In the lead up to the release of the latest gross domestic product (GDP) report, there are increasing indications that the Trump administration has pushed the Federal Reserve into stepping on the brakes, and the Fed is about to step on them harder. After September’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, the federal funds rate, which the central bank uses to set monetary policy, was up 1.5 percentage points since President Donald Trump was elected. At least one more increase in December—which financial markets overwhelmingly predict will occur—will be the fifth hike since President Trump announced that he would appoint Jay Powell as Fed chairman.

Analysts will be poring over tomorrow’s GDP report as well as the FOMC’s upcoming statements for indications of what to expect over the next few months—but the effects of higher interest rates are already evident in households across the country. When the unemployment rate is low, it is historically the role of the Fed to slow the economy down to prevent inflation or asset bubbles by raising interest rates. History, however, can be a misleading guide to the present. There remains little sign of inflation and puzzlingly slow wage growth, weakening a key rationale for higher interest rates. There is also a less-widely discussed case for slowing interest rate hikes: Household debt looks different today than it has at any period on record, and it is not clear what risks will emerge as the Fed raises interest rates.

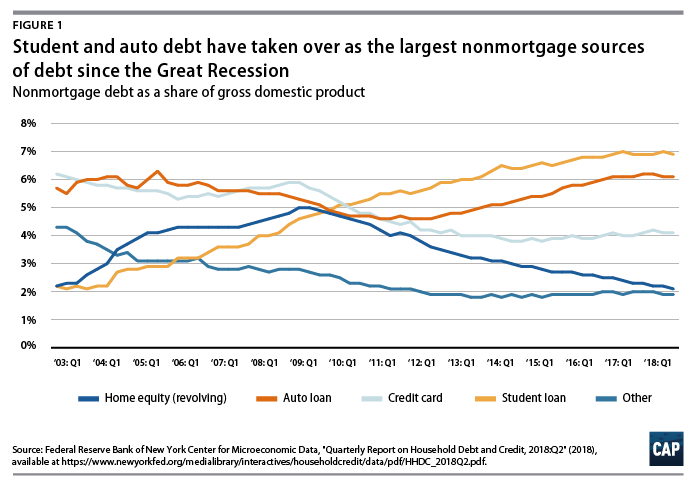

Housing debt remains the overwhelming majority of debt that families hold. The good news is housing debt is in a better place—along affordability, risk, and consumer protection dimensions—than it was before the Great Recession—a pretty low bar, but an indication that housing is unlikely to be the catalyst of the next crisis. What is different today is the outsized importance of household spending in maintaining economic growth and the rise in other forms of household debt since the recession.

Much ink has been spilled on the risks of subprime auto loans and the burden of student debt, but policymakers have generally been dismissive of the risks that these loans pose. There is some reason to worry that there is too much complacency about these risk factors: While auto loans have been relatively more risky since about 2000, they haven’t previously been at the forefront of financial risks. The student debt picture remains bleak for many borrowers and is arguably more worrisome from a macroeconomic perspective today than it was five years ago.

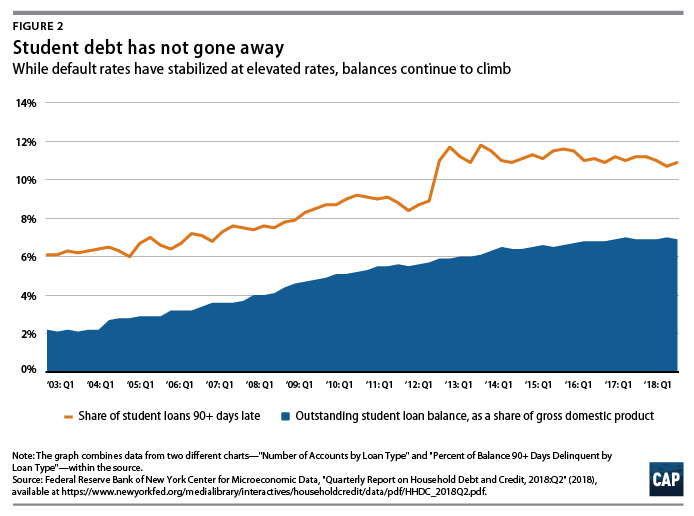

While student debts have stopped rising as fast as they did at their peak around 2005, they remain a burden on families and have little historical precedent. Demographics may have played a role in the rise of student debt, but they should also be turning into a tailwind by now as the millennial wave ages out of traditional schooling years. Even with an economy near full employment, student loan default rates remain stubbornly high.

Key student and auto loan concerns

Where the reduction in adjustable-rate mortgages means fewer households are directly exposed to rising borrowing costs, the economy-wide risk of higher borrowing costs may still remain quite high because student loan debt—currently $1.5 trillion nationally—is both a significant part of the economy and potential blind spot.

Student loans don’t pose the financial stability risks that mortgages pose because they are not as securitized or traded. Rising student loan burdens could, however, place real limits on households’ ability to support an economy that remains unusually reliant on consumer spending. There are also much less data about student loans than there are about other forms of debt, and it’s difficult to obtain public data on how much student debt is held at variable rates as well as what the overall reduction in disposable income would be from rising student loan costs.

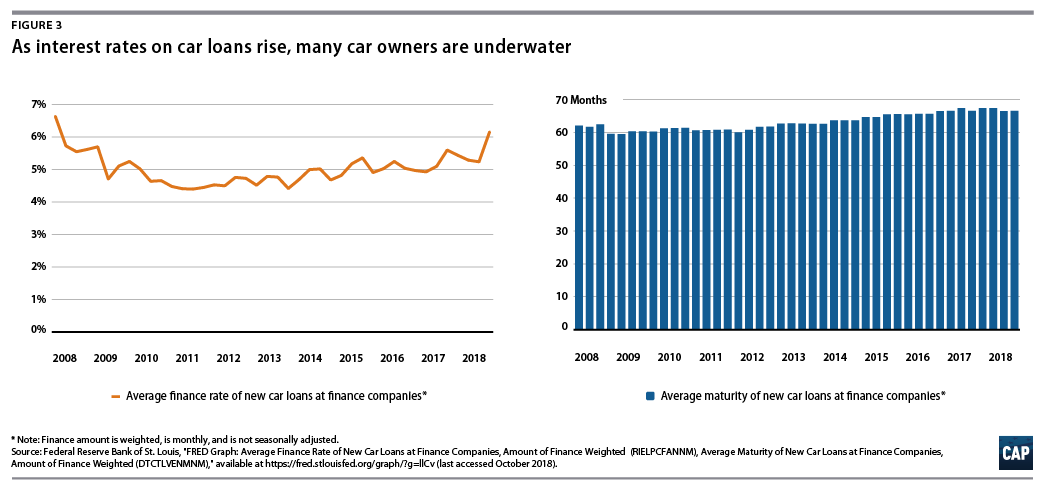

Auto loans are also a new risk factor for both households and the auto sector. Low-rate loans are nothing new, but the length of loans offered has risen to levels that have alarmed industry watchers. The average auto loan today is about 66 months, with loans of up to 8 years or more now available. These longer-term loans have become routine and mean many borrowers remain upside-down on their car payments—meaning borrowers’ cars are worth less than their remaining loan balances—for years after purchase. According to Equifax, nearly three-fourths of new car loans are between 5 years and 8 years long, while 60 percent of used car loans are 5 years to 7 years long, up considerably from prerecession levels.

The risks of auto defaults may be significant for some lenders and even automakers, but the new risk is on the consumer side—especially among subprime borrowers. With one-third of trade-in car payments upside-down and some lenders planning for subprime default rates as high as 1 in 3, the markers of financial fragility are familiar. However, because so many Americans lack access to transit and auto lenders can seize vehicles after short delinquency periods, the possibility of cascading risks to households may be much higher than in previous expansions.

If a worker loses her job and misses a credit card payment, she may face financial penalties. But if she misses car payments, she can lose her car—with repossession coming quickly if her loan is through a subprime lender. Even in a labor market with plenty of vacancies, finding a new job without a car can be significantly more difficult. Shocks that reduce mobility are a source of economic risk that are poorly understood, and some researchers have suggested spillovers from high gas prices were a major factor in touching off the housing crisis. Economists are starting to pay more attention to shakier auto loans as a risk factor, but the bulk of concerns have been on the corporate side, where the risk is more conventional, rather than on the household side, where the risk doesn’t fit existing templates as well.

Housing debt

The United States is currently $9 trillion in housing debt, with slightly less than $2 trillion in new mortgages in each of the past three years. While fewer borrowers are underwater, low down payments remain the norm, and it is possible that lower house prices could reverse some of the gains made in bringing down default and foreclosure rates. It is certainly true that negative equity has declined considerably, but the median home buyer in 2017 and 2018 would likely be underwater if home prices fell by 10 percent.

These risks are relatively normal, and very few experts would claim homeowners are at anywhere near the level of risk that they were prior to the 2008 financial crisis. Many mortgages are locked in at low rates, so it is uncertain what will happen to housing prices and homeowner mobility going forward. With rates up 1.5 percentage points, a $300,000 mortgage costs about $250 more a month to pay back than it did two years ago.

The housing crisis has made policymakers wary of a housing price collapse, but the recovery has made many Americans far more worried about housing affordability. As an economy, the United States is not building as much housing as needed, with residential investment still falling short in spite of a huge tax cut last year. Between households that are still recovering from the unprecedented equity hit they took during the recession and the trillions in mortgages at fixed, low rates that followed, many homeowners face a large wedge between their current home affordability and the payments they would face if they moved. If higher mortgage costs make families less able or willing to move, housing supply could become even more of a concern.

Businesses are already aware that interest rates are going up, but the discussion around workers has largely been about wages and unemployment, even as the effect of higher interest rates on households has started to bite. Much less is known about what comes after the next round of rate hikes than the FOMC’s confident slowing of the economy would suggest—and that is a major concern.

Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center for American Progress.