The tax bills that the House and Senate have passed and are now seeking to reconcile would add nearly $1.5 trillion to federal deficits over the next decade, according to the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). One of the ways in which the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress are rationalizing adding so much debt is by claiming that they are measuring the tax bill against a “current policy” baseline instead of the traditional “current law” baseline. But in applying a current policy baseline to the bill under the assumption that it reduces the cost, they are making a major error. The fact is that the Senate tax bill adds even more to deficits when using current policy assumptions. Under this approach, the bill’s many expiring tax cuts would be treated as if they were permanent, significantly raising their cost.

Proponents of the tax bill are justifying its massive cost by purporting to measure it against a ‘current policy’ baseline

The Treasury Department has come under heavy criticism for the one-page document it released on December 11, and deservedly so. The document claims to be an economic analysis of the Senate tax bill, but it is not an analysis at all. One aspect of the document, however, deserves even more scrutiny. It states that the Senate tax bill (without taking into account any economic growth projected to result from the tax plan) would reduce revenue by $1.5 trillion “on a current law basis and approximately [$1 trillion] on a current policy basis.” This implies that the bill costs about $500 billion less when measured against a current policy baseline.

Similarly, last week, Sen. Jeff Flake (R-AZ) justified his vote for the bill by claiming that the bill costs about $500 billion less under current policy than under current law. Even the one member of the Senate majority who voted against the tax bill, Sen. Bob Corker (TN), has incorrectly assumed that any tax overhaul will cost $500 billion less when measured against current policy.

The bill’s proponents are relying on the current policy baseline to help bridge the chasm between their assertions that the bill does not reduce the deficit and the many estimates finding that it substantially increases deficits. But these proponents are mistaken. As this column explains, the Senate bill costs more when measured using consistent current policy assumptions.

Baselines explained

The baseline is simply the level of revenues that the government is expected to collect in the absence of whatever bill Congress is considering. If the government is expected to raise $100 in revenue if no bill passes and $90 if a particular bill passes, then one can say that the bill has a “cost” of $10 in reduced revenue relative to the baseline.

Under longstanding practice, Congress’ nonpartisan scorekeeper for tax bills, the Joint Committee on Taxation, uses what is called a current law baseline. This means that in estimating how much revenue the government will collect in the future, the JCT assumes that the laws on the books will not change—for example, if a particular tax break is scheduled in law to expire after a certain year, JCT assumes that it will, in fact, expire. By contrast, under a current policy baseline, scorekeepers assume that tax breaks in effect today will stay in effect even if they are set to expire—in other words, that Congress will perpetually extend them.

Since the current policy baseline assumes that temporary tax breaks will be renewed rather than expire, the baseline level of revenues under current policy is lower than under current law.

The Senate tax bill costs even more when measured using current policy assumptions

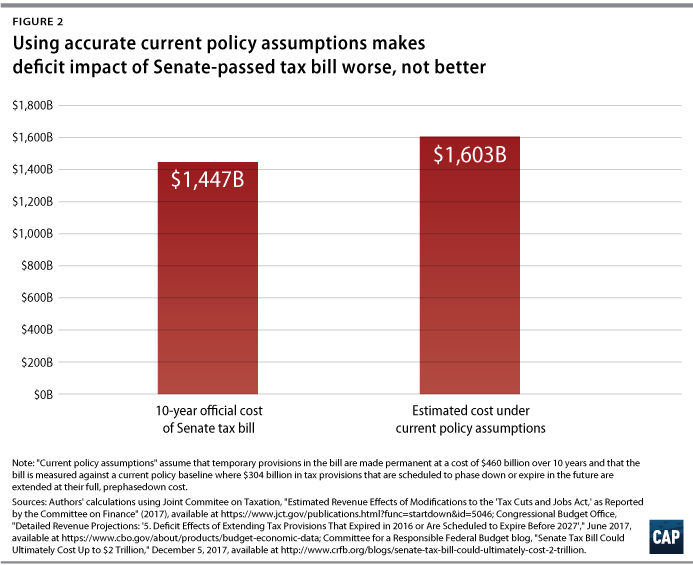

If one assumes that Congress will perpetually extend the tax provisions that are currently in effect but that are scheduled to phase out or expire at some point, then federal revenues will be $304 billion lower than under current law. In other words, the current policy baseline is $304 billion lower than the current law baseline.

In discussing the Senate tax bill, proponents of the tax bill have said that the current policy baseline is $462 billion—generously rounded to $500 billion—lower than the current law baseline because they erroneously include the cost of tax breaks that have already expired. $158 billion of temporary tax provisions known as “tax extenders” expired at the end of 2016, the result of Congress’ deliberate decision at the end of 2015 to make many provisions permanent while letting others expire. After members of Congress reached a bipartisan deal on these so-called tax extenders, Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX) stated that the “confusion ends now” over which tax cuts were temporary and which were permanent. The provisions that Congress deliberately let die included tax breaks for race horses, automotive race tracks, and other special-interest earmarks. These provisions are not current policy because they have already expired. They are expired policy.

But the bigger mistake proponents of using a current policy baseline are making is ignoring that the Senate tax bill creates a boatload of new temporary tax breaks. If the cost of the tax bill is measured against a baseline that assumes Congress will extend the temporary tax breaks that are already on the books, then scorekeepers must logically assume that Congress will also extend the temporary tax breaks it is creating in the bill. It would be inconsistent and incoherent for scorekeepers to assume that Congress will extend tax breaks it created years ago—especially those that have already expired—while also assuming that Congress will let the new tax breaks expire on schedule.

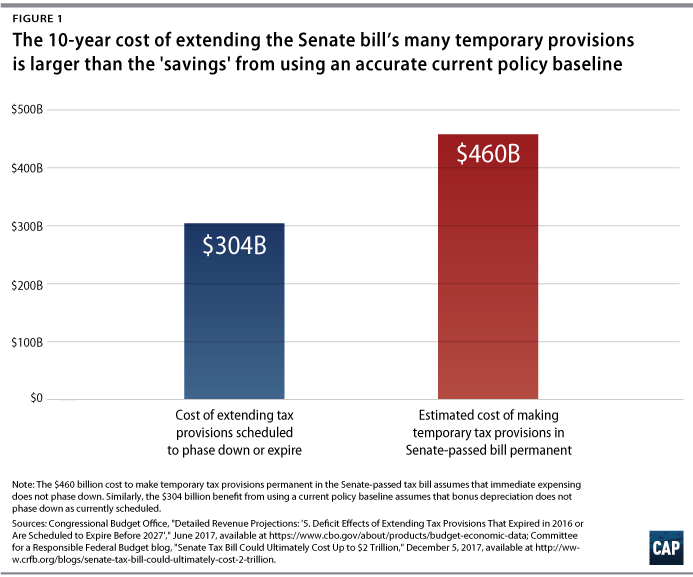

The Senate tax bill includes dozens of temporary provisions. Most notably, nearly all the bill’s changes to the individual tax code expire after 2025. Making the individual tax provisions permanent would cost up to $300 billion over the remainder of the 10-year budget window, according to estimates from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB). And of course, this would cost even more over the longer term. The bill includes temporary cuts on the corporate side as well, such as full business expensing, which is scheduled to begin to phase down after five years. According to the CRFB’s estimates, once the cost of making all the bill’s temporary cuts permanent is taken into account, the bill would cost up to $460 billion more than the cost of the bill as scored by the JCT over 10 years. The bill also includes a number of revenue-raising provisions that are not scheduled to take effect until several years in the future that would add about $125 billion to the bill’s fiscal cost if Congress ultimately prevents them from going into effect.

The bottom line is that applying current policy assumptions to the Senate bill actually raises the bill’s estimated cost. The baseline would be $304 billion lower, but the bill would bring in $460 billion less in revenue. Therefore, the bill that costs nearly $1.5 trillion relative to current law would cost approximately $1.6 trillion relative to current policy once temporary provisions are taken into account.

The revenue feedback from dynamic scoring—in other words, factoring in the macroeconomic effects that are projected to result from the bill—can only make up for a fraction of that cost. For example, the JCT found that the macroeconomic effects of the Senate bill would reduce the bill’s impact on the deficit by $408 billion. The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center estimates that the bill would cost only $186 billion less under dynamic scoring, and the Penn Wharton model estimates that dynamic scoring would reduce revenue loss by between $219 billion and $441 billion.

Conclusion

As the Center for American Progress has argued previously, Congress should measure the cost of tax bills against current law, not current policy. But if members of Congress prefer using current policy assumptions, they need to do so accurately and coherently—and if they do so, they will find that the Senate tax bill increases deficits by even more than the official current law estimates.

Seth Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Alex Rowell is a research associate for Economic Policy at the Center.