New data released today by the U.S. Census Bureau show that four years into the economic recovery, there has been some progress in the poverty rate as it fell from 15 percent in 2012 to 14.5 percent in 2013, with gains especially strong for children, whose poverty rates fell by nearly 2 percentage points. There was no statistically significant improvement, however, in the number of Americans living in poverty. The share of families struggling on the economic brink also remains elevated, with about one-third—33.9 percent—of Americans just one paycheck, sick child, or broken-down car away from poverty. Women, people of color, and young workers are among those hardest hit by the recession and the subsequent weak recovery.

These data further confirm what many working families experience on a daily basis: The economy is off kilter, with gains from economic growth concentrated at the top, while low- and middle-income families continue to struggle with stagnant incomes and barriers to employment.

Unfortunately, these trends are not unique to this particular economic recovery. In the six years between the end of the 2001 recession and the beginning of the Great Recession, low- and middle-income families experienced few gains from economic growth. In fact, the incomes of low- and moderate-income families were actually lower in 2007 than in 2000, and after hitting its lowest point in several decades, the poverty rate increased from 11.3 percent in 2000 to 12.5 percent in 2007. These negative trends occurred despite the fact that the unemployment rate was only moderately higher in 2007, at 4.6 percent, than it was in 2000, at 4 percent, with declining and stagnant wages being a key culprit.

In this context, here are three things you need to know about the new data for 2013 and how they affect looming policy choices:

- The economic recovery is not translating into broader income growth, keeping millions of families trapped in economic insecurity.

- Young workers are still struggling to stay afloat, despite being more educated than previous generations.

- Fifty years after the Civil Rights Act, there has been some progress for women and people of color, but persistent racial, ethnic, and gender disparities remain.

These trends and their implications are examined below.

The economic recovery is not translating into broader income growth

Adjusting for inflation, median family income stayed flat between 2012 and 2013 and remained lower than in both 2007 and 2000. This decline in family incomes is due in large part to stagnant wage trends.

Given that the vast majority of Americans—including those at the bottom of the income scale—rely on their paychecks and work-related benefits as their primary source of income, wage stagnation is an important variable linked to the lack of progress on improving economic security and cutting poverty. As economists at the Economic Policy Institute have recently documented, real wage growth has been negative since 2000 for workers in the bottom 30 percent of the wage distribution and basically stagnant for workers in the middle. Only workers with incomes in the top 5 percent have seen solid gains.

Flat wages mean that low- and middle-income families often must borrow to keep pace with the rising costs of basic goods and to afford pillars of family economic security such as child care and health care. This leaves families more vulnerable to economic shocks, which can send them spiraling below the poverty line once again. Income inequality is a destabilizing force in our economy, leaving large swaths of people subject to chronic economic insecurity and debt.

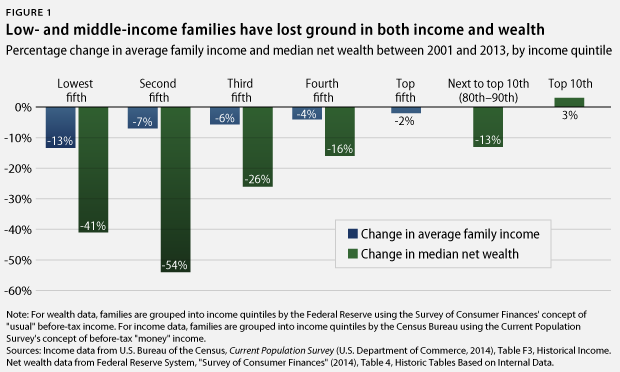

Moreover, as Figure 1a shows, increasing income inequality has exacerbated the increase in wealth inequality, with families in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution experiencing particularly large declines in net wealth between 2001 and 2013.

Absent policy action, these trends are likely to continue. In August 2014, low-wage industries, such as food services, retail, long-term care, home health care, and temporary help, comprised 37 percent of new jobs in the private sector. Fortunately, there is evidence that establishing and strengthening basic labor standards is part of the solution. A recent Economic Policy Institute analysis showed that during the past year, real hourly wages declined for all workers except those in the bottom 10 percent of the wage distribution, with workers in states that raised their minimum wages accounting for the increase. This underscores that public policy—and specifically minimum-wage increases—have an important role to play in combating wage stagnation.

