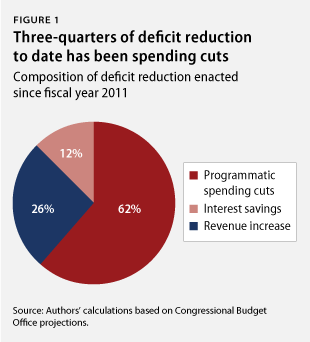

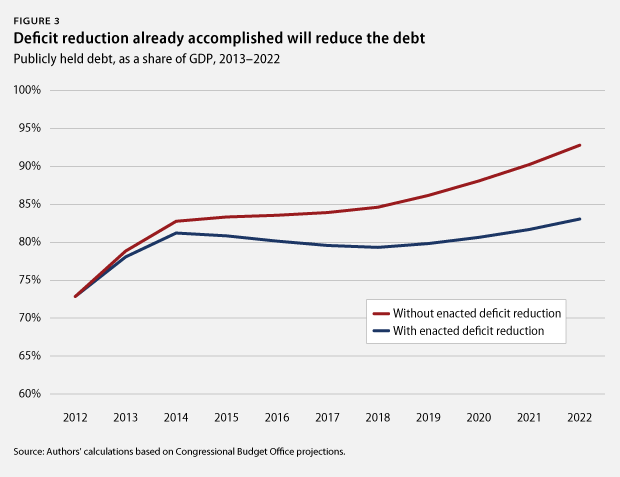

Since the start of fiscal year 2011, President Barack Obama has signed into law approximately $2.4 trillion of deficit reduction for the years 2013 through 2022. Nearly three-quarters of that deficit reduction is in the form of spending cuts, while the remaining one-quarter comes from revenue increases. (see Figure 1) As a result of that deficit reduction, the projected rise in debt levels from today through 2022 has decreased by nearly 10 full percentage points of gross domestic product. In fact, under today’s policies, debt levels in 2022—as a share of GDP—will be only slightly higher than they are expected to be by the end of next year. That doesn’t mean there is no more work to be done, but it does show we’ve come a long way already.

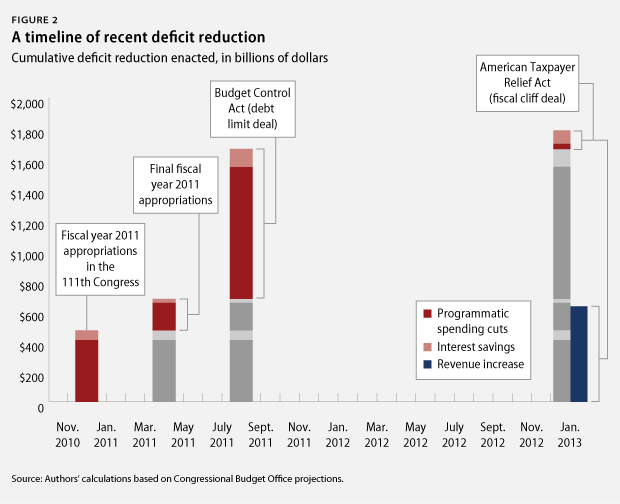

Congress has enacted several major pieces of legislation since the start of the 2011 fiscal year that will reduce future budget deficits relative to what they would have been had we continued forward under the policies in place before the enactment of those bills. The first of these deficit-reducing bills were the continuing resolutions passed between September 30 and December 21, 2010. Those bills provided temporary funding for a wide swath of government services and programs, but they did so at a lower level than funding had been for the previous year, after adjusting for inflation. Because the Congressional Budget Office assumes that this type of spending—known as discretionary spending—will increase each year with inflation, those first temporary appropriations bills in 2011 cut the Congressional Budget Office’s projection of discretionary spending from 2013 through 2022 by more than $400 billion.

The last temporary appropriations bill passed in December 2010 ran out on March 4, 2011. The new Congress then enacted several more temporary bills, and finally, on April 15, 2011, passed a full appropriations bill for the remainder of the 2011 fiscal year. This second half of the appropriations process also cut a substantial amount of spending. Each new appropriations bill passed by the new Congress cut funding even more than the first set had. The result was another approximately $180 billion in spending reductions over the 10-year period. Altogether, the fiscal year 2011 appropriations process reduced future discretionary spending by $585 billion, or about 4.3 percent.

Over the subsequent several months, Congress engaged in a protracted debate over the looming debt limit. The result of that debate was a bill titled the Budget Control Act. The act—also known as the debt-limit deal—reduced spending again. It did so mainly by setting caps on the overall amount of discretionary resources that Congress could allocate each year for the next decade. These caps were set even lower than the just-enacted, inflation-adjusted 2011 levels. So after already cutting spending several times to the tune of more than $500 billion, the Budget Control Act cut spending again—this time by approximately $860 billion. Together, the fiscal year 2011 appropriations process and the Budget Control Act are responsible for nearly $1.5 trillion in discretionary spending cuts. This is a whopping 10.6 percent reduction from inflation-adjusted 2010 spending levels.

All these direct programmatic spending cuts also have a secondary spending effect on the budget deficit. Reducing the deficit—either through spending cuts or revenue increases—allows the federal government to incur less debt, which in turn means that there will be less interest to pay back to lenders. In this case, that $1.5 trillion in spending cuts will also result in about $200 billion in reduced spending on interest payments.

In addition to the discretionary spending caps, the Budget Control Act set up a second process whereby a special congressional committee, known as the “super committee,” was tasked with finding an additional $1.2 trillion to $1.5 trillion in deficit reduction. If this “super committee” failed—which it ultimately did—a set of deliberately draconian spending cuts totaling approximately $1.2 trillion would be automatically triggered. Known as the “sequester,” those cuts were intended to be so damaging that Congress would work together to find a better way to reduce the deficit. Because Congress didn’t do that, however, the sequester was triggered and was set to kick in at the beginning of 2013.

The beginning of 2013 also happened to be the deadline for dealing with the expiring Bush tax cuts, as well as a number of other expiring tax and spending provisions. The combination of all these fiscal deadlines became known as the “fiscal cliff.” And the resolution of the fiscal cliff resulted in yet more deficit reduction.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act—the bill passed by Congress and signed by the president to avoid much of the fiscal cliff—extended most of the Bush tax cuts but allowed those that affected only households with incomes of more than $450,000 to expire, resulting in a 10-year revenue increase of a little more than $600 billion.

The bill also included a number of other deficit-reducing measures. It paid, with offsetting spending reductions, for a one-year patch of the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate—a formula that, if left unfixed, results in very large cuts to Medicare doctors’ pay. Since most projections of the future budget deficit assume that Congress will continue to patch the Sustainable Growth Rate without paying for it, the American Taxpayer Relief Act reduces those future deficits by actually offsetting the cost this time.

Similarly, the fiscal cliff deal temporarily postponed the sequester, paying for it with offsetting spending cuts and revenue increases. As with the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate, projections of future deficits assume that the sequester will not go into effect. Postponing the sequester without paying for it, therefore, wouldn’t increase the future deficit since projections already assume Congress will postpone it. But by paying for the delay, the future deficit actually becomes smaller than we expected.

Several questions remain regarding the rest of the sequester, however: Will it eventually go into effect? If not, will its repeal be paid for? If so, how will it be paid for? These questions will determine if even more deficit reduction ultimately comes out of the Budget Control Act and the American Taxpayer Relief Act. Since those questions are as yet unanswered, the effects of the remaining sequester are not included in this analysis.

Altogether, the American Taxpayer Relief Act will reduce deficits over the next 10 years by about $750 billion. Of that deficit reduction, approximately $630 billion comes from revenue increases, approximately $30 billion comes from programmatic spending cuts, and the rest comes from interest savings resulting from lower deficits. (see Figure 3)

So where does all this deficit reduction leave us? Since the start of fiscal year 2011, Congress and the president have cut about $1.5 trillion in programmatic spending, raised about $630 billion in new revenue, and generated about $300 billion in interest savings, for a combined total of more than $2.4 trillion in deficit reduction. The result is a substantial cut in how much publicly held debt the country is expected to hold 10 years from now. Instead of reaching nearly 93 percent of GDP, debt is now projected to total about 83 percent of GDP—fully 10 points lower. And while that won’t be enough to finally put the budget onto sustainable footing, it is a massive improvement. In fact, it’s about two-thirds of the way toward stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio.

It’s been a bumpy few fiscal years. But don’t let all the twists and turns obscure the simple fact that we actually have accomplished a significant amount of deficit reduction along the way. Three-quarters of that deficit reduction has been achieved through spending cuts totaling $1.8 trillion, with only one-quarter coming from revenue increases.

Michael Linden is the Director for Tax and Budget Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Ettlinger is the Vice President for Economic Policy at the Center.