The United States is currently experiencing one of the longest periods of economic expansion in its history.1 However, the expansion has not reached all households and many are struggling to cover the costs of basic emergencies.2 At the same time, economic growth appears to be slowing, and there are warning signs that a recession is possible in the near future. While downturns are difficult to predict, policymakers have a responsibility both to assess whether the country is prepared for the next recession and to implement approaches to protect Americans from the worst outcomes.

Fortunately, the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government has a variety of tools available to help pull the national economy out of a recession. These tools generally fit into two categories. First, there is monetary policy, which is conducted by the Fed, the independent central bank responsible for setting interest rates, among other things. Second, there is fiscal policy, which is conducted by the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government. However, these tools may prove less effective in the next recession, in part because the Fed has less room to cut interest rates, its traditional tool to tackle downturns.3 And fiscal policy, while still potentially effective, relies on politicians’ willingness to use it in the right way, which has not always been the case. For example, during the Great Recession, Congress engaged in austerity measures, reducing spending well before the economy fully recovered.4

Automatic stabilizers are another tool that can help mitigate the effects of a recession. Enabled once the economy hits a downturn, these stabilizers—such as the expansion of unemployment insurance (UI)—are effective in helping stabilize the economy.5 For example, UI kept more than 5 million people out of poverty during the Great Recession and prevented 1.4 million foreclosures.6 Unfortunately, since the latest recession, states have reduced these benefits, thereby diminishing their positive effects.7

This issue brief begins by outlining the lasting effects of the Great Recession, including which generations were most affected and in what ways. It then outlines why many experts fear the next recession is right around the corner and assesses whether policymakers are prepared to tackle it. Finally, it highlights how to successfully combat this recession when it occurs.

Given the fiscal and monetary climate facing the country—including a lower federal funds rate and limited use of fiscal policy—automatic stabilizers will be crucial for preparing the country for the next recession.

The permanent recession

Although the economy has been growing since 2009, even those who have benefited from this growth are still feeling the effects of the Great Recession. While recessions are harmful in a variety of ways—most significantly because people lose their jobs—they also leave a permanent mark on people’s consciousness. For some, there is the pain of being forced to take a lower-level job. For others, jobs are not even available.

Several generations have been adversely and permanently affected by the Great Recession. Millennials, many of whom had only recently entered the labor market at the time of the recession, have altered their behavior because of the downturn, delaying big purchases such as houses.8 Baby Boomers with nest eggs wrapped up in the stock market saw their savings nearly wiped out.9 Homeowners of all ages were and continue to be profoundly affected.

Economists Heather Boushey, Ryan Nunn, Jimmy O’Donnell, and Jay Shambaugh found that the Great Recession led to long-term damage to both businesses and households.10 In their report, “The Damage Done by Recessions and How to Respond,” the authors demonstrated that the employment-to-population ratio has not recovered since 2008 and that many people have permanently left the labor force. Moreover, Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel found that those who graduated from college during the recession have ended up with permanent wage losses.11 A new working paper by U.S. Census Bureau economist Kevin Rinz finds that Millennials have not only not recovered their earnings losses from the Great Recession but also that their earnings may never recover.12 He finds that from 2007 to 2017, Millennials lost 13 percent of actual earnings due to the Great Recession, while members of Generation X and Baby Boomers lost 9 percent and 7 percent, respectively.

Because of this so-called permanent recession, the distribution of the benefits of the latest expansion has not reached certain demographics or geographic regions. And those who have benefited from recent growth have been heavily concentrated at the top of the economic pyramid. For example, nonmetropolitan counties have not fully recovered, as economic growth has been more heavily skewed toward metropolitan counties. Claims that the labor market is tight are therefore premature;13 many groups are not experiencing the outcomes indicative of a tight market. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell recognized this fact when he said, “To call something hot, you need to see some heat.”14 He also pointed to meager wage growth as evidence that labor markets are not “hot.”

