On Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release its August employment report. After two months of growth that exceeded predictions, greater numbers in August would confirm that the economy is still picking up steam in the wake of the Great Recession. Total employment continues to increase, with 255,000 jobs added in July and average hourly earnings having increased by 2.6 percent since this time last year. However, the unemployment rate has remained steady at less than 5 percent—a sign that significant slack in the labor market remains.

Given this relatively good news, some have argued for an early interest rate increase. This past Friday, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen weighed in on the debate, spelling out competing narratives about how the Fed should proceed in the coming months. Looking at the continued resiliency of the economy, she noted, “[T]he case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months.” However, she also acknowledged persistently low inflation and other measures by which the economy is still short of the Fed’s stated benchmarks for rate increases.

As the Center for American Progress highlighted this past month, low inflation and the beginnings of a much-needed real wage growth signal strongly that the economy does not yet need a rate increase. Furthermore, unemployment remains troublingly high for certain demographics of workers. While this time of year marks the first day of classes and/or the first day of full-time work for many U.S. teens, this demographic has been largely left behind on the gains of the economic recovery.

Unemployment and teen workers

For teenagers who are in the labor force, the cost of continued elevated youth unemployment is high: Research shows that early periods of unemployment result in lower lifetime wages due to forgone work experience and human capital building opportunities. For example, a 2013 analysis by CAP found that the nearly 1 million young Americans who experienced long-term unemployment during the Great Recession will lose a staggering $20 billion in earnings over the next decade. During the Great Recession, young workers were especially hard hit. For example, the unemployment rate for teenagers ages 16 to 19 reached a historic high of 27.2 percent in both October 2009 and October 2010.

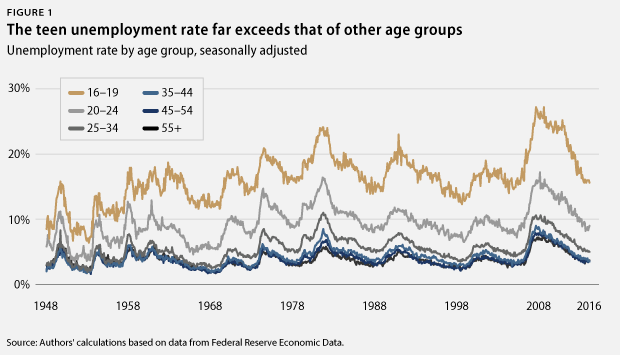

Today, the unemployment rate for teens ages 16 to 19—which is currently more than 15 percent—is three times higher than the rate for workers ages 25 to 34. Additionally, although the teen unemployment rate seems to have returned to pre-recession levels, that does not necessarily signify full employment. Instead, this level of unemployment may be higher than what can be justified by the frictions of job transitions or voluntary unemployment.

Youth unemployment is a result of multiple factors. It may reflect a skills mismatch between young workers and local employers or a lack of adequate qualifications to prepare young people for available jobs. Teen unemployment is also higher than the overall rate because teenagers are necessarily less educated and lower levels of education are correlated with higher rates of unemployment. Monetary policy—such as interest rate adjustments—also plays a role, as premature tightening policies may pull the rug out from teen employment, exacerbating these existing barriers.

African American teens are unemployed at higher rates

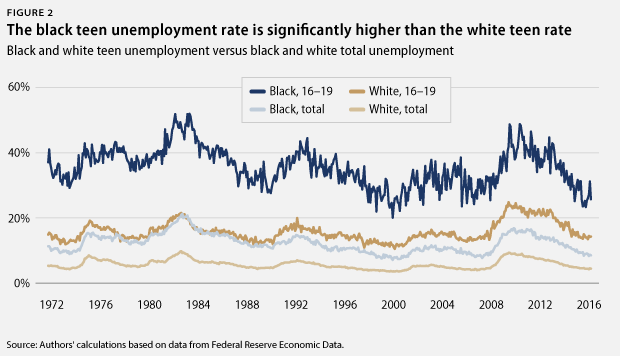

Teen unemployment is most costly for young black workers, and the disparity cannot be explained by other racial demographics’ higher college enrollment. In July, the unemployment rate for black teens was 25.7 percent—almost twice the 14.2 percent rate of their white counterparts. Both teen unemployment rates were higher than those of the total black and white labor force populations, but black teen unemployment outsized the rest.

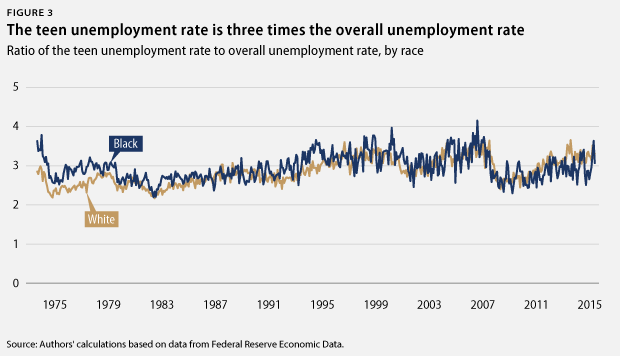

Teen unemployment rates for both races—black and white—were more than three times the respective overall unemployment rates for each race. The ratio between teen unemployment and overall unemployment follows a similar trend for both racial demographics. However, since the overall black unemployment rate is higher, the teen unemployment rate is also substantially higher, signifying constrained economic mobility for this demographic of workers.

Higher unemployment rates have negative long-term economic implications. Black workers experience scarring effects in which unemployment itself increases the likelihood of experiencing future periods of unemployment and lower lifetime earnings due to discrimination against workers who experience periods of unemployment. As such, black workers also face more long-term unemployment, which puts them at greater risk for dropping out of the labor force altogether.

Black men have the highest teen unemployment rates

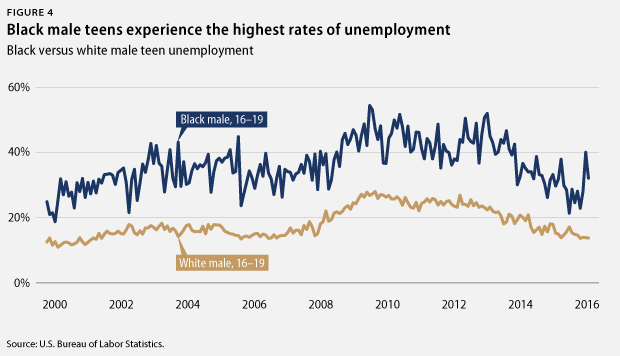

Young black men have higher unemployment rates than both young white men and young black women. Overall, black men ages 16 to 19 have higher unemployment rates than black women in the same age group. Since the Great Recession, black male teen unemployment has spiked five times and now sits at more than 30 percent. Moreover, the unemployment rate for black men ages 16 to 19 is about twice the rate of their white counterparts. In the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics July estimates, black male teen unemployment was 32.3 percent as compared to 13.9 percent of white male teen unemployment. However, it should also be noted that there is significant month-to-month variation in these figures due to the small samples of these demographics in the data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Teen labor force participation has declined

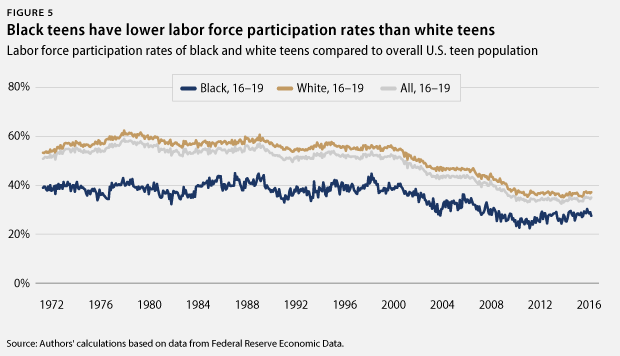

The labor force participation rate for black and white teens has declined since the late 1990s. This trend aligns with a significant increase in school attendance over the past 20 years. However, there are long-running disparities between the labor participation rates for black and white teens, as black teens have had a considerably lower labor force participation rate than white teens. In July, the labor force participation rate for white teens was 37.4 percent, while the rate for black teens was 27.7 percent. The overall racial disparity is similar for both young men and young women, as well.

This lower labor force participation rate is explained by a higher percentage of black teens who are either not working, not receiving professional training, or no longer enrolled in school. A Pew Research Center analysis of Current Population Survey data shows that 22.2 percent of black teens ages 16 to 19 fall into this category, as compared with only 15.8 percent of white teens. The Brookings Institution also found that a higher proportion of black teens are disconnected from the labor force, which Brookings defines as “not working or in school, with less than an associate degree, living below 200 percent of the poverty line, and not living in group quarters such as dorms or correctional facilities.” While only 4.6 percent of teens ages 16 to 19 are disconnected overall, 7.6 percent of black teens are disconnected.

In addition to racial discrimination, black people face many structural barriers to employment. For example, they experience labor market segregation that pushes them into lower paying jobs with fewer benefits and disproportionally higher rates of mass incarceration. Similar to higher rates of unemployment, lower labor force participation can lead to prolonged economic effects and reduced economic well-being over the course of an individual’s lifetime.

Conclusion

As the U.S. labor market improves, it is clear that not all workers are faring equally. After a stretch of consistently good monthly employment reports, policymakers should ensure economic growth remains robust enough to benefit the demographics that are all too often left behind. Higher unemployment and lower labor force participation affect not only an individuals’ current economic status but also their long-term well-being.

Teenage employment is not simply about getting a summer job to earn some extra spending money—it can build long-term earnings potential for young workers. Higher rates of unemployment for teens ages 16 to 19 are not a new phenomenon, but cyclical variations and disparities based on race and gender are cause for concern. Black teenagers—specifically young black men—are at a particular disadvantage.

Despite the benchmark improvements in the monthly labor market data, there is still a need for both broad progressive economic policy to give all workers a fair shot, such as appropriate Fed policy and directed policy to help young black workers in particular. These steps matter both for the economy overall and the opportunities that can be created—or destroyed—for individual young workers.

Kate Bahn is an Economist at the Center for American Progress. Annie McGrew and Gregg Gelzinis are Special Assistants for the Center’s Economic Policy team.