Introduction and summary

The U.S. education field rightfully prioritizes preparing students for college, their career, and the future of work, but it’s also important for students to be prepared to participate in their democracy.1 Active and engaged citizens have multiple things in common, including, but not limited to, civic knowledge and literacy as well as civic engagement through activities such as volunteerism, social-emotional learning, and voter participation.2 Civics education in K-12 schools provides a critical opportunity to introduce these activities to and build knowledge for students. To adequately prepare students to participate in their democracy, this civics education needs to, at minimum, robustly cultivate civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions.3

Unfortunately, civics education across the country has not always increased students’ civic knowledge and engagement, as federal and state funding for civics education has decreased over time.4 Although most states offer civics courses in middle school and high school—and some even mandate civics projects—since 1998, overall test scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) civics exam have persistently shown that less than 25 percent of students are proficient in the subject.5 What’s more, gaps persist between the scores of Black and Hispanic students and those of their white peers as well as by English language learner, income, and disability status.6 These NAEP scores may be explained in part by white students’ disproportionate access and exposure to civics education and engagement opportunities compared with African American and Latinx students; higher incomes also lead to more opportunities for engagement.7 It’s important to address this disproportionality, as improved civics education can lead to greater civic engagement, including the increased likelihood of voting.8 Subsequently, once a person votes, they are likely to become habitual voters.9

Civic engagement is defined as “working to make a difference in the civic life of one’s community and developing the combination of knowledge, skills, values and motivation to make that difference.” 10 This can include, but is not limited to, political activism, community and national service, volunteering, and service-learning.11 Specific opportunity gaps in civic engagement are similar to the disparities in NAEP civics scores between Black and Latinx students and white students as well as between students from lower- and higher-income families.12 For example, white youth are twice as likely as African American youth and three times as likely as Latinx youth to contact a public official.13 Additionally, students from families with low-incomes are “30% less likely to report having experiences with debates or panel discussions in their social studies classes.”14 This is not to say that communities of color or low-income communities are less interested in civic engagement but rather to acknowledge that disproportionate exclusion from civics education15—combined with other structural barriers such as voter suppression, voter disenfranchisement,16 and an understandable distrust of government17—can lead to decreased civic participation.18

Still, there are bright spots. While overall youth volunteerism rates have declined in the past 15 years, youth interest in community and student engagement has increased.19 When channeled and organized, this interest can lead to a groundswell of significant civic engagement through student activism. In 2018, for example, more than 1 million people rallied against gun violence in the youth-organized March for Our Lives20; in 2018, hundreds of thousands of young people participated in youth climate strike marches across the country.21 Young voters are disproportionately subjected to structural barriers to civic engagement such as voter suppression, voter registration requirements, rigid voting hours, and more.22 However, youth participation should be welcomed in our democracy, as it can inspire and cultivate immense change.

Youth voter turnout has historically been low in all elections but saw a 79 percent increase from the 2014 midterm elections to the 2018 midterm elections.23 Advocates for Youth described the phenomenon as a “youth wave … sweeping the nation,”24 and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement called youth a “powerful voting bloc in the 2018 midterms.”25 Youth civic engagement through protest, social movements, and voting illustrates how the United States and democracy only grow stronger when young people are civically engaged. In order to engage students effectively, relevant decision-makers—including practitioners and policymakers—need to herald and support civics education at the local, state, and national levels.

In February 2018, the Center for American Progress published an issue brief on the state of civics education in America, analyzing civics education requirements for all 50 states and the District of Columbia.26 With the wave of youth activism and engagement in 2018 and increased interest in civics education leading into the 2020 elections, the time is right to reexamine the state of civics education and look deeper at promising approaches to increase civic engagement. This report provides an updated state-by-state analysis of civics education requirements and civic engagement measures.

Key findings from the analysis

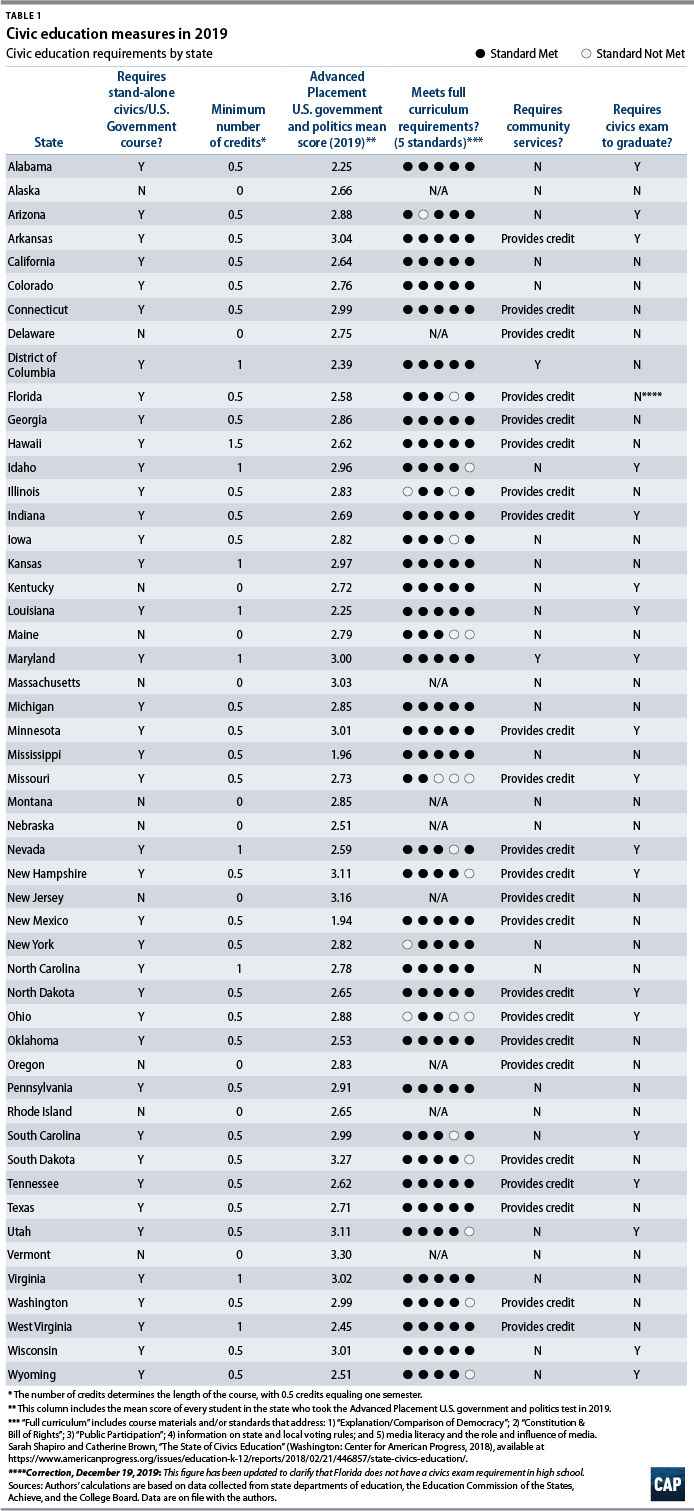

To garner a better understanding of the state of civics education, the authors examined state civics requirements based on several factors: whether states required a civics and/or U.S. government course; states’ minimum number of required civics course credits; if states required students to complete community service; states’ mean scores on the Advanced Placement U.S. Government and Politics (AP USGP) exam; if states required students to take a civics exam; and whether civics and/or U.S. government courses included five key elements of a robust curriculum. For added context, the five key elements of this full curriculum are course materials and/or standards that address the following: 1) an explanation or comparison of democracy; 2) the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights; 3) public participation; 4) information on state and local voting rules; and 5) media literacy and the role and influence of media. The first four categories were determined through research in the 2018 CAP brief cited above. To address the exponential increase of inaccurate media sources and their effect on civics education, the authors of this report added the fifth category to their analysis.

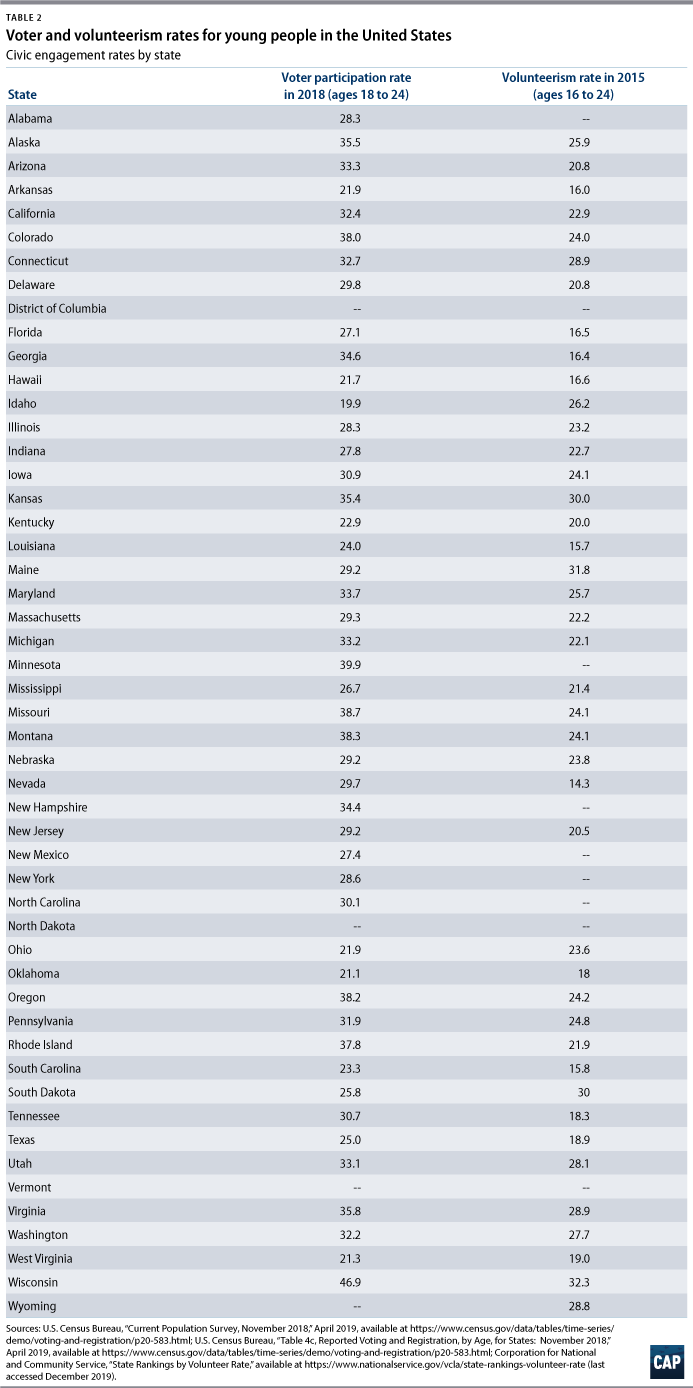

Tables 1 and 2 present the current civics education high school requirements by state.

The main findings of the analysis are as follows:

- Most states require at least a semester’s worth of standalone civics courses. Thirty states require 0.5 credit, which equals one semester, while eight states and the District of Columbia require one credit, or one full-year course. Hawaii goes above and beyond with 1.5 credits. It’s important to note, however, that some states such as Vermont27 employ proficiency-based graduation requirements, so they do not require any standalone courses. The goal of these requirements is to ensure that important standards are embedded in every grade from Kindergarten through 12th grade.

- Almost half the country requires students to take some sort of civics exam to demonstrate competency. Since 2018, two states—Indiana and Nevada—have passed new legislation to implement a civics exam graduation requirement, bringing the total to 20 states as of 2019. Notably, Kentucky is the only state without a civics course requirement; however, it still mandates that students complete a civics exam.

- About half of the country employs a robust civics curriculum and/or standards. A deep dive on curricula found that only 26 states met all five standards of the full curriculum, and 12 states met some variation of 4 out of the 5 standards. In total, 33 states addressed media literacy and the role/influence of media, something that hopefully improves students’ ability to identify inaccurate media sources and false content.

- Community service is rarely required. As of 2019, 23 states offer some type of academic credit for community service. However, as noted in the 2018 CAP issue brief, Maryland and the District of Columbia are the only two entities that mandate community service as part of their graduation requirements.

- There does not appear to be a clear relationship between course requirements, civics exam requirements, or curriculum standards and scores on the AP USGP exam. There are only 11 states with scores at or above a 3.0 on the AP USGP, and there is no commonality between their civics education measures. Additionally, the two states with the lowest scores both have a mandated course and meet the full curriculum requirements. There may be several reasons why there is no clear relationship between these factors, one of which being that AP courses are not offered in every high school.

