Though the fiscal cliff deal passed by Congress late on New Year’s Day will raise a substantial amount of new revenue over the next decade, the resulting revenue levels will still be significantly below what bipartisan experts believe we will need in the medium term and far lower than the last time the budget was balanced. And despite any protestations from antitax advocates, the tax increases in the deal are actually relatively slight compared to other tax hikes of the past.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012—the fiscal cliff legislation agreed to in a deal between President Obama and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY)—will raise approximately $617 billion in higher revenues from 2013 to 2022, compared to what the tax code would have generated if we had simply extended all the Bush tax cuts, which were scheduled to expire at the end of 2012. More than 90 percent of the increase will come from households making at least $1 million a year.

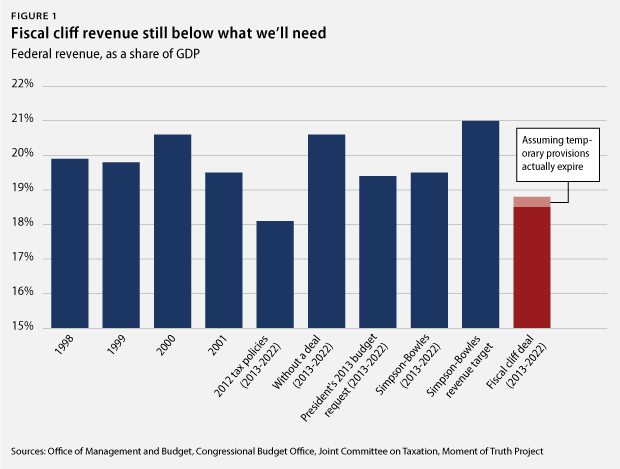

$617 billion is not an insubstantial amount, but given the enormous tax hole we’ve been in for the past decade, as well as our aging population and the projected increases in health care costs, it is far less than we will need for fiscal stability. Under the fiscal cliff deal, revenue will average about 18.8 percent of gross domestic product—the broadest measure of the country’s economic activity—over the next 10 years. That projection, however, assumes that the tax provisions that were only temporarily extended—such as the long list of business tax “extenders”—actually expire as the law says they will. If we instead assume that those tax breaks will continue to be extended each year, as they have been in recent history and were again in this deal, then revenue will average only 18.5 percent of GDP over the next 10 years.

Though revenue at that level is higher than it would be if we had just extended all the Bush tax cuts, it is still far lower than those proposed by several bipartisan budget plans. In their much-ballyhooed proposal, former Sen. Alan Simpson (R-WY) and former White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles, the chairmen of the president’s 2010 fiscal commission, recommended an average of 19.6 percent of GDP over the next 10 years, with an eventual target of 21 percent of GDP. And though it has received less attention, Alice Rivlin, the former budget director for President Bill Clinton, and former Sen. Pete Domenici (R-NM) also recommended a bipartisan plan for deficit reduction. Their plan generates a somewhat lower average of 19.1 percent of GDP over the 10-year period, but it actually reaches higher levels of revenue than the Simpson-Bowles plan does by the end of the decade.

Both bipartisan plans agree that we’ll need more revenue than 18.5 percent or 18.8 percent of GDP to substantially close the budget deficit, let alone balance the budget. In fact, the last time we actually balanced the budget—from 1998 to 2001—revenue surpassed 19.5 percent every year, averaged 20 percent of GDP those four years, and topped out at 20.6 percent of GDP in 2001. And that was before the Baby Boom generation began to retire.

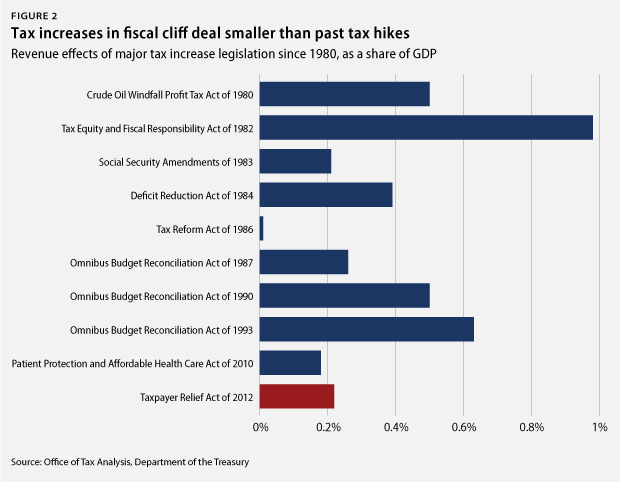

Of course, any new revenue is a step in the right direction. For more than a decade, the federal government has been drowning in red ink, in large part because of near-constant tax cuts. But no one should pretend the fiscal cliff deal is an enormous tax increase. Over the next four years, the overall tax increase resulting from this deal will amount to approximately 0.2 percent of GDP. The tax increases under President Clinton in 1993, by comparison, were about three times as large, surpassing 0.6 percent of GDP. In fact, President Ronald Reagan signed no less than four separate tax increases into law that were equal to or larger than yesterday’s fiscal cliff deal.

The fiscal cliff deal was a good start, and more than $600 billion in new revenue is nothing to sneeze at. But after more than a decade of repeated tax cuts, it will not be enough to put the federal ledger back onto a strong foundation. More will have to be done to ensure that we have adequate revenues to pay for the public protections, investments, services, and benefits that the American people demand and deserve from their government.

Michael Linden is the Director of Tax and Budget Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Ettlinger is Vice President of Economic Policy at the Center.