Millennial adults, or Americans between the ages of 18 and 34, are facing greater financial pressures and economic insecurity compared with prior generations.* Millennials with children are especially likely to struggle to make ends meet.

Forty percent of Millennials are already parents, and that percentage is expected to double over the next 10 to 15 years. Children born to Millennial parents make up 80 percent of the 4 million annual births in the United States, and around 9,000 Millennial women give birth every day. Among the older half of the Millennial generation, 10.8 million households already have children.

The Child Tax Credit, or CTC, could play a key role in closing the gap for these young parents. Created to offset the costs of raising children, the CTC currently provides eligible families with up to $1,000 annually for each child under age 17, and it works together with other tax credits to boost economic stability for many low- and moderate-income families with children.

Right now, more than 14 million Millennial parents benefit from the low-income portion of the CTC or the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, or both. But as discussed in further detail in this issue brief, key reforms to the CTC could enable it to better serve the group who needs it most: new Millennial parents.

Economic instability hits Millennial parents hard

As a generation, Millennials were hit hard by the Great Recession—which coincided with the formative years of their careers—so they face huge financial pressures and challenges to their economic stability. Despite the recent decline in the national unemployment rate—which in June hit 5.3 percent, its lowest rate in seven years—unemployment remained above 12 percent among jobless 16- to 24-year-olds searching for work and at 5.6 percent among 25- to 34-year-olds, compared with only 3.7 percent for workers ages 35 and older. In addition to high unemployment among Millennial workers, each new class of college graduates holds record-breaking debt, with the class of 2015 facing an average debt burden of more than $35,000 per borrower. Despite being more educated than past generations, a greater share of Millennials lives in poverty than members of previous generations did at the same age. This includes one-fifth of Millennial parents.

Millennials also have been hit the hardest by stagnant or declining wages: The real median annual income of young people has plummeted over the past 30 years. After adjusting for inflation, the median income of 18- to 34-year-olds is just $33,883 today, compared with $37,355 in 2000, $36,716 in 1990, and $35,845 in the 1980s. This means that members of the Millennial generation are making thousands of dollars less per year in real terms than older generations did when they were between the ages of 18 and 34. What’s more, many Millennials are earning very low wages. In 2014, more than 70 percent of minimum wage earners were between the ages of 16 and 34, yet the federal minimum wage is lower in real terms today than it was in 1968. And many of the workers currently facing these low wages are raising children: According to the Economic Policy Institute, nearly 28 percent of the workers who would be affected by increasing the minimum wage to $12 by 2020 are supporting children under age 18.

It’s exciting to see Millennials—who make up the most diverse generation the United States has ever seen—starting their own families. As new parents know, however, the costs associated with childrearing today are steep. Diapers, to take just one example, average $936 per child each year.

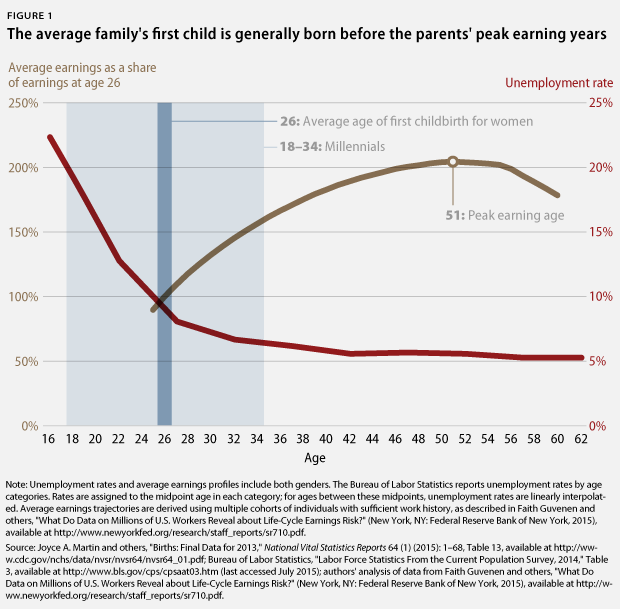

This influx of costs comes well before families’ highest-earning years: As the figure below shows, the typical American worker will not reach peak earning years until about age 51—nearly double the average age of first childbirth for women, which was 26 in 2013. Not only are families formed long before peak earning years, but the typical Millennial family’s first child will be born during a time when the risks of job loss and unemployment remain high because younger workers face greater risk of joblessness than older workers. And many of those without jobs are caring for children: Today, more than 1.4 million caregivers between the ages of 15 and 24 are raising dependent children while out of work and not in school—whether due to job loss, lack of economic opportunity, or barriers to work such as caregiving responsibilities or a disability.

An investment in Millennial parents is an investment in the country’s economic future

The combination of high costs, stagnant or declining wages, and greater financial pressures facing Millennials should be reason enough to strengthen the Child Tax Credit. But in addition to the importance of the CTC for boosting the economic security of low- and moderate-income Millennial families in the short term, tax credits such as the CTC have a huge positive long-term impact on children as well—especially if the credits are delivered during the critical development period when children are very young. Boosting a child’s family income—including through the CTC and the EITC—leads to significantly better health, educational, and employment outcomes later in life. This is particularly the case for poor and low-income children: For each additional $3,000 in annual income that a poor family receives while their child is younger than 6 years old, the child’s annual earnings increase by 17 percent as an adult.

The Child Tax Credit that Millennial families need

The CTC, like other tax credits, works primarily to reduce the amount of federal taxes that a family owes. The CTC is a crucial source of economic stability for families with children. As a first step, lawmakers must make permanent key provisions of the CTC and the Earned Income Tax Credit that will otherwise expire at the end of 2017, driving 16 million people, including nearly 8 million children, into poverty or deeper into poverty. But in addition to making these provisions permanent, a Center for American Progress report outlines several changes that are needed to make the CTC accessible to all low- and moderate-income Millennial parents and to significantly decrease child poverty. These recommendations include:

- Making the CTC fully refundable. Because the CTC is only partially refundable, it does not reach many of the lowest-income children. Full refundability would mean that families who qualify for a credit greater than their total tax liability are refunded for the full remaining portion of their credit. Making the CTC fully refundable would help more low- and moderate-income families better address the costs of raising children.

- Eliminating the minimum earnings requirement. The current CTC also has a minimum earnings requirement of $3,000, which excludes many families whose budgets are the tightest, such as parents who are underemployed or looking for work. Eliminating the minimum earnings requirement would make the CTC accessible to the families who need it the most.

- Indexing the CTC’s value to inflation. The CTC is not tied to inflation, and the value of the credit has already eroded by $340 in real terms since 2001. Indexing the value of the credit to inflation will ensure that the CTC continues to make a meaningful difference for families in the future.

- Creating a supplemental Young Child Tax Credit. The CTC’s modest but important benefit does not increase when families need it most—when children are young. Creating a supplemental Young Child Tax Credit of $125 per month for children under age 3 will further reduce child poverty during this crucial development period, providing critical financial security now and boosting economic outcomes for children later in life.

- Delivering the Young Child Tax Credit on a monthly basis. Right now, families receive the CTC only once per year, at tax time. Delivering the Young Child Tax Credit on a monthly rather than an annual basis would provide greater stability to families with young children and help them meet the continuous costs of childrearing.

Why a stronger Child Tax Credit is key to supporting Millennial families

Millennials are starting families just like previous generations did, but they are raising their children in an environment of much greater economic instability and stress. Millennial parents with young children must face the high and climbing costs of childrearing in addition to the challenges of higher unemployment rates, stagnant wages, and student loan debt—all at the time that is most critical for their children’s development.

Because Millennial parents are more likely to have lower wages and face higher rates of unemployment, their families will disproportionately benefit from making the full CTC available to all low- and moderate-income families. And because Millennial parents are more likely to be raising infants and toddlers, adding a Young Child Tax Credit for children under age 3 would have an especially strong effect in stabilizing these families at a time when it matters most for children’s development.

Strengthening the CTC would make it work more effectively for the families who need it most—when they need it most—to help Millennial families get on their feet as they seek a path to the middle class.

* There is not universal agreement on how to define the Millennial generation, but most sources identify it as those born between about 1980 and about 2000. This brief focuses primarily on Millennial adults but also provides information on younger Millennials where relevant.

Sunny Frothingham is a Policy Advocate for Generation Progress. Rachel West is a Senior Policy Analyst with the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Melissa Boteach is the Vice President of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center. Rebecca Vallas is the Director of Policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program.