The emails started in late 2009 or early 2010 – she can’t remember exactly, because it was only a few months later that they grew disturbing and she started documenting things. At first, she felt bad for him [Jarrod Ramos], so she shared some personal information and offered advice.“But when it seemed to me that it was turning into something that gave me a bad feeling in the pit of my stomach, that he seems to think there’s some sort of relationship here that does not exist … I tried to slowly back away from it, and he just started getting angry and vulgar to the point I had to tell him to stop,” she [the victim] told the judge. “And he was not OK with that. He would send me things and basically tell me, ‘You’re going to need restraining order now.’ ‘You can’t make me stop. I know all these things about you.’ ‘I’m going to tell everyone about your life.’ ” …

Later that month, the woman was suddenly put on probation at the bank where she worked. She said a supervisor told her it was because of an email from Ramos and a follow-up phone call in which he advised them to fire her. She said she was laid off in September and believes, but can’t prove, it was because of Ramos. She’s since gotten another job.

When she learned what Ramos had done, she called police. He stopped contacting her for a while and started counseling in November. Still, the silence was not comforting.

“That just left me to feel like he was stewing,” she said. “For all the time he was silent, he’s collecting things about me. And then comes back at me, like, 10 times worse than he had before.”

The messages resumed in January, referring to friends’ Facebook profiles and postings about her and about Ramos himself. … He told her she was afraid to let a man get close to her and discussed her family, friends, job and Rotary Club involvement – all information gleaned from the Internet.

In January, the victim went to court to get a peace order and file charges. Finally, he stopped for good.

The excerpt is from an article in the Capital Gazette newspaper that was included in court documents pertaining to a defamation lawsuit filed by Ramos against the paper.1

On June 28, 2018, Jarrod Ramos entered the Capital Gazette newsroom in Annapolis, Maryland, armed with a shotgun and harboring a long-standing grievance against the newspaper for its reporting on the harassment case against him. He shot and killed five people and wounded several others.2

In the wake of a high-profile mass shooting, there is often a collective instinct to try to ferret out something from the shooter’s past that should have served as a warning—some sign that should have alerted family, friends, or law enforcement to the potential risk posed by this person and, in turn, caused someone to intervene. As with the Capital Gazette shooting, these post hoc reviews increasingly reveal one commonality in many shooters’ pasts: violent misogyny or abuse of women.3

The link between domestic violence and gun violence is by now well-established. From 2004 to 2015, 6,313 women were murdered by an intimate partner who used a gun.4 The presence of a gun in a household that has a history of domestic violence increases the chance that a woman will be murdered by 500 percent.5 There is also a significant connection between domestic violence and mass shootings. An analysis by the advocacy organization Everytown for Gun Safety found that, of all the mass shootings—incidents in which a single shooter killed four or more people—occurring between January 2009 and December 2016, 54 percent were related to family or domestic violence.6 The National Domestic Violence Hotline, a national resource for victims of domestic violence, reported that, in 2017, there was a 74 percent increase in calls reporting that firearms were involved in the reported abuse.7

One type of abusive behavior toward women that serves as a significant risk factor for future violence is stalking—persistent threatening behavior similar to Ramos’ conduct described in the opening passage above.8 Despite this known risk, there remain serious gaps in federal and state law that allow convicted stalkers to continue to have easy access to firearms, leaving both the proximate victims of this abuse and the community at large at risk.

Stalking

Stalking is generally defined as “a course of conduct directed at a specific person that involves repeated (two or more occasions) visual or physical proximity, nonconsensual communication, or verbal, written, or implied threats, or a combination thereof, that would cause a reasonable person fear.”9 Stalking often includes unwanted communication, including phone calls, text messages, emails, and social media messages; following or watching the victim from a distance; and unexpectedly appearing at locations where the victim is known to be present, such as home, school, or work.10 Stalking poses significant concerns for the safety of a victim, as this is an ongoing course-of-conduct crime that tends to escalate in frequency and severity. Stalking also has a devastating psychological impact on victims, even when the threatening conduct has stopped. Victims of stalking report experiencing elevated rates of traumatic stress, excessive fear, and anxiety.11 These effects have a lasting impact on a victim’s quality of life and can lead to disruptions in social interactions and employment.12

Stalking is also a risk factor for future violence.13 One study of female murder victims in 10 U.S. cities found that 76 percent of women who were murdered and 85 percent of women who survived a murder attempt by a current or former intimate partner experienced stalking in the year preceding the murder or murder attempt, respectively.14 Another study found that 81 percent of women stalked by a current or former intimate partner were also physically abused by that person.15

According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), a project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 6 women experience stalking during their lifetime, compared with 1 in 19 men.16 Rates of stalking were highest among Native American women and women who self-identified as multiracial, with more than a quarter of women in each group reporting stalking at some point in their lifetimes.17 Moreover, stalking is most prevalent in intimate partner relationships: The NISVS found that 61.5 percent of stalkers were current or former intimate partners, while 26 percent of stalkers were acquaintances, and 15 percent were strangers.18

Criminalizing stalking and disarming stalkers

Stalking is treated as a serious crime under both federal and state law. While the particular elements of this crime vary from state to state, every state has enacted laws criminalizing stalking, and many have made it a felony-level offense for the most severe cases of abuse.19 In addition, at least 37 states have enacted misdemeanor-level stalking crimes in order to cover the full range of this dangerous and threatening conduct.20 The fact that some states have made stalking a misdemeanor offense should not discount the seriousness of this crime. Stalking is often the first step in an escalating course of conduct, and many courts and prosecutors will allow a defendant to plead to a misdemeanor-level charge in order to expedite proceedings, especially if the victim does not wish to participate in an extended criminal proceeding.

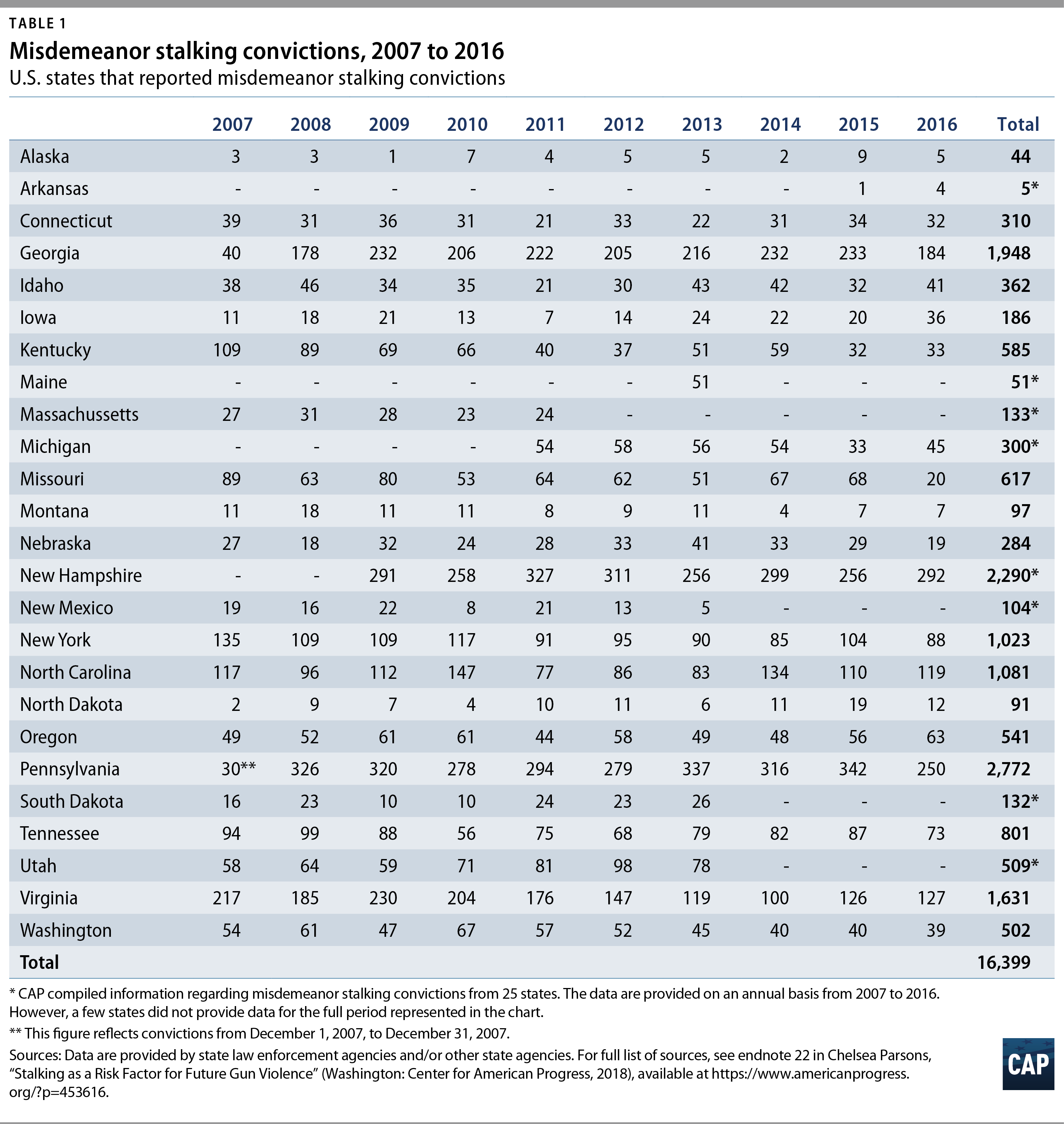

When an individual is convicted of a felony-level stalking crime, that conviction carries the collateral consequence of rendering the person ineligible for gun possession under federal and state law.21 However, individuals convicted of misdemeanor stalking are not covered by the federal law and remain free to buy and possess guns. The Center for American Progress obtained data from 25 states and found that, from 2007 to 2016, 16,399 individuals were convicted of misdemeanor stalking crimes.22 This is a significant undercount, as it represents conviction data from only a portion of states that have a misdemeanor stalking crime on their books, and many of the states that did provide data failed to provide them for every year in this 10-year time span. However, these data demonstrate the significant number of individuals who have engaged in criminal conduct that is a risk factor for future violence—particularly against the previous victims of their abuse—and who continue to have access to guns under federal law.

Where federal law has missed the mark, a number of states have stepped in to fill this gap. According to a review of state laws by Everytown for Gun Safety, 19 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws prohibiting individuals from buying or possessing guns following any stalking conviction, either felony or misdemeanor.23

Federal and state policymakers have begun to act to protect victims of stalking from future gun violence. In both houses of Congress, legislation has been introduced to address this gap in the law and to ensure that all convicted stalkers, regardless of whether they were convicted of a felony or misdemeanor, are prohibited from gun possession under federal law.24 State legislatures continue to take action to disarm stalkers; in fact, during the 2018 legislative session, legislators in four states introduced bills to this effect.25

However, another loophole in federal law puts stalking victims at risk for future gun violence, even when states have enacted laws to prohibit convicted stalkers from gun possession. Under federal law, licensed gun dealers are required to conduct a background check before transferring a gun; however, private individuals are free to sell guns without conducting a background check. As a consequence, a person who is prohibited from buying guns and unable to pass a background check can evade the law by buying a gun from a private seller at a gun show, online, or in any other venue without a background check and with no questions asked. To date, 20 states and the District of Columbia have acted to close this glaring loophole by requiring a background check for all handgun sales. Yet Congress has failed to follow suit and act to make this sensible requirement apply nationwide.26

Finally, there are other gaps in the federal law related to domestic violence that deserve attention and action as well. While, under current federal law, some domestic abusers are barred from gun possession as a result of their conduct—those convicted of misdemeanor crimes of domestic violence or subject to a domestic violence restraining order—this law is not comprehensive and leaves many victims of abuse vulnerable to lethal violence.27 Notably, the federal law does not cover abusers convicted of violence against a dating partner rather than against a current or former spouse. The federal firearm ownership prohibition also does not apply when a court issues a temporary restraining order against an abuser—the period of the most heightened risk for domestic abuse survivors.28

Conclusion

“I know he can’t come and get me today, but I have been tormented and traumatized and terrorized for so long that it has, I think, changed the fiber of my being.”29

— Ramos’ stalking victim, in an interview after the Capital Gazette shooting

A history of misogyny and violence against women is a known risk factor for future gun violence, particularly when that conduct has risen to the level of a criminal conviction. Policymakers need to take this risk seriously and do what is necessary to ensure that convicted stalkers cannot slip through cracks in the law and have continued easy access to guns.

Chelsea Parsons is the vice president of Gun Violence Prevention at the Center for American Progress.

The author wishes to thank Eugenio Weigend and Tori Saylor for data collection and research assistance for this issue brief.