As the economy slowly recovers, improving job quality and boosting wages must be a central strategy to ensure that the gains of economic growth reach struggling families.

Young workers are still struggling to stay afloat, despite being more educated

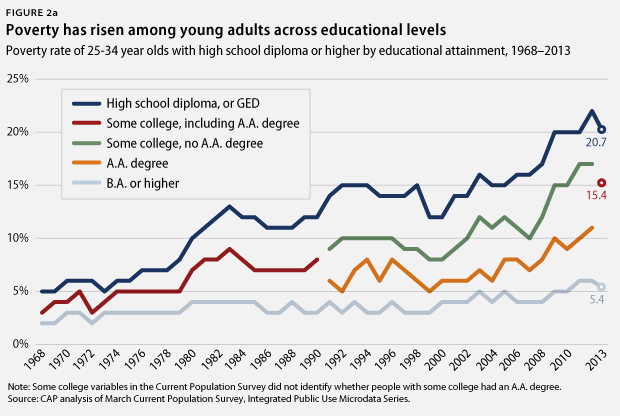

While children experienced significant declines in their poverty rates in 2013, these gains were less dramatic for youth transitioning to adulthood. According to the new Census data, 19.4 percent of people ages 18 to 24 had incomes below the poverty level last year, and young adults ages 25 to 34 did not see an improvement in their poverty rates, which were stuck at 15.8 percent in 2013. High poverty for these groups is particularly striking given their education levels. Young people today are much more educated than their counterparts 50 years ago. However, 18- to 34-years-olds today face higher poverty rates than those of the same ages and educational levels did 50 years ago. Figure 2a charts poverty trends for 25- to 34-year-olds by education level between 1968 and 2013. It shows, for example, that even poverty rates for young people with college degrees or more were about twice as high in 2013 than in 1968.

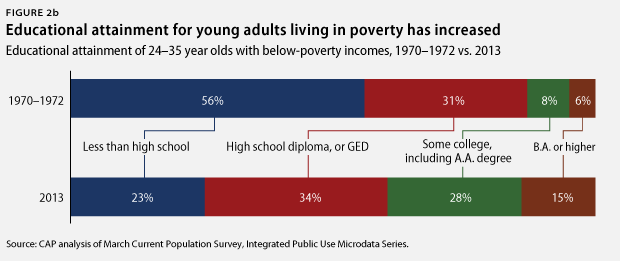

While some of this increase is due to continued high unemployment, there has also been a clear long-term trend toward higher poverty rates for young people at all levels of education. One of the consequences—shown in Figure 2b—is that the vast majority of young people living in poverty today have a high school diploma or more, and more than one-third have some postsecondary education, including 14.5 percent with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Higher education is still an important platform, making it possible for millions of Americans to join the middle class. As Figure 2a shows, the more education one has, the less likely he or she is to be poor, with workers who have at least a four-year college degree experiencing the lowest rates of poverty. However, without good jobs and good wages, the return that today’s young people see on their educational investment will continue to decline. Even more students will be saddled with outsized student-loan debts that will keep them from investing in home ownership, starting families, and affording basic necessities.

The high poverty rates of young people carry long-term consequences. Research that examined the prospects of college graduates who started their careers during recessions revealed that they were followed by lower wages over the roughly 15-year period data was available.

Improving the mobility and opportunities of young workers will require improving job quality. This can be done by raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour, adjusting it annually to keep pace with the costs of living, and enabling young workers without qualifying children to access the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC. Providing more avenues for young people to access employment, such as through expanding apprenticeships, and addressing their crushing levels of student debt through refinancing options can also help address high poverty rates among young people.

Despite some progress for women and people of color, persistent disparities remain 50 years after the Civil Rights Act

The poverty rate is too high across the board, but certain groups continue to face much higher risks of poverty and economic insecurity than others, including women and people of color.

