Download this issue brief (pdf)

Read this issue brief in your web browser (Scribd)

In 2009 the Center for American Progress released “The New Breadwinners,” a chapter in The Shriver Report: A Woman’s Nation Changes Everything. The report describes how women’s movement out of the home and into the paid labor force has changed everything about how our families live and work today. While our lives have changed as a result of this dramatic transformation, the institutions surrounding us have not necessarily kept up. In “The New Breadwinners,” CAP Senior Economist Heather Boushey illustrated how women have made great strides and are now more likely to be economically responsible for themselves and their families, but there is a still a long way to go.

In this brief we update the numbers from “The New Breadwinners” to reflect the most recent data available based on family income, race, age, and motherhood, and show how the trends identified in the 2009 piece have only grown stronger in the ensuing years.

We find that there are more wives, and women generally, supporting their families economically now than ever before—and there could not be a more important time to ensure that working women receive the pay they deserve. The typical woman only earns an average of 77 cents to the male dollar. It is not difficult to imagine how many more women would be breadwinners—and how much better off our families would be—if the gender wage gap were closed.

Overall increase in women breadwinners and its effects on society

In July 2009, just after the National Bureau of Economic Research says the recession technically ended, women made up half (49.9 percent) of all workers on U.S. payrolls for the first time in our nation’s history. While part of this was undoubtedly due to steep job losses by men, even now in the midst of the so-called “Man-covery,” women still comprise about half of U.S. payrolls (49.3 percent as of February 2012).

Some groups of women, particularly women of color, immigrants, and low-income women, have always had high levels of labor force participation. But in 1969 women were only about a third of the workforce (35.3 percent). Women’s increased labor force participation has been partially about personal choices and partially about economics, but regardless of the motivating factor, it is not something that is likely to change. The following analysis will show that women’s wages are making up ever-larger portions of family budgets, making a large-scale departure from the paid labor force unlikely.

As a result of this transformation, most children today are growing up in families without a full-time, stay-at-home caregiver. In 2010, among families with children, nearly half (44.8 percent) were headed by two working parents and another one in four (26.1 percent) were headed by a single parent. As a result, fewer than one in three (28.7 percent) children now have a stay-at-home parent, compared to more than half (52.6 percent) in 1975, only a generation ago.

The recession led to higher job losses among men, which meant that in a greater number of families, the husband was unemployed while the wife supported the family. In 2010, for the first time in decades, unemployment was concentrated among husbands rather than wives.

In no small part due to higher male unemployment, alongside the longstanding trends, in 2010 in nearly two-thirds (63.9 percent) of families with children women were either breadwinners or co-breadwinners. (see Figure 1)

While this overall rate has not changed much since the last economic peak in 2007 (when rates stood at 62.8 percent), it masks a more dramatic trend. The percentage of mothers who are co-breadwinners—those working wives bringing home at least 25 percent of their family’s total earnings but less than their partner— has actually fallen from 24.4 percent in 2007 to 22.5 percent in 2010. At the same time the rate of breadwinners—those working wives earning as much or more than their partners and single mothers providing the sole income for their family—has increased from 38.4 percent in 2007 to 41.4 percent in 2010.

For the remainder of this brief we dig a little deeper into these numbers and see how this trend breaks down by family income, race, age, and motherhood.

Family income

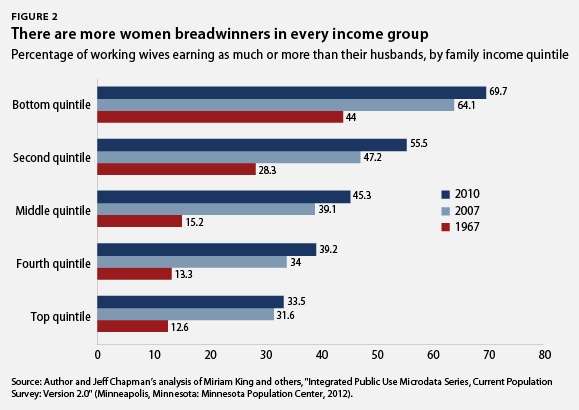

The percentage of working wives earning as much or more than their husbands has increased across all income groups. (see Figure 2) A third (33.5 percent) of working wives are breadwinners in families with incomes in the top 20 percent of all families (not just married-couple families), up from just less than a third in 2007 (31.6 percent) and only one in eight (12.6 percent) in 1967.

Breadwinning wives are even more common in families with lower incomes. Seven in 10 (69.7 percent) working wives earn as much or more than their husbands in the bottom 20 percent of income distribution for all families. And about half (45.3 percent) of working wives are breadwinners in families in the middle of the income distribution, up from 4 in 10 (39.1 percent) in 2007 and only 15.2 percent in 1967.

Race and ethnicity

The percentage of wives earning as much or more than their husbands also increased for all racial and ethnic groups, with similar gains for all groups. (see Figure 3) Among African American families, more than half (53.3 percent) of working wives earned as much or more than their husbands in 2010, up from 45.7 percent in 2007, and marking a dramatic increase from 1975 when 28.7 percent were breadwinners.

And about 4 in 10 working wives were breadwinners in 2010 for both white (41 percent) and Hispanic (40.1 percent) families. This is nearly double the rates from 1975.

Age

Working wives of all ages are likely to earn as much or more than their husbands, though the percentages increase as women age. (see Figure 4) In 2010 more than a third (36.8 percent) of working wives under the age of 30 were breadwinners, up from 31.9 percent in 2007 and only 14.8 percent in 1967. Working wives between the ages of 30 and 44 had roughly the same odds of being a breadwinner (37 percent) in 2010 as younger women, up from 31.7 percent in 2007 and only about 1 in 10 (11.9 percent) in 1967. And about 4 in 10 working wives between the ages of 45 to 60 earn as much or more than their husbands, a small increase from 2007 (39.7 percent) though significantly more than the 24.1 percent who were breadwinners in 1967.

Motherhood

Finally, roughly a third of all working mothers earn as much or more than their husbands regardless of maternal age or the age of the child. And these rates have more than tripled since 1967. (see Figure 5) In 2010, 36.5 percent of working mothers between the ages of 30 to 44 were breadwinners for their families, compared to 30.2 percent in 2007 and only 10 percent in 1967. Younger working moms saw a similar increase in 2010 (32.1 percent) compared to 27.4 percent in 2007 and 8.4 percent in 1967.

The same pattern holds true regardless of the child’s age. More than a third of all working mothers of minor children are breadwinners, whether their child is under 18 (35 percent) or under 6 (35.4 percent). The increases have been consistent since 2007, when 30 percent of all working mothers were breadwinners, as were 29.7 percent of working mothers with a child under 6. Again, this is a drastic increase from 1967, when the rates were 11.5 percent and 9.3 percent, respectively.

Conclusion

In 2010 there were more female breadwinners in the United States than in any year since data began being collected. This is partially due to women’s record rate of employment, men’s continued high rates of unemployment, and men’s declining wages. And yet, in spite of women’s ever-growing economic contributions to their families, the gender wage gap persists and the only indications that it is beginning to narrow are due to men experiencing a greater decline in real earnings compared to women.

Closing the wage gap because everyone is doing worse is hardly the same as gender equality. As these numbers make clear, supporting real pay equity for women is important for women and their families.

Sarah Jane Glynn is a Policy Analyst with the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress.

Download this issue brief (pdf)

Read this issue brief in your web browser (Scribd)

See also: