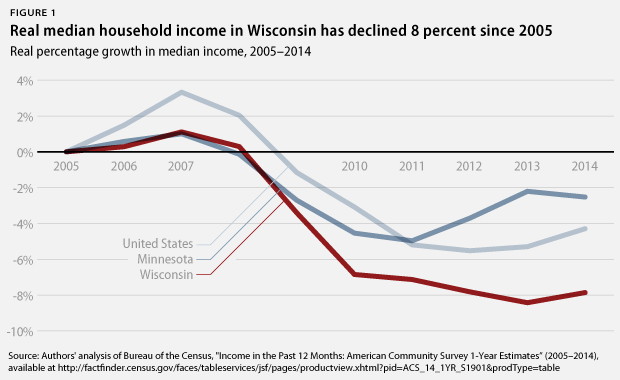

Since 2005, real median household income has fallen 7.9 percent in Wisconsin—a far sharper decline than what has been seen across the border in Minnesota or nationwide. The biggest reason why middle-class incomes have not grown in recent years is that wages in the state have remained stagnant; the Wisconsin median wage has grown by a scant 12 cents since 2005.

Economists point to several reasons for stagnant wages nationally, including globalization and increased automation. But there is a growing consensus that the decline of labor unions has been a key contributor to slow middle class wage growth and inequality over the last 40 years. Studies estimate that as much as 30 percent of the increase in wage inequality among male workers over roughly the same period is the result of declining unionization.

The state of unions and the economy in Wisconsin

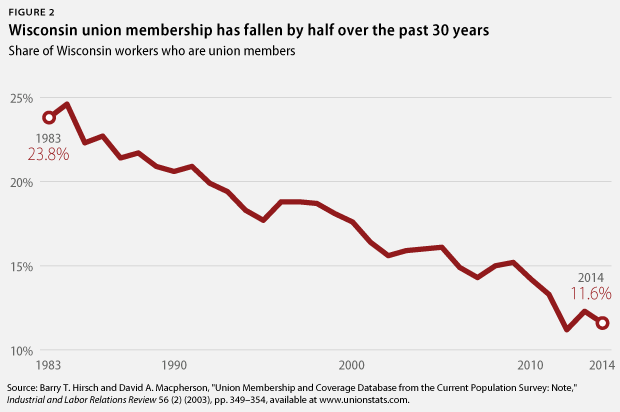

Wisconsin was once one of the nation’s most unionized states—but no longer.

- In 1983, 23.8 percent of Wisconsin workers were members of a labor union, making Wisconsin the 12th most unionized state in the country.

- In 2014, union membership stood at just 11.6 percent of Wisconsin’s working population.

- The 2015 passage of a so-called right-to-work law will further weaken the Wisconsin labor movement. The law gives some workers a free ride by allowing them to enjoy the benefits of a union contract, such as higher pay, without paying the cost of negotiating that contract.

Unions in Wisconsin have fallen victim to the same forces that have caused union membership to decline across the country: the decline of heavily unionized sectors such as manufacturing and lax enforcement of federal labor law. Wisconsin has also suffered from a forceful antiunion agenda led by Gov. Scott Walker (R), who signed a law to curtail public sector bargaining in 2011 and the so-called right-to-work law in 2015.

Notably, Gov. Walker’s recent antiunion push and years of steep tax cuts have failed to improve Wisconsin’s fiscal situation. Gov. Walker was forced to delay $100 million in debt payments earlier this year in order to fill a budget gap in fiscal year 2014, and signed into law a budget for FY 2015-2016 that slashed funding for the University of Wisconsin system by $250 million in order to make ends meet.

Meanwhile, the economic growth promised by Gov. Walker has yet to materialize.

- From January 2011 to August 2015, Wisconsin added approximately 159,000 private-sector jobs, a growth rate of 6.9 percent.

- Neighboring Minnesota’s private-sector employment grew 8.7 percent; the U.S. growth rate was 10.8 percent over the same period.

- Had Wisconsin’s private sector grown at the same rate as that of Minnesota, the state would have added more than 43,000 additional jobs since January 2011.

- Real Wisconsin median household income in 2014 was 1 percent below its 2010 level; real median household income in Minnesota increased by 2 percent over the same period.

How unions help Wisconsin workers

One way that policymakers can help the economy work for all Wisconsinites—not just the wealthy few—is by supporting policies that help workers form unions, which provide them with a number of benefits.

Unions raise wages

Unions boost wages because they give workers a unified voice with which to bargain collectively with their employer. The Center for American Progress used data from the U.S. Census Bureau to determine how much unions raise wages for Wisconsin workers, controlling for several characteristics of workers including their education, industry, and occupation. CAP found that, on average, Wisconsin workers earn more money if they are covered by a union contract.

- Unionized Wisconsin workers make 11.7 percent more.

- Unionized female Wisconsin workers make 9 percent more.

- Unionized nonwhite Wisconsin workers make 9.8 percent more.

- Unionized Wisconsin workers without a college degree make 13.4 percent more.

These findings suggest that unions continue to be a viable method for boosting wages for Wisconsin workers, especially since evidence shows that unions, if anything, raise the wages of nonunion workers because nonunion employers have to compete with union employers’ higher wages.

Unions close the gender gap

The share of female workers has grown over the last four decades, and ensuring that female workers make as much as their male counterparts is therefore an effective way to raise wages. Unions help reduce this pay gap.

- The median Wisconsin woman who works full-time earns 17.5 percent less per hour than her male counterparts.

- Wisconsin women who work full time still make 15.3 percent less than Wisconsin men, even after controlling for differences in education, industry, occupation, and several other variables.

- The pay gap is 26 percent smaller between Wisconsin men and women who are in a union than for those who are not.

Unions fight for policies that help all workers

Unions are strong advocates for policies that help all workers. According to research by Princeton University political scientist Martin Gilens, unions are among the few interest groups that actually promote the interests of the middle class—through their work to raise wages, increase access to health care, and improve retirement security. Unions also increase political participation and voter turnout, resulting in a stronger democracy and policies that benefit the majority of Americans.

A stronger labor movement, for example, would benefit Wisconsinites by helping to lead the charge for a higher minimum wage.

- The 15 states with the highest union density all have minimum wages above the federal minimum.

- Wisconsin has kept its minimum wage at the federal minimum of $7.25 per hour, which has not increased since 2009 and has lead to six years of declining purchasing power for Wisconsinites who make the minimum wage.

- Wisconsin state law prohibits localities from acting on their own to raise the minimum wage within their borders.

- In contrast, Minnesota’s lawmakers stood up for workers in 2014 and increased the state’s minimum wage, which is currently $9.00 per hour for large employers and will increase to $9.50 in August 2016.

Wisconsin’s middle class would greatly benefit from stronger unions. Federal and state policymakers should make it easier, not harder, for workers to collectively bargain.

Brendan V. Duke is a Policy Analyst for the Middle-Out Economics project at the Center for American Progress. Alex Rowell is a Research Assistant with the Economic Policy team at the Center.