Early in his presidency, President Donald Trump promised to “send in the Feds” to address what he described as “carnage” based on his depiction of violent crime issues in cities like Chicago.1 One of the president’s first actions was to sign an executive order establishing a federal task force, comprised only of federal employees, to explore how the federal government should address crime in local U.S. jurisdictions.2 This task force soon will provide recommendations on what policy changes the U.S. Department of Justice should implement, but Attorney General Jeff Sessions already has instituted a shift toward a public safety strategy heavily reliant on more arrests and incarceration.3

This approach, however, is dangerous and based on false premises: There is no nationwide American carnage, and the federal government is not equipped to take the lead on public safety efforts in cities where violent crime rates have increased.

The situation in cities like Chicago certainly needs significant attention and support. The number of homicides committed in Chicago in 2016 was 57 percent greater than the year before.4 However, it is crucial to be accurate in describing crime and violence so that the strategies deployed are targeted to address the actual need. For example, several recent studies have indicated that the increase in homicides over the past two years have been driven overwhelmingly by a select number of cities, and that violent crime rates in other large metropolitan areas, such as New York City, have decreased or held steady.5

It is equally important to consider carefully the role of the federal government in addressing crime, especially considering the damage done the last time the federal government took the lead on public safety efforts. Known as the War on Drugs, that federally led effort traces its roots back to the late 1960s and accelerated through the next three decades, dramatically increased federal prison sentences for drug offenders and led to the mass incarceration of a generation—particularly young African American men—devastating their families and whole communities. These effects continue to this day.6

The failure of these policies does not mean that the federal government has no role in public safety, however. While public safety is generally a local issue, Washington has an important and distinctive role in both supporting and checking local efforts. This report examines three effective and appropriate ways the federal government can utilize its resources to help local communities address and prevent violent crime:

- Fund comprehensive crime prevention

- Provide robust oversight of the gun industry to reduce illegal gun trafficking

- Build trust between police and communities through accountability

These actions make the best use of the unique assets that the federal government can offer, while allowing local law enforcement to lead crime reduction and prevention efforts. Instead of declaring a federal takeover of violent crime reduction efforts that could perpetuate the era of mass incarceration, this report argues for proven strategies that this Administration has discounted. It also advocates careful consideration regarding the manner and degree to which the federal government provides assistance to local jurisdictions.

Local authorities have the primary responsibility of reducing crime, maintaining public order, and keeping communities safe. Because local institutions are part of their communities, they know the factors driving local criminal activity and are invested in long-term positive outcomes. Such outcomes are dependent on reducing or keeping crime rates low. Safe communities result in better schools and higher academic performance by students, increased economic investments and more jobs, and better physical and mental health for all community members.

The Constitution gives this role to local jurisdictions. Under the Tenth Amendment, States, and by extension their subdivisions of counties and cities, have general police powers to pass and enforce laws that govern the safety and well-being of the public.7 The federal government’s authority is limited to those public safety issues where a nexus exists to a specific constitutional provision, such as enforcement of immigration laws or those that affect interstate commerce. For example, crimes such as robbery of a home fall under the general police powers of a state, while bank robbery can be prosecuted federally if the robbed institution was insured by a federal entity such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.8

When crime rates rise and become concerning for local communities, however, it is not uncommon for states and localities to request assistance from the federal government. Often, the type of assistance provided centers around sharing the expertise and technology of federal law enforcement agencies; expanding task forces comprised of local, state, and federal authorities that facilitate coordinated operations; and prosecuting cases in federal court. While these tools can and should be shared in deliberate ways, limiting federal public safety assistance to the province of the FBI or U.S. attorneys, as the administration is suggesting, restricts the variety of other necessary, valuable, and collaborative resources that may be more effective at reducing crime over the long term.

Did so-called law-and-order policies reduce crime?

The federal government is resurrecting antiquated law and order policies that were popular when Attorney General Sessions was last a law enforcement official two decades ago, in Alabama. A casual look at crime rates since 1991—the peak of violent crime in America—may lead some to conclude that the substantial crime decline over the next two decades resulted from the tough on crime policies of the 1980s and 1990s. Yet, substantial research since the 1990s shows that incarceration rates have little long term effect on crime rates:

- The National Academy of Sciences conducted a review of research that studied the effect of incarceration on crime and concluded, “Most studies estimate the crime-reducing effect of incarceration to be small and some report that the size of the effect diminishes with the scale of incarceration.”9

- According to a study by the Sentencing Project of the relationship between crime rates and incarceration in the 1990s, states that had incarceration rates below the national average experienced lower crime rates than states that had above average incarceration rates.10

- A Pew analysis of state crime and incarceration rates between 2010 and 2015 showed similar results: States with larger drops in incarceration rates had larger decreases in crime rates,11 which shows at least that increasing incarceration was not a driving factor in reducing crime.

Moreover, the effect of those ineffective policies had life-long detrimental consequences for affected communities, especially African Americans:

- According to a 2017 study, African Americans in the United States are more than twice as likely as whites to be arrested for drug crimes. The researchers found that these disparities cannot be explained by differences in offending or community context.12

- A 2015 study found that the tough on crime policies of the 1980s and 1990s increased the likelihood that juvenile boys, especially black and Hispanic boys, are charged and placed in correctional institutions rather than a diversion program or counseling.13

- According to one study, had sentencing guidelines treated crack and powder cocaine the same for equal amounts of the drug—rather than a 100 to 1 disparity—the average sentence for an African American trafficker in the 1980s and 1990s would have been 10 percent shorter than that of a white trafficker. Instead, sentences were 30 percent longer on average.14

Unfortunately, the likelihood that the federal government will abandon its heavy-handed law and order approach is low, even in the face of bipartisan opposition.15 Compounding the problem is the administration’s insistence on requiring local law enforcement to take on additional federal immigration enforcement responsibilities.16 This report therefore highlights three strategies that the administration has discounted but that are nonetheless complementary to local law enforcement efforts. Implementing the following three strategies would improve long term public safety outcomes and make the best use of limited, unique federal assets:

- Fund comprehensive crime prevention

- Provide robust oversight of the gun industry to reduce illegal gun trafficking

- Build trust between law enforcement and communities through accountability

Fund comprehensive crime prevention

The federal government has the distinction of being the largest funding source for criminal justice and public safety issues to state and local governments, researchers, and service providers. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) doles out $4 billion in grants, training, and technical assistance, in addition to related initiatives from the U.S. Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, Labor, and Housing and Urban Development.17 Because states and localities rely on federal funding as a major source of their crime prevention and reduction strategies, the goals of the grants inevitably shape the public safety approaches of their recipients.

Studies have consistently shown that the most effective way to reduce crime is to utilize a menu of options that combines enforcement with prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation.18 Yet, the Justice Department’s current strategy to address violent crime is singularly dependent on ramping up and leading enforcement efforts around the country, as reflected in its fiscal year 2018 budget proposal. The Justice Department’s request for Combatting Violent Crime calls for a nearly $200 million increase to dramatically enlarge programs and initiatives focused solely on enforcement activities.19 This includes increases in the numbers of federal prosecutors, law enforcement agents, task forces, and transnational investigations.

What it is striking about the DOJ budget is that every enhancement listed to combat violent crime is related to a law enforcement or prosecutorial activity. Moreover, the dramatic increase in funding for enforcement activities necessarily results in significant spending cuts elsewhere, due to finite federal resources. It is no surprise, then, that if there is no obvious nexus to enforcement activities, the administration proposes substantially scaling back the criminal justice and public safety funding it provides to states and localities.

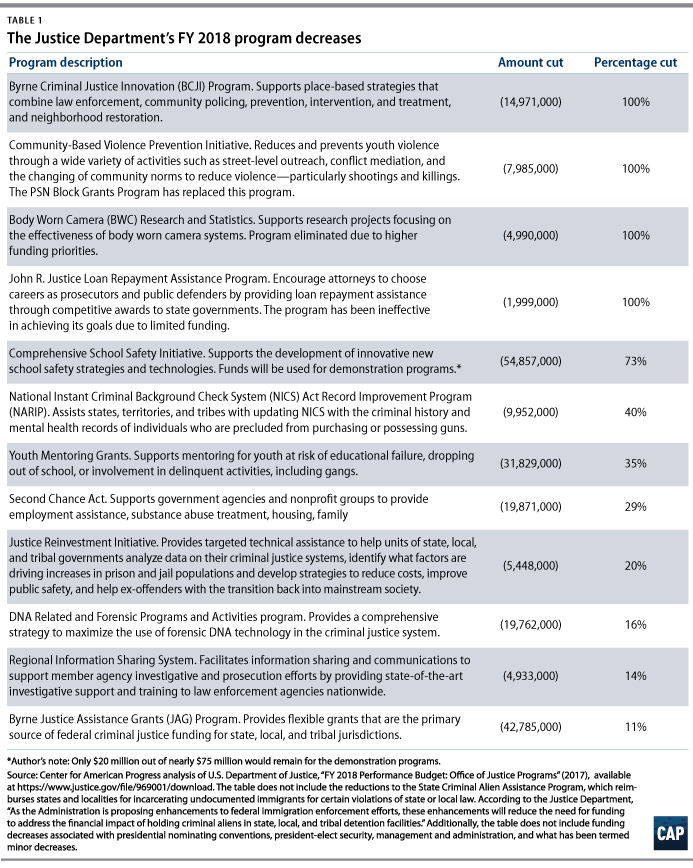

In total, the administration proposes to cut more than $200 million in funding that supports comprehensive public safety and criminal justice efforts. The Office of Justice Programs (OJP) is DOJ’s largest funding source to state and local entities for criminal justice and public safety efforts. Of the 13 OJP programs identified for funding decreases in FY 2018, 11 do not have a direct nexus to enforcement operations. (see Table 1) For example, funding for the Second Chance Act, which supports recidivism reduction through successful reentry of people returning to their communities from incarceration, is cut by 30 percent. The Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation program is cut entirely, as are other place-based violence prevention efforts that do not necessarily rely on law enforcement activity. And youth mentoring grants are reduced by nearly two-thirds.

Many of the downsized programs were instrumental in starting or cultivating innovative violence reduction efforts. The Community Based Violence Prevention initiative, which the Trump budget eliminates, helped amplify hospital based interventions focused on preventing the cycle of violence. This is a classic public health approach to violent crime prevention, in which community-based social services begin when a victim of violent crime is being treated in the hospital for physical injuries and the trauma associated with victimization. Services, including counseling, help prevent victims from retaliating against perpetrators and focus instead on future opportunities. In past years, cities like Philadelphia and Oakland championed this approach with support from the Justice Department.20

In Chicago, past partnerships with the Justice Department yielded positive violence prevention results. One Summer Chicago, for example, provided summer employment to high school students from disadvantaged neighborhoods. The 2012 program not only provided eight-week part-time summer jobs but also assigned an adult mentor to participants and taught the young people ways to manage their emotions and behavior. The results from a randomized control study of the program showed that violent crime arrests among participants decreased by 43 percent compared with the young people in the control group. Even more startling was the finding that the decrease occurred in the 16 months after the end of the program, demonstrating the positive lingering effects of this type of intervention.21

The program decreases also reflect the Justice Department’s effort to supplant local public safety efforts. The DOJ budget takes away $43 million from the Byrne Justice Assistance Grants (JAG), the largest source of federal justice-related funding to states.22 States and localities receive those funds according to a set formula that considers population and crime rates, and the decision of how to use JAG funds rests with the state or locality receiving them—whether that is law enforcement, courts, or crime prevention. DOJ is now proposing to use the JAG cuts to help fund a $70 million increase for Project Safe Neighborhoods, an enforcement effort led by a U.S. attorney. In other words, the federal government would be directing communities as to how they should spend millions of dollars over which they previously had local control.

This federal takeover of public safety and criminal justice efforts is alarming, especially because it also promotes policies that have been proven ineffective. To truly support local efforts to reduce crime, DOJ should continue to follow the evidence and combine any enforcement efforts with proven prevention strategies that provide opportunities for those at risk of being a victim or perpetrator of crime.

Provide robust oversight of the gun industry to reduce illegal gun trafficking

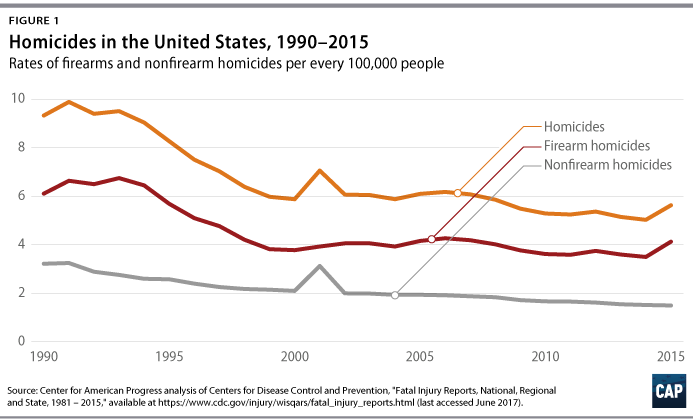

While the Trump administration has made much of the recent rise in violent crime in some American cities, it has largely failed to acknowledge one of the key drivers of lethal violence in the United States—access to firearms. While homicide rates are down nationwide from a high of 9.89 per 100,000 people in 1991 to 5.63 per 100,000 in 2015, guns account for a substantial portion of the homicides that continue to occur. In 2015, the most recent year for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, gun murders accounted for 73 percent of the nearly 18,000 homicides in the United States.23 The role of gun access in murder rates is evident in a number of the cities that have seen recent increases in homicides. For example, in 2014, gun murders accounted for 72 percent of all murders in Chicago, 67 percent of all murders in Houston, and 67 percent of all murders in St. Louis.24

Any federal effort to assist local law enforcement agencies in preventing gun homicides requires more than simply increasing the number of federal agents detailed to a particular city or increasing the number of federally prosecuted cases involving individuals who use guns in the commission of a crime, as Attorney General Sessions has proposed.25 One of the most challenging aspects of local efforts to prevent gun violence is preventing the illegal trafficking of guns into vulnerable communities. Many states and cities have enacted strong laws to prevent gun trafficking—such as requiring background checks for all gun sales, requiring a permit to purchase a gun, and mandating reporting of lost or stolen guns—but these laws are often undermined by the failure of other states to take similar steps. The result is a steady flow of guns from states with relatively weak gun laws to states with stronger laws. According to U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) trace data, from 2010 to 2015, 29 percent of all crime guns submitted for tracing crossed state lines before being used in a crime.26 In some states, this problem is particularly acute. A recent analysis by the New York State Office of the Attorney General found that from 2010 to 2015, 86 percent of handguns recovered in connection with crimes in New York were originally purchased from out-of-state gun dealers.27

The ATF has a substantial role to play in helping reduce illegal gun trafficking into communities facing an increasing number of gun homicides. In addition to its role as a federal law enforcement agency with a mandate to enforce federal gun laws, ATF’s mission has a second prong that is unique among every other U.S. law enforcement agency: to provide regulatory oversight of the gun industry. ATF describes the two aspects of its work as “interwoven to provide a comprehensive approach to its mission.”28 The regulatory prong is a crucial part of ATF’s work to address violent crime. One of the core activities of ATF’s regulatory staff is conducting compliance inspections of licensed gun dealers to ensure that they are maintaining proper control over their dangerous inventory and complying with all federal laws and regulations governing the operation of their businesses.29

Nearly every gun that ends up illegally trafficked and used in the commission of a crime begins as part of a licensed gun dealer’s inventory. Therefore, robust oversight of these dealers is a vital part of preventing the diversion of guns into illegal trafficking networks. During ATF compliance inspections, tens of thousands of guns are found to be missing from gun dealers’ inventories every year, either due to theft, illegal off-the-books sales by dealers, or negligent recordkeeping. These missing guns pose a substantial challenge for local law enforcement agencies. The guns are often diverted into illegal gun trafficking networks where they become untraceable and end up being used to commit homicides and other violent crimes.30 In the past five years, 88,700 guns have been discovered to be missing from gun dealer inventories during ATF compliance inspections.31

While ATF is authorized under federal law to conduct an annual inspection of every licensed gun dealer and has established an internal goal of inspecting every gun dealer at least every three years, resource limitations have left the agency far short of meeting that goal. In 2016, ATF inspected only 9,790 licensed gun dealers in the country, which accounted for only 7 percent of licensed dealers nationwide.32 A 2013 Office of the Inspector General investigation found that between 2007 and 2012, more than 58 percent of gun dealers had not been inspected for more than five years.33 ATF acknowledges the risk posed by these infrequent inspections; its FY 2018 budget request stated that “[t]he lack of timely inspections presents a significant risk to public safety.”34 In its FY 2017 budget request, ATF requested an additional $35.5 million to add 200 new positions, including 120 additional regulatory investigators, to help fill this gap.35 However, this request was not included in the Trump budget request, leaving ATF to continue struggling to provide adequate regulatory oversight of gun dealers.36

Furthermore, if the Trump administration is serious about using federal law enforcement resources to assist in local efforts to reduce violent gun crime, it should work to eliminate the onerous restrictions that limit ATF’s ability to function in an efficient and modern manner. There are currently more than a dozen restrictive policy riders attached to ATF’s budget that limit the agency’s ability to manage data using modern technology, that interfere with disclosure of data crucial to law enforcement and research, and that frustrate efforts to regulate gun dealers.37 These harmful riders should be eliminated to enable ATF to be a fully effective partner in local law enforcement efforts to investigate gun-related crime and provide robust oversight of the gun industry.

Build trust between police and communities through accountability

Trust is a necessary and effective crime-fighting tool. If law enforcement is to investigate crimes and hold perpetrators accountable, it must rely on human witnesses in the vast majority of cases. Trust is essential, especially for victims who survive violent crimes and experience trauma and fear retaliation from perpetrators. Thus, when the relationship between law enforcement and the community it serves is strained or severed, the ability to investigate and hold those who commit crimes accountable is severely hampered, and crime rates cannot be reduced.38

In the United States, trust between law enforcement and people of color, especially African Americans, remains low. A 2016 Pew survey shows that African Americans hold a significantly more pessimistic view of the way police conduct themselves on the job compared with their white counterparts.39 This is consistent with surveys by other organizations such as Gallup and is virtually unchanged from previous years.40

A crucial aspect of community trust and improving policing in this country is ensuring that law enforcement is accountable to the community it serves. Some policymakers point to civilian review boards – organizations that are officially recognized by a jurisdiction and composed of community members who review complaints made against law enforcement officers – as a model of police oversight. Yet, these boards often are not sufficiently funded or given the necessary authority to properly investigate an incident. They also are subject to political pressure and therefore are not truly independent bodies.41

Local oversight in Chicago

In Chicago, two entities are tasked with law enforcement oversight: the civilian complaint review board, known previously as the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), and the Chicago Police Department’s Bureau of Internal Affairs (BIA). The results of their efforts in recent years have been substandard:

- Average number of complaints per year, 2012-2015: 7,00042

- Average percentage of complaints sustained,* 2012-2015: 1.4 percent43

- Total amount Chicago paid to settle police misconduct lawsuits, 2012-2015: $210 million44

- Cost of Chicago’s mentoring program per year: $12 million45

- Cost of One Summer Chicago for 31,000 summer jobs: $26 million46

In order to institute a more rigorous examination of police misconduct, Chicago is in the process of replacing the IPRA with a Civilian Office of Police Accountability.

* “Sustained” means that the complaint was supported by sufficient evidence to justify disciplinary action.

Moreover, civilian oversight boards often lack the scope and authority to examine and reform police departments when they have demonstrated systemic and structural problems. In these situations, an outside investigation is needed, including avenues for the federal government to provide accountability. After Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers beat Rodney King in 1992—and the LAPD failed to hold the officers accountable—Congress held multiple hearings to determine what role the federal government could play to help address police misconduct across the country. As a result, Congress provided the U.S. attorney general with the authority to “investigate and litigate cases involving a pattern or practice of conduct of law enforcement officers that violates Constitutional or federal rights.” This authority is commonly known as “pattern or practice” cases brought by the Civil Rights Division within the Department of Justice.47

In many cases, consent decrees have been found not only useful but also essential because of the lack of other effective local monitoring efforts. While Attorney General Sessions has said that consent decrees are dangerous, provide an “end run around the democratic process,” and that the federal government should not have a role in local police oversight,48 in 2013, the Police Executive Research Forum conducted a comprehensive review of DOJ’s role in monitoring local police departments and found otherwise. Its report revealed that many police chiefs not only welcomed support from the federal government but also that “the result was a better police department—with improved policies on critical issues such as use of force, better training of officers, and more advanced information systems that help police executives to know what is going on in their department and manage their employees.49

Unfortunately, Chicago has taken the opposite track as Baltimore, recently backing out of its commitment to have its police reforms monitored by a federal court. This step has been widely criticized, especially because local institutions have not adequately conducted their law enforcement oversight responsibilities.50 To ensure public safety, trust between community members and local police officers is essential. Failure to provide accountability not only for bad apples in departments but also for systemic structural issues will only fuel the current, longstanding tension between communities of color and law enforcement.

Ed Chung is the vice president for Criminal Justice Reform at American Progress. His work focuses on promoting smart criminal justice policies and interventions that are fair and effective. Previously, Chung served as senior adviser on criminal justice, policing, and civil rights issues for the Assistant Attorney General of the Office of Justice Programs at the U.S. Department of Justice. In that capacity, Chung coordinated a national initiative for building trust between the justice system and the communities it serves, as well as the Obama administration’s violence reduction and second-chance efforts under the My Brother’s Keeper initiative. Chung also held positions in the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, including special counsel to the assistant attorney general and federal prosecutor with the Criminal Section. He also was senior policy adviser at the White House Domestic Policy Council; counsel to Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) in the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary; and assistant district attorney at the New York County District Attorney’s Office in Manhattan.

Chelsea Parsons is the vice president of Guns and Crime Policy at the Center for American Progress. Her work focuses on advocating for progressive laws and policies relating to gun violence prevention and the criminal justice system at the federal, state, and local levels. In this role, she has helped develop measures to strengthen gun laws and reduce gun violence that have been included in federal and state legislation and as part of President Barack Obama’s January 2016 executive action announcement on gun violence prevention. Prior to joining the Center, Parsons was general counsel to the New York City criminal justice coordinator, a role in which she helped develop and implement criminal justice initiatives and legislation in areas including human trafficking, sexual assault, family violence, firearms, identity theft, indigent defense, and justice system improvements. She previously served as an assistant New York state attorney general and a staff attorney law clerk for the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Danyelle Solomon is the director of Progress 2050 at American Progress. Previously, she served as policy counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Washington, D.C., office, where she focused primarily on criminal justice issues, including sentencing reform, corrections reform, policing reform, commutations and pardons, and racial disparities in the justice system. Prior to joining the Brennan Center, Solomon served as legislative counsel at the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy within the Office of Legislative Affairs, where she focused on federal drug policy. Solomon also served as counsel to Sen. Benjamin L. Cardin (D-MD), then the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Terrorism and Homeland Security Subcommittee. Solomon was responsible for a wide array of policy issues, including sentencing reform, juvenile justice reform, civil rights, and executive branch nominations; she also served as the principal counsel to Sen. Cardin during the U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.