The failures of the Trump administration to deploy a transparent and effective national-level response to the coronavirus, which causes the disease COVID-19, means that state and local governments are left picking up the pieces. While the public health response is the most urgent, the economic response will be no less challenging. The rapid, large-scale measures that will be needed to blunt a recession will be impossible without federal support that engages state and local governments’ greater capacity and person-power. Yet there are basic policy steps that state and local policymakers can take immediately to help local economies and working families weather the storm.

A public health-driven economic crisis is different

A public health crisis has unique impacts on the economy and worker economic security. First, it hits supply and demand simultaneously and across many markets and regions. Consumers may be afraid to shop or go to entertainment venues. Workers may be unable to work if workplaces, schools, or child care centers are shut down, or if they are sick or exposed to the virus. Supply chains are disrupted, limiting production. Overall growth and business confidence can crater. The economy could grind to a near-halt in heavily affected industries and geographic areas owing to the need to quarantine to stop the pandemic.

This economic fallout is similar to a natural disaster, whereby businesses and people have little control over whether they will be affected by the virus and its economic ripple effects. It is also made worse by spillover effects such as credit market disruptions, misinformation, and herd behavior that make it look like a financial crisis. In the case of COVID-19, add in the racism arising from the disease’s origin in Asia, and businesses in U.S. Chinatowns have already seen disproportionate and undeserving economic hits. With its fewer resources, rural America is hit as well.

As with both natural disasters and financial crises, addressing the underlying problem is essential to getting the rest of the economy going again. For a natural disaster, the physical environment has to be safe enough to rebuild. For a financial crisis, the risk of bank and credit market runs have to be removed, and bad debt has to be recognized so that people and businesses can get access to credit again when they need it. In this case, this means that governments, especially at the state and local level, will need to do whatever they can to contain the public health crisis and manage the economic knock-on effects. A wide range of additional work will need to be considered at every level of government to confront supply chain shortages and boost economic and public healthy resiliency.

States play a key role in local economies

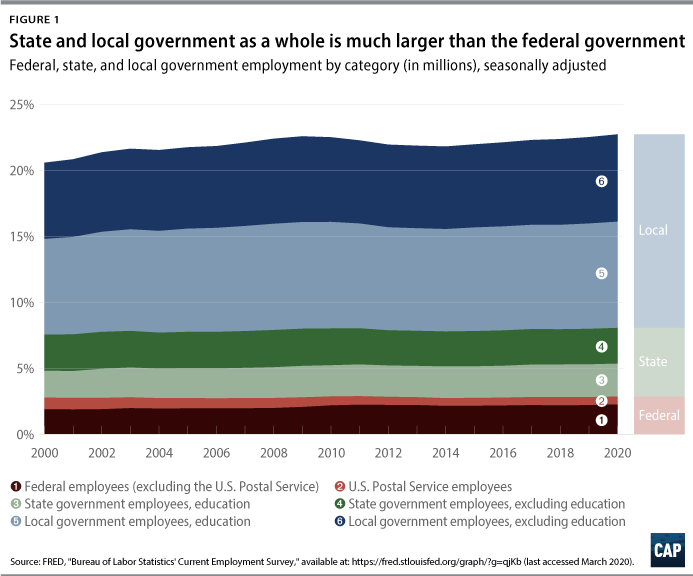

States and local governments are on the front lines of supporting the economic livelihoods of their residents. Many federal programs—health insurance, unemployment insurance, housing supports, transportation spending, and more—are administrated through states and localities. This uniquely American arrangement means state and local governments are much larger than the federal government in size, employing 10 times as many workers, and maintaining information, programs, and systems critical to an economic response.

Small business impacts may be severe

One of the first ways COVID-19 can hit a local economy is through its small and medium-sized businesses. Nearly 60 million Americans—more than 47 percent of workers—work for a business with fewer than 500 hundred employees. Nearly one-quarter of these businesses are in accommodation, food services, and retail trade—sectors that are likely to be laying people off due to lower demand and where the jobs are already usually low wage and cannot be done remotely. Reports are already trickling in that small businesses are finding themselves suffering economic hardship, with Asian American businesses some of the earliest and hardest hit. Small businesses often struggle to build up cash reserves that will get them through a rough patch.

