Despite years of economic growth, many Americans’ pay has not improved. Since the Great Recession, overall wage growth has only slightly outpaced inflation, and the earnings of African Americans have still not recovered. Meanwhile, business startup rates are falling across all industries, and many economists argue that this decline is dragging down U.S. innovation and productivity growth. As a result, policymakers across the United States are interested in reforms to boost worker pay, increase job mobility, and enable Americans to start their own companies. In particular, state lawmakers are debating actions to protect workers from restrictive employment contracts that keep them locked in jobs they do not want but cannot leave.

From fast-food workers and check-cashing clerks to physicians and engineers, corporations are increasingly subjecting workers across income and educational attainment levels to agreements that restrict future employment. One recent survey found that nearly 1 in 5 U.S. workers report that they are currently subject to a noncompete agreement that prevents them from moving to a competing employer, while another found that more than half of corporate franchisors require franchisees to sign no-poaching agreements that prevent their workers from moving between locations.

But the damage of these agreements extends beyond mobility impacts for individual workers. The wages of all workers are lower in states where corporations have maximal power to enforce noncompete agreements. Moreover, several studies indicate that strengthening noncompete protections for workers is associated with an increase in patents and firm startups—and that doing so could help new firms to attract top talent.

Although federal action on this issue is unlikely in the near term, state lawmakers have considerable power to protect low- and middle-wage workers from abusive employment contracts. For example, Illinois and Massachusetts have enacted laws in recent years to protect low-wage workers from noncompete agreements, and Washington state Attorney General Bob Ferguson is leading a fight to stop corporate franchisors from requiring their franchisees to sign no-poach agreements.

This primer—based on a 2019 Center from American Progress report, “The Freedom to Leave: Curbing Noncompete Agreements to Protect Workers and Support Entrepreneurship”—provides important background for lawmakers and advocates who are interested in strengthening state-level noncompete and no-poach protections. First, it provides a brief explanation of how noncompete and no-poach contracts are reducing wages and harming growth. It then details policy recommendations that states can adopt to protect workers from abusive agreements. Finally, the primer includes a table that illustrates how each state’s existing laws compare with CAP’s recommendations.

How do noncompete and no-poaching agreements restrict workers’ mobility?

A noncompete agreement is a contract that requires a worker to agree not to become an employee of a competing company or start a competing company for a specific period of time after leaving a firm. Typically, corporations require a worker to sign such an agreement at the start of a new job or position. Workers often receive little advanced warning of the requirement, usually get no payment during the waiting period, and—even if they suspect that an agreement is illegal—have little recourse to fight in the courts since legal remedies in these cases typically do not require employers to pay penalties or back pay to aggrieved workers.

As a result, research finds that these agreements have a significant impact on job mobility. Academic research found that job mobility in Michigan fell by 8 percent after the state started allowing the enforcement of noncompete agreements. Meanwhile, a 2017 U.S. Census Bureau paper found that tech workers in states that enforce noncompete agreements had 8 percent fewer jobs over an 8-year period compared with workers in states that do not allow enforcement of noncompete agreements.

No-poaching agreements lead to similar mobility restrictions on fast-food and other franchise workers, but without workers’ prior knowledge. These agreements are often included in voluminous and confidential contracts that corporations require individual franchisees to sign in order to operate a business under the corporation’s name. Workers typically find out about this limitation when they attempt to move to another store in the franchise chain that provides better career advancement opportunities, hours, pay, or working conditions.

State attorneys general are adopting strategies to aggressively enforce existing state laws in order to prevent the use of franchise no-poaching agreements. They argue that these agreements violate state and federal antitrust laws that were enacted to prevent anticompetitive practices such as employers from colluding to keep wages low. Yet corporate franchises often claim that a franchisor and its franchisees should be held to a different standard since they function as a single entity rather than as competitors.

How are noncompete and no-poach agreements reducing all workers’ wages?

When workers are subject to these sorts of agreements, their ability to bargain for better wages is reduced since they cannot leave a job for a competitor or to start their own company. While corporations have long required that CEOs and top talent sign agreements not to join rival firms for a certain period of time, today more than 38 percent of workers across all educational levels—and 35 percent of those without a college degree—report signing a noncompete agreement at some point in their lives. Moreover, barring franchises from recruiting the skilled employees of another franchise can drive down workers’ wages in industries where wages are already very low. For example, fast-food cooks earn an average hourly wage of $10.39 per hour, or $21,610 annually, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The prevalence of these agreements harms all workers. According to a 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Treasury, living in a state with strict enforcement of noncompete contracts, compared to one with the most lenient enforcement, is associated with a 5 percent reduction in pay for a typical 25-year-old worker—and this penalty grows to 10 percent for the typical 50-year-old worker.

Even in California—where courts are not permitted to enforce noncompete agreements—corporations require workers to sign them at rates similar to those of workers in other states, perhaps because of the agreements’ chilling effects on job mobility and wages. Indeed, to support robust wage growth, state lawmakers must not only tackle how courts enforce noncomplete laws but also support policies to ensure that workers are not forced to sign these agreements in the first place.

How are restrictive employment contracts harming entrepreneurship and regional growth?

Allowing workers to move easily between firms can help stimulate the economy as a whole by fostering innovation through information-sharing; entrepreneurship as workers leave jobs to start new companies; and even regional industry development—since firms can co-locate to share local talent pools.

Conversely, the negative consequences of limiting job mobility through strict enforcement of noncompete agreements can spread throughout a state’s economy. For example, studies have found that stricter enforcement of noncompete agreements reduces the number of new firms entering a state, lowers firm survival rates, reduces startup size, and even delays entrepreneurship among women. Moreover, a 2011 study reviewing nine years of data found that venture capital funding had stronger positive effects on the number of patents licensed and firm startups in states with weaker enforcement of noncompete agreements.

Finally, strict enforcement of noncompete contracts can deplete local talent pools by requiring skilled workers to leave their industry of expertise or relocate out of state to avoid geographic restrictions. For example, a 2011 study of engineers found that about one-third of workers who signed noncompete agreements left their chosen industry when they changed jobs.

What should states do to better protect workers?

To help raise wages and jump-start entrepreneurship, state policymakers should take the following steps, as detailed in the aforementioned “Freedom to Leave” report: ban noncompete agreements for most workers, ban franchise no-poaching agreements, and give workers and enforcement agencies the tools they need to enforce their rights.

1. Ban noncompete contracts for most workers

States should limit noncompete contracts to the small portion of workers with the power to bargain over these agreements. In order to protect low- and middle-wage workers, states should ban these types of contracts for all workers earning less than 200 percent of the state’s median annual wage. In addition, lawmakers should prohibit companies that employ at least 50 workers from requiring more than 5 percent of their workforce to sign such a document. These protections should extend to independent contractors as well.

2. Ban franchise no-poaching agreements

States should ban all no-poaching agreements among franchises. While several state attorneys general, under the authority of existing state antitrust laws, are taking action against fast-food corporations and other corporate franchisors that require franchisees to sign no-poaching agreements, clarifying legislation would help to ensure that courts do not rule against workers in the future and that corporations understand that no-poaching agreements are banned in all forms.

3. Give workers and enforcement agencies tools to enforce their rights

Existing laws place a considerable burden on workers to both know their legal rights and be willing to take on a former employer in court in order to protect themselves. States should empower workers to stand up for themselves and should bolster enforcement agencies’ ability to protect workers by requiring companies to disclose all noncompete requirements in job postings and job offers; establishing significant penalties for use of illegal noncompete and no-poaching agreements; designating and funding enforcement agencies to pursue these sorts of cases; and allowing workers to sue companies that violate their rights.

How do existing state laws stack up?

Lawmakers in several states—including Maine, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and Washington—are debating policies to protect low- and middle-wage workers from exploitative noncompete agreements and to ban franchise no-poaching agreements.

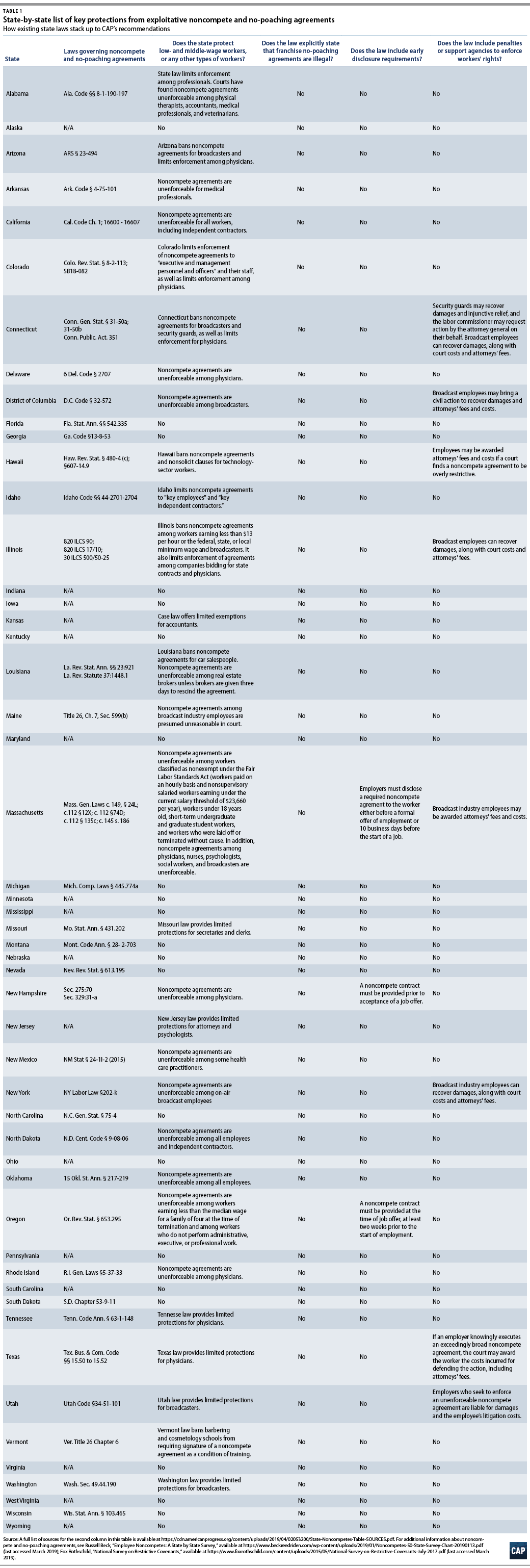

To help advance this debate, CAP reviewed existing state statutes governing these kinds of agreements; some—but by no means all—major cases on the topic; and numerous resources that summarize how state courts have interpreted statutes and existing case law governing restrictive contractual agreements. The table below represents CAP’s effort to detail how existing state statutes and case law stack up to CAP’s recommended reforms.

No state goes far enough under existing laws to protect workers from abusive noncompete and no-poaching agreements. For example, CAP was unable to find any existing state laws that clarify that franchise no-poaching agreements are illegal. Moreover, most existing state laws that regulate noncompete agreements focus on how courts should adjudicate legal disputes or protect only a small subset of workers, rather than banning these sorts of agreements in the first place.

Finally, it is important to note that while a few states have enacted laws that explicitly allow workers who are subject to exploitative agreements to collect penalties, more general state labor protections—which are not the focus of this table—may help provide workers some recourse. For example, California has enacted a number of laws to ensure that workers can pursue claims against employers in state courts and are not forced to sign away their rights. State lawmakers can boost wages and encourage entrepreneurship by banning contracts to restrict workers’ job mobility. While lawmakers should closely review existing state laws, this resource is a useful tool for lawmakers and advocates working to spark debate and implement these sorts of reforms.

A downloadable version of this table is available at https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2019/03/29105833/State-Noncompetes-Table.pdf.

A full list of sources for the second column of this table is available at https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2019/03/27132622/State-Noncompetes-Table-SOURCES.pdf.

Karla Walter is the director of Employment Policy at the Center for American Progress.