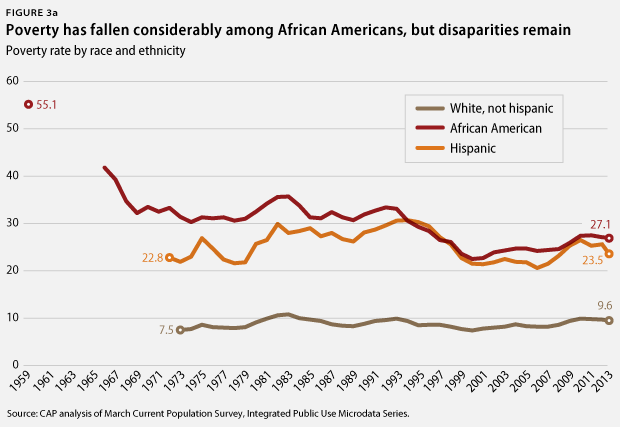

Fifty years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, it is important to acknowledge the progress that has been made in cutting poverty, particularly for African Americans. From 1966 to 2013, the share of the private-sector workforce comprised of people of color rose from 11.2 percent to 29.7 percent, and women’s share grew from 31.2 percent to 48.2 percent. As Figure 3 shows, black poverty rates fell from 55 percent in 1959 to 27.2 percent in 2013, due partly to greater civil rights protections and opportunities in the labor market. And Latinos were the only racial or ethnic group to see a statistically significant decline in their poverty rate in 2013.

That being said, Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans are still significantly more likely to live below the poverty line than white non-Latinos. People of color are more likely to live in neighborhoods and places with very high poverty rates, often for reasons related to systemic discrimination; to face employment discrimination; and to bear the brunt of policies that have led to mass incarceration. As with young people, their poverty rates remain relatively high despite considerable educational advancement. For example, based on our analysis of CPS data, in 1965, only one-third of working-age African Americans had a high school diploma or additional education; today, nearly 90 percent do. In short, plenty of work still needs to be done to ensure equal opportunity.

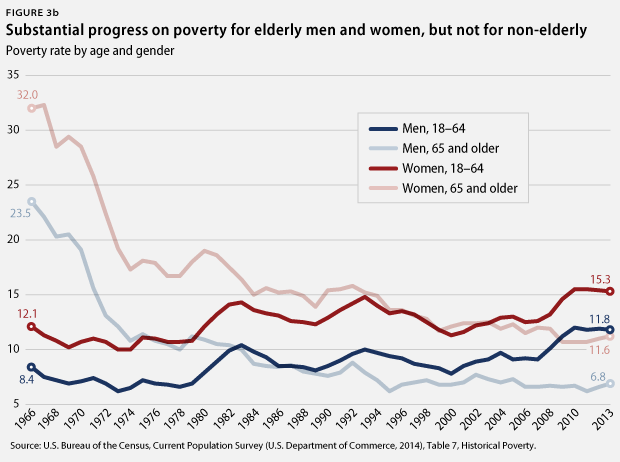

The story is more mixed for women. As Figure 3b shows, while elderly women’s poverty rates dropped from 32 percent in 1966 to 11.6 percent in 2013—a testament to Social Security and other federal policies’ effectiveness—the poverty rate for non-elderly women remains elevated. While the poverty gap between non-elderly men and women has narrowed some over time, this has more to do with the deteriorating economic positions of many men than with improvements for women.

These data do not take into account how the EITC, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, and certain other important elements of the safety net have improved the economic well-being of families, but they do provide a point of comparison in terms of income from work and cash benefits.

For women, basic labor standards and the workplace environment have not caught up to the reality of their central role in the labor market. The United States is the only developed country with no paid family and medical leave and no paid sick days, which forces workers to make impossible choices between work and family responsibilities. The lack of these family-friendly policies is an important factor of the persistent gender wage gap.

However, these disparities are not just problematic for women and people of color. They also affect our overall economy. By 2042, people of color will make up the majority of our workforce. Allowing racial and ethnic disparities to linger now will undercut our economic competitiveness in the future. Similarly, if we close the gender wage gap, we can cut the poverty rate of working women and their families in half and add nearly 500 billion dollars to our gross domestic product.

Conclusion

While the past decade has left low- and middle-income Americans behind, there are policy solutions that can reverse these trends. Raising the minimum wage to $10.10 per hour and indexing it to inflation would lift up to 4.6 million people out of poverty. Expanding the EITC for childless adults and lowering its eligibility age would allow more young workers to achieve economic stability. Policies such as paid family and medical leave, paid sick days, investments in child care and early education, and criminal justice reform would help close persistent racial, ethnic, and gender disparities while improving our economy.

Our nation cannot afford another year of stagnation. These data should serve as a wake-up call that policy action is needed to provide greater economic stability and opportunity for all Americans.

Melissa Boteach is the Vice President of Half in Ten and the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Shawn Fremstad is a Senior Fellow at the Center.