v. Board of Education, was wrongly decided. In a sobering admission that underscores the pressure placed on jurists, Justice Randy Pierce—who voted with the majority in its divorce ruling—said, “As an elected member of this court, the politically expedient (and politically popular) thing for me to do” is vote against marriage equality.

In Louisiana, Justice Jefferson Hughes dissented from his court’s opinion acknowledging marriage equality after Obergefell. He cited no legal authority in his dissent but claimed that “the most troubling aspect of same-sex marriage is the adoption by same-sex partners of a young child of the same sex,” presumably referring to the unsubstantiated and offensive notion that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children. His colleague, Justice Jeannette Knoll, felt compelled to follow Obergefell but made it very clear that she disagreed with the ruling and warned of its “horrific impact.” Justice Knoll described Obergefell as “a legal fiction” and “a mockery of those rights explicitly enumerated in our Bill of Rights.”

Religion does not trump judges’ duty to the Constitution

Religious freedom has become the rallying cry for forces opposed to marriage equality who seek to limit the reach of the Obergefell ruling. Several states are considering their own, overly broad versions of the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, or RFRA, that would justify discrimination against same-sex couples. Some judges and other elected officials have also turned to religion to justify defying Obergefell.

In North Carolina, lawmakers passed a bill allowing judges to decline to issue marriage licenses for any marriages to which they have a religious objection. The Texas Attorney General also issued an order allowing judges to opt out for religious objections.

The Alabama Supreme Court is currently hearing an appeal from a probate judge who wants a similar religious exemption from issuing marriage licenses. In deeply conservative Alabama, one has to wonder: Just how many elected judges would sign up for such an exemption?

Alabama Chief Justice Moore has a broad view of religious freedom—at least when it comes to Christians. In January 2015, he argued that the Constitution’s right to free exercise of religion only applies to those who worship the God of the Christian Bible. “Everybody, to include the United States Supreme Court, has been deceived as to one little word in the first amendment called ‘religion,’” Chief Justice Moore stated. After video of the remarks surfaced, the chief justice backed down from his assertion.

Some local officials across the country have unsuccessfully petitioned for a religious freedom exemption to their duties. A Kentucky federal judge, in rejecting Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis’ request for a religious exemption to the duties of her office, said: “The State is not asking her to condone same-sex unions on moral or religious grounds, nor is it restricting her from engaging in a variety of religious activities. … However, her religious convictions cannot excuse her from performing the duties that she took an oath to perform.”

The same federal judge also noted that 57 of Kentucky’s 120 elected county clerks asked the governor to call a special session to address the issue of religious freedom after Obergefell. The judge concluded, “Our form of government will not survive unless we, as a society, agree to respect the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions, regardless of our personal opinions.”

Judicial elections make it harder to defend individual rights

As Justice Randy Pierce in Mississippi noted, it is “politically popular” for judges in conservative states to defy marriage equality. A recent op-ed written by advocates against marriage equality in Alabama stated, “Alabamians elected justices to the Alabama Supreme Court with confidence that they would judge rightly in the fear of God.” This political pressure is not a problem for judges who are appointed, not elected. Appointed state supreme courts, such as those in Hawaii and Massachusetts, led the way to marriage equality before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled.

The 2010 Iowa judicial elections made it very clear what can happen when judges who rule for marriage equality are on the ballot in conservative-leaning states. That year, three Iowa Supreme Court justices were ousted from the bench—just one year after they unanimously struck down the state’s ban on same-sex marriage. Anti-marriage equality groups from outside the state spent more than $1 million attacking the justices.

Judges must at times make unpopular decisions because the law and the facts compel them to do so. Even if marriage equality is unpopular in Mississippi and Alabama, the judges there must follow the U.S. Constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court is the ultimate authority in defining the Constitution and, unlike most state courts, its members will never have to be reelected or even re-confirmed to keep their jobs. In Louisiana, Justice Jeannette Knoll seemed to acknowledge this when she referred to the Obergefell majority as “five unelected judges” and “five lawyers beholden to none and appointed for life.”

When deciding how to choose judges, drafters of constitutions must balance independence with accountability to the public. The founders of the United States established a judicial system that ensures complete independence for federal judges, whose salaries cannot even be reduced while they are in office. Of course, the public still has real influence over who sits on federal courts, as their elected representatives nominate and confirm federal judges.

Most state constitutions strike the balance in favor of accountability by making judges dependent on voters to keep their jobs. However, judicial elections are becoming increasingly expensive and politicized, with more attack ads fueled by more money from special interests with a stake in lawsuits before these courts. More politicized elections mean more pressure for judges to please a majority of voters.

Theoretically, legislators and governors are supposed to reflect the will of a majority of voters. Judges, on the other hand, should be different. The judicial branch is the one branch of government where individuals are supposed to stand on equal footing with powerful institutions. But elections make it exceedingly difficult—if not impossible—for judges to stand up for individual rights in the face of political pressure.

Studies have found that money in judicial elections correlates with rulings against criminal defendants. A recent Reuters investigation found that judges who were chosen in contested elections are more likely to sentence defendants to death than other jurists. A 2011 study of Alabama judges found that judges were more likely to sentence defendants to death during election years. Citizens cannot trust that judges who must face reelection will protect the rights of unpopular groups.

If citizens want courts that protect individual rights and check the power of the political branches of government, they should push for a system of appointing judges in their states. Judges who do not have to face reelection can focus on the facts and law in each case, without worrying about whether the ruling will be popular. It is crucial that states that continue electing their judges also make concerted efforts to minimize the role of partisanship, big money, and politics in the courts.

Billy Corriher is the Director of Research for Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress.