In December 2017, President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans passed massive tax cuts shamelessly skewed toward the wealthy and corporations—a package that promises to jack up the deficit by $1.5 trillion over 10 years. It will also steepen inequality’s upward climb: By 2025, millionaire households will see an average tax cut of $70,000, compared with an average cut of about $200 for a family earning $25,000 per year.

Meanwhile, even before the ink dried on their tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations, members of Congress such as House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) were already insisting that the United States can no longer afford critical programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, demanding deep, painful cuts to these programs in the name of deficit reduction. President Trump echoed Speaker Ryan’s theme, blatantly betraying his promise not to cut Social Security by proposing in his fiscal year 2019 budget a whopping $72 billion in cuts to federal disability programs, including Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), over the coming decade.

In reality, what the United States cannot afford is inequality at its current levels. As income inequality soars to new heights—thanks to policy choices both past and present—it is taking a mounting toll on the financial outlook of Social Security, costing the trust funds more than $1 trillion in the past three decades, as this analysis shows. What’s more, contrary to Speaker Ryan’s agenda, polls show that American voters not only overwhelmingly support Social Security, but the vast majority also want to see it strengthened and improved, not cut—and they would be willing to pay more to make this happen. New polling data released just this month from the Center for American Progress indicates that Americans feel similarly about Social Security’s disability programs, with nearly 8 in 10 Americans opposing cuts to the programs.

When a majority of Americans are saying “hands off” critical programs such as Social Security, policymakers should not be attempting to slash these programs. Instead, they should be taking steps to curb rising inequality and reverse the damage it has done to Social Security’s trust funds.

But hot on the heels of the tax cut’s windfall, leaders in Congress are eagerly handing the richest Americans yet another gift. This year, February 16 is “Valentine’s Day for millionaires”—the day when the last U.S. millionaire earners stop contributing to Social Security for the year. While most working Americans contribute payroll taxes all year long, rich individuals contribute no additional taxes once their earnings exceed Social Security’s payroll tax cap—$128,400 in 2018. For multimillionaire and billionaire earners, who exceed this cap fastest of all, this second Valentine’s Day comes even earlier in the year. Every year that the incomes of high earners rise more rapidly than those of other earners, a greater share of their income escapes Social Security taxation.

Perhaps no one is more accustomed to getting an early Valentine’s Day gift than President Trump himself. Prior to becoming president, Trump stopped contributing to Social Security 40 minutes into January 1, according to his 2016 claim about his income. And as our analysis reveals, many of Trump’s top donors and members of his Cabinet—the wealthiest presidential Cabinet in American history—stop contributing soon thereafter.

This analysis updates previous CAP work demonstrating how much rising inequality has hurt Social Security’s finances in three ways. First, we demonstrate how policymakers’ failure to address rising inequality benefits rich individuals such as President Trump and his Cabinet members and top donors. Second, our analysis shows that if policymakers had maintained Social Security’s payroll tax after 1983 so that it continued to cover 90 percent of earnings—instead of letting its coverage shrink to less than 83 percent as inequality has risen—the combined retirement and disability trust funds would have been larger by more than $1.3 trillion by the end of 2016. Finally, our analysis finds that if American workers’ average wages had risen at the same pace as their productivity from 1983 to 2016, the trust funds would have additional assets of more than $375 billion.

Valentine’s Day gifts come early for Trump, his Cabinet members, and his donors

President Trump and the congressional majority were not content with bestowing a “big, beautiful Christmas present” on billionaires and millionaires through the tax code in December. Thanks to policymakers’ decades-long refusal to adjust Social Security’s payroll tax cap to keep pace with steeply rising inequality—as Medicare’s tax does—millionaire and billionaire earners have already gotten a gift in the new year: an excused absence from further contributing to Social Security.

Their ranks include many members of Trump’s Cabinet, as well as his top donors. According to their most recent reported private-sector salaries, at least eight members of Trump’s inner circle stopped contributing to Social Security fewer than two weeks into 2018, as shown in the text box below. (see methodological note for more information on calculations)

When Trump, his key Cabinet members, and his top donors stopped contributing to Social Security

- January 1: President Donald Trump, $694 million in 2016 (according to his own claim)

- January 1: Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, $138.7 million in 2016

- January 2: Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, $24.6 million in 2016

- January 3: Director of the National Economic Council Gary Cohn, $19.9 million in 2016

- January 3: Billionaire Trump donor Steve Wynn, $15 million in 2016

- January 11: Billionaire Trump donor Sheldon Adelson, $4.6 million in 2017

- January 13: Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, $3.6 million in 2016

- January 13: Fast food czar Andrew Puzder, $3.4 million in 2016

What’s more, these astronomical salaries—most amounting to more in a single day than the typical worker earns in a year—are just the tip of the iceberg. For these individuals, as for many of the richest Americans, a substantial fraction of their income comes in the form of capital gains or inheritance—meaning that every penny evades the Social Security system.

In fact, the most extreme embodiments of inequality in Trump’s inner ring have experienced one extended Social Security tax holiday for nearly their entire adult lives. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos—who, with a net worth of more than $1 billion, is the second-richest Cabinet member—reported only modest taxable wage income compared with her fellow members before being appointed. But the giant fortune she inherited from her father can escape Social Security taxation altogether, as can income produced from stocks and similar investments.

Inequality threatens Social Security—even as its benefits are more vital than ever

For the past eight decades, Social Security has been a bedrock of economic security for millions of American workers and their families. In 2016, 61 million Americans received retirement, disability, or survivor benefits through the Social Security system. And in recent years, the program’s modest benefits have made up more than half of family income for 3 in 5 seniors and 8 in 10 workers with disabilities.

Social Security’s importance to American workers and their families will only grow as the United States stares down the barrel of an approaching retirement crisis; as stagnant pay and an eroding minimum wage make it harder for everyday workers to get ahead; and as the costs of the basic pillars of a middle-class lifestyle continue to outpace families’ incomes. At the same time as many everyday Americans struggle to make ends meet, the incomes of those at the top have pulled ever further away. In 2015, the average household with earnings in the top 1 percent took home 40 times as much as the average household with earnings in the bottom 90 percent—and half of all income in the United States went to the top 10 percent of earners.

Rising inequality is not only leaving everyday Americans further behind every year. As CAP has documented in years past, it is also increasingly inflicting damage on Social Security’s finances through three main channels.

1. Stagnant wages have curbed payroll tax revenues

Workers’ average pay has been failing to keep pace with the output they generate since the early 1970s, with the gains from workers’ productivity instead redirected toward record corporate profits and CEO pay. When that occurs, the revenues from Social Security’s payroll taxes grow more slowly, bringing less money into the combined trust funds than if wages rose quicker. On the flip side, Social Security’s modest benefits become even more critical for workers because slow wage growth and economic insecurity make it more difficult for them to save for retirement during their working years.

2. A growing share of earnings exceeds the payroll tax cap

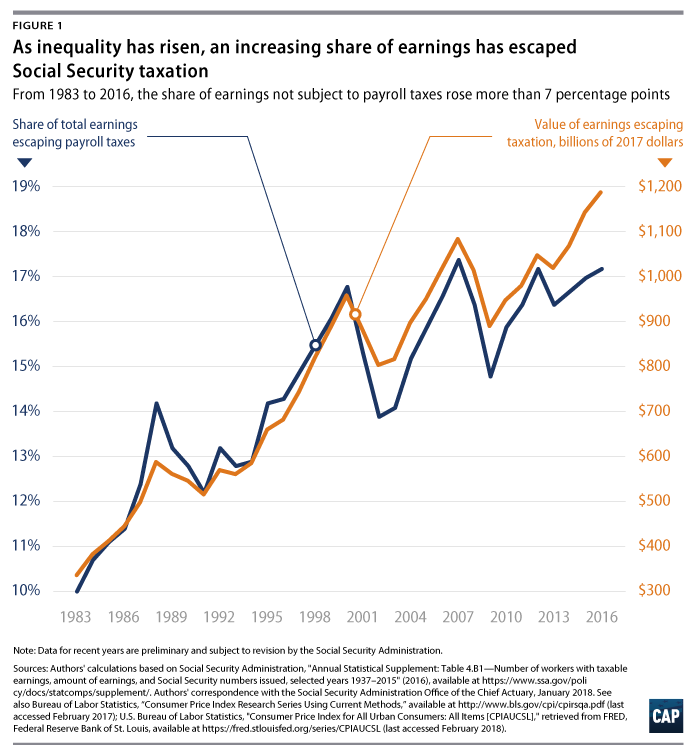

As the richest Americans’ earnings have gotten increasingly higher than those of the average worker, a greater share of total earnings has become concentrated above the payroll tax cap—$128,400 in 2018. Above this cap, a worker’s earnings are exempted from Social Security taxation; thus, concentrated income in the hands of the rich dampens revenues to the trust funds, relative to what revenues would be if earnings were more equally distributed below the cap. While the payroll tax cap generally increases somewhat every year according to the Social Security Administration’s national average wage index, incomes at the top have been far outpacing the index. As incomes at the top have pulled away, the share of total earnings subject to Social Security’s payroll taxes has shrunk from 90 percent in 1983, when Social Security underwent its last major reform, to 82.8 percent today. (see Figure 1)

The payroll tax cap’s failure to keep pace with top incomes is why millionaire and billionaire earners stop contributing to Social Security early in the year, even though the average worker contributes to Social Security in every paycheck throughout the year. In 2018, the last of America’s millionaires with wage income of $1,000,000 stopped contributing on February 16—and higher earners stopped contributing even earlier.

3. Earnings below the payroll tax cap have become less equal

Economic insecurity is dishearteningly common across the economic spectrum, but rising inequality has hurt low-income workers and their families the most—particularly in the 21 states that have not seen a minimum wage increase for eight years and counting. Weekly earnings actually fell for the lowest-paid 10 percent of workers from 1979 to 2014 before finally ticking up starting in 2015—thanks in large part to state-level minimum wage increases—more than five years into the economic recovery from the Great Recession.

Stagnant or declining wages threaten workers’ ability to put food on the table and a roof over their families’ heads. But these trends also put pressure on Social Security’s financial outlook, straining its ability to provide retirement security when workers retire. This is the case for two reasons. First, less revenue comes into the Social Security trust funds through payroll taxes than would be the case if low-wage workers’ wages were rising with productivity growth. Second, because Social Security provides progressive wage replacement when workers stop working—as it should, to maximize the boost to Americans’ economic security—Social Security benefits disproportionately increase when low-wage workers’ wages remain stuck. Thus, benefits grow more quickly relative to payroll tax revenue when earnings inequality beneath the payroll tax cap rises than if inequality were to remain constant.

Simulating inequality’s harmful effects on Social Security

This analysis updates two simulations illustrating how much larger the assets in Social Security’s combined trust funds would be if not for the increase in earnings inequality since 1983. These simulations follow the methods described in a 2015 CAP analysis and address two questions. First, how much greater would the trust funds’ assets have been at the end of 2016 if the share of taxable earnings had remained fixed at 90 percent of earnings since 1983, when Social Security last underwent significant legislative changes? Second, how much greater would assets have been at the end of 2016 if the average worker’s wages had kept pace with productivity growth? These two simulations provide conservative estimates of the effect of rising inequality on Social Security’s financial outlook. (see methodology in CAP’s 2015 analysis)

Our updated analysis shows that if the maximum taxable wage base had been fixed at 90 percent of earnings starting in 1983, the assets in the combined trust funds would have been $1.34 trillion greater at the end of 2016, the last year for which data are complete. This amount alone is enough to cover nearly 11 percent of Social Security’s expected 75-year funding shortfall. And if growth in workers’ wages had kept pace with productivity growth from 1983 to 2016, the combined trust funds would have had an additional $375.6 billion in assets at the end of 2016.

Policymakers must act to reverse rising inequality—not cut vital programs

If President Trump and congressional Republicans believe they can get away with claiming we need so-called entitlement reform—code for cuts to Social Security and other popular programs—after blowing a $1.5 trillion hole in the deficit to give massive tax breaks to the wealthy, they have far too little faith in voters’ memories. Americans should not tolerate this astounding level of hypocrisy from policymakers who have famously fear-mongered about deficits for years.

If President Trump and congressional leaders were serious about addressing pressing sustainability challenges, they would recognize that what is truly unsustainable is the United States’ current levels of income inequality. Fortunately, while inequality poses a real threat to Social Security’s finances, its effects can be addressed with simple, equitable policy changes such as raising the payroll tax cap. But we must not stop there. Policymakers should recognize that Americans across party lines overwhelmingly support all parts of Social Security—especially its vital disability programs—and do not want to see them cut. Rather, policymakers should heed Americans’ call to strengthen the Social Security system to ensure adequate protection in case of disability or loss of a breadwinner, and to provide a secure and dignified retirement for all.

Rachel West is the director of Poverty Research at the Center for American Progress. Rebecca Vallas is the vice president for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center. Eliza Schultz is the research associate for the Poverty to Prosperity Program.

The authors would like to thank Gregg Gelzinis, Alex Rowell, Galen Hendricks, Seth Hanlon, Heidi Schultheis, and Katherine Gallagher Robbins for valuable assistance.

Methodological note

To calculate how long it takes a millionaire or other high earner to finish contributing to Social Security for the year, we first assume that annual compensation is spread out equally throughout the year in which it was reported, and calculate earnings per day. We further assume that each day’s earnings are accrued during a typical eight-hour workday. We then divide by the cap on taxable earnings in that year to yield the number of days required to reach the cap. For Trump Cabinet members, donors, and other affiliates, calculations are based on the most recent available year of data on individuals’ private-sector compensation from financial disclosure statements or the records of publicly traded companies. For the purposes of this analysis, compensation includes salaries and bonuses as well as stock options, which are all incorporated as though exercised in the year received. Compensation excludes such items as nonequity incentive plan compensation, honoraria, the value of health care plans, and employer matches to and distribution of excess savings plans. (see text box above for sources; full info is on file with authors)