The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases its monthly report with October’s jobs numbers on Friday, the day after Latina Equal Pay Day. Latinas—those of Hispanic origin in the Current Population Survey—experience one of the largest gender wage gaps among all women, earning less, on average, than white; black; Asian; Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian; and American Indian or Alaska Native women. While white, non-Hispanic women who work full-time, year-round make around 79 percent of the annual earnings of white men who work full-time, year-round, Latinas working full-time, year-round make only 54 percent of white men’s annual earnings. This means that while Equal Pay Day for women overall—the date until which women need to work through 2017 to earn as much as men did in 2016 alone—fell on April 4, 2017, Latinas must work months longer to catch up. This earnings gap can have dire consequences, especially when compounded by other obstacles Latinas face in the labor market.

Latinas make up 7.2 percent of the total U.S. workforce and are expected to make up 8.5 percent of the workforce by 2024. Although Latinas comprise a considerable percentage of the workforce, they face formidable structural barriers to entry and success in the labor market. These structural challenges mean that Latinas have lower employment rates; experience higher unemployment rates; and are more likely to work in lower paying occupations than white workers and Hispanic men. The combination of these factors means that Latinas and their families may encounter more severe difficulties in achieving economic security and social mobility. Equal pay for Latinas is especially important for family income, as almost 60 percent of Latina mothers are the primary, sole, or co-breadwinners for their families. All of these factors, combined with the low levels of wealth that Latino families hold, result in serious economic insecurity for those households.

Greater attention to economic outcomes for Latinas and other historically disadvantaged groups should inform and guide national monetary and economic policy. While some have argued that the economy has reached full employment, indicating there is little room for growth, the employment and unemployment rates of people of color tell a different story. The unemployment rate for African American men, for example, is almost twice the national rate. When one group of workers is consistently left behind on multiple metrics of economic opportunity, their status is an indicator that there is still room to tighten the labor market and ensure equitable access to opportunity. A tight labor market where there is increased job creation disproportionately helps those with the highest barriers and obstacles in the labor market, such as people of color. In addition, other barriers can reduce employment opportunities such as having a criminal record or a disability. A stable interest rate could help these groups achieve greater labor market successes by lowering unemployment rates and raising wages. The Federal Reserve has already raised rates twice in 2017, and markets expect that the Federal Reserve will raise rates again in December. A raise in interest rates too early could halt progress in lowering unemployment for marginalized communities.

Median wage

Latinas make significantly less money than most workers from other racial and ethnic groups. For example, the figure below presents the earnings ratio for white and Hispanic women ages 25 to 54—also known as prime-age workers. This analysis focuses on prime-age workers because they are the driving force of the economy; although, study of the gender wage gap at all ages can provide different and important insights. In 2016, prime-age Hispanic women made 57 percent, just more than half, of what white men made in the same year, while prime-age white women made 80 percent of what white men made.

Occupational segregation

A significant cause of the wage gap for Latinas when compared to white, non-Hispanic women and men is the fact that Latinas tend to work in lower paying occupations. The figure below displays the top 10 occupations for Hispanic women and their corresponding median annual wages. These median wages range from $18,000 to $40,000. For comparison, the median wages for white men’s top 10 occupations range from $28,000 to $145,000.*

Unemployment

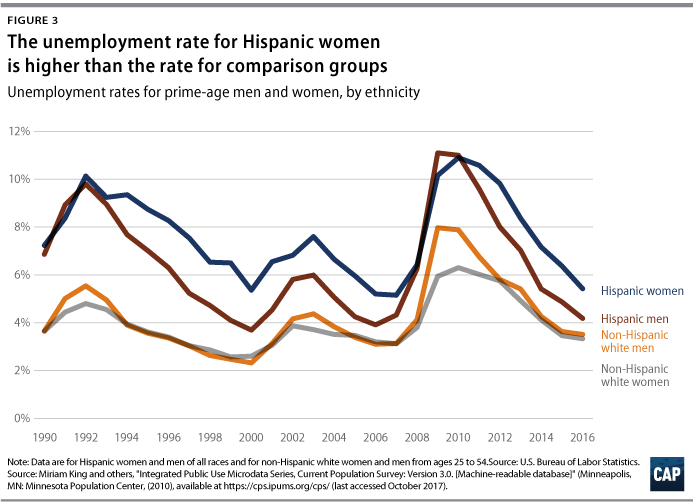

In recent history, women have had slightly lower or equal unemployment rates to men; however, this trend is reversed for Hispanic women. Hispanic women have higher unemployment rates than Hispanic men, while the unemployment rates of white women and men are very similar.

Employment-to-population ratio

Hispanic women have a much lower employment-to-population ratio (employment rate) than Hispanic men and white women and men. The employment-to-population ratio is the share of the population that is employed. Although Hispanic men and white men have almost identical employment rates, there is a more than 20 percentage point gap in the employment rates between white women and Hispanic women. More research is needed to understand Latina’s low employment rate and to answer questions such as whether it could be due to a higher likelihood of informal employment that wouldn’t be recorded in government employment data collection. Latina workers may also be less likely to respond to government surveys such as the census.

Overall economy

Overall, the economy is growing and unemployment is at prerecession levels. However, Figure 5 indicates that the employment rate remains below prerecession levels, meaning that a larger percentage of people fall outside the labor market now than in 2006. This likely indicates that many people have exited the labor market due to long-term unemployment and have not yet re-entered. Additionally, although the unemployment rate has returned to prerecession levels, certain demographics, such as youth and people of color, still face extremely high levels of unemployment and underemployment. The data presented above on the labor market experiences of Latinas are a clear illustration that more work is needed to create a healthy labor market that engages all workers.

Conclusion

Comparatively lower pay and worse labor market outcomes compound to put Latinas and their families in an especially economically precarious position. The structural disadvantages that Latinas face can also be a drag on the entire economy, as these workers are not able to achieve their full potential. Policymakers and economists need to make sure to consider the challenges of Latinas and other populations that face high labor market barriers when evaluating the health of the labor market and implementing policies that affect it.

Annie McGrew is a special assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Kate Bahn is an economist at the Center.

*Authors’ note: White men’s top occupations were calculated using CPS data for the years 2011 to 2016, and their respective wages were calculated using CPS data from 2016. The top 10 occupations for men in decreasing order were “Managers, all other,” “Driver/sales workers and truck drivers,” “First-line supervisors/managers of retail sales workers,” “Retail salespersons,” “Chief executives,” “Laborers and freight, stock, and material movers, hand,” “Carpenters,” “Construction laborers,” “Janitors and building cleaners,” and “Sales representatives, wholesale and manufacturing.”