Amid the fallout from the virus, as the cash flow squeeze on these businesses becomes severe, they would have to decide whether to borrow on their lines of credit (often credit cards) or partially or fully furlough their workers. Those workers in turn could have a hard time paying their rent or buying food. Unlike an ordinary recession, where fiscal stimulus—if large enough and sustained—could put workers and small businesses back to work, a public health scare could leave workers and businesses physically stranded for days or weeks, unable to earn or spend money. State and local governments could then face very serious housing, food security, and related crises.

The effect of the virus on the economy will show large regional variations

Right now, the virus affects the economy in particular areas. Governments’ responses to the spreading illness have shut down factories abroad and disrupted supply chains for domestic manufacturers. Travel restrictions and self-imposed social distancing threatens travel, especially air travel, conferences, and tourism. States and localities that more heavily depend on manufacturing, tourism, and business travel will likely see larger effects than others.

For manufacturing, this is the second hit in short order. Manufacturing has already felt the pain from President Donald Trump’s erratic, Wall Street-friendly trade wars, and additional disruptions from factory closures overseas make it harder to get supplies. U.S. factories may face production challenges too as the virus spread.

By comparison, the SARS epidemic in early 2003 particularly hurt the airline industry that had already been disproportionately affected by the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Manufacturing, however, accounts for a larger share of the economy than air travel and is regionally more concentrated. Of course, supply chain disruptions in manufacturing compound worries about the downturn in tourism, which has large effects on key tourist destinations such as Miami.

With states and localities in these regions already hurting, their financial capacity to respond will be limited. In short, the fallout from the virus could thus make a bad situation worse.

All levels of government need to get ahead of the COVID-19 crisis immediately. States and localities should work with federal government to maximize a coordinated response, but they should not be afraid to act proactively through legislative action, executive order, partnering with business, and otherwise. The first order of business must to stop the pandemic, but the economic response should be timely and robust. Economic tools can also play a critical role in helping to stop the pandemic. Here are specific ideas that can help.

Enable workers to protect themselves and their communities

First, economies are better protected when the public health impacts are minimized and workers continue to receive pay if work is disrupted. That can be most immediately assisted on the economic policy side by ensuring that workers do not have to show up for work when they are sick or think they are exposed to a contagious illness without losing a paycheck. More than 1 in 4 private sector workers, as of 2019, had no paid sick leave, and low-income, service-sector, and Latinx workers are least likely to have access. States and localities should immediately implement job protected paid sick leave for all workers, including additional days available immediately in the case of a declared public health emergency. Paid sick leave, where it has been implemented in states such as California, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, as well as more than a dozen cities nationwide, has proven to work. It should be mandated for all employers. Targeted emergency support may be appropriate for smaller businesses, with a more comprehensive state and federal policy following up thereafter.

To ensure that these provisions are fully deployed among economically precarious populations—many of whom may not enjoy stable schedules or reliable work—states and localities should partner with organizations, such as worker organizations, that have day-to-day contact with workers and vulnerable populations. Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles are already pioneering this model through grants and are proving it can better enforce leave protections and empower workers to stand up for their rights—which is proving to be more important than ever.

Additionally, states should provide short-term subsidization of broadband and internet access as well as partnering with telecomm providers to extend emergency service and cost reductions. Government contractors that normally must work onsite should be permitted to work remotely. Further workforce adaptation may be necessary as transportation patterns are impacts.

States also have significant roles to play in expanding health coverage as well as important aspects of the social safety net. New York, for example, has already used its authority to waive cost-sharing for COVID-19 testing. In addition to ensuring wide and fast coverage, states and localities should be working quickly to enable affected persons to apply online or over the telephone and receive benefits—without job search requirements—until the public health crisis subsides. The federal government should be doing the same and providing maximum support in these areas.

Help workers and small businesses weather the storm

Second, states and localities can help ensure workers and local businesses have the economic security they need. This may include emergency supports for workers through state unemployment insurance (UI) programs; emergency housing supports for renters; and support for food security programs, including flexibility to allow needy families to prepare for quarantines and afford other bills.

Many state UI programs are in need of reform and updating. At a minimum, states should follow the lead of states such as California and Washington where workers who are quarantined, who are caring for others, or whose job site is shut down can secure coverage and are not subject to unworkable requirements in these circumstances, such as job search reviews. Shared work and partial work programs can also help workers stay partially on the job and small businesses retain valuable staff. Deferring the collection of certain taxes, similar to what is permitted following a natural disaster, can be helpful for impacted small businesses.

The federal government has a significant role to play by here—not only by supporting state and local finances but also by updating automatic stabilizers, including UI, and securing the federal safety net for the risks COVID-19 poses. Far too many working families cannot afford a $400 emergency. Assistance may need to cover emergency expansion of housing supports, support for food security programs, and continued support for unemployment insurance. Securing the continued flow of the basics to families is essential.

Extend credit in creative ways

The economy and working families are not well-served by a vicious cycle of small business failure, empty shops and restaurants on Main Street, and job losses. Instead, states and localities should work to extend credit creatively to small businesses in order to help them get through expected rough patches. If those periods are short, then ordinary credit extensions should be sufficient. But if those periods become longer and more pronounced, loan payments may need to be deferred and some loans may even need to be written off to avoid a significant debt overhang in the local economy. That will require creative programs targeted at this disaster.

Congress recently appropriated emergency funds to support the Small Business Association’s provision of disaster assistance loans, but these loans require the governor to declare an emergency and the Trump administration to approve it. Moreover, the scale is likely too small.

One of the more flexible tools available are state small-business lending programs. States should expand their deployment and work with local financial institutions—in particular, mission-driven community development financial institutions (CDFIs) that often serve minority communities, rural America, and other specialized borrower communities—to design a set of emergency loan guarantees, deferred repayment programs, and other creative solutions to meet the specific needs of different businesses. These may need to be adjusted further depending on the severity of economic impact, so ensuring that modification is possible up front would help avoid some of the challenges of the 2008 financial crisis.

The State Small Business Credit Initiative was a Treasury Department program created after the 2008 financial crisis that directly supported state small-business lending programs in a flexible manner. It should be reauthorized and expanded to help during this sensitive period. Similarly, Congress should appropriate additional funds for the Treasury Department to support for the capital base of CDFIs, which will enable them to make additional loans. Disaster emergency responses may also be appropriate in certain circumstances.

Federal actions to secure the financial system and delay mortgage payments may be needed as well, if Italy and the United Kingdom are any guide. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) has explicitly raised this concern with national banks.

States and localities should enforce fair and open markets

It will be no easy feat to ensure open and fair markets in an economic crisis of this potential magnitude. Even as the federal government has national responsibility for critical infrastructure, international trade, and fair business practices, states have tools as well. For example, to combat the price gouging that is already showing up, state attorneys general have—and are using—business conduct and antitrust laws. These investigations should not refrain, once the public health crisis subsides, from also considering the underlying market-structure dynamics that are driving growing monopoly power in many markets.

States and local officials also have important roles to play in countering discrimination. Simply showing up at local facilities unfairly harmed by irrational fears—and even racism—is the first step. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) did just this in San Francisco’s Chinatown recently, which did not have any known cases at the time. However, stronger action may be necessary, especially over time as social distancing may be needed more broadly. In particular, officials should make it known that they are monitoring the situation carefully and are prepared to respond to any instances of credit or other access to the market being impaired on the basis of race, national origin, and the like.

States should also deploy information sharing mechanisms among themselves and the federal government to identify supply chain gaps. The federal government should act quickly to fill those, either through procurement tools already in place or through the creation of new supply chains using lending authorities such as the Defense Production Act, which provides loan guarantees to support critical infrastructure and homeland security needs. State attorneys general and treasurers can also act to hold larger companies accountable, such as through investigations into their corporate securities disclosure and accounting around supply-chain risks; worker policies around collective bargaining rights and paid sick leave; and more.

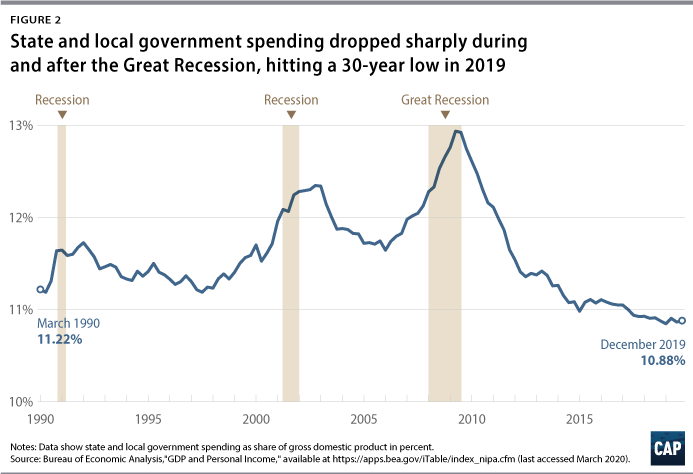

Be prepared to pick up the pieces and avoid the mistakes of the past

Once the crisis is over, it may take time for the economy to heal. State and local governments can avoid repeating the mistakes of the 2008 financial crisis by doing everything in their power to avoid cutting their budgets should revenues decline. In the 2008 global financial crisis and Great Recession, state and local revenues were hit hard. Insufficient federal fiscal support meant the impacts were severe and longer lasting than they should have been. State and local government layoffs proved to be an important driver of sustained and negative employment shocks, and reductions in services were harmful as well. Both could have been avoided had state and local governments been able to retain those workers or even expand its payrolls and support local businesses through various programs.

Yet state finances are far more constrained than the federal finances. State balanced budget requirements, as well as economic borrowing capacity limits, mean they cannot backfill revenues with borrowing—which is the economically responsible thing for government to do in an economic downturn or public crisis. Absent a rainy day fund or taking immediate action to remove balanced budget rules, state and local governments may have no choice but to immediately constrain spending.

Congress, in its supplemental appropriations, has provided $8.3 billion to address COVID-19 overall and specifically $1.05 billion to support state and local finances. But matching Singapore, for example, on a per capital basis would require $300 billion to $400 billion of direct COVID-19 response (not broader stimulus) and $40 billion to $50 billion for states and localities. Similarly, in 2009 alone, states suffered a collective $110 billion budget gap. More may well be needed for states and localities. The Trump administration’s recently suggested fiscal stimulus package—should it remain focused on a payroll tax cut for employees and employers—unfortunately is skewed in favor of upper-income earners and large corporations.

Moreover, it may be the case that infrastructure spending is called upon at some point to boost the economy—most likely as a rescue measure as the public health concerns subside. As the implementing agencies for transportation spending, states have an important role to play in ensuring that infrastructure spending leaves positive economic and social impacts and avoids social, economic, and environmental harms that present a drag on the economy and require costly fixes.

Conclusion

This only scratches the surface of the economic disruption that COVID-19 may unleash. Trump’s ongoing failure to respond effectively means that state and local officials are making tough, frontlines decisions about how to protect their residents every single day with insufficient support from the federal government. Giving communities the economic security they need to combat this public health emergency is a modest contribution that economic policy can make.

Andy Green is managing director of Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress.

The author wishes to acknowledge the support of a wide range of policy teams at CAP and particular assistance by economists Christian Weller and Michael Madowitz.

To find the latest CAP resources on the coronavirus, visit our coronavirus resource page.