As the national debate over the president’s plan to expand deferred action for close to 5 million people plays out in the courts, state legislators are proposing legislation regarding undocumented immigrants’ access to higher education. Since the beginning of the year, at least 12 states have introduced legislation on their tuition-equity policies, which determine access to public colleges and universities for undocumented students. More bills are anticipated in other states.

Although many of these bills make it easier for undocumented students to access postsecondary education, some states have tried to roll them back. Conservative legislators argue that it is unfair for taxpayers to subsidize undocumented immigrants’ higher-education costs, despite the fact that tuition-equity policies have helped thousands of undocumented students receive higher education. They must be protected and expanded.

Efforts to repeal undocumented students’ access to in-state tuition and state-sponsored financial aid at public colleges and universities gained traction in Texas following the 2014 elections. Newly elected Gov. Greg Abbott (R) and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick (R) have indicated their support for repealing or substantively diminishing the state’s tuition-equity laws. The repeal effort is ironic; Texas became the first state to allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition rates to attend public colleges and universities in 2001, when it adopted H.B. 1403 under a Republican governor and legislature. In 2005, Texas enacted S.B. 1528, which allows undocumented students to qualify for state-funded educational financial aid. Collectively, these two laws are known as the Texas DREAM Act.

This year, however, Texas representatives introduced H.B. 209, which would strip the state’s undocumented students of the opportunity to apply for in-state tuition. H.B. 306, meanwhile, would require these students to show proof of citizenship or lawful residency to qualify for in-state tuition. If Texas were to repeal its DREAM Act, it would be the largest state to take such action, but not the first; Wisconsin did so in 2011.

The need for state action

In 1996, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which restricted states’ ability to provide residency and in-state tuition benefits for undocumented students. Specifically, the law prohibits states from making undocumented students eligible for any postsecondary education benefit on the basis of state residency unless a U.S. citizen from another state would also be eligible for that benefit. Additionally, under the Higher Education Act of 1965, undocumented students do not qualify for federal financial aid for higher education, including Pell Grants, the federal work-study program, and federal loans.

With its DREAM Act, Texas led the way in defining a path for undocumented students to access higher education. Thanks in large part to sustained undocumented-youth activism, at least 18 other states now have provisions that allow undocumented students to access in-state tuition rates. While only three states currently allow undocumented students to receive taxpayer-funded educational financial aid, the number of undocumented students attending institutions of higher education in Texas has increased over the past decade. According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, the number of students who fell under the Texas DREAM Act residency provisions totaled 9,062 in fall 2007, more than 16,000 in 2011, and just more than 20,000 in 2012.

These efforts have allowed thousands of undocumented young people to attend institutions of higher education and get higher-paying jobs, particularly after President Barack Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program in 2012. The program allows undocumented young people to receive a temporary deportation deferral and gives them access to renewable work permits.

The impact of the Texas DREAM Act

Currently, the Texas DREAM Act extends in-state tuition and financial aid grant eligibility to noncitizen state residents if the following requirements are met:

- Students lived in Texas during the three years prior to graduating from high school or receiving a GED

- Students lived in Texas during the year before enrolling at a Texas public college or university

- Students sign an affidavit declaring their intention to apply for legal permanent resident status as soon as possible

These residency requirements have allowed thousands of otherwise ineligible undocumented students to pay in-state tuition rates and receive financial aid. The requirements also allowed Texas to bypass the restrictions on in-state tuition established by the 1996 federal immigration law.

Of the 1.3 million students enrolled in Texas public universities and community, technical, and state colleges during fiscal year 2012, 20,049—or 1.1 percent—benefited from the Texas DREAM Act and paid more than $40 million in tuition and fees toward higher education. Meanwhile, only 2,819 Texas DREAM Act students received state-sponsored grant aid at a cost of $9.56 million—just 2 percent of the more than $430 million in state-supported grants distributed to more than 130,000 students across the state.

These small costs also do not take into account the enormous tax contributions made by undocumented immigrants. In 2010, undocumented Texas residents paid more than $1.6 billion in state and local taxes, a portion of which went toward supporting Texas’ public colleges and universities.

Furthermore, a recent report by the University of California, Los Angeles, Institute for Immigration, Globalization, and Education showed that more than 55 percent of undocumented students were concerned about financing their education. Nationwide, the out-of-state tuition rate is 61 percent higher on average than the in-state tuition rate—too high for many undocumented students. In addition to making higher education more affordable, tuition-equity legislation has been shown to increase high school graduation rates for undocumented students, who are finally able to see higher education as a possibility.

The growing divisions between the states

Texas legislators are not the only ones attempting to roll back tuition-equity policies. State legislators in Kansas have proposed a bill to roll back tuition-equity laws for undocumented students. Additionally, advocates in Virginia recently defeated a legislative effort that would have stopped a decision by state Attorney General Mark Herring allowing DACA students to qualify for in-state tuition at public colleges and universities. Despite these challenges to tuition-equity legislation, legislators in California, Massachusetts, Georgia, Connecticut, New York, Mississippi, Indiana, Tennessee, and New Jersey have proposed tuition-equity policies to expand undocumented students’ access to higher education.

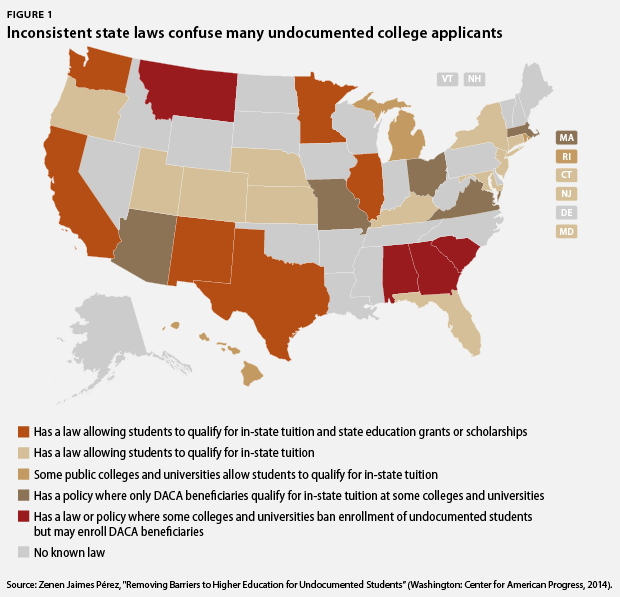

These state actions mean that in order to attend and complete a postsecondary education, undocumented students must navigate a host of state and federal laws, as well as the policies of individual institutions. Navigating this policy morass—along with other challenges—means that fewer undocumented students actually complete higher education.

The wide inequality between states

Some states have actively taken steps to remove barriers that undocumented students face in accessing higher education. However, some states still have policies that prohibit these students from enrolling in public colleges and universities.

California

- The California state legislature passed A.B. 540 in 2001, which allows qualifying undocumented students to pay in-state tuition.

- In 2013, the legislature passed A.B. 131, known as the California DREAM Act. The law allows all students who are exempt from nonresident tuition and deemed to be in financial need to qualify for all types of financial aid.

- The legislature passed S.B. 1210 in 2014, which allows a student attending a participating campus of the University of California or The California State University to receive a DREAM loan to help pay for college.

Georgia

- The Georgia General Assembly passed S.B. 492 in 2008, which bars undocumented immigrants from receiving in-state tuition benefits.

- The Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia adopted policy 4.1.6 in 2010. This policy prohibits most selective institutions—schools that do not admit all applicants—from admitting undocumented students.

The broken immigration system has caused some states to try to remove barriers to higher education, while other states seem happy to support them. This problem will only get worse: The four states with the fastest-growing undocumented populations—North Carolina, Georgia, Nevada, and Arkansas—also have the most restrictive tuition-equity policies.

Undocumented students need support

States must work to expand tuition-equity policies to make sure that undocumented students get a fair chance to earn a postsecondary education. Repealing the Texas DREAM Act would have enormous negative consequences for the thousands of students who depend on it to pay for their education. The influential Texas Association of Business has spoken out against its repeal, arguing that such action would have a negative impact on the state economy because undocumented young people would not have the opportunity to get an education and succeed in the workforce. A postsecondary education allows undocumented immigrants to more closely align their interests and skills to higher-paying jobs; they can then earn more money and start contributing more in payroll taxes. Such revenue supports vital programs such as Social Security and Medicare, even while undocumented immigrants are unable to benefit from these and other social safety net programs.

All students deserve a chance to access higher education regardless of their immigration status. While Congress should support immigration reform to address many of the challenges that undocumented students face, it is also critical for states to create policies that allow these students to access higher education.

Zenen Jaimes Pérez is the Senior Policy Analyst for Generation Progress at the Center for American Progress.