Ten years ago, the financial crisis began, kicking off the Great Recession. U.S. households lost $19 trillion in wealth, and 8.8 million Americans lost their jobs. The crisis was fueled by predatory lending practices and lax oversight, with its ramifications felt not just in every state, but around the globe. As a result, then-President Barack Obama and Congress strived to limit the harm of a future crisis—and through passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, coupled with other laws and administrative actions, they built a stronger, safer financial system without unduly hampering lending or economic growth.

While the economic recovery has been uneven, both the financial sector and the overall economy today are back to where they were before the crisis began in 2007—if not at even greater levels. In October 2009, the nation’s unemployment rate hit 10 percent and currently stands at 4.1 percent—lower than the 4.4 percent rate reached before the crisis. Yet, the Trump administration and Congress seem to have forgotten the causes and consequences of this crisis as they seek to undermine the key protections put in place to prevent it from happening again.

Last June, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the so-called Financial Choice Act, which would massively weaken financial safeguards and enforcement by taking a wrecking ball to these protections, and the House Financial Services Committee continues to review and pass other dangerous bills. Meanwhile, in December, the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs passed S. 2155, or the Economic Growth, Regulatory Reform, and Consumer Protection Act—a major deregulatory bill that would deregulate 25 of the 38 largest banks and open wide the doors to massive loopholes in mortgage lending, similarly risking another crisis. And at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, created by the Dodd-Frank law, controversial acting Director Mick Mulvaney is drastically scaling back the agency’s rule-making and enforcement.

These decisions ignore those who pay for rolling back regulations: American consumers, homebuyers, and investors. They are a solution in search of a problem; the overwhelming majority of voters want tougher rules and enforcement on Wall Street, not looser ones.

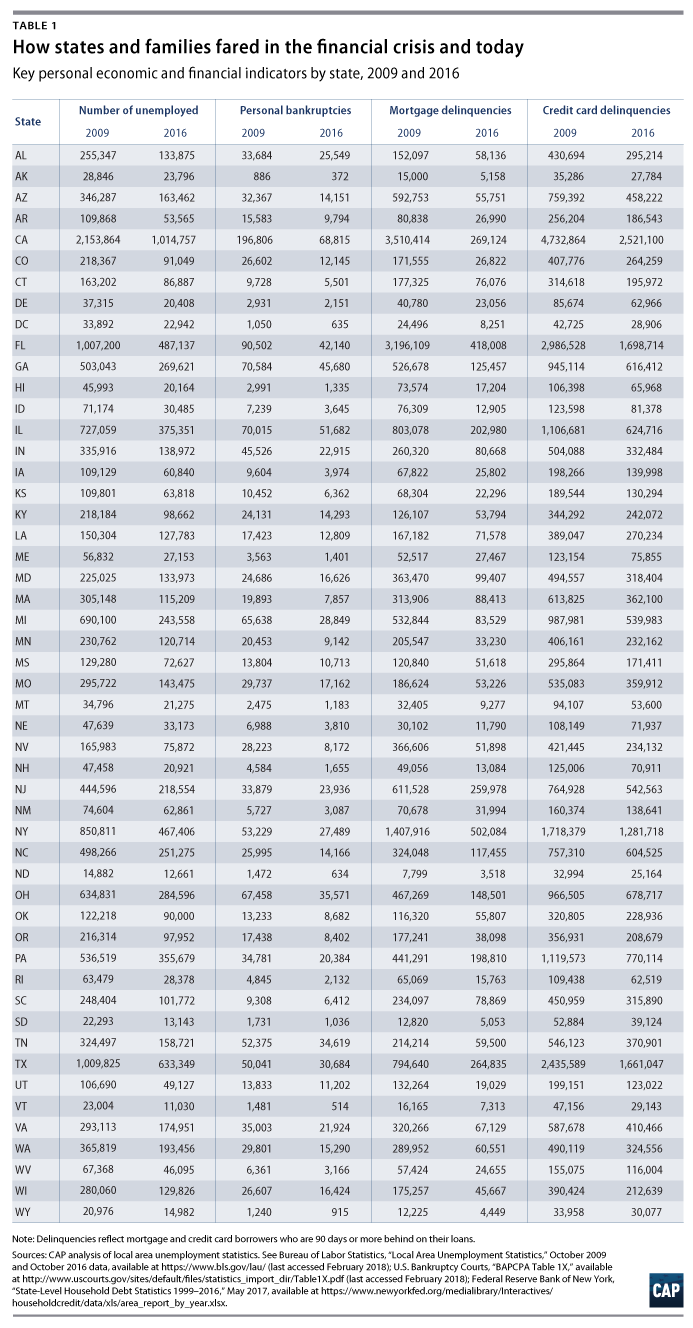

In case members of Congress have forgotten what families dealt with during the financial crisis, Table 1 shows unemployment levels and bankruptcies, as well as the number of borrowers 90 days or more behind on their mortgages and credit cards in every state for 2009 and 2016, the most recent year all of these data are available.

Joe Valenti is the director of Consumer Finance at the Center for American Progress.