A humanitarian refugee situation at the U.S. southern border has been unfolding over the past few years and dramatically intensifying over the past several months, as tens of thousands of unaccompanied children are fleeing their homes in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. In search of a safe haven, these children embark on dangerous journeys, arriving in the United States and neighboring countries throughout Central America. Indeed, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, asylum applications from children are up by 712 percent in the neighboring countries of Mexico, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Belize. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) has argued that “many of the children apprehended at the border are fleeing unspeakable violence in their home countries.”

Even as the Obama administration struggles to deal with the situation, including finding adequate shelter and protection for the kids, some in Congress have attempted to score political points by arguing that the increased numbers are the result of the administration’s own immigration enforcement policies, such as the creation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program in 2012, which grants eligible unauthorized youth a two-year reprieve from deportation and a work permit. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA), for example, called on President Barack Obama to end the DACA program and begin deporting those with the status to send a message to prospective child refugees that they should not come to the United States. However, a close statistical evaluation of the available data suggests a very different dynamic that is leading children to leave their Central American homes. It is not U.S. policy but rather violence and the desire to find safety that is the impetus for these children’s journeys.

An analysis of the available data suggests that:

- Violence is among of the main drivers causing the increase. Whereas Central American countries that are experiencing high levels of violence have seen thousands of children flee, others with lower levels of violence are not facing the same outflow.

- By contrast, the evidence does not support the argument that DACA or lax border enforcement has caused the increase in children fleeing to the United States.

Violence is causing children to flee Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador

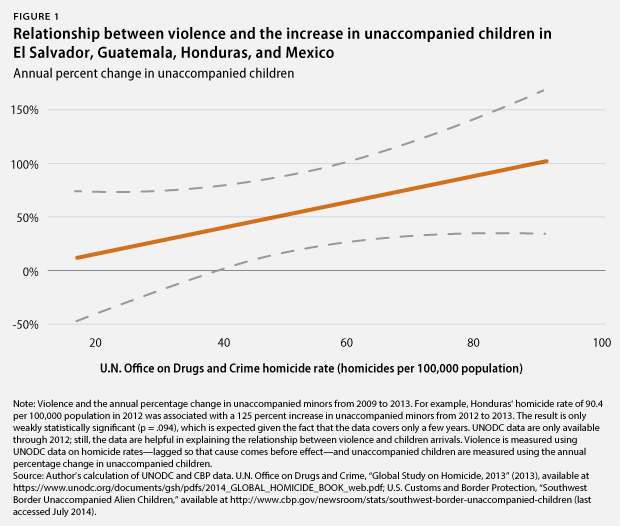

How can it be determined that violence is a primary factor causing children to flee? One way is to use the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, or UNODC, data on homicides and homicide rates by country. Coupling this data with that of the number of children arriving each year allows us to examine the relationship between violence and children arrivals.

Figure 1 shows how violence affects the flow of children. The relationship is positive, meaning that higher rates of homicide in countries such as Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala are related to greater numbers of children fleeing to the United States.

Another way to examine the relationship between violence and unaccompanied children is to use the data on security levels in Latin America compiled by FTI Consulting, a global business advisory firm headquartered in Washington, D.C. The annual index ranges from 1 (safe) to 5 (very dangerous) for each country, and data are available from 2009 to 2014. Here again, the relationship is positive, meaning that more dangerous security conditions are related to greater numbers of unaccompanied children. Using the FTI Consulting index data provides an even more strongly statistically significant result, suggesting an even clearer link between violence and children fleeing.

Not only do countries with the highest rates of homicide have the largest numbers of unaccompanied children fleeing, but the data also make clear that countries in Latin America with lower rates of homicide are not sending large numbers of unaccompanied children.

In 2012, the countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico accounted for 41,828 homicides, at a rate of 28 per 100,000 people. Exclude Mexico and the murder rate jumps to 54 per 100,000 people. The president of Honduras has gone as far as calling the children refugees from “war” in his country. By contrast, other countries in the region, such as Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama had a total of just 1,881 murders, at a rate of only 13 per 100,000. Nicaragua is particularly useful as an example: It is the second-poorest country in the region—behind only Haiti—and yet, with far lower rates of violence than the three main sending countries, it has not seen an uptick in unaccompanied children leaving.

These findings reinforce a report released by DHS that shows that many of the unaccompanied minors who have recently arrived come from some of the most dangerous cities in Central America.

DACA or lax border enforcement is not to blame

DACA

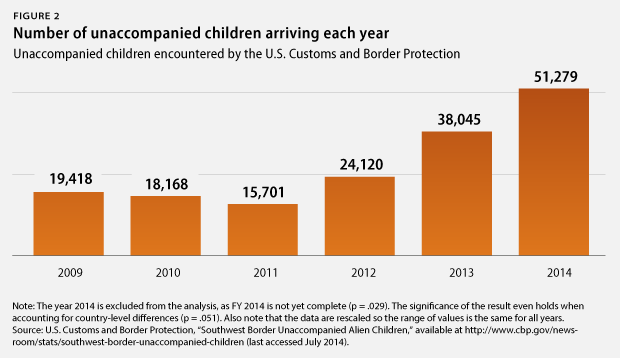

In fiscal year 2009, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, encountered slightly fewer than 20,000 unaccompanied children from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. So far in FY 2014, more than 51,000 children have entered, with the increase almost entirely coming from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. (see Figure 2)

The sharp increase during FY 2012 has been used by senators such as Ted Cruz (R-TX) to argue that the creation of the DACA program in June 2012 is the reason “that we have seen the number of children taking the incredible risks entailed with coming across the border grow exponentially.”

There are two problems with this line of thinking. For one, the increase in unaccompanied children began well before 2012. CBP estimates that between 2008 and 2009, for example, there was a 145 percent spike in unaccompanied children arrivals, jumping from 8,041 to 19,668.

But even more importantly, the U.S. fiscal year starts on October 1 and ends on September 30 of the following year. This means that FY 2012 actually started in October 2011 and ended in September 2012. Considering that applications for deferred action could only be submitted starting on August 15, 2012, it is highly unlikely that DACA caused an increase in children. Data on monthly border apprehensions—which admittedly do not distinguish between unaccompanied children and all others caught at the border—show that the number of people caught at the border actually slowed in the months after DACA was announced.

Border enforcement

Arguments such as those of Sen. Cruz connecting DACA to the increase in unaccompanied children also cite lax border security by the Obama administration as an additional contributing factor. But these arguments, such as those about DACA, are equally unsupported by the data. To give just a few examples:

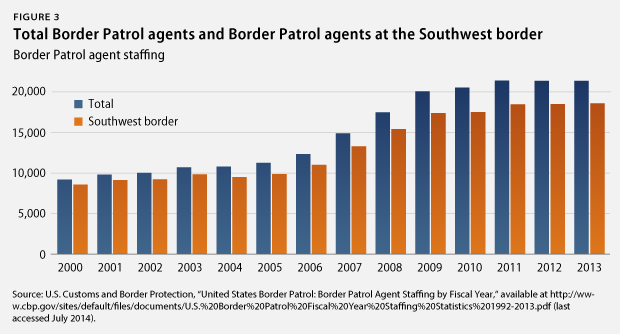

- Under the Obama administration, funding for the Border Patrol has reached record levels, increasing from $2.3 billion at the end of the Bush administration in 2008 to $3.5 billion in FY 2013—an increase of 52 percent.

- The number of Border Patrol agents in general, and at the southwest border, now stand at record levels. (see Figure 3)

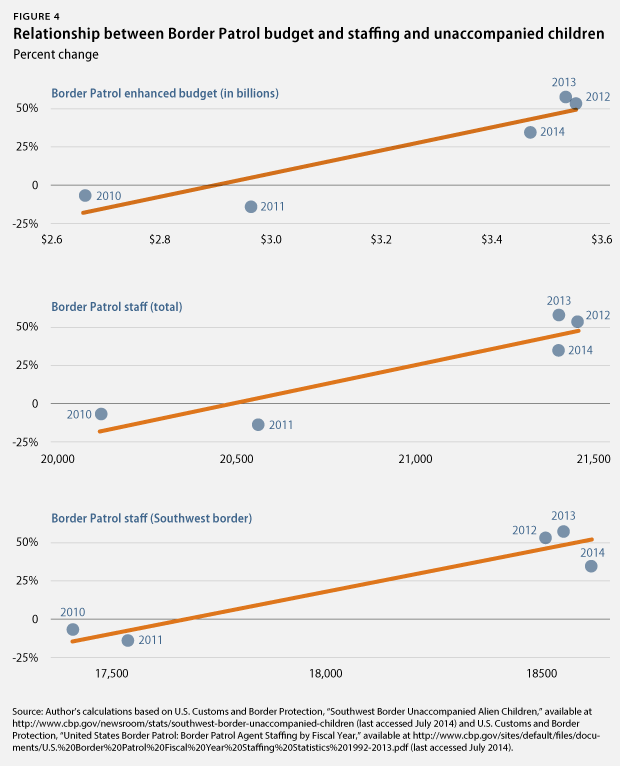

If lax border security were contributing to the increase in children arriving, we would expect to see a negative relationship between border security metrics and the number of unaccompanied children entering the United States. To put it another way, we would expect more children to arrive as border security efforts decrease. Instead, the opposite has occurred: As the United States has ramped up its border enforcement, more children have come. (see Figure 4)

To be clear, this should not be interpreted to mean that more border security means more unaccompanied children—again, we only have a handful of observations to analyze. Rather, the data suggest that the recent increase in unaccompanied children is not the result of lax border security, but is occurring despite record levels of border security spending and staffing.

And from recent press reports, it is clear that our border security policies are working exactly as intended: Numerous stories note that the Border Patrol is apprehending these kids upon entry, or soon after. Here too, the evidence is clear that border enforcement policies are not driving the surge in unaccompanied children.

Conclusion

Instead of attempting to repeal programs such as DACA, the United States should—as Sen. Robert Menendez (D-NJ) has suggested—ensure that these children are safe and secure, go after the smugglers and traffickers bringing them here in the first place, and seek solutions that help quell the violence in these children’s home countries. The data show that this situation is a humanitarian and refugee issue, not an immigration issue, and all sides must not lose sight of the children themselves who are at the heart of the matter.

Tom K. Wong is an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego.