Budgets are about choices. The budget agreement announced by Senate Budget Committee Chairwoman Patty Murray (D-WA) and House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI) makes plenty of choices—many of them good, others less so—but the sum total of their choices results in a package that moves the country in a positive direction. The Murray-Ryan deal would, for the time being, put the seemingly constant fiscal crises to rest and roll back some of the damaging austerity spending cuts that have been undermining the economic recovery.

Of course the deal could have made better choices. Conservatives’ refusal to consider any measures that could be considered tax increases took many good policy options off the table, such as closing loopholes exploited by Wall Street and big corporations. The Murray-Ryan deal does include some new revenue from other sources, such as user fees, but these fee increases require more sacrifice from the middle class than would have been necessary if conservatives had been willing to consider closing tax loopholes instead.

But in a world where the Tea Party openly claims that sequestration—a policy that the Congressional Budget Office says will cost us 800,000 jobs this year—is a “victory,” this deal is a relative success. Some unhappy compromises had to be struck to make it happen, but the Murray-Ryan deal is certainly a better choice than further damaging our economy with another full year of sequestration.

Reversing course on austerity

Reducing the sequester is a big victory for the American people, as it partially removes a major roadblock to rebuilding our economy. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that 750,000 more jobs would have been created or retained in 2013 if not for the sequester. The sequester has already thrown 57,000 kids out of Head Start preschool programs, held back scientific research, and undermined federal law enforcement.

Another year of sequestration would be much worse. The cuts are larger, and federal agencies are running out of one-time fixes to mitigate the damage, meaning sharper cuts to economic investments, public safety, and safety net programs. For example, while the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI, was able to use budget gimmicks to avoid furloughs under the first year of sequestration, next year’s sequester would close FBI offices and furlough agents for approximately 10 days.

Although the sequester should be eliminated completely, a partial reduction is still a positive step toward reversing the damaging austerity of the past several years. Congress has repeatedly slashed spending since 2011; sequestration is only the most recent example. A Macroeconomic Advisers report estimates that austerity has eliminated 1.2 million jobs so far.

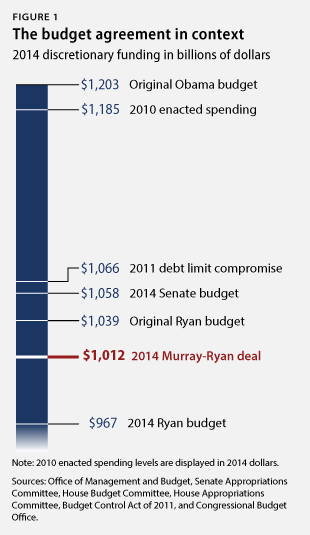

The partial sequester repeal in the Murray-Ryan deal is a bipartisan acknowledgement that austerity has gone too far. The budget deal sets an overall base discretionary spending limit of about $1.012 trillion for fiscal year 2014, which is $45 billion more than the 2014 sequestration-mandated spending cap of $967 billion. But the FY 2014 spending limit in the Murray-Ryan deal is still $54 billion less than the original pre-sequester limit of $1.066 trillion agreed to in the Budget Control Act of 2011, which had already been slightly reduced to $1.058 trillion by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. The Murray-Ryan deal represents an even larger cut of $173 billion from the inflation-adjusted spending levels in FY 2010. It will be up to Congress to allocate this limited funding to mitigate the worst impacts of sequestration, which is an opportunity to reverse some of the most devastating cuts to sectors such as education, research, national security, infrastructure, public safety, and the social safety net.

Difficult choices

Although reversing course on sequestration is an important step toward sensible fiscal policy, it does not come without a price. To win conservative support, the Murray-Ryan deal unfortunately has to include policies that are not nearly as attractive as alternatives that never got a fair hearing. Specifically, by all accounts, Rep. Ryan would not consider tax changes that raised new revenue, no matter how smart, fair, or efficient those changes would have been.

