This issue brief contains a correction.

When the U.S. National Park Service celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2016, no mountain peaks will be renamed for railroad mogul Louis W. Hill, no statues will be unveiled for E. H. Harriman of the Southern Pacific Railroad, and no plaques will be dedicated to Southern California auto clubs. In the official histories of the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the heroes of American conservation are named Roosevelt, Mather, Pinchot, Murie, and Carson.

But fewer entities have played a bigger role in protecting the nation’s parks, forests, and coastlines than American businesses. Alongside altruistic environmental values, the promise of profit has powered the movement to preserve the nation’s natural wonders. Industries that sold leisure and travel were instrumental in winning early protections for parks and wilderness areas despite the protestations of timber barons, mining magnates, and private developers. Hill’s Great Northern Railway, for example, lobbied for the creation of Glacier National Park.* Harriman’s Southern Pacific Railroad stepped in to support the establishment of Yosemite National Park. And Southern California’s auto clubs joined the American Automobile Association, or AAA, to shape the National Park Service in its early years.

The business of the outdoors

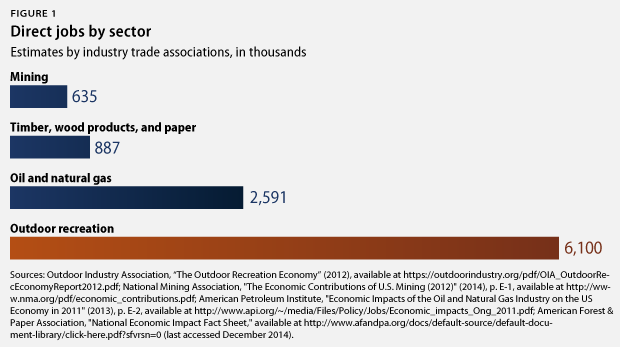

The economic arguments for protecting public lands and waters are so deeply rooted in history and society that they are second nature to most Americans today. Public opinion research commissioned by The Colorado College in 2013 found that more than 9 in 10 Westerners see national parks, national forests, wildlife refuges, and other public lands as essential to the economic prosperity of their state. A growing body of research shows that proximity to parks, trails, and outdoor spaces is among the most prominent factors that businesses and workers consider when choosing where to locate. Consumers are bombarded with ads from health insurance companies that encourage them to get outdoors to improve their health and to cut medical costs. The evolving uses of the outdoors have even affected American fashion, with outdoor gear now so ubiquitous that companies such as The North Face and Patagonia have become global brands. Indeed, the outdoor recreation industry currently supports 6.1 million jobs in the United States. According to reports commissioned and published by the industries themselves, U.S. outdoor recreation accounts for more direct jobs than oil, natural gas, and mining combined. (see Figure 1)

A powerful sector with unmeasured potential

At a broad level, the outdoor economy can be defined as the stream of economic output that results from the protection and sustainable use of America’s lands and waters when they are preserved in a largely undeveloped state. Although the jobs and value associated with protected lands, clean rivers, and healthy oceans have become a cornerstone of the American economy over the past century, the U.S. government does not measure or track these outputs as it does the outputs of other economic sectors. In what are known as “national economic accounts,” reported by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, or BEA, the government measures trends within the energy, health care, and education sectors. But it is currently unable to estimate the contributions of outdoor recreation to the nation’s gross domestic product, or GDP, let alone describe the value of the quality-of-life, health, and other benefits attributable to the American outdoors.

Measuring the outdoor recreation economy is not a simple task, but there are a growing number of reliable tools that help estimate the economic benefits of healthy lands and waters. In fact, the idea of integrating environmental value into national economic accounts is not only supported by institutions such as the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, but it is also important enough that these groups have developed best practices for measuring the benefits.

