Introduction and summary

Reviving America’s strategic position in the world in the wake of President Donald Trump will require a foreign policy that both firmly embraces democratic values and systematically pushes back against authoritarian competitors such as Russia and China. The Trump presidency has already severely undercut the United States’ global standing, causing immense harm to the nation’s strategic position, credibility, and moral authority. Allies are losing faith in American leadership while illiberal regimes are growing in number, stature, and audacity. Trump’s rise reflects a pre-existing deterioration in the vitality of democratic systems, a global phenomenon which his presidency has now turned into a crisis. The damage cannot be reversed simply by electing a different president or reverting to previous foreign policy approaches. Instead, the United States must adopt bold new policies to regain the advantage in great power competition and help vulnerable democracies, including its own, resist authoritarian influence and strengthen a growing global democratic community. This report explains why a democratic values-based foreign policy is the right choice for the United States on both a strategic and moral level. It also offers specific policy recommendations as a roadmap for how the next administration could pursue a democratic values-based foreign policy.

Today, democracy is under strain in America and threatened across the globe. The spread of democratic governance, which for decades seemed all but inevitable, has stalled and now faces serious setbacks. Across the democratic world, ordinary people have lost trust in their institutions of government and delivered stunning rebukes to their political establishments. These setbacks have also emboldened authoritarian regimes. Russia, China, and other illiberal states have sought to exploit the openness of democratic societies for their geopolitical advantage and have put forward an alternative autocratic model for politics and economic development that undermines liberal democratic values.

America’s enduring security, prosperity, and strength depend on the survival and success of democracy—both at home and abroad—as well as on the resilience of institutions, rules, and norms that protect the liberal democratic values on which the United States’ global standing is built. Yet at the very moment when liberal democracy faces its greatest ideological challenge since the Cold War, President Trump has chosen to reject America’s historic role as leader of the world’s democracies. He has treated democratic allies as ideological foes and murderous dictators as respected friends and equals while stoking nativist and isolationist impulses among the American people. President Trump has also systematically denigrated democratic values and norms at home through unprecedented attacks on the press, the independent judiciary, and law enforcement, as well as political purges of civil servants.1 While U.S. democratic institutions have shown resilience in the face of his challenges, it is already clear that some of the damage Trump does will outlast his presidency. The critical question today is whether the United States after Trump will summon the resolve to lead, protect, and expand the world’s democracies or stand by and suffer the consequences as autocracy and illiberalism crack the foundations of the American-led global system.

Advancing a values-based foreign policy after Trump will inevitably invite a vigorous debate over how—or even whether—values should factor into U.S. foreign policy. Critics will likely point to America’s prior foreign policy errors and shortcomings, for example, the use of democracy promotion aims to justify misguided foreign policies such as the invasion of Iraq; the broader U.S. failure to promote democracy in the Middle East in the wake of the Arab Spring; and Cold War-era support for dictators who sided against the Soviet Union. Critics may also point to the urgency of domestic challenges relative to foreign policy ones or fear of U.S. overextension abroad to argue that a values-based foreign policy is unwise or simply not possible. This report takes these critiques seriously. However, in reflecting on the stakes for U.S. leadership, present and future, it arrives at the conclusion that an American foreign policy shorn of American values would ultimately deliver less security and prosperity at home, while making U.S. leadership in the world less sustainable and impactful.

This report asserts that an approach that embraces America’s core democratic values will allow the United States to compete more effectively with authoritarian powers such as China and Russia and will deliver better results for the country in the long haul. To address setbacks abroad, the United States will need to pursue a new foreign policy that systematically puts liberal democratic values at the center of its engagement with the world. This will require more than just lip service. It will entail a meaningful, sustained shift in how the United States conducts its foreign relations, launched with quick and decisive action and sustained with persistence and strategic vision.

A democratic values-based foreign policy strategy is rooted in faith in democratic self-government, not just as being better than all the alternatives but also as a value in and of itself. Such a foreign policy will also advance U.S. national interests. America’s presence as a prosperous, multi-ethnic, free democratic society poses a challenge to autocrats through the model it sets. Instead of taking this power for granted, it is time for America to cultivate it.

At the heart of such an effort should be a realignment of American foreign policy to meet the challenge posed by resurgent illiberalism. This can be done by forging stronger cooperation among democratic states, including in the defense of democracies under assault and the expansion of the global democratic space. In both the short- and long-term, the United States will need to take the following steps:

- Restore democratic values and norms at home.

- Work with democratic allies to design and implement a counter-authoritarian playbook to push back against the encroachment on and abuse of the open systems of democratic states.

- Build stronger international networks of democracies to create a global democratic bulwark.

- Privilege U.S. relationships with democracies, and reflect this in U.S. policy decisions and spending.

- Strengthen international support mechanisms for populations nonviolently mobilizing for democracy around the world, while more systematically pressuring countries to uphold human rights and adhere to international law.

Reorienting U.S. foreign policy toward a values-based approach will require policymakers to take the long view, recognize the intrinsic strength of democratic governance, and acknowledge that the best way to advance democracy worldwide is through the example set by successful democracies. Critically, it will also require U.S. leaders to heed the lessons of history by recognizing that the most effective way to promote and sustain democracy is supporting and encouraging democratic institutions and movements, rather than employing coercive measures. The United States has numerous tools to vigorously defend its values and advance democracy without seeking to impose it using force.

Some may fear that a values-based foreign policy would come at the expense of traditional U.S. interests. But that critique misdiagnoses and underestimates the geopolitical challenge to U.S. interests that a rising illiberal tide presents. American interests will be far more difficult to secure if liberal democracy is supplanted as the pre-eminent and most sought-after political system. There will inevitably be times when U.S. interests will necessitate partnering with nondemocratic regimes. Still, a principled but pragmatic approach can do both: cooperate selectively with such regimes on matters of vital national interest while also recognizing that the greatest strategic gains to U.S. security and prosperity will rest on the success of other democracies and that America’s staying power and strategic resilience will depend on investing in them.

The challenge: A democracy crisis at home and abroad

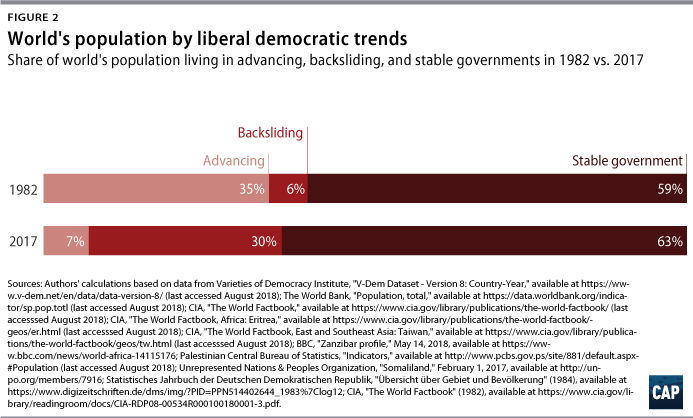

For most of the past 50 years, the world has witnessed the dramatic spread of democratic governance throughout the globe. Between 1970 and 2010, the number of democratic states nearly tripled, with transitions to democracy stretching from the southern cone of South America to West Africa, Southeast Asia, and the former Soviet bloc.2 By 2000, more than half the world’s population lived under a democratic government for the first time in recorded history.3 This democratic wave brought a host of political and social rights to hundreds of millions of people and coincided with a historic decline in the incidence of interstate wars.4

The ascendance of democracy globally and the emergence of an increasingly robust set of international rules and institutions fostered a prevailing assumption that a more democratic world was here to stay: Democratic states would prosper and more autocratic states would transition to democracy. But this optimism about democracy has waned due to a number of varying and reinforcing trends.

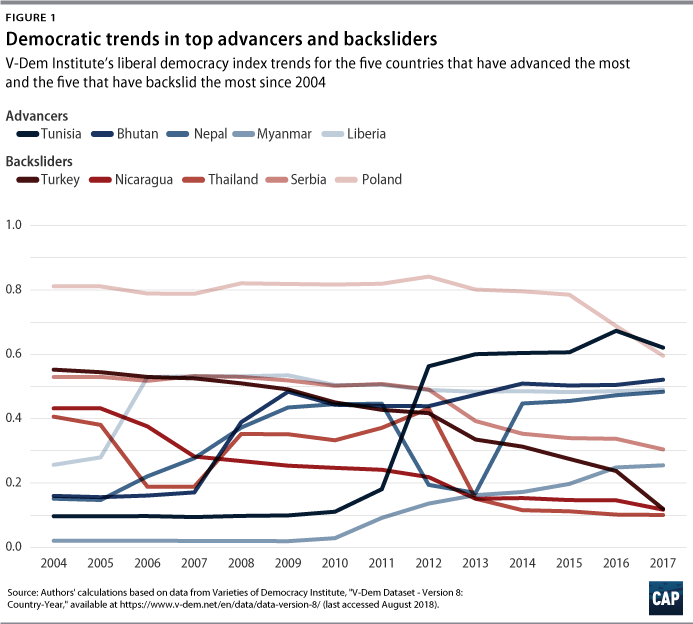

First, democracies have experienced setbacks. Many countries once held up as examples of democratic progress—such as Poland, Turkey, and Venezuela—have experienced a deterioration in rule of law and electoral competitiveness.5 In other countries, such as Thailand and Egypt, democratically elected governments were overthrown by force. Meanwhile, across the Middle East, the democratic promise of the Arab Spring faltered in the face of violent repression. During this same period, illiberal and insular populist movements became resurgent in many established democracies, weakening international cooperation among democratic states and imperiling many of the achievements of the postwar era. These movements occurred most notably in the European Union, where a Center for American Progress and American Enterprise Institute study found that “in the past decade, such parties have moved from the margins of Europe’s political landscape to its core.”6

A key feature of this illiberal resurgence has been elected leaders’ use of strongman tactics to undermine democratic institutions and norms. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has gained increasing control over the political, economic, and military aspects of the Turkish state.7 In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has used xenophobic rhetoric and crony capitalism to erode political checks and balances and consolidate power.8 Poland’s current leaders and others have followed Orbán’s playbook, attacking the independence of the country’s media and judiciary and campaigning on an exclusionary vison of Polish society.9 President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, meanwhile, has flaunted his disdain for the rule of law and human rights as he pursues a campaign of mass violence against drug users and dealers, which has included state sponsorship of extrajudicial killings.10 In all of these cases, attacks on democratic institutions and norms have been carried out by democratically elected leaders themselves.11

Even in the United States, President Donald Trump is showing signs of authoritarian envy, regularly criticizing the media, the judiciary, and law enforcement, while openly admiring some of the world’s most brutal dictators. As Trump said of Kim Jong Un, who rules over a totalitarian dictatorship where people are thrown into labor camps for criticizing the government: “He’s the head of the country, and I mean he’s the strong head. … Don’t let anyone think anything different. He speaks and his people sit up at attention. I want my people to do the same.”12

These trends do not mean in any way that democracy is a lost cause or that the global tilt toward illiberalism is irreversible. Demand for democratic change and greater civil and political rights remains a potent force that transcends culture and geography, as recent events in countries as diverse as Burkina Faso, Armenia, and Malaysia illustrate.13 But these positive developments do not negate the democratic backsliding that has occurred elsewhere. Across the world, democracy faces an uncertain future.

Second, confidence in democratic politics has waned, even in states with long traditions of representative government. In the past two decades, democracies have struggled to deliver economic results for their people. Even democracies that have experienced rapid growth have too often seen it disproportionally benefit small elites or specific regions, while causing significant disruption elsewhere in society.14 The Great Recession of 2008 and years of painfully slow recovery helped fuel a sharp decline in trust in government institutions across the democratic world.15 Stagnation and deepening inequality, coupled with demographic change and political dysfunction, have created fertile ground for distrust, division, and demagoguery that illiberal populist parties have exploited. These groups draw on xenophobic and racist messaging but also resentment at economic stagnation and elite capture of supposedly democratic institutions. In some cases, they have also made both subtle and overt appeals to authoritarian modes of governance.16

The United States has not been immune to this democratic malaise. Americans today distrust their government in greater numbers than at any point in modern U.S. history, including the height of the Vietnam War and during the Watergate scandal.17 Two of the most significant drivers of distrust have been the rise of unfettered special interest spending to distort U.S. politics and the political paralysis that has arisen from the growth of counter-majoritarian practices such as gerrymandering and abuse of the legislative filibuster.18 These problems have fed a widespread perception that the U.S. political system no longer represents the interests of ordinary Americans nor does it address grave challenges such as inequality, racial injustice, and opioid addiction. Such failures, compounded by foreign policy failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, have contributed to a profound loss of faith in American institutions that Donald Trump effectively channeled in his bid for the presidency.

Third, illiberal and authoritarian regimes have sought to encourage and exploit the crisis of confidence in democratic states in order to weaken them from within, assert the superiority of their own models, and attack the foundations of the post-Cold War geopolitical order. Of these revisionist states, Russia has been the most overt and aggressive in its challenge to liberal democracy. Despite a stagnating economy and shrinking population, Moscow has launched ambitious measures to reestablish a sphere of influence in nearby countries, fueled right- and left-wing populist movements across Europe and North America, and sowed confusion and discord among the democratic citizenries of EU states and NATO members, including America.19 The tools it has deployed in this campaign include disinformation operations using both traditional and social media; targeted use of corruption to cultivate political proxies; cyberespionage aimed at influencing electoral outcomes; covert funding of insurgent political movements; and exploitation of neighbors’ energy insecurity.20 Together, Russian tactics constitute a new authoritarian playbook to which the United States and other democratic powers have yet to develop an effective response.21

If Russia has been the boldest challenger, the most serious long-term external threat to democratic governance comes from China. Beijing has been—and will almost certainly remain—an essential partner of the United States in solving major global challenges, from climate change to nonproliferation. But as China amasses power, too often it has put its newfound capabilities and immense resources behind a model of political and economic development and interstate cooperation that neither requires nor encourages liberal democratic values.22 In fact, China’s full-throated assertion of narrow national interests in areas such as internet governance, free speech, trade, and human rights often actively undermines democratic values.23 China has also sought to use economic coercion to undermine U.S. security alliances and partnerships in the Asia-Pacific region and erode cohesion among EU member states.24 Meanwhile, Beijing has used its economic and growing military might to immunize itself from the consequences of flouting long-standing international principles such as freedom of navigation.25 Tragically, these developments coincide with President Trump’s abandonment of America’s commitments to global leadership, including the Iran nuclear deal, the Paris climate agreement, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Fourth, the institutions, rules, and norms that underpin the liberal international order have not lived up to expectations, providing space for illiberal and undemocratic states to seize the advantage. The global and regional organizations established since World War II were built to protect and encourage liberal values, including universal human rights and rules-based international conduct. But these institutions largely reflect the world of 1945 and have not been adequately updated to recognize the massive shifts in global economic and political power. Today, many of these institutions are losing the capacity to perform their basic missions because of inherent structural flaws, outdated mechanisms, and deliberate efforts by world powers to undermine or circumvent them. The U.N. Security Council is rarely able to meaningfully respond to gross abuses of human rights or even outright aggression.26 The United States and other democracies face growing challenges in upholding international rules or solving big problems such as chemical weapons use in Syria, ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, China’s violations of international law in the South China Sea, and Russia’s use of gray-zone tactics in Ukraine. The World Trade Organization has likewise struggled to address abuses of its trade rules by states such as China.27 Without more effective and coordinated efforts to push back against these abuses and transgressions, authoritarian governments will continue to probe the boundaries of international rules and norms in ways contrary to both U.S. values and interests.

Fifth, economic globalization has exposed autocratic systems to democratic values, but it has also exposed democratic systems to autocratic influence. As the globalization of the world economy accelerated in the 1990s, experts assumed that integration would result in a more liberal future.28 Authoritarian states, once closed, would be opened up and exposed to the practices and values of liberal democratic states. Gradually, these autocratic states would begin to take on more liberal characteristics, accelerating the trend toward greater democratization. But globalization has proved to be a two-way street. Liberal states have also been exposed to the influence of authoritarian states. Foreign investment from autocratic regimes has served as a vehicle to influence their recipients, most notably in the form of Russian cultivation of political actors across Eastern Europe.29 The corrupt and uncompetitive inducements of autocrats have at times proved a more attractive path than more transparent business and investment practices favored by democracies.30 The immense wealth concentration in autocratic states—and liberal ones as well—has spawned a complex transnational network of illicit finance that has distorted both developed and developing economies.31

Lastly, the Trump administration is now undermining the democratic values and international rules the United States has traditionally sought to uphold. Although the challenges facing global democracy have been building for many years, they have accelerated since 2016 in part because of the policies and rhetoric of the current occupant of the Oval Office. In a remarkably short period of time, President Trump has taken dramatic steps to abandon America’s long-standing moral leadership in the world. President Trump’s first secretary of state publicly declared that the United States would not prioritize human rights.32 The Trump administration has vigorously attacked America’s democratic allies while showing an affinity for autocrats and dictators.33 On an almost daily basis, the president makes clear his disregard for many long-standing norms of American government, such as separation of personal and public interests and respect for the autonomy of the judiciary and law enforcement. While in the past American foreign policy has been prone to charges of hypocrisy—such as claiming to uphold democracy while backing autocrats—the Trump administration has abandoned any pretense of concern for democratic values. This sharp shift in America’s approach to the world under President Trump has been immensely destabilizing in ways that are only beginning to become clear.34

The answer: A democratic values-based foreign policy

Donald Trump is hardly the only skeptic of a democratic values-based foreign policy. A range of policymakers and scholars of foreign policy, including some progressives, have argued that the United States should de-prioritize the promotion of democratic values in its foreign policy. Some make the argument that the United States needs to take a more hardheaded and transactional approach to advance its security and economic interests. However, this report argues that not only are these false choices but that the United States should see democratic values as a U.S. comparative advantage—and not a weakness—in global competition. America’s liberal democratic values have been key to building, enhancing, and sustaining America’s geopolitical power. With the global backsliding of democracy and the rise of alternative authoritarian models, it is ever more urgent to rediscover the power of core American values to secure U.S. interests in the long term.

A democratic values-based foreign policy is worth pursuing for three key reasons.

First, it will advance long-term U.S. economic and security interests abroad and create a safer and more prosperous world. Compared with authoritarian regimes, democracies are less likely to go to war against each other, less likely to ally against the United States, less likely to sponsor terrorism, less likely to experience famine or produce refugees, and more likely to adopt market economies and form economic partnerships with other democracies.35 Since liberal democracies tend to share values rooted in rule of law, fair competition, and transparency, they are natural partners in promoting the stable, prosperous, open, and peaceful international environment that the United States ought to cultivate through its foreign policy.

It is true that the process of democratization can be long and uneven and can sometimes produce destabilizing and aggressive state behavior. However, mature and established democracies are more stable, peaceful, and prosperous, and more full-fledged democracies mean more economic and security benefits for the United States.36 Furthermore, the global system of democratic alliances, institutions, and norms the United States helped create and lead after World War II has improved material conditions and brought peace and prosperity to hundreds of millions of people across the world. Bolstering that democratic system and the democratic values that underpin it will ensure that future generations can also enjoy the fruits of democracy and a liberal world.

Second, this kind of foreign policy will help secure an American advantage in great power competition by advancing a compelling alternative and strengthening the global democratic bulwark. Although the challenge posed by illiberal regimes today has evolved since the Cold War, there are still lessons to be drawn from that era. One of the most significant factors in the collapse of the Soviet Union was the powerful example and contrast set by flourishing democratic societies in the United States and Europe. Today, one of America’s greatest strategic assets is its global network of democratic allies and partners. The power of that democratic network, even underutilized as it is today, stands in stark contrast to what today’s illiberal and authoritarian regimes can offer: namely, political order purchased at the cost of extreme corruption, xenophobia, oligarchy, and arbitrary use of state power. To succeed, any approach to countering the authoritarian playbook must present a compelling alternative. This means that the United States, alongside its democratic allies and partners, must demonstrate that liberal democracy represents the best path to deliver inclusive prosperity, rule of law, and a just and equal society to a country’s citizens.

Third, it is the right thing to do. For more than a century, U.S. support for global democracy promotion has rested in part on the sincere conviction that all people deserve to have a say in how they are governed and enjoy the freedoms afforded people in liberal democracies. Although the United States has at many junctures acted in ways that undermined the expansion of democracy and democratic freedoms, that failure does not make democracy promotion any less worthy a goal for U.S. foreign policy. Put simply, there is intrinsic moral value in using the immense influence and capabilities of the United States to empower ordinary people across the globe.

The way forward: A democracy-rebalance agenda for the next administration

To achieve these aims, the United States should implement a “democracy rebalance” designed to defend the existing liberal international order, motivate and empower global democracies to work together, and stem the rising tide of illiberalism. This effort would need to be more than a rhetorical shift. It would require Washington to undertake a strategic prioritization of effort to make protecting and advancing democracy a central pillar of the U.S. national security strategy. This strategic shift should be guided by the following principles:

- First, the incentives must be significant. The United States and its democratic allies must generate enough of a pull factor through economic, political, and security benefits to incentivize transitional democracies to continue along the democratic path and to help consolidate democratic gains in both new and established democracies.

- Second, there is strength in numbers. When providing incentives—and pushing back against illiberalism—the United States and its democratic partners need to lock arms to maximize effectiveness in an increasingly competitive global environment.

- Third, this must be a strategic priority that reorients and draws on all the tools of American statecraft. The focus of U.S. foreign policy often is pulled in various directions, but this democracy rebalance would require vigorous strategic prioritization.

- Fourth, democracy should not be spread through use of force. Military force should always be the last resort and only employed to address severe or acute security crises—not to advance a preferred political system. Resilient democratic governance is only possible through patient and sustained commitment to building effective democratic institutions. Military force will never be a substitute for this tried and tested approach.

- Fifth, the United States should seek to avoid acting unilaterally. Rather, it should practice humility and seek to work with and learn from countries that have pushed back successfully against the authoritarian playbook.

- Sixth, the most powerful force for global democracy will always be the aspirations of ordinary people. While it is natural for policymakers to focus on incentives and pressure points for foreign governments, the most durable and profound democratic change has historically come from grassroots, bottom-up movements. To that end, the United States and its partners should be prepared to support and defend the rights of people around the world to mobilize nonviolently in support of greater civil and political freedoms.

How should the United States define democracy?

This report considers the term democracy to encompass the consent of the governed and basic freedoms such as freedom of speech and assembly, a free press, equality before the law, free and fair elections, checks and balances, and protection of basic human rights as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, among other international agreements and conventions. But assessing which countries qualify as democratic for the purposes of U.S. foreign policy will inevitably require judgment calls. Fortunately, there are already several sets of criteria available for determining the strength of a country’s democracy, such as the Polity IV Project index and the V-Dem Institute’s Liberal Democracy Index.37 Some of these criteria are already incorporated into how the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a U.S. foreign aid agency, determines which countries are eligible to receive its assistance. Other U.S. assistance programs may wish to do the same.

Policy recommendations

Revitalizing global democracy is an immense and complex task that will take many years. But in the short term, the threat presented by opportunist authoritarian regimes urgently requires a rapid response. That is why America’s democracy rebalance needs both an immediate defensive line of effort to protect democratic values at home and around the world from creeping authoritarianism and a sustained long-term effort to expand the global democratic community and address the drivers of democratic retrenchment.

Strengthen democracy at home

American foreign policy starts at home with the strength of our own democratic model. None of the initiatives proposed in this report is likely to succeed if the United States does not embrace its own democratic values and norms and lead by example. The next administration will need to simultaneously re-establish international credibility and strengthen the democratic compact with its own citizens. For the United States to compete effectively in the global battle of ideas, it must continue to perfect its own democracy and leverage its own comparative strengths: rule of law, strong institutions, the ability to self-correct as a nation, and the innovation and perseverance of the American people. While domestic policy is not the focus of this report, the authors felt it was essential to draw the connection between the health of American democracy and the strategic impact that the United States can drive globally in the context of rising competition.

Restore democratic values and norms

The next administration will need to emphasize its adherence to democratic norms, including reaffirming and embracing the role of a free press, respecting the independence of the judiciary and law enforcement, valuing its civil servants, rejecting racial and religious antagonism, and separating the interests of the public from the private interests of those in power. A series of strong and clear measures in this direction in the early days of the next administration will be a necessary predicate to restoring American credibility abroad.

Build trust in science and facts

With the assault on science and facts by the Trump administration and its allies—removing publicly available information on climate change from government agency websites, for instance, and certain conservative media outlets pushing baseless claims—it will be imperative for the U.S. government to ensure that policy decisions are driven by data and science and that information about policies are communicated objectively and clearly.38

Address drivers of declining public trust

The next administration will need to demonstrate that it can deliver for all Americans and restore the basic compact between the governed and the governing. That means mounting an effective response to entrenched economic inequality, structural racism, gun violence, poor health outcomes, the dominance of special interests, and persistent poverty and the challenges that accompany it, including rising drug addiction. Without confronting these scourges head-on, America cannot effectively advocate for and support liberal democracy abroad.39

Ensure a free and fair democratic process

For the United States to advance democracy abroad, it is essential that its democratic processes serve as a model, not as a cautionary tale. Currently, U.S. democratic processes are plagued by gerrymandering, a campaign finance system that strongly favors wealthy private interests, and weak transparency rules that distort democratic outcomes. The next administration, in conjunction with Congress, must seek to make meaningful headway against these counter-majoritarian practices.

Counter authoritarianism and vigorously defend the democratic community of nations

The United States and its democratic allies are on the front end of a long-term fight to defend their democratic processes as well as their free and open societies from foreign interference and political influence at the hand of authoritarian states. Democracies are not operating on a level playing field: Russia and China have a structural advantage of being closed societies where democratic ideas struggle to compete due to censorship, but neither Russia nor China shy away from engaging in efforts to exploit the open systems of the United States and other democratic countries.40 For these reasons, it is essential that the United States design a more coherent, aggressive, and coordinated response to authoritarian encroachment.

To stem the authoritarian tide and defend democratic processes and institutions, democratic governments will also need the tools and knowledge to push back against the favorite tactics of illiberal regimes seeking to weaken and divide democratic societies. The United States should plan accordingly and lead a collaborative multilateral effort to counter the authoritarian playbook. This plan should involve several lines of effort, including:

- Insulating democratic processes from outside interference and closing vulnerabilities that authoritarian adversaries exploit, for example: outdated and vulnerable electoral infrastructure, porous campaign finance regimes, cybersecurity vulnerabilities in electoral bodies and political campaigns, and weak regulatory frameworks for addressing false or misleading information online41

- Encouraging digital media platforms, social networks, and data firms—the vast majority of which have lacked effective policies for identifying and deterring malign influence operations—to serve as a force for openness, not a tool to be abused by autocrats

- Addressing gaps in the international financial system and domestic laws that enable corruption, money laundering, and illegal campaign finance

- Identifying and sanctioning criminal actors that subvert democratic outcomes by advancing the interests of foreign powers in politics, media, and strategically important economic sectors

- Modernizing U.S. public diplomacy and increasing support to free and independent international broadcast media to better address and rebut the anti-democratic narratives offered by authoritarian regimes

These efforts will only succeed if executed in tandem with other democracies. Some of these lines of effort are likely to advance quickly, while others will take substantial time and investment.

Build global democratic solidarity

Facing an illiberal challenge to the foundations of democratic society, the United States should endeavor to build a liberal bulwark. The first step in this project would be to catalyze deeper cooperation among democratic states. This will require a multipronged diplomatic effort that strengthens a variety of different multilateral and ad hoc networks of democratic states.

Network security alliances

From Europe to Asia and beyond, the United States has formal alliances with a wide range of democracies that constitute some of the world’s most advanced and powerful defense capabilities. The United States should knit together these countries into a broader security architecture to enable better collaboration on regional and global security issues. An increase in security dialogues, technology sharing, and even exercises and interoperability amongst U.S. treaty allies could help bolster the power that democratic countries can project when confronted with global security challenges, from peacekeeping to deterrence to maritime security.

Transform the Community of Democracies into an action-oriented Summit of Democracies

The next administration should seek to transform the existing Community of Democracies (CD) into an annual Summit of Democracies that drives action on key challenges. Currently, the CD is an informal organization that gathers democracies to discuss challenges to democratic governance and to provide technical support to one another on building democratic institutions. Transforming the CD into a more effective institution would require two steps: First, reorient the organization to focus not only on shared threats to democratic societies—corruption, information warfare, and foreign interference in elections—but also shared strategic challenges, such as maritime security and interstate aggression; and second, convene the CD at the head-of-state level annually to endow it with the necessary political and bureaucratic buy-in and follow-through that it currently lacks. Like the idea of a “League of Democracies”42 championed in the past by Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), this organization would be action-oriented—not as a replacement for existing international institutions but to provide an additional, exclusive venue through which leaders of new and transitioning democracies could build relationships with each other and their peers in established democracies. As President Barack Obama’s nuclear security summits demonstrated, the constructive use of the bully pulpit of an American president can be a potent tool in marshaling complex international action.

Promote informal collaboration among democracies to solve key global challenges

The future of international cooperation on major global challenges is likely to be driven primarily by flexible, ad hoc arrangements of like-minded states. Many of these challenges would benefit from the specific cooperation of democracies, as well as regional organizations that make democracy a defining criteria of membership, such as the Organization of American States, the African Union, NATO, and the European Union. The United States should embrace this format of democratic cooperation and form new groupings, especially to act on challenges where democratic principles make a qualitative difference, such as corruption, development, humanitarian crises, and cybersecurity. Such arrangements can play a crucial role in demonstrating that democracies can act effectively and decisively to effect positive change and address pressing problems.

Upgrade the tools of U.S. statecraft to privilege U.S. policy toward democracies

The historic challenge of U.S. democracy promotion efforts is twofold: First, policies that advance democracy can be easily subordinated to near-term security and economic imperatives, and second, democracy promotion efforts are usually under-resourced and not well integrated into broader national security objectives. In a competitive world where the battle of ideas is becoming more intense and the value of the democratic model more contested, the next administration will need to recalibrate and upgrade the tools of U.S. democratic statecraft with the objective of privileging U.S. relationships with democracies and reversing the global democratic slide.

Elevate democracy as a national security priority

Previous U.S. administrations have treated democracy promotion as a noble aspiration but not a key security interest and have accordingly subordinated it to a range of other foreign policy objectives such as counterterrorism, nonproliferation, and economic relations. Going forward, the United States must treat support for democracies as a strategic priority and seek to integrate it with other national security goals. This would translate into a shift from how the United States has traditionally conducted its foreign policy and deployed its powerful tools of statecraft to a new approach that confers special benefits on democracies. While the United States spends significant assistance on democracies—mostly through the MCC and specific economic and democracy assistance programs run by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department—these efforts are diffuse and do not include coordinated whole-of-government efforts to combine economic assistance with security assistance, trade incentives, and other tools.

Launch a Democratic Strategic Advantage initiative

The next U.S. administration should present a multiyear, multibillion-dollar proposal to Congress to create and fund a Democratic Strategic Advantage initiative—akin to past large-scale U.S. government efforts to fight AIDS worldwide—to help established democracies and emerging democratic states sustain progress and to give them a strategic advantage over authoritarian competitors. This initiative would authorize the U.S. government to amplify and better synchronize U.S. economic and security assistance and commercial investment packages. For example, in addition to increased economic assistance, the United States should coordinate its current tools for security cooperation—from arms sales to military training to technology transfer—to give democracies a strategic edge over authoritarian adversaries.

Increase funding for bipartisan democracy organizations

To amplify impact, the United States should ensure that all tools of democracy promotion abroad are running at full speed and able to operate with maximum effectiveness. Congress should accordingly expand funding for the National Endowment for Democracy, the National Democratic Institute, and the International Republican Institute, all of which invest in and work to strengthen democracy worldwide .

Support and defend democratic voices

Most of the successful democratic transitions of the past two decades—such as those in Serbia (2000), Georgia (2003), Nepal (2006), Tunisia (2011), and Ukraine (2014)—had their origins in grassroots movements advocating for peaceful democratic change. Nonviolent resistance can be a powerful tool in pushing back against democratic backsliding, as recent anti-government protests in Armenia and Slovakia illustrate.43 Yet the United States and its democratic partners do not yet have a strategy for engaging, supporting, and defending the rising number of nonviolent pro-democracy movements around the world, in part because of their diffuse, grassroots nature and in part out of concern that external assistance could undermine the legitimacy of such movements. These are valid concerns, but they should not stand in the way of a deliberate and thoughtful approach to peaceful protest. At a minimum, the United States should seek to work with international partners to strengthen international norms regarding the rights of citizens to mobilize peacefully for greater political and civil rights and engage in nonviolent protest against their respective governments.

A key component of this strategy must include significantly ramping up support for civil society in U.S. government programs and policies. In addition to the measure mentioned above, the United States must also make clear that support for nonviolent democracy movements is not about regime change or picking political winners; it is about supporting the universal rights of people to engage in peaceful political expression. Lastly, the United States should seek to deter and punish states that violently crack down on their own people. The United States should make clear that violent repression will trigger strong U.S. economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation.

Challenges

If the United States is to effectively pursue a democratic-values based foreign policy, it must anticipate and proactively address several obstacles to its implementation.

Challenge no. 1

Many will view a U.S. initiative aimed at strengthening democratic values with skepticism. The selling of the Iraq War as an act of democracy promotion and America’s lamentable Cold War history of supporting the overthrow of democratically elected governments fuel suspicion of U.S. foreign policy to this day. For some, the contradictions in America supporting democratic change while working with authoritarian regimes such as that of Saudi Arabia will constitute insurmountable hypocrisy. U.S. shortcomings cannot be papered over but must be considered alongside a larger record of nurturing and protecting democracy in Western and Eastern Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, and elsewhere. The contradictions in U.S. policy are an inevitable byproduct of a pragmatic approach; although they can be mitigated, they cannot be avoided entirely. While the United States must learn from past mistakes and reckon with present contradictions, neither should prohibit a pragmatic pivot toward the protection of democratic values.

Challenge no. 2

The United States cannot—and should not—avoid all cooperation with nondemocratic regimes. National security threats such as climate change, transnational crime, nonproliferation, and terrorism cannot be solved by democracies alone. They require a truly global response. The United States must maintain security, economic, and political cooperation with nondemocratic states, especially China, whose economy and growing influence loom large over the century ahead. America will need nondemocracies to respect and help sustain the global system of rules and norms under which democracies have taken root in every region and to which democratic states appeal for protection against larger authoritarian neighbors. Even as the United States elevates the role of democratic values in its foreign policy, for instance, it should continue to work with countries such as Vietnam to defend freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and Jordan on Middle East peace and security. Concerns over human rights in many cases should not prohibit the United States from engaging in vital cooperation, but nor should that cooperation prevent America from pressing its partners to uphold human rights.

Challenge no. 3

How can America champion democratic values abroad when its own democracy is in trouble at home? Trump is indeed a threat to democracy and has engaged in many of the behaviors—from petty corruption to bullying of law enforcement—that previous U.S. presidents have condemned in other nations. But history teaches us that ideological challenges at home and abroad are in many cases interlinked, and the United States must show it can grapple simultaneously with the need for democratic progress in both the domestic and foreign policy contexts. Today, if American democracy retreats from the global battle of ideas, what fills the void will leave people everywhere less free.

Challenge no. 4

What if America can no longer effectively champion democracy overseas? Democracy is a choice that countries must make for themselves. The United States cannot impose democracy on others, nor should it use military action or subversion to dictate other countries’ politics. But the United States can make clear that it actively supports people’s universal aspiration to govern themselves and that aspiring democracies will enjoy U.S. political support and can expect the United States to enlist other democratic nations to close ranks and do the same. Of course, as the recent backsliding of Hungary and Poland make clear, even robust inducements are rarely determinative. In such cases, the United States must be willing to coordinate closely with other democracies to impose consequences, including imposing penalties on regressive governments. However, the measure of success of a democratic values-based foreign policy should not be perfection but greater progress than under the alternatives—built on the recognition that what matters most is what people on the ground do to shape their own political realities. U.S. support exists not to dictate an outcome but to tilt the balance where possible to favor local aspirations for democratic rights and freedoms.

Conclusion

For more than 70 years, the United States’ ability to do good in the world and secure its international interests has been inseparable from its commitment to democracy at home and abroad. Today, just as democracies around the world face new challenges from without and within, President Trump is chipping away day by day at America’s standing as a force for good in the world.

The present age is not the first time that the United States has seen global democracy in retreat or presided over the decline of its own influence. History has proven more than once that the United States is capable of renewing its own democratic compacts while fighting for its values abroad. While America has not always lived up to its ideals, the truth remains that many people around the world still look to American democracy for inspiration and support. This unique role can and must outlast President Trump. America’s future security and prosperity will in turn depend in large part on whether the United States can continue to defend and lead the world’s democratic community. To prevail over the current illiberal challenge and preserve its place as the world’s leading nation, America needs to revive and harness the power of democratic values.

About the authors

Kelly Magsamen is the vice president for National Security and International Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Max Bergmann and Michael Fuchs are senior fellows at the Center.

Trevor Sutton is a fellow at the Center.