Taking tax loopholes off the table forced Sen. Murray and Rep. Ryan to make worse choices than they would have otherwise. For example, the budget deal includes an increase in fees charged to airlines for aviation security. Airlines warn that the higher fees will make flying more expensive for customers. On the other hand, the higher fees will more accurately reflect the government’s costs for protecting the airlines. President Barack Obama also proposed increasing these fees in his budget.

Raising aviation-security fees is a reasonable step, but a better choice would have been closing a tax loophole for private jet owners. Currently, the cost of buying a private jet for business purposes is deducted from the owner’s taxable income over five years, even though commercial aircraft are deducted over a longer seven-year period. This special treatment for private jet owners costs taxpayers about $3 billion over 10 years. That money could have been used to ease the increase in aviation security fees.

The Murray-Ryan agreement also brings in additional revenue by raising the fees charged to companies offering pensions to their workers, which pay to federally insure those pensions with the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, or PBGC. While President Obama included similar proposals in his most recent budget, this is far from the best option available to bring in new revenue. Companies are still adjusting to an earlier increase in PBGC fees, and higher fees could discourage companies from offering their workers the retirement security of a defined-benefit pension.

Instead of making it harder for middle-class workers to save for their retirement, Congress could have closed a loophole that extremely wealthy investment-fund managers exploit to pay lower taxes than other workers. Fund managers are often paid based on the performance of their investments, which takes the form of a “carried interest” for the fund manager. Even though the manager does not invest his or her own money in this carried interest, the income from it is still taxed at the preferential low rates otherwise reserved for investment income. Taxing carried interest income using the same rates that other workers pay on their income would raise about $16 billion over 10 years.

The deal could have also included better choices when it comes to spending cuts. The budget agreement cuts military retirement benefits and increases the payroll deduction that federal civilian workers pay for their retirement plans. Instead, the deal could have chosen to crack down on “pay-for-delay” agreements, in which brand-name prescription drug companies pay manufacturers of generic drugs to keep the cheaper generic alternative off the market. This collusion drives up health care costs for the government and private consumers. President Obama’s budget and bipartisan Senate legislation would restrict this anti-competitive practice. If the Murray-Ryan deal included this provision, it would cut spending in government health programs by an estimated $11 billion over 10 years—nearly enough to replace the cuts to military and civilian federal retirement benefits.

On the other hand, the Murray-Ryan deal also makes several excellent choices. Under the agreement, the government will not reimburse contractors for salaries of more than $487,000, which means taxpayers will not foot the bill for excessive executive compensation of government contractors. The deal also makes no cuts to Social Security and no cuts to Medicare or Medicaid benefits.

Conclusion

For the past several years, Congress has repeatedly chosen austerity over growth. A perfect budget agreement would recognize that austerity has failed our economy, repeal sequestration completely, and make new investments in the middle class to grow our economy. As President Obama recently said, “A relentlessly growing deficit of opportunity is a bigger threat to our future than our rapidly shrinking fiscal deficit.”

The Murray-Ryan budget agreement is far from perfect. It only partially repeals the damaging austerity of sequestration. It makes some unfortunate but inevitable choices about where to cut spending and raise revenue, choices owed to conservative refusal to close any tax loopholes.

But for all of the suboptimal choices in the Murray-Ryan deal, it is still a step in the right direction. Reducing the sequester means more economic investment, increased public safety, and a stronger social safety net. The dealmakers made the right choice to split sequester relief evenly between defense and nondefense programs. And after years of governing by crisis, this budget deal means we can put the constant and divisive debates about the federal budget to the side for the immediate future. If that allows Congress the time and space to seriously address our other pressing needs—such as creating jobs, strengthening the middle class, and reforming our broken immigration system—then that alone will have made it a good deal.

Harry Stein is the Associate Director for Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Linden is the Managing Director for Economic Policy at the Center.