See also: Making Our Middle Class Stronger by David Madland; The Middle Class and Economic Growth by Michael Ettlinger; Video: Once Upon a Trickle Down: The Rise and Fall of Supply-Side Economics by the Center for American Progress and Mark Fiore

Download this issue brief (pdf)

Read this issue brief in your web browser (Scribd)

Infographic: Seven Graphs That Show Supply-Side Doesn’t Work

Adherents of the economic theory known as supply-side economics contend that by cutting taxes on the rich we will unleash an avalanche of new investment that will spur economic growth, and boost job creation, leading to economic improvements for everyone. For most of the past 30 years this idea has dominated the economic debate, resulting in two sustained eras of tax cuts aimed at the wealthy, separated by a brief respite in the 1990s.

Now, as our economy struggles to emerge from the deepest recession in generations—and as we argue over what to do with the expiring Bush-era tax cuts—it is more important than ever to understand one simple fact: When put to the test in the real world, supply-side policies did not deliver as promised. In fact, by every important measure, our nation’s economic performance after the tax increases of 1993 significantly outpaced that of the periods following the tax cuts of the early 1980s and the early 2000s.

Supply-side economics starts from the generally accepted economic insight that tax policy can influence private-sector decisions by changing the incentives to work and invest. But supply-side acolytes take this relatively mundane observation to an extreme conclusion. They argue that lowering taxes for people, especially for those who have a lot of money to invest, will always lead to better economic results, and furthermore, that lower taxes is the single most critical intervention the government can undertake to stimulate growth.

This assertion—that lower taxes for the rich will lead to improved economic results—is testable. Of course, pure natural experiments in economics are few and far between, but over the last 30 years the United States alternated between economic policies that were heavily influenced by supply-side ideas, then were not, then were again. This variation allows us to compare economic performance in the various eras. If proponents of supply-side theory are correct, then the supply-side eras should outperform the non-supply side era. But that’s not what happened.

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan signed a large tax cut package into law, which lowered the top income tax rate by 20 percentage points and cut taxes for the rich and for corporations. The next several years saw numerous additional tax legislations passed, much of which represented retreats from supply-side ideology. Nevertheless, this supply-side era continued into the 1990s. In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed a major tax increase into law. That legislation raised the top marginal income tax rate paid by the wealthy, and also extended Medicare taxes to higher income individuals. And despite the capital gains tax cut of 1997, the 1990s represented an eight-year respite from supply-side policies.

Those policies returned in force in 2001 with the enactment of tax cuts by President George W. Bush. To this day, we are still living, by and large, with the tax code from the Bush era—with the only differences being further tax cuts signed by President Barack Obama.

In order to evaluate whether supply-side policies really delivered on their promise, we looked at the economic performance of the three eras, all beginning at equivalent points in the business cycle. Since the 1993 tax increases were passed 10 quarters into an economic expansion, we compared performance for all three eras starting 10 quarters into their respective expansions, and then going forward five years from that point, or—in the case of the 2000s—until the expansion ended in December of 2007.

We compared performance during these equivalent years along seven key economic measures. Here are the facts.

Investment growth was weaker under supply-side policies

The critical link in supply-side theory’s chain is business investment. Proponents argue that lower taxes on the rich will spur more investment, and since investment is a key ingredient to growth, that will boost the overall economy. But investment growth during both supply-side eras lagged far behind that of the 1990s when taxes were higher. (see Figure 1)

Productivity growth was weaker under supply-side policies

A second key ingredient in the supply-side recipe is increasing worker productivity. The theory says that more business investment will result in innovations that allow each worker to produce more, thus growing the pie for everyone. But as with investment growth, productivity growth under supply-side policies fails to impress when compared to the higher tax era. (see Figure 2)

Overall economic growth was weaker under supply-side policies

With their lackluster investment and productivity growth, it’s not surprising that overall economic growth during the supply-side eras also lagged behind the higher-tax era. The expansion following the Bush tax cuts was especially weak. (see Figure 3)