Recession concerns

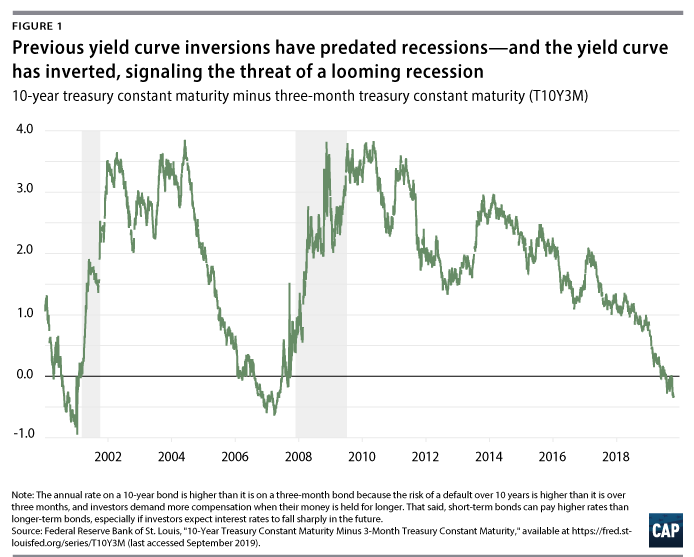

Recently, many experts have focused on the economic headwinds now facing the country following 10 years of unprecedented growth.15 Yet while economists carefully watch indicators such as gross domestic product and the unemployment rate, recessions are notoriously difficult to predict. These same economy watchers also focus on some alternate measures with a strong record of predicting when the next recession will hit. Perhaps the most watched measure at the moment is the yield curve. This measures the difference between the 10-year Treasury rate and short-term interest rates, such as two-year Treasury bonds or three-month Treasury bonds.

The signals of a possible recession that the yield curve provides are fairly intuitive. Normally, the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond exceeds the interest rate on a three-month bond because these rates incorporate growth rates: Observers expect that for as long as growth occurs, further time horizons will result in higher interest rates. But this normal relationship between long- and short-term bonds can flip, with short-term bonds paying higher rates. This is especially true if investors expect interest rates to fall sharply in the future. Historically, when the short-term interest rate yield has risen above the yield for the 10-year Treasury note for an extended period, a recession has followed.16 Therefore, most analysts think of an inversion as a measure of sentiment about where the economy is headed.

Figure 1 shows that the yield curve inverted prior to both the 2001 recession and the Great Recession. It also shows that at this moment, the three-month Treasury note yield exceeds that for the 10-year Treasury note. Given the current inverted yield curve, and its strength in predicting previous recessions, should policymakers be concerned? The Federal Reserve Bank of New York calculates recession probabilities and predicts that there is a 31.4 percent probability of a recession in the next 12 months. Simon Moore, chief investment officer at Moola, believes that observers should start being concerned when the gap between long- and short-term notes is large, at around -1.2 percent.17 It is important to note, however, that there is no evidence that a yield curve inversion is causal, so an inversion by itself will not cause a recession.

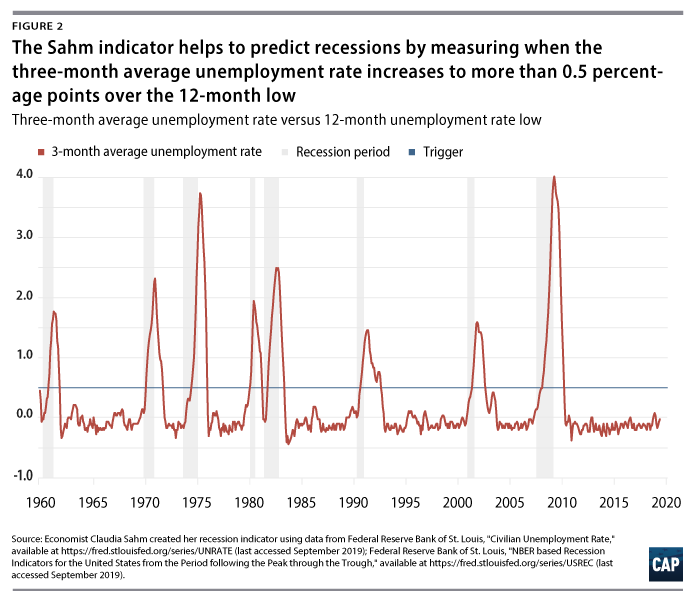

In the past, it has not always been clear even when a recession has already begun. To improve policymakers’ ability to take timely action to counteract recessions, The Hamilton Project has developed a new measure designed to signal when a recession has arrived.18 In a report for The Hamilton Project, “Direct Stimulus Payments to Individuals,” Fed economist Claudia Sahm created a new measure for an automatic stabilizer that would trigger direct payments to individuals when the three-month average unemployment rate jumps 0.5 percentage points above the 12-month low. Figure 2 plots the indicator, along with the 0.5 trigger level and recessions from 1973 to the present.

