Women and men across different races, ethnicities, ages, and socioeconomic levels overwhelmingly support equal pay for equal work. Yet the lack of equal pay and persistent pay disparities remain a concern, particularly for working women, who continue to experience a significant wage gap compared with their male counterparts.

Currently, women who work full-time year-round in the United States make, on average, just 80 cents for every $1 earned by men.1 For women of color, these disparities are even starker.2 (see Figure 1)

To combat pay discrimination and help close the gender wage gap, we need comprehensive solutions to strengthen existing protections and target pay practices that can lead to discrimination. This means promoting greater pay transparency to help root out discriminatory practices; protecting workers from retaliation if they discuss their pay with others; requiring employers to disclose pay data to enforcement officials regularly to ensure compliance with the law; adopting strong penalties for legal violations to deter discrimination; and eliminating legal loopholes that make it easier for employers to avoid liability for pay disparities.

Yet, partisan divisions among policymakers have stymied efforts to adopt comprehensive, national solutions to ensure that workers are paid fairly and can support their families. Conservatives have used rhetoric and obstruction to question whether equal pay is still a problem, rationalize the gender wage gap, and derail proposed reforms in favor of limited policy approaches or complete inaction.

For years, opponents have blocked the two leading proposals that offer comprehensive strategies to strengthen equal pay protections: the Paycheck Fairness Act and the Fair Pay Act of 2015.3 Both bills focus on closing gaps in existing law to make it easier to challenge pay disparities, injecting more transparency and accountability around pay decision-making, and encouraging employers to be more vigilant about their pay practices. In September 2016, Reps. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC), Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), and Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) introduced a complementary bill—the Pay Equity for All Act—to limit employers’ ability to ask questions about salary history during the hiring process.4 These proposals collectively would help improve workplace pay practices, root out discrimination, strengthen enforcement, and better position workers to make sound decisions about their pay.

Opponents have largely rejected the need to take action in support of equal pay.5 But, in an apparent effort to appear responsive to worker concerns, some conservative lawmakers have offered narrower, but ultimately inadequate, alternative plans. Sen. Deb Fischer’s (R-NE) Workplace Advancement Act proposes a limited anti-retaliation protection for those who discuss their pay, but its reach is unclear.6 Sen. Kelly Ayotte’s (R-NH) Gender Advancement in Pay Act is broader but has gaps in enforcement protections that would diminish its impact.7 Even if these limited proposals had more merit, lawmakers have neither debated nor considered either, raising broader questions about conservatives’ commitment to addressing equal pay concerns and whether these proposals are simply efforts to check a box to feign support.

Separating myth from reality

Policymakers can take steps to promote equal pay, ensure that workers are paid fairly, and close the gender wage gap. To move forward, it is critical to separate myths and rhetoric from real-world solutions that would make a difference for working families.

Myth: Necessary equal pay laws are already on the books

Reality: While there are laws that prohibit pay discrimination and require equal pay for equal work, they simply have not been updated to reflect 21st-century workplace realities. The Equal Pay Act has been on the books for more than 50 years, but unfortunately, courts have narrowed the law’s reach over time.8 Some courts, for example, have interpreted the defenses available to employers under the Equal Pay Act broadly, making it easier for employers to assert any non-gender-based reason as justification for a pay difference and avoid liability.9

Additionally, the Equal Pay Act does not specifically mention other issues such as pay transparency and pay secrecy rules, even though such rules can shield discrimination and depress wages. The Paycheck Fairness Act and the Fair Pay Act would strengthen the Equal Pay Act and ensure that all workers have access to more comprehensive protections.

Myth: The fact that the gender wage gap has persisted after the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act shows that legislation is not the answer

Reality: The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, signed by President Barack Obama in 2009, was an important step forward in the fight to end pay discrimination, but its purpose was to regain lost ground and return to the status quo. It did not go beyond current law to bolster existing Equal Pay Act protections or to identify new strategies to close the wage gap.10 Rather, it responded to the controversial 2007 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.11

In Ledbetter, a divided Supreme Court ignored decades of case law to severely narrow the timing requirements for filing pay discrimination claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. If the Court’s decision had been left standing, it would have barred many Title VII pay discrimination claims from moving forward. The Court ruled that workers must file such claims within 180 days of the initial discrimination—a nearly impossible task, given that pay discrimination is difficult to uncover. The Ledbetter Act rejected the Court’s interpretation and restored the prior rule, which gives workers 180 days from the last discriminatory paycheck to file their claims. The purpose of the Ledbetter Act was to correct a specific interpretation of law raised in the Ledbetter Supreme Court ruling; it did not address the broader need for stronger Equal Pay Act protections to ensure that workers have the most robust anti-discrimination protections possible. It also did not focus on providing comprehensive strategies to address the different factors fueling the wage gap—including discrimination.

Myth: Pay discrimination is no longer a problem and does not explain the gender wage gap

Reality: There are several different factors that cause the gender wage gap. Some of the wage gap can be explained by factors such as differences in education or seniority, but there is an unexplained portion of the gap that researchers often attribute to pay discrimination.12 The fact that pay discrimination is only one factor contributing to the gender wage gap does not relieve employers of their obligation to combat discriminatory pay practices. Most employers have an ongoing legal obligation to avoid pay discrimination and to ensure equal pay for equal work. This means that employers are required to take steps to comply with the law at all times, regardless of whether there is a wage gap among their employees or not. Women consistently identify unequal pay as a workplace problem.13 But violations are often cloaked in secrecy, difficult to uncover, and hard to prove. Ensuring that both women and men have strong protections against pay discrimination is critical.

Myth: Women’s occupational choices can explain the gender wage gap

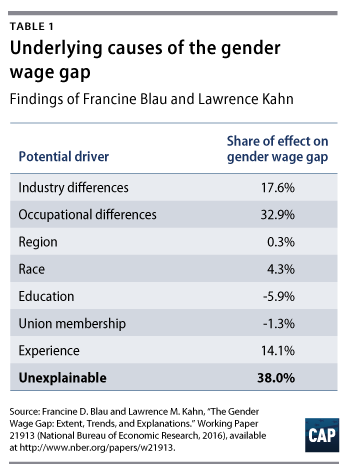

Reality: Research consistently shows that multiple factors are driving the gender wage gap. The American Association of University Women has found that the wage gap among college-educated women begins one year after graduation—before life decisions may influence women’s earnings—and that it grows over time.14 Cornell University economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn have broken down the different elements of the gender wage gap to quantify the impact of each element. Their most recent analysis found that 38 percent of the wage gap could not be explained but could be partially due to discrimination15

This research makes clear that dismissing the gender wage gap as simply a reflection of women’s choices ignores the gap’s underlying causes. These causes deserve greater attention.16 For example, the dearth of affordable caregiving options and workplace policies that accommodate work-family needs often drives women to spend more time out of the workforce than men17 Some parents may choose to leave the workforce and stay home with their children full time, but in most households with children, all adults work—usually out of economic necessity.18 Many mothers are pushed out of the labor force because child care would cost more per year than they earn or because they are not able to find a job that provides the flexibility necessary to care for a child.19 Working parents without access to paid sick days or who are not eligible for job protection through the Family and Medical Leave Act may lose their jobs if they experience a family caregiving emergency.20

Many policymakers who deny the wage gap argue against paid family leave, paid sick days, affordable child care, and workplace flexibility. Yet research shows that when such policies are provided, mothers are able to return to work more quickly after childbirth, work longer hours if desired, and be more productive, all of which can help narrow the wage gap.21 The gender wage gap is multifaceted, which means that addressing it requires a holistic approach. Policymakers need to advance a comprehensive strategy that includes enacting equal pay protections and expanding access to modern workplace protections such as paid family and medical leave, earned sick days, affordable child care, and fair scheduling.22

Myth: To close the wage gap, women just need to get better jobs

Reality: Telling women that they simply need to get better jobs ignores the breadth and depth of the problem. In the vast majority of occupations, women earn less. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in 2015, out of at least 115 occupations with comparable data, men earned more than women in all but five occupations.23 In jobs that are predominantly female—such as elementary school teachers, maids and housekeepers, and registered nurses—women still earned less than men.24 In fact, in the 25 most common occupations for women, women still saw an overall wage gap of 81.9 percent.25 And jobs with a higher percentage of women workers offer lower starting wages and have slower wage growth—or steeper wage decline—for both women and men in the ensuing years.26

Furthermore, traditionally female-dominated occupations tend to be lower-paying than male-dominated occupations. Cultural norms can push women and girls into lower-paying so-called women’s work fields—in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Recent studies of women in science, technology, engineering, and math occupations found that women generally have higher attrition rates than their male peers and women in other fields. A 2008 study found that by midcareer, 52 percent of female scientists, engineers, and technologists had quit their jobs. Women in the study cited feelings of isolation, unsupportive work environments, unclear rules about advancement and success, and extreme work schedules as key reasons for leaving these occupations. Additionally, many women in these fields may experience explicit or implicit gender bias that negatively influences their participation in the field.27 Moreover, research has shown that when women enter a traditionally male-dominated field in large numbers, pay in that field declines even after controlling for education, work experience, skills, race, and geography.28

Myth: Ending retaliation against workers who discuss their pay is enough to ensure equal pay and close the wage gap

Reality: While prohibiting retaliation against workers who discuss their pay can help combat pay secrecy and close the gender wage gap, it alone is insufficient. Protecting workers who discuss their wages primarily helps people after the fact to find out if they have been discriminated against. Protections may also discourage some employers from engaging in discrimination in the first place.

But other proactive steps are sorely needed to strengthen equal pay protections and prevent pay discrimination. A proposal such as the Workplace Advancement Act is woefully inadequate because it fails to provide the comprehensive protections needed to address pay discrimination.29 Moreover, the anti-retaliation protection it purports to provide is too narrow to protect workers from employer retaliation for discussing wages. To be covered, employees must prove that they were discussing wages in an effort to determine whether they were being paid unfairly. It is unclear whether workers who cannot prove this would be protected from employer retaliation.

Myth: Women earn less because they ask for less

Reality: While stronger negotiation skills could help some women get higher pay—indeed, the Paycheck Fairness Act would provide grants for negotiation skills training—they are not a cure-all. Research has shown that women are penalized far more harshly for negotiating than men. In one study, participants viewed video clips of men and women negotiating for higher wages. Viewers perceived the men’s negotiating style as smooth, while they perceived women using the identical script as too demanding.30 When women are faced with a negotiating opportunity, therefore, they must weigh the benefits of negotiating against the social consequences—and potential job risks.31

Myth: Increasing damages will just encourage frivolous lawsuits and make lawyers rich

Reality: The argument that the potential for higher damages will encourage frivolous lawsuits is a common excuse that ignores the difficulty in pursuing pay discrimination claims. Studies show that people who bring employment discrimination cases tend to be less successful than other civil claimants.32 Cases often take years to conclude, making quick windfalls highly unlikely. Moreover, the pressures that come with long, drawn-out litigation can increase stress at work and at home, regardless of the size of any potential damages award. At the end of the day, damages should be significant enough to be a deterrent and discourage bad pay practices. Workers who have been paid unfairly should have access to remedies that reflect the losses they have suffered.

Myth: Data collection efforts are unnecessary and onerous for businesses and will lead to sensitive personal information being made public

Reality: This concern is a red herring. Enforcement agencies’ collection of pay data is a critical tool to ensure compliance with the law. There are myriad protections already in use to prevent confidential information from being made public, and none of the pending bills would weaken these protections.33 It is vital that enforcement officials have full access to the pay data they need to evaluate employer pay practices, investigate pay discrimination claims, and assess occupation and industry trends. Such information can be provided without imposing extensive burdens on employers.

Conclusion

Workers have a vested interest in ensuring that women and men are paid fairly, combating discriminatory pay practices, and closing the gender wage gap. Lawmakers should be equally committed to achieving these goals. In order to meet the needs of working families, policymakers must reject the myths and rhetoric used to deny the persistence of pay discrimination and the gender wage gap, and instead support robust policies to strengthen the law. Comprehensive solutions would promote pay transparency, protect workers from employer retaliation for discussing their pay, require pay data disclosure to enforcement officials, and enhance enforcement efforts where needed.

Watered-down proposals that address these principles in name only are unresponsive and unhelpful and lack the substance necessary to ensure equal pay or diminish the gender wage gap. They may check the box for conservatives, but they will do little for working families.

Indeed, while it is crucial to have robust equal pay laws, lawmakers must also take concrete steps to address the other major contributing factors to the gender wage gap. Such action must address the lack of access to family-friendly workplace protections—such as paid family and medical leave, earned sick days, affordable child care, and flexible scheduling—that women and men need to fulfill their work and family obligations. These policies are essential to ensuring that all workers have the best chance to succeed at work and at home and provide crucial resources to their families.

Kaitlin Holmes is a Special Assistant for the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress. Jocelyn Frye is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Sarah Jane Glynn is a Senior Policy Adviser at the Center. Jessica Quinter is a former intern with the Women’s Initiative at the Center.