By Adam Hersh and Isha Vij | January 7, 2011

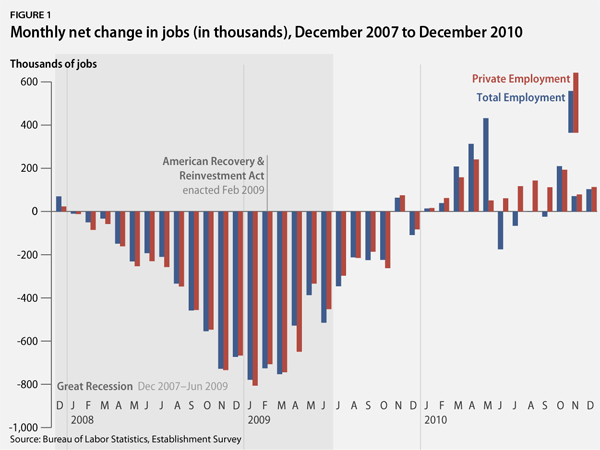

The economy added 103,000 jobs in December, which continues a positive trend of employment growth. But a closer look at the numbers reveals that hopes of an accelerating job market recovery are once again disappointed. The slow and volatile pace of employment growth in recent months should be a warning sign to policymakers that a still-fragile recovery needs consistent policies targeted at jobs, jobs, and more jobs. As a new, more conservative Congress assumes the reins of government, Americans need to know that cutting the government’s budget and failing to make investments for recovery and long-run growth will only make our economic problems worse.

Overall employment gains were insufficient to even keep pace with job demands from population growth. And these gains were concentrated in low-wage, low-productivity industries, further aggravating job seekers. Unemployment has stood at or above 9 percent for a record 20 months now, which is the longest spell since the Department of Labor began reporting this statistic in 1948. The labor market is not out of the woods yet, either. Private forecasts predict unemployment to stay above 9 percent at least through 2011.

December’s unemployment rate dropped from 9.8 percent to 9.4 percent, but the change highlights the frustrations of job seekers more than substantial employment gains. The number of people counted as unemployed fell by 556,000. Presumably, many have given up looking for work in an environment where there are nearly five people for every job opening. An estimated 260,000 people left the labor force altogether and the number of people re-entering the labor force with new hopes of finding work fell by 19,000 in December.

The number of people unemployed and looking for work for more than six months grew by 113,000 last month. In total, more than 6.4 million people are long-term unemployed—44.3 percent of all unemployed people searching for work, and 300,000 more people than a year earlier. The typical unemployed worker in December had been out of a job and searching for work for 22.4 weeks—a full two weeks longer duration than one year ago.

Meanwhile, private-sector employment growth of 113,000 was led by service-producing industries. Aside from the health care industry, which added nearly 36,000 jobs, employment gains were concentrated in relatively low-wage and low-productivity parts of the economy. The hospitality industry added 47,000 net new jobs, including 25,000 in food service and 16,000 in amusements and gambling businesses. Retail trade added a mere 12,000 net new jobs. When this number is viewed alongside the sluggish household income and consumer spending data released last month it suggests that consumers did not deliver a late boost to holiday shopping.

Manufacturing employment added a modest 10,000 jobs after floundering in the second half of 2010. Elsewhere, the construction sector cut 16,000 jobs as the economy continues adjusting from the overinflated real estate bubble. Private-sector employment gains also were partly offset by steep job cuts from local governments facing recession-related budgetary pressures. Local governments cut a total of 20,000 jobs, including more than 7,000 teachers and other education professionals.

December’s employment release from the Department of Labor adds to the evidence that labor market conditions are dominated by too much slack in the U.S. economy. Average hours for private-sector production and nonsupervisory workers were essentially unchanged in December at 33.6 hours per week, up less than half an hour from one year earlier. Today, nearly 9 million workers are employed part time due to not being able to find work with sufficient hours—almost double the number from before the start of the recession in December 2007. Acceleration of temporary help jobs seen earlier in 2010—often a harbinger of future permanent hiring—showed signs of wavering in December as hiring for temporary help services fell back to 16,000 jobs from 31,000 in November. This is about a third of the pace of temporary hiring from a year earlier.

December’s statistical release also indicates that employment growth in October and November was better than initially thought. Job growth was revised upwards to 210,000 and 71,000, respectively. But even with this faster pace of job creation, the economy will not recover to pre-recession employment rates in any economically relevant time frame at the current three-month job growth trend.

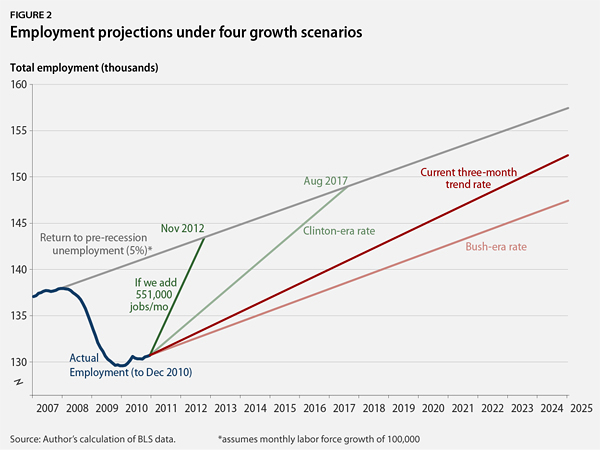

Figure 2 shows the recent trend in job growth and projects how long it will take the economy to recover to the pre-recession employment rate under several historical growth scenarios. The economy, for example, added an average of 200,000 jobs per month in the economic expansion of the booming 1990s. Growing at the pace of the Clinton years, the economy could return to 5 percent unemployment by August 2017.

During the 2000s economic expansion under President George W. Bush, the economy added an average of 97,000 jobs per month. At the job growth pace of the Bush years, the economy would never recover to pre-recession unemployment levels and the unemployment rate would continue increasing.

Employment growth has averaged 128,000 jobs per month over the past three months. That’s faster than the pace under the Bush-era economic recovery—and recovering from a much deeper recession—and eventually converges on 5 percent unemployment. But the current pace of job growth is insufficient for labor market recovery in any relevant time frame. Further, recovery to 5 percent unemployment by November 2012 would require adding more than 551,000 jobs per month over the next two years.

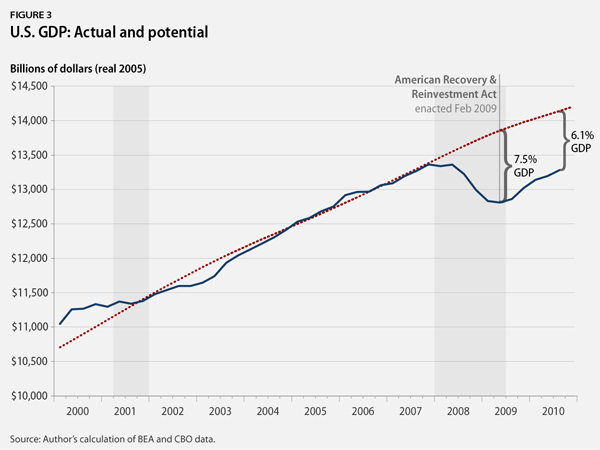

The continuing slow pace of employment recovery and labor market slack stem from one factor: insufficient aggregate demand in the overall economy. Figure 3 shows the hole left in the economy since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007. You can see how far actual U.S. economic activity, or gross domestic product, has fallen below its full potential if workers and the economy’s productive assets were to be used at full employment.

At the height of the recession this output gap grew as large as 7.5 percent of GDP. The U.S. economy has clawed back to a 6.1 percent output gap with the help of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, monetary policy implemented by the Federal Reserve, and a range of other fiscal policy tax cuts, income supports, and investments in public infrastructure.

Figures 2 and 3 show that we still have a long way to go in terms of economic growth and job recovery. The fragile economic situation seen in December’s employment data release indicates yet again that the economy needs consistent, continued support for job creation to secure recovery.

To read the full column, click here.

Adam Hersh is an Economist and Isha Vij is the Special Assistant for Economic Policy at American Progress.

###