Employment growth was weaker under supply-side policies

Because the higher-tax period experienced faster growth, it also enjoyed a booming job market. Employment growth after the 1993 tax increases outpaced that of both the 1980s supply-side period and the 2000s supply-side period. Again, the most recent supply-side period was especially bad for employment growth, averaging just 1.5 percent increases a year. (see Figure 4)

Income growth for middle-class households was lackluster under supply-side policies

Supply-side theory posits that when the tax burden on the rich is reduced, it will eventually help everyone. And conversely, if you raise taxes on the rich, then everyone will end up paying the price. Of course, if that were the case, we should have seen robust income growth for middle-class families under supply-side policies and stagnation under the higher-tax regime. But we saw just the opposite. After the tax increases, income for the median household grew at nearly twice the rate as it did under the supply-side tax policies. (see Figure 5)

Hourly earnings were flat or declined under supply-side policies

One of the ways that lower taxes on the rich is supposed to end up helping the middle class is by resulting in higher hourly earnings. Why? Because if investment leads to boosted productivity, then that boosted productivity should be reflected in wages. Is that what happened? No. We didn’t get the investment boost, or the productivity boost, and we certainly didn’t get the wage boost in either supply-side era. In fact, hourly earnings (after accounting for inflation) fell during the 1980s, and were flat during the one in the 2000s. But during the 1990s, after the tax hikes, real hourly wages grew by about 1 percent a year. (see Figure 6)

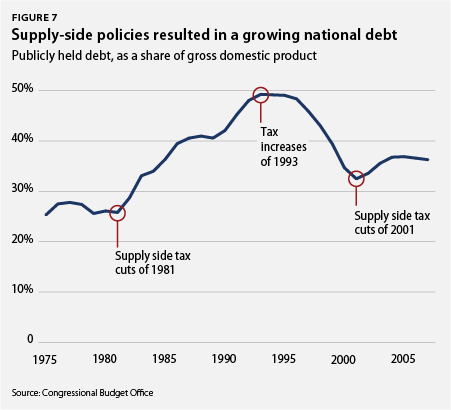

Our nation’s fiscal health deteriorated under supply-side policies

Some of the more dedicated supply-side devotees go so far as to argue that tax cuts for the rich will result in so much additional economic activity that they will actually increase government revenues, thereby “paying for themselves,” and have no negative impact on the bottom line. This assertion, as with the others, is not supported in the data. Not only did government revenues fall during the supply-side era, but the bottom line deteriorated noticeably, too. Publicly held debt rose during both supply-side eras, and fell substantially during the higher-tax period. (see Figure 7)

Conclusion

Did the supply side policies of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush work? Did they boost investment, spur growth, and cause prosperity to trickle down? The data says no. And when President Clinton raised taxes in 1993, did the economy suffer a slowdown, as was predicted by those who believe in supply-side economics? Again, the data says no.

This data does not mean that higher taxes are always better and lower taxes are always worse for the economy. That would be making the same mistake that many supply-siders make, but in reverse. Indeed, there were obviously other forces at work in our economy besides tax policies over this 30-year period. But it does mean that lower taxes aren’t always the answer, aren’t a magical economic cure, and that higher taxes can coexist with, and perhaps even aid, a strong economy.

Michael Ettlinger is Vice President for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Linden is Director of Tax and Budget Policy at the Center.

Note: This analysis was based on a earlier report jointly issued by the Center for American Progress and the Economic Policy Institute, entitled, “Take a Walk on the Supply Side,” authored by Michael Ettlinger and John Irons. The numbers in this brief have been updated with the latest data, and thus differ slightly from that original paper. For more information on methodology and a deeper discussion of supply-side theory, please refer to the original publication.

Download this issue brief (pdf)

Read this issue brief in your web browser (Scribd)

See also: