The nation’s economy demands that workers possess increasing levels of knowledge, skills, and abilities that are best acquired through postsecondary education. Without workers who have the right foundations, the United States will lose ground to countries that have prepared better for the demands of the 21st century workforce and, ultimately, the United States economy and security will be jeopardized. It is time for a new plan—what CAP calls College for All—to ensure that Americans are prepared to meet the demands of the new global economy.

On January 9, President Barack Obama announced a plan that would go a long way toward making this goal a reality by making community college free for nearly all students. In a recent report, the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity called for taking even more aggressive action to ensure that every American has access to two-year or four-year programs of postsecondary education. Under this College for All proposal, the federal government would ensure that any student attending public college or university would not be asked to pay any tuition and fees during enrollment. Students and families will not need to complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid to receive support from the federal government. Students who achieve significant economic gains from the education they receive would repay some or all of the funds provided through the tax system.

The U.S. economy demands increasing levels of educational attainment

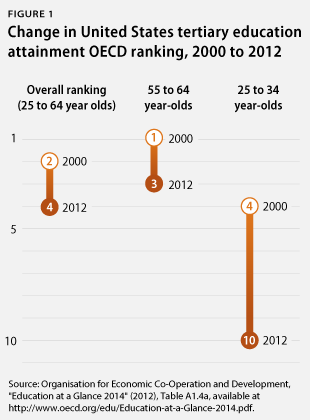

A recent study by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found that at current levels of production, the U.S. economy will have a shortfall of 5 million college-educated workers by 2020. This gap is unsurprising. By 2020, 65 percent of all jobs will require bachelor’s or associate’s degrees or some other education beyond high school, particularly in the fastest growing occupations—science, technology, engineering, mathematics, health care, and community service. Although the U.S. economy is demanding workers with increasing levels of education beyond high school, the postsecondary educational attainment rate has changed very little over the past decade, while other countries have made more significant gains in postsecondary educational attainment. Adults in the United States between the ages of 55 and 64 are the third most educated among the 34 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, countries that are competitors for future jobs. Meanwhile, young adults in the United States ranked 10th in terms of their rate of postsecondary education credentials among OECD peers.

Present-day 55 to 64 year-olds attained postsecondary education at a time when state and federal investment in postsecondary education was high and tuition for public colleges and universities was affordable for many middle-class families. As state investment in postsecondary education has fallen and as tuition and student-loan debt have increased, the current generation has not been able to keep up with the gains in postsecondary educational attainment achieved by many other countries. As older adults exit the workforce through retirement, U.S. economic performance will fall behind societies with higher levels of education.

The federal government has been doing its part by providing tax credits, grants to low- and moderate-income students, and loans to anyone who wants to borrow. In fiscal year 2015, these benefits are estimated to provide a total of more than $160 billion to students enrolled in postsecondary education.

If the federal government is providing this much support, why hasn’t the United States seen dramatic changes in the share of the nation’s adult population with postsecondary degrees and certificates? First, after making considerable gains beginning in the 1970s, the college-going rate among recent high school graduates has flattened, particularly among students from low-income families. As noted in a recent Center for American Progress report, titled “A Great Recession, a Great Retreat,” the country has begun to lose ground on college-attainment rates as college costs have skyrocketed. Both the share of students borrowing to finance their education and the average amount of borrowing have increased. States have withdrawn public investment in higher education, and many students from low- and middle-income families have been priced out of public colleges and universities. This has resulted in a decline in the college-going rate among low-income students and a dramatic slowing of the rate among middle-income students.

In “A Great Recession, a Great Retreat,” CAP proposed the creation of the Public College Quality Compact—a fund to encourage states to reinvest in postsecondary education. In addition to other requirements, states that wish to participate in the fund would be required to create reliable funding streams to public colleges and universities that provide at least as much as the maximum Pell Grant per student in support. Ensuring that states make reliable investments in their citizens will mean that college education is affordable for low-income students who pursue associate’s or bachelor’s degrees by guaranteeing grant aid to cover their enrollment at public institutions.

Affordable higher education is necessary but not sufficient

Making college more affordable is certainly essential. However, in order to meet short- and long-term economic needs, the higher-education system must be easier to navigate, as well as more transparent.

When students graduating from high school ask how much it will cost to go to college this year, they will likely hear “it depends.” If they are fortunate, soon-to-be high school graduates will learn about the net price of attending a particular college or university by looking at the information on the Department of Education’s College Navigator or College Scorecard or by looking for the net price calculators that colleges or universities are required to have on their websites. After soon-to-be graduates apply for admission, complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, and meet other requirements, they might get a Financial Aid Shopping Sheet or another type of financial aid award letter that tells them how much financial aid they will receive and how much they will need to pay out of pocket or borrow. For many low- and moderate-income students, particularly those from families where the student is the first to attend college, all of this information—or the lack of specific information—fails to convey the message that college is for you and that you can afford to go.

All high school graduates should be able to attend public two- or four-year college or university in their home states without having to worry about whether they can afford the tuition and fees. But how can graduates and their families pay for it?

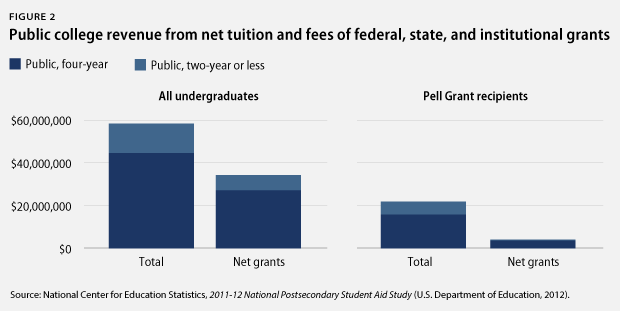

Colleges and universities, even public ones, need revenue to pay faculty and staff adequate wages commensurate with their own educational attainment and professional role, build and maintain facilities, and keep the lights on. But consider this: Total tuition and fee revenues at public two- and four-year colleges totaled less than $64 billion in 2013. Included in that total was tuition and fees paid by grants and loans.

Using data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ 2011–12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey, it is possible to estimate the net tuition and fee revenue from undergraduate students after all grants are applied. That analysis suggests that the net tuition and fee revenue received from public two- and four-year colleges and universities is substantially less. In the 2011–12 school year, two- and four-year public colleges and universities earned $58 billion in revenue from tuition and fees. But, after subtracting the grants provided, the net revenue was only $34 billion—or 59 percent of gross revenue. Among students receiving Pell Grants, the difference between the earned and net revenues was even more dramatic. Two- and four-year public colleges earned nearly $22 billion in tuition and fees from Pell Grant recipients, and they collected only $4 billion—or 19 percent of gross revenue from Pell Grant recipients. Meanwhile, with community colleges collected less than $500 million—or 8 percent of gross revenue—annually in tuition and fees. It is important to note that tuition and fees do not include additional student expenses such as room and board, books, supplies, and/or transportation, otherwise referred to as cost of attendance.

Replacing the net tuition and fee revenues paid by all Pell Grant recipients—or, for that matter, all undergraduates—is not outside the means or ability of the American people, particularly if this investment were made in partnership with states, as called for in “A Great Recession, a Great Retreat.”

A necessary investment in our future: College for All

In 2013, the Center for American Progress convened a transatlantic Commission on Inclusive Prosperity aimed at establishing sustainable and inclusive prosperity over the long term in developed economies, with a specific focus on raising wages, expanding job growth, and ensuring broadly shared economic growth. The commission was composed of high-level American and international policymakers, economists, business leaders, and labor representatives and was charged with developing new and thoughtful solutions to spur middle-class growth.

The Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity outlines an even more aggressive College for All plan to make education beyond high school universal without students or families having to come up with the funds to pay tuition and fees prior to enrolling either at a community college or a public four-year college or university in the United States. By taking such a step, all high school graduates and their families will know that they can afford higher education. College for All would provide every high school graduate financial support at a level up to the tuition and fees at a public four-year college or university. If students attend community college, they would receive an amount that would cover the cost of attendance. If a student attends a private college or university, the student would receive an amount equal to tuition and fees at the comparable public college or university in the student’s home state.

Under College for All, the type of aid each student could receive would vary based on their family’s long-term economic circumstance. Today, a family’s income in the past full calendar year immediately prior to enrolling in college is used to determine the amount and types of federal aid a student will receive. This assessment may, or may not, bear any relationship to the long-term economic health of the student’s family. Under the current system, the amount of aid provided often does not fully cover the cost, discouraging many low- and middle-income students from pursuing degrees or opting for the less expensive, lower quality options. In 2011–12, for example, students from the bottom income quintile faced average costs not met by grants and loans at public four-year colleges of nearly $6,700, or 58 percent of the average income of this group. Those at the second lowest income quintile faced costs of $7,600, or 26 percent of the average income of this group.

Students must repay much of the aid provided by the federal government, and that would continue to be true under the College for All plan. But repayment would depend on the graduate’s income and would be streamlined in that there would be only one payment made through the Internal Revenue Service. The repayment terms would be more generous for low- and moderate-income students than the current 10 percent or 15 percent of discretionary income earned each year after college. Like today under the income-based student-loan repayment plans, students would be required to repay only for a specified period of time—for example, 20 years or 25 years. Former students who are struggling economically would not be required to make payments until their earnings are sufficient. And similar to the payroll tax for Social Security, there would be a cap on the amount that an individual would need to repay. Finally, aid that does not have to be repaid, such as today’s Pell Grant or American Opportunity Tax Credit, would be retained but targeted at the most at-risk students at public and private colleges and universities.

Studies have suggested that the current financial aid system fails to reach its full potential because it is overly complex. Since those studies were completed, federal student aid programs have become significantly easier to access as a result of changes to the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. But it is likely still true that a radically simpler system that is easy to explain would show more robust impacts.

In the coming months, the Center for American Progress will be laying out the parameters of the new College for All proposal in a series of reports. These reports will address how an early guarantee of federal financial aid could eliminate barriers to a postsecondary education; how much the federal government would provide to cover costs at community colleges, public four-year colleges and universities, and private nonprofit and for-profit colleges; how those amounts will be determined; the levels of grant support that would be provided to low- and moderate-income students; and how the repayment terms will be structured. The reports will also address how much College for All will cost taxpayers and what the return on this investment will be. The overall goal of this endeavor is to ensure that the United States has the skilled workforce and educated citizenry to achieve inclusive prosperity and economic growth. College for All is radically student-centric and will significantly increase the college-attainment among students from low- and moderate-income families.

David A. Bergeron is the Vice President for Postsecondary Education at American Progress. Carmel Martin is the Executive Vice President for Policy at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Jessica Troe and Kate Hassey for providing valuable input and content for this report.