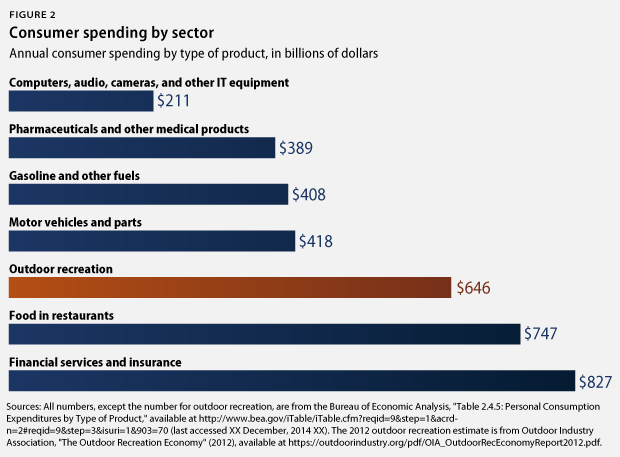

Calculating much of the economic activity attributable to the outdoor economy is relatively straightforward. By using the existing data currently fragmented in the national economic accounts, economists are able to aggregate consumer spending on outdoor gear, equipment, travel, hotels, and other expenses related to tourism and use of the outdoors. (see Figure 2) The Outdoor Industry Association—a trade group that represents manufacturers of outdoor gear and associated suppliers, distributors, and retailers—has estimated that American consumers spend $646 billion each year on outdoor recreation. The U.S. Travel Association, an organization that represents the U.S. travel and tourism industry, estimates that leisure travel in and to the United States generates $621 billion in direct spending each year.

Of course, the outdoor economy encompasses not only the spending and jobs that result from tourism and outdoor recreation, but also the quality-of-life benefits that attract workers and businesses to communities with outdoor amenities, the health benefits associated with outdoor activities, and a range of other outputs.

Measuring some of these other economic benefits—including the overall value of healthy, protected lands and waters—requires more-advanced techniques. Economists, for example, have long been equipped to calculate the economic value of a forest if all its timber is cut and sold. In recent years, however, they have also developed increasingly sophisticated methods of calculating the economic value of that forest if, instead of being logged for timber, the land is conserved for other needs such as recreation opportunities, clean water, and wildlife habitat. In some cases, economists are able to estimate the dollar value of these benefits by comparing the land values of similar properties that do and do not have access to outdoor recreation opportunities. The difference in value—properly measured—can be attributed to the benefits of access. This type of research, conducted through a variety of methodologies, is now sufficiently mature to inform nationwide natural resources management decisions and policies.

Learning from state efforts

Although the federal government has been slow to measure and account for the economic value of protected lands and waters, states are breaking new ground with their economic research on the outdoor economy. For example, California measures both the economic impact of outdoor recreation across the state and the economic contribution of the state park system. A 2011 state study notes that quality-of-life benefits associated with recreational opportunities and infrastructure—in terms of keeping people healthy, attracting workers, and attracting employers—could be a state economic contributor that is at least as important as the direct sale of outdoor products and services. California, Oregon, and New Hampshire are among a growing number of states employing visitor-use surveys and economic benefit analysis to help guide their conservation and recreation investments and plans.

Economists have also developed a growing body of research on the relationship between communities’ economic growth and their proximity to open spaces. A 2012 Headwaters Economics study found that areas in the West with protected public lands have higher rates of job growth and that proximity to the protected land is “correlated with higher levels of per capita income.” According to economist Ray Rasker, the study’s lead author, areas with national parks, wilderness, and other recreational assets are succeeding in attracting high-wage, high-skill jobs more rapidly than similar communities without such amenities. “Communities with protected public lands have a competitive advantage in attracting the engineers, architects, software developers, doctors, lawyers, researchers, and others,” Rasker recently wrote in the Missoulian.

Individuals who live in these communities and those who take advantage of recreational opportunities enjoy health and other social benefits that increase their overall quality of life. Over the past few decades, researchers have studied the strong link between outdoor recreation and improved physical and mental health. Among older populations and children, for example, research has shown that increased access to nature and outdoor spaces reduces stress levels. Studies have also found correlations between an individual’s proximity to public lands or open spaces and better employment opportunities, higher-quality schools, reduced crime rates, more social services, and higher property values.

Measure outdoor recreation’s contributions to the U.S. economy

Even though individual states and trade groups have successfully measured components of the outdoor economy—especially the value of outdoor recreation—these estimates are in no way a substitute for a comprehensive, national assessment of the outdoor economy’s employment and gross domestic product contributions conducted by independent economic experts. Former President Bill Clinton recognized this need in 1993 with an Earth Day commitment to prioritize the development of so-called green GDP measures that “would incorporate changes in the natural environment into the calculations of national income and wealth.” Following this commitment, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reportedly accelerated its work to measure the value and economic contributions of the nation’s natural resources, but Congress ordered the effort suspended in 1994. More than two decades after President Clinton’s commitment, it is time for the U.S. government to resume the project of collecting and publishing information on the economic value of America’s great outdoors—just as it does for every other major sector of the economy.

The Obama administration can take a first step toward accounting for the value of the outdoor economy by directing the BEA—with support from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Bureau of the Census, and U.S. natural resource agencies—to immediately begin reporting on the jobs and economic benefits associated with outdoor recreation in the United States.

This project could be modeled on a similar effort BEA recently undertook in conjunction with the National Endowment for the Arts to better account for the value of arts and culture in the U.S. economy.The BEA has ample information at its disposal to begin calculating the extent of the jobs and economic benefits associated with outdoor recreation, such as data on the employment and economic contributions of travel and tourism, the manufacture and sale of gear and apparel, and even individual outdoor activities such as fishing and hunting. Other agencies within the federal government also have relevant data to offer, such as the U.S. Department of the Interior’s research on the economic impacts that national parks have on their surrounding communities and the U.S. Forest Service’s analysis of the economic value of recreation on its lands.

The U.S. government should supplement this existing information by collecting new data. For example, to better understand the extent to which international tourists use outdoor amenities, the U.S. Department of Commerce should update its questionnaire for departing travelers to ask for more detailed information about the amount of time and money spent visiting national parks or other public lands. To better understand the value that outdoor recreation opportunities can bring to residents’ quality of life, census surveys should include questions on why Americans choose to live where they do and how Americans measure the benefits of nearby outdoor spaces. Federal natural resource agencies, for their part, should begin to collect better information on visitation to public lands and the types of activities that draw Americans outdoors.

Conclusion

Having basic information about an economic sector—such as the number of people it employs and how much economic value it produces—is indispensable to the development of effective, economically efficient policies that promote and sustain economic growth and stability. “In a complex and wealthy country like the United States, providing information on the structure and interactions of the economy and the environment is an essential function of government,” wrote economist William D. Nordhaus in 1999, when he chaired a panel of distinguished economists tasked with making recommendations on how best to integrate national and environmental accounts. Imagine creating a national transportation policy without data on how Americans rely on transportation or instituting a national energy policy without data on the economic benefits and costs of various energy supplies. Policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels are making decisions that affect the landscapes and waters that underpin America’s vibrant outdoor economy without basic data on the sector’s economic contributions.

With the centennial of America’s National Park Service approaching in 2016, now is the moment for the Obama administration to address this lack of information. By recognizing outdoor recreation as a crucial economic sector—and measuring it as such—the administration can lay the groundwork for more economically efficient resource decisions; policies that encourage the growth of outdoor-related businesses; and ultimately, more, better, and higher-paying jobs.

Matt Lee-Ashley is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Public Lands Project at the Center for American Progress. Claire Moser is a Research and Advocacy Associate at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center.

*Correction, January 23, 2015: This issue brief has been corrected to reflect that Louis W. Hill’s Great Northern Railway lobbied for the creation of Glacier National Park.