In 1975, only a generation ago, more than half of American families with children (52.6 percent) comprised a male breadwinner and a female homemaker. In 2011 just one in five families fit that configuration (20.7 percent), while single parents headed one in three households (31.9 percent), and the remaining families consisted of two working parents. When all the adults in a family are employed, it not only means that there is no one at home to sign for packages or wait for the refrigerator repairperson to arrive—it also more importantly means that there is often no one home to provide care when children get sick. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, dual-income families in the 2000s were 10 times more likely than single-income families in the 1970s to have a wage-earner miss work in order to care for a sick child.

Most workers whose employers offer paid sick days are able to take them in order to stay home and provide care for ill family members. Others with access to workplace flexibility can work from home or otherwise change their schedules in order to stay home with a sick child. But all too often this is not an option for working parents because they do not have access to paid sick leave or workplace flexibility. This can place parents in a precarious situation when their children fall ill—something which can happen quite frequently.

A recent study conducted by the University of Michigan found that almost two-thirds (62 percent) of parents whose children were in child care said that over the past year, their children could not attend at least once due to illness. Nearly one-quarter (23 percent) said their child was sent home from child care at least once in the previous year after falling ill. Even worse, one-third of parents with children under age 6 said that they feared losing pay—if not losing their job—when they had to take time off from work in order to care for their sick children.

Unlike every other advanced economy, the United States does not guarantee workers the right to paid sick days or paid parental leave after the arrival of a new child. Other economies such as Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland are excelling while guaranteeing leave benefits for workers. There is no good reason why the United States should not follow suit, and steps should be taken to implement the following:

- Workplace policies that would promote flexibility such as those promoted by the White House

- A national paid family and medical leave insurance program such as the program proposed by the Center for American Progress

- Paid leave legislation such as the Healthy Families Act, which would allow workers to earn up to seven paid sick days per year

These policies would go a long way to help bring our nation up to speed and would allow working mothers and fathers to be both good workers and good parents. This brief focuses on how vital these benefits can be to our nation’s workers, beginning with paid leave.

Paid leave

Fast facts: Parents in the workforce

- Three-quarters (74.8 percent) of parents between the ages of 25 and 44 are currently employed, and they make up slightly more than half (53.6 percent) of all workers in that age group.

- 9 in 10 dads (90.8 percent) and about two-thirds of moms (63.3 percent) work for pay outside of the home.

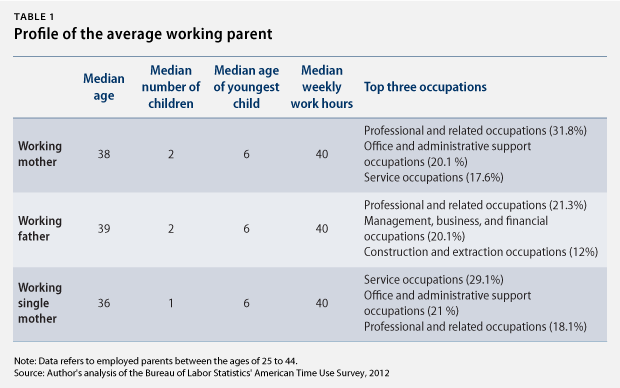

- About one-quarter (22.12 percent) of working mothers are single moms—in fact, single mothers are just as likely to be employed as married mothers, although they are about twice as likely to be unemployed and looking for work. (see Table 1)

While there are currently no federal requirements to do so, some employers voluntarily provide paid leave to their workers so that they do not lose wages when they cannot be at work. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, as part of the annual American Time Use Survey, collected data in 2011 on workers’ access to various forms of paid leave and workplace flexibility. These data, analyzed here, show that millions of workers lack access to paid leave and flexibility, with the most vulnerable workers being those least likely to have these benefits.

Regardless of gender or marital status, the average working parent is strikingly similar in characteristics such as age, number of children, and weekly work hours. While single working mothers are slightly younger and tend to have fewer children, the majority of them work full time with similar work hours to married women. Single mothers differ from married parents in that they are much more likely to work in service occupations, which tend to offer less pay and fewer occupational benefits such as paid leave.

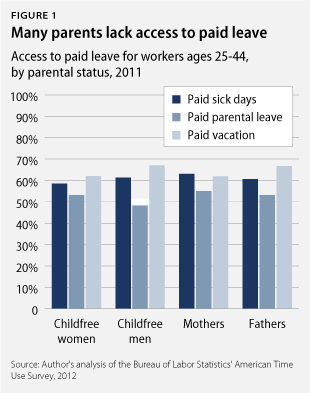

Even though parents are more likely to need to take paid sick leave than child-free workers—because in addition to their own illnesses, they may need time off to provide care for a sick child—they are only slightly more likely to have access to it. While working mothers are slightly more likely to have paid sick leave than women without kids (63.1 percent compared to 58.5 percent), fathers are not (60.6 percent compared to 61.3 percent of childless men). (see Figure 1) This leaves 4 in 10 parents without a single paid sick day to take if their child is too sick to go to school or attend child care.

In addition to low levels of access to paid sick days, only about one-half of workers have employer-provided paid parental leave that can be taken after the birth or adoption of a child. Workers in the United States, unlike those in every other industrialized economy, are not currently guaranteed the right to paid leave after the birth or adoption of a child. Yet most men and women eventually become parents—by age 40, three-quarters of men (76 percent) and 85 percent of women have had at least one child.

Some workers have access to unpaid caregiving leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, but due to eligibility requirements only about half of the workforce qualifies. Since the only available leave is unpaid, many workers cannot afford to take it even if they qualify. Of workers who qualified for unpaid leave but did not take it, nearly 80 percent cited financial reasons.

Critics often claim that it is unnecessary to offer paid leave that is specifically earmarked for sick days or parental leave since workers may have access to other forms of paid leave. Paid vacation is the most commonly offered paid leave benefit, but only about two-thirds of all workers have access to it. Even if more workers had access to paid vacation, this type of leave often cannot be taken on short notice the way that paid sick days can. The average worker with paid vacation receives 10 days off per year, which is far less than is recommended by physicians to recover from childbirth or to get accustomed to caring for a new baby. Generally physicians recommend at least six weeks of recovery after childbirth, though many advocate for more time off.

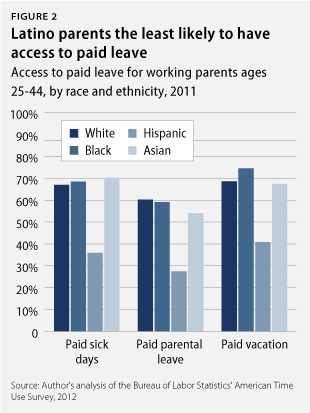

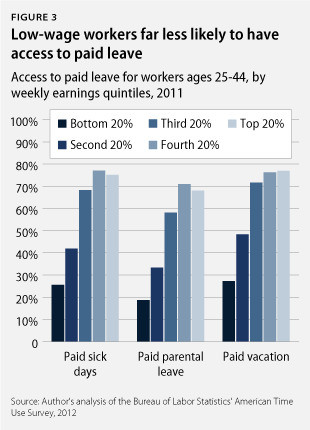

Finally, access to paid leave is not evenly distributed across the workforce. Working parents with higher incomes and those who are non-Hispanic are significantly more likely to have access to any form of paid leave compared to low-income or Latino workers. (see Figures 2 and 3)

Flexibility

Much has been made of the importance of workplace flexibility for parents as a way to improve work-life balance. Flexibility is certainly useful when it allows working fathers and mothers to spend more time with their families without necessarily having to cut back their work hours or reduce their salaries. Yet the majority of parents do not have the ability to change the hours, days, or location of their work. (see Figure 4)

Less than half of parents can change the hours or days that they work, and only about one-quarter are able to change their location. Without this flexibility, if a parent needs to pick up a child from daycare, attend a parent-teacher conference, or see their child perform in a recital, they may not be able to rearrange their schedule without losing pay—or potentially their job.

Workers with access to paid leave also are more likely to have access to workplace flexibility, so those without adequate leave policies often have few other options. Similar to paid leave, workers with higher wages and those who are white are more likely to have flexibility than low-wage workers or people of color. (see Figure 5)

Conclusion

Let’s be clear: All workers deserve access to sensible and fair paid leave and workplace flexibility policies, whether they have children or not. Parents are not the only workers who need access to leave—it should be available to all workers, whether it is to provide care for another family member, to recover from an illness, or to deal with any other life event that would temporarily prevent someone from being at work. But we should also recognize that while parents are not necessarily more deserving of paid leave or flexibility than workers without children, this is a unique moment in modern American history—for the first time most parents are in outside employment, and most homes no longer have a full-time, stay-at-home caregiver.

The answer is not to send mothers (or fathers) back to the home front but instead to recognize that our society has changed and that our workplace policies must change along with it. Other nations recognized this need and managed to implement policies that benefit working families without harming their economies. New research continues to demonstrate that paid leave can actually save businesses money in the long run.

Most parents are workers, and most workers are parents. Rather than engaging in handwringing over how parents should individually manage these two spheres of their lives, we should proactively implement policies that would help all workers better balance their obligations in the marketplace and in the home.

Sarah Jane Glynn is a Policy Analyst with the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress.