Despite years of progress in addressing sources of pollution, air quality in the United States appears to be declining as increasingly more Americans live in counties experiencing unhealthy spikes in air pollution. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) current review of the national ambient air quality standards (NAAQS) provides an opportunity for the agency to institute stricter standards to build on the Biden administration’s landmark climate, jobs, justice, and clean energy investments. Stronger standards would help address the historical injustices of pollution from the fossil fuel industry harming environmental justice communities.

The Clean Air Act mandates the EPA to improve air quality, including setting NAAQS for six common air pollutants: ground-level ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, lead, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide.

Defining particulate matter and soot

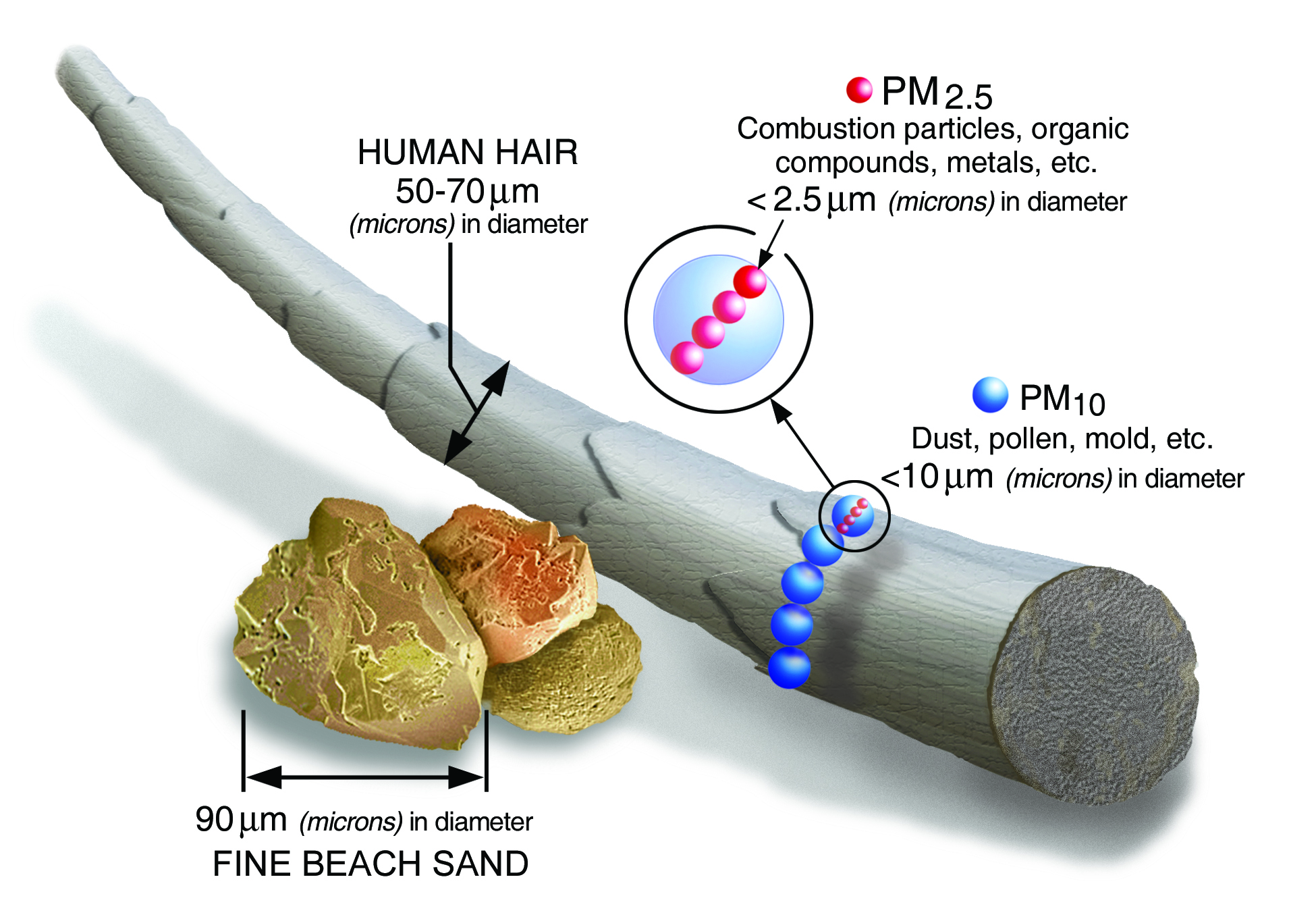

Particulate matter, sometimes referred to as particle pollution, is the mixture of solid and liquid particles found in the air, including dust, soot, dirt, and smoke. Some particles are large enough to be seen by the naked eye and are classified as PM10, while others are smaller than 2.5 micrometers and are classified as PM2.5, or soot. Soot is the deadliest of particle pollutants since its small size allows it to penetrate the lungs and bloodstream.

Soot is produced in a variety of ways, with some being emitted directly from the source, including construction sites, fires, or unpaved roads. However, the majority of soot is the result of chemical reactions that occur in the atmosphere from burning coal for electricity or from industrial fuel, motor vehicles, or oil refining.

This image illustrates the sizes of different kinds of particulate matter. The illustration is courtesy of the Environmental Protection Agency.

The standards around particulate matter are in urgent need of an update. The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to review and appropriately revise NAAQS for particulate matter every five years, based on the latest science, for the benefit of public health and the environment. In 2020, a committee of independent advisers to the EPA “unequivocally and unanimously” concluded that the existing soot standard did “not adequately protect public health” and recommended it be strengthened. Yet the Trump administration released a final decision retaining the outdated and inadequate soot standards—against the findings from the administration’s own scientists and pleas from public health experts and environmental justice organizations. On January 20, 2021, the Biden administration issued an executive order directing the EPA to reevaluate the 2020 decision based on available scientific evidence that current particulate matter standards are inadequate for protecting public health and welfare.

This column discusses the health and environmental justice ramifications of unrestricted soot pollution and recommends that the EPA implement strong, scientist-proposed air quality standards that protect both human and planetary health.

Soot is linked to hospitalization, serious health complications, and premature death

Particulates, especially those that are small enough to be inhaled, such as soot, can cause serious health issues and exact a costly toll on public health. These harmful impacts are well documented: Soot pollution has been linked to hospitalization and emergency department visits; serious health conditions, including asthma, brain damage, heart attacks, Parkinson’s disease, and lung disease; and both adult and infant mortality. Since 2012, when the EPA set the current NAAQS at an annual average of 12 micrograms per cubic meter and a 24-hour average of 35 micrograms per cubic meter, studies have shown that exposure even at these levels causes tens of thousands of premature deaths in the United States every year. In fact, soot is the air pollutant most directly linked to premature mortality. Experts estimate that every year, soot is responsible for 85,000 to 200,000 excess deaths in the United States.

Further reducing air pollutants, including soot, beyond current standards would therefore have a significant impact on public health. In fact, the benefits of lowering soot concentrations in the air could be considerable: One study indicated that lowering the air pollutant concentration from the 70th percentile to the 60th percentile would prevent approximately 65,935 premature deaths among older adults per year. At current levels, experts say, the risk of premature death is “unacceptably high.”

Listen to a story that illustrates the importance of environmental standards such as NAAQS

Differences in soot exposure deepen racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic health disparities

A 2022 report by the American Lung Association (ALA) found that 63 million Americans live in counties that experience unhealthy daily spikes in soot pollution, and 21 million live in counties that exceed annual limits for soot pollution. According to the ALA’s report, nearly 90 percent of the counties that received failing grades for spikes in soot were in 11 Western states—a marked shift from 2007, during which approximately only 23 percent of the counties with failing grades were in the West. The report also found that people of color were 61 percent more likely than white people to live in a county with unhealthy air quality.

Many Americans live in areas with unhealthy air quality—and the costs of pollution are high

63M

Number of Americans who live in counties that experience unhealthy daily spikes in soot pollution

21M

Number of Americans who live in counties that exceed annual limits for soot pollution

85K–200K

Number of excess deaths in America caused by soot pollution each year

A history of environmental racism and racial segregation has left a disproportionate number of Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities exposed to soot and its impacts on health. Over the years, practices such as redlining have meant that people of color live in neighborhoods with more smog and soot from vehicles, coal plants, and other industrial facilities. A 2021 study conducted by the EPA-funded Center for Air, Climate, and Energy Solutions found that people of color are exposed to more soot than their white counterparts, regardless of location or income level. This study is one of many that have found strong evidence for racial and ethnic and socioeconomic differences in soot exposure and health risks. As a result, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black populations are at greater risk of experiencing worse health outcomes, including cause-specific mortality and incident hypertension, compared with white populations.

In addition to facing greater exposure to soot, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black populations are at greater risk of experiencing soot-related health impacts based on preexisting conditions not related to air pollution. Studies have found that individuals with existing cardiovascular or respiratory disease, populations who are overweight/obese, and populations with particular genetic variants are at an increased risk of soot-related health impacts. Black or African American and American Indian or Alaska Native individuals are more likely than white adults to experience hypertension, strokes, and asthma. As a result, these communities suffer from increased exposure and higher incidences of comorbidities, leaving them doubly vulnerable.

Read more on the social determinants of health and policies to improve health equity

Recommendations to reduce soot pollution

Given the abundance of evidence demonstrating the dangers and health disparities caused by soot pollution, the EPA must follow the guidance from its own Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee and public health experts. As the EPA reconsiders the Trump administration’s decisions to retain outdated standards—a process that is expected to wrap up in March 2023 with the issuance of a final rule—it should strengthen NAAQS soot standards to no higher than the recommended standard of 8 micrograms per cubic meter annually and 25 micrograms per cubic meter daily, compared with the current standard of 12 micrograms and 35 micrograms, respectively.

Tighter federal soot standards are needed to force local authorities to improve air quality in the most-polluted communities. According to the EPA, within one year of revising NAAQS, states and tribes must report to the agency which areas are attaining the standard. Areas that do not attain the standard must develop plans to attain and maintain the stricter benchmarks. Local areas’ and states’ failure to attain and maintain NAAQS standards can trigger federal penalties, including the withholding of federal funds and more stringent permitting requirements. This gives local air pollution control authorities more leverage to oversee stationary sources of air pollution, including factories, refineries, and power plants.

Urgent action is needed in the short term to avoid premature deaths and protect the planet.

Conclusion

Stronger standards would bring the United States into closer alignment with global standards. In 2021, the World Health Organization updated its air quality guidelines for soot to 5 micrograms per cubic meter annually and 15 micrograms per cubic meter daily. While the United States should set itself on a path toward implementing the strongest particulate matter air quality standard possible, urgent action is needed in the short term to avoid premature deaths and protect the planet. The time for inaction has long since passed, and tightening the current standard, even incrementally, will go a long way toward improving air quality, strengthening health, and protecting the most vulnerable communities.