The decline of the U.S. middle class has corporate America and Wall Street scared. And nobody is more frightened than America’s biggest retailers.

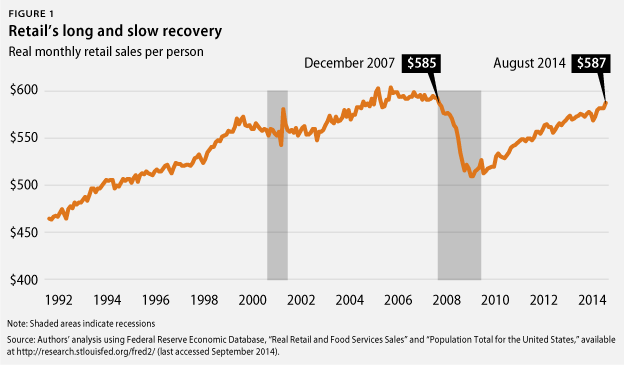

Five years after the 2001 recession ended, real retail spending per person had climbed 7 percent above its prerecession level. More than five years after the end of the Great Recession—August 2014—retail spending per person had finally reached its prerecession level.

Former Walmart U.S. CEO Bill Simon, whose company had seen consumer traffic drop for six straight quarters and same-store sales drop for five quarters, explained in July 2014 that “we’ve reached a point where it’s not getting any better but it’s not getting any worse—at least for the middle (class) and down.” Kip Tindell, CEO of the Container Store, put retailers’ feelings best when he said, “consistent with so many of our fellow retailers, we are experiencing a retail ‘funk.'”

The