Case study: Maryland’s successes in youth civic engagement

Maryland shines as an early investor in youth civic education and engagement. To demonstrate its commitment to civics education, Maryland codifies civics courses and content in social studies standards from pre-K to 12th grade.28 The state also mandates that specific civics course and project requirements be completed before students are eligible to receive their high school diploma. Public school students in Maryland must take at least one year of civics or government courses; complete 75 hours of community service; and achieve a passing score on the Maryland High School Assessment in American Government.29 Maryland is the first U.S. state to incorporate service-learning experiences into graduation requirements via its State Board of Education;30 this mandate incorporates student preparation and reflection to integrate existing academic course content into a project to aid students’ learning.31 Examples of previous projects include a drive to collect animal food and toys to combat animal cruelty32 as well as time spent fundraising for cancer research and advocacy efforts for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.33 Maryland’s average AP USGP score is a 3.0, placing it among the first quintile of states in the country.

Maryland’s efforts to increase youth civic engagement extend beyond civics education. Maryland was one of the first states in the country to preregister 16 and 17 years old to vote, ensuring that teenagers “are eligible to cast a ballot when they reach 18.”34 According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 23 states and the District of Columbia offer some form of preregistration before an individual turns 18 years old.35 The impetus behind preregistration is to involve prospective voters early and, subsequently, increase voter turnout for 18 to 29 year olds.36

In addition to preregistration, several Maryland cities have lowered the voting age to 16. While the voting age for federal elections is 18, the cities of Takoma Park, Greenbelt, and Hyattsville passed local measures to allow 16 and 17 year olds to vote in local elections. In 2013, Takoma Park made history as the first U.S. city to lower its voting age to 16.37 After the measure was passed that year, the voting rate of 16 and 17 year olds was double the rate of voters aged 18 and older.38 Hyattsville passed its measure in 2015,39 and Greenbelt followed suit in 2018.40 These actions came after youth lobbied and galvanized supporters and testified at their local city council meetings to encourage adoption of the measures.41 After Hyattsville passed its measure, the city created a Teen Advisory Committee to cultivate youth interest, strategize around youth-related issues, and develop recommendations for high-impact partnerships to serve youth and the Hyattsville community.42

Similar to advocates of preregistration, supporters of lowering the voting age argue that cultivating consistent voting habits among high school students will help improve overall voter participation when those students become adults.43 Maryland’s civics education investments and policy changes could be one component of a larger strategy to help improve engagement among Generation Z. The state’s 2018 youth voter participation rate was 33.7 percent, placing Maryland 12th among all states and the District of Columbia, and its 2015 youth volunteerism rate was 25.7 percent, placing the state 11th in the nation.44 Maryland stands out due to its legislative and curricular commitment to consistent civics education for students in every grade. Additionally, Maryland’s strategy to incorporate active civic engagement through service learning shows that civics education should turn into civic action, as discussed in the section below.

Strategies to strengthen civic engagement

Civics education is not limited to learning the branches of government or the U.S. Constitution. To be sure, state-required civics education is only one component of a multipronged effort to create an engaged and active citizen.45 While policymakers and practitioners can design civics courses to build civic knowledge and skills, they should also uplift strategies to strengthen student civic engagement and prepare students to fully participate in democracy.

Student strategies: Youth participatory action research and activism

Once students garner a robust civics education, it’s important that they are able to transform that knowledge into civic engagement inside or outside of schools through strategies such as youth participatory action research (YPAR) and youth-led activism.

YPAR and its principles are effective for all students, but they particularly uplift students of color and other traditionally marginalized identities such as students who identify as LGBTQ.46 Typically, teachers or community members train students to develop research questions around an issue of oppression in their schools or communities. These issues can range from Islamophobia in America47 to Black girls’ experience in the school-to-prison pipeline.48 Students conduct research through interviews, data collection, or another relevant method then analyze the results and develop adequate solutions.49 Afterward, students advocate for those solutions to relevant decision-making bodies, including school administrators and local and state policymakers.

In addition to YPAR, students can utilize another form of civic engagement: activism through protest. For decades, youth-led political activism in the United States has garnered social change. From the Freedom Riders protesting segregation policies in the early 1960s to Vietnam War protestors in the late 1960s and early 1970s, to anti-apartheid protesters in Los Angeles in the 1980s, youth civic engagement illuminates vital political issues. This is especially true for youth of color, who have been at the forefront of activism despite limited access to civics education and formalized civic engagement opportunities.50 Before the 2018 midterm elections, hundreds of thousands of students gathered across the country to elevate the need for gun violence prevention legislation through the March for Our Lives.51 In 2019, millions of young people in the United States and around the world gathered for the Youth Climate Strike to advocate for governmental action to address the climate crisis through both executive action and legislation, focused on eliminating fossil fuel use, reducing national and global greenhouse gas emissions, increasing K-12 education on climate change, and more.52

Sometimes activism starts with just one voice, as evidenced by Amariyanna (Mari) Copeny and Xiuhtezcatl Roske-Martinez. In 2016, at just 8 years old, Mari wrote a letter to then-President Barack Obama to protest the lead-contaminated drinking water in Flint, Michigan.53 Her individual civic engagement led to increased national attention on the Flint water crisis and played a large role in President Obama’s visit to the city.54 In 2015, at the age of 15, Xiuhtezcatl Roske-Martinez, an indigenous climate activist from Boulder, Colorado, testified before the U.N. General Assembly on the urgency of climate change.55 Xiuhtezcatl is the current youth director of Earth Guardians, a Colorado-based nonprofit that works across six continents to “train diverse youth to be effective leaders in the environmental, climate and social justice movements.”56 Xiuhtezcatl works with youth across the country and transforms their civic engagement into “action to protect the planet.”57 Both YPAR and activism through protest prepare students to become dynamic citizens as they channel youth civic engagement into social change both inside and outside of their schools.

Classroom strategy: News and media literacy education

To ensure students are prepared to be active citizens in the digital age, schools and policymakers need to help them cultivate media and news literacy with robust curricula. The Center for Media Literacy defines media literacy as the “ability to access, analyze, evaluate and create media in a variety of forms.”58 News literacy more specifically “focuses on growing engagement with the news, awareness of current events, and a deeper knowledge of the role of journalists.”59 Both news and media literacy are pertinent to students’ civics education today, as students may be inundated with unreliable information through social media and the internet, which harms their ability to effectively engage on key issues.60

With the increased availability of information online, students must be extra savvy to determine a source’s reliability, but it’s a difficult task. Discernment is not just a student problem, however: A 2016 Pew Research Center survey found that around 51 percent of U.S. adults see “at least somewhat inaccurate” information online, and about 16 percent of U.S. adults admitted to inadvertently sharing false political news online.61 Different efforts have been made to advance media literacy education, but students are still vulnerable to fake news.62 A 2016 Stanford University study found that middle school, high school, and college students struggled to discern the credibility and veracity of sponsored content and news sources.63 As of 2017, more than 150 million robot accounts on social media platforms have helped promote fake news.64 According to nonprofit organization Avaaz, fake news stories amassed about 159 million views in 2019, and interactions with fake news from August 2019 to October 2019 are around 1.5 times more than the media reported in the three to six months before the 2016 election.65 The increase of inaccurate news and lack of general civic knowledge on how the government functions allow disinformation campaigns to succeed, especially online.66 For example, a 2016 survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 26 percent of Americans could name the three branches of government.67 A 2017 survey by C-SPAN found that almost 60 percent of participants were unable to name a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.68 Yet students can be taught the necessary media literacy skills to effectively and carefully consume and produce news.69

California has passed legislation requiring the State Department of Education to offer school districts a list of online media literacy resources, instructional materials, and media literacy professional development programs for teachers.70 The bill will affect all K-12 students as of July 1, 2019; it aims to reduce confusion caused by fabricated news and increase access to media literacy education for underrepresented communities.71 On a national scale, the News Literacy Project (NLP), a national education nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., partners with more than 30 media organizations to offer students and teachers resources to increase news literacy.72 The organization offers teachers in-person and virtual professional development, connecting educators with journalists with whom they can discuss news literacy to increase students’ civic engagement.73 The NLP also offers Checkology, an online interactive platform that teaches students to identify source credibility and reliability. In the 2018-19 school year, 69 percent of students who used the platform could identify quality journalism, and 68 percent noted that they planned to be more civically engaged in their communities.74 In addition to creating a more robust civics education, components of news literacy show potential to increase current events knowledge, internal political efficacy, and cultivate positive relationships with civic life.75

National strategy: Increasing voter registration and participation

Besides preregistration for 16 and 17 year olds, strategies to cultivate youth civic engagement through voting can include high school registration drives, larger business strategies, and organizing to combat voter suppression tactics.

Organizations such as the League of Women Voters Education Fund offer training manuals on how to implement high school voter registration programs while centering historically underrepresented populations such as those without a college education and those in communities of color.76 Virginia even offers a high school voter registration challenge in which high schools across the state compete to register the largest percentage of voting-age students and receive a certificate from the governor.77 These efforts bring K-12 civic education to life by underscoring the importance of being an informed, active citizen.

On a larger scale, businesses such as Snapchat, a mobile messaging app, turned youth engagement into civic action by registering voters before the 2018 midterm election. Snapchat added links for voter registration to users’ profiles and sent them video reminders which resulted in more than 400,000 new voter registrations.78 Additionally, in response to increased misinformation, Snapchat—unlike other social media platforms—currently checks political ads for accuracy.79 Relatedly, Spotify, a music streaming service, exerted its own civic engagement efforts to get voters to the polls by providing customized state playlists as Election Day approached in November.80 While Snapchat and Spotify are organizations that exist outside of schools, they overwhelmingly capture the attention of Generation Z81 and Millennials,82 the current and next generation of youth voters.83

While increased civics education and engagement can improve voter registration rates among young people, these efforts are futile if voter suppression measures—which disproportionately affect young people and people of color—prevent them from voting once they turn 18.84 Young people and voting advocates have joined forces to fight back against nefarious attempts to depress youth turnout by challenging many discriminatory voting laws in the courts. For example, a Wisconsin law making it harder for college students to rely on their student IDs as a form of identification prior to voting is currently being challenged in court.85 Similarly, students at Prairie View A&M University, a historically Black university in Texas, are suing Waller County after noticing that their school was restricted to only three days of early voting in 2018, compared with the two weeks allotted to other parts of the county and the nearby majority-white Texas A&M University.86 In Florida, officials tried to ban early-voting sites at state universities in 2014, but their efforts were blocked by a federal court in 2018 after being deemed unconstitutional.87 Strict voter ID laws, polling closures, and voter purges particularly affect youth voters, especially those who are Black, Native American, and Latinx.88

Despite these efforts, organizations such as Fair Fight aim to combat voter suppression through civics education activities, lobbying, and voter registration and outreach programs.89 Fair Fight specifically highlights the voter suppression tactics that target communities of color and young voters as insidious efforts to subvert the U.S. democracy.90 Although the organization’s work is based in Georgia and the upcoming 2020 election, Fair Fight is expected to target 20 states that have also historically disenfranchised communities of color and/or young people.91 Challenging voter suppression tactics is a prime use of civic skills that can be taught in K-12 schools. Creating strategies to increase voter registration and access to polling locations illuminates the importance of civics education’s role in perpetuating civic behaviors and engagement.

Conclusion

Our democracy is facing an unprecedented challenge. With an increased amount of fake news online and continued voter suppression efforts, it is imperative that students have a robust civic education. This includes a combination of offering standalone civics and/or government courses; a full curriculum that includes news and media literacy; and concretized opportunities for civic engagement. Additionally, when K-12 schools enable civics education to turn into civic action, students see the importance of becoming effective citizens and active participants in their democracy. Although Black and Latinx students and students in low-income communities have to navigate barriers to civic life and civic engagement that include voter suppression efforts and disenfranchisement, civics education can help ease these barriers through the cultivation of strong civic skills and dispositions. Moreover, by utilizing strategies such as YPAR, schools are more likely to engage historically marginalized students and communities to help increase civic participation. Students can build on the civic knowledge they have gained in the classroom by volunteering or demonstrating activism through protest. Cities and states can help empower youth and civic participation by lowering the voting age, offering preregistration, and maintaining high school voter registration drives.

As the 2020 elections approach, there will be continued disinformation campaigns,92 and prioritization of news literacy by educational institutions is one component of a promising strategy to combat them.93 American youth must be civically educated in order to discern fact from fiction and remain invested in the state of their democracy. They must also be adequately prepared to lead the nation toward essential civic and social change at the local, state, and national levels.

About the authors

Ashley Jeffrey is a policy analyst for K-12 Education Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Scott Sargrad is the vice president of K-12 Education Policy at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Danielle Root, Lisa Smith, Morgan Spivey, and Andrew Wilkes for their invaluable input toward this report.