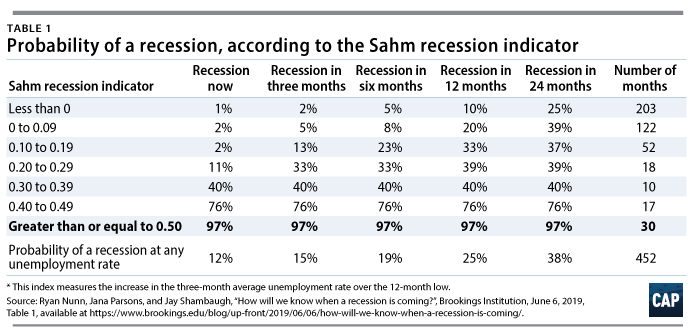

Using Sahm’s measure, this figure clearly indicates that the United States is not already in a recession, as the indicator has stayed consistently below the 0.5 trigger level since the end of the Great Recession. This indicator focuses on the spike in the unemployment rate above its 12-month low. Therefore, it can be used to predict the probability of a recession. (see Table 1)

For the most recent month, the three-month average of the unemployment rate is 3.7, which is 0.07 percentage points above the 12-month minimum, which in the table corresponds to a 2 percent to 8 percent probability of a recession in the next six months. While the yield curve inversion gives pause to policymakers, the Sahm indicator shows that a recession may not manifest itself in the near future.

Combating a recession

In the case of a recession, policymakers need to know both the tools available to them to combat the downturn and the effectiveness of those tools. Both monetary policy and fiscal policy exist to guide the economy in both good times and bad.

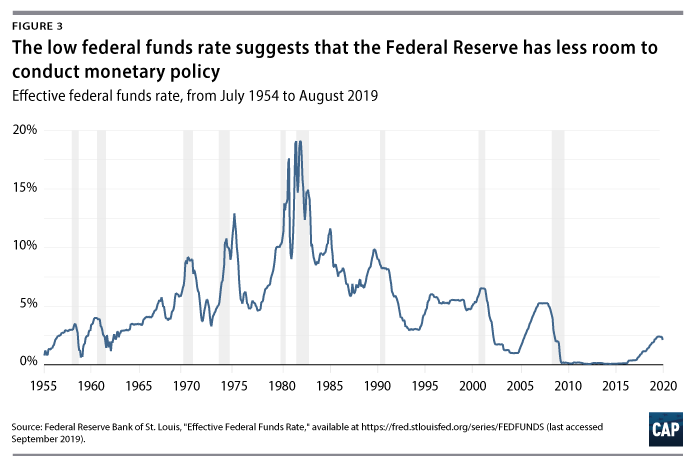

Fiscal policy, in the hands of the legislative and executive branches, entails adjusting taxes and government spending to either boost the economy or to curb economic activity to limit inflation. Monetary policy by the Fed entails adjusting the federal funds rate to regulate economic activity. Figure 3 shows the rate since 1955.

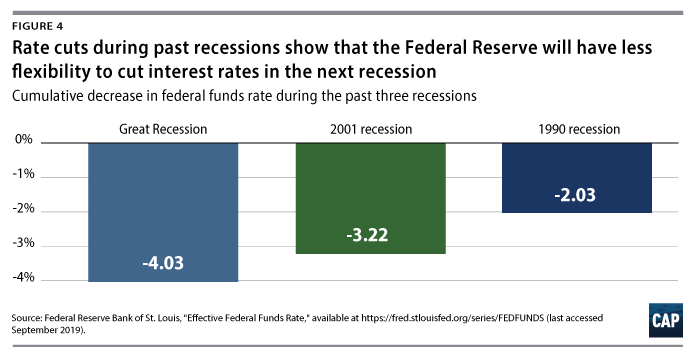

Figure 3 shows that during recessions, the federal funds rate was decreased in order to spur the economy. The rate reached a peak of nearly 20 percent in the 1980s when then-Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker aimed to combat inflation. It has not exceeded 7.5 percent since the early 1990s, and the inflation rate has held constant. Figure 4 shows the level of rate cuts during the past three recessions—in 1990–1991, 2001, and 2008–2009—to show how much the Fed has reduced rates to combat a recession.19

Figures 3 and 4 show that at this point, the Fed cannot engage in similar rate cuts, since the current rate is 2 percent. As a result, monetary policy is likely to be less effective in combating the next recession.20

Figures 3 and 4 show that at this point, the Fed cannot engage in similar rate cuts, since the current rate is 2 percent. As a result, monetary policy is likely to be less effective in combating the next recession.20

Fiscal policy will therefore be crucial in combating any coming downturn as long as interest rates remain low—and many experts predict they will stay low for quite some time.21 While there is reasonable concern that Congress will not act in a timely manner for fiscal policy to be maximally effective, the United States has certain policies that are triggered automatically in the event of a recession. These interim policies provide a buffer between when the recession occurs and when fiscal policy gets implemented.

More importantly, over the past decade, plenty of evidence has accumulated that demonstrates the economic costs of not implementing a sufficiently large fiscal stimulus. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the U.S. government implemented austerity measures in the second quarter of 2011—far too soon—even though the unemployment rate was still around 9 percent and the reverse was actually necessary.22

Some of the most important tools available to combat a recession—automatic stabilizers—do not require any government action to take hold.23 These work without congressional action and inject funds into the economy in the event of a downturn, either through transfer payments or tax reductions. Some examples include progressive income taxation, the Earned Income Tax Credit, unemployment insurance, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).24 These programs work as automatic stabilizers because they are tied to income and are implemented when incomes fall. SNAP and UI were effective as automatic stabilizers during the Great Recession.25 Yet while these programs have previously been effective automatic stabilizers, their effectiveness should be strengthened and improved by congressional action.

Unemployment insurance

The UI system is a crucial automatic stabilizer that provides a soft landing for individuals who face layoffs or experience joblessness. While it is a state-run program, the federal government can supplement it during a recession. The purpose of UI is to partially replace lost wages to assist unemployed job seekers as they try to regain employment. To be eligible for UI benefits, the unemployed individual must not have lost their job for cause, must have a sufficient earnings history, and must have paid into the system through their employer.26 In periods of high unemployment, the federal government has provided more assistance through the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program and even more in high-unemployment states through the Extended Benefits (EB) program, though these programs are not automatic and expired in 2013.27

Since the end of the last recession, many states have decreased UI payouts through dramatic and historically unprecedented reductions. These include reductions in the number of weeks of available benefits, cuts to wage replacement rates, stricter eligibility requirements, direct benefit cuts that reduce how much of workers’ prior wages UI can replace, and new disqualifications. These cuts occurred instead of increasing the revenue from employer taxes to replenish the state programs’ trust funds.28 Despite the urgent need to prepare the UI system for the next recession, state policymakers continue to undermine it. For example, as recently as May 2019, a Republican-sponsored bill was passed in Alabama that reduced the duration of unemployment benefits below the current 26-week limit.2 Reducing the maximum duration below this threshold is particularly counterproductive when the stabilizing effect of these benefits is needed most.

Policymakers should instead shore up UI to make it more effective by increasing the amount of the benefit and its duration. For example, states should all maintain the 26-week maximum duration. States should also ensure that as they automate their UI program, there are resources for job seekers to easily learn the process and to access benefits.29 There are also structural issues with the system that should be fixed: States should expand reemployment programs, harmonize benefit amounts so they are consistent from state to state, and expand eligibility rules.30

The federal government also has a potential role in strengthening UI by introducing solvency requirements for trust funds, which states have struggled to replenish since the Great Recession.31 Economists Gabriel Chodorow-Reich and John Coglianese outline ways to improve the UI program in their report “Unemployment Insurance and Macroeconomic Stabilization.” They argue that policymakers should expand eligibility, reform the EB program by making it fully federally financed and by creating new triggers, and increase the weekly benefit amount to $50.32 Implementing these fixes and reforms will strengthen the UI program and make it a more effective automatic stabilizer—a crucial step to help avoid another Great Recession.

Conclusion

A recession is coming, whether this year, next year, or soon after. The country needs to be prepared, regardless of when it hits. The U.S. government needs to engage all the tools at its disposal, but many monetary and fiscal policy tools may be less effective in the next recession than they were in the last. Fortunately, automatic stabilizers provide a solution and a soft landing for those hit hardest by a downturn and struggling to bounce back after an unemployment spell.

Therefore, it is critical to strengthen automatic stabilizers such as UI and combat any state’s efforts to make these tools less effective through benefits cuts, eligibility restrictions, and onerous work requirements. The time to act is now, or the next recession will hit harder than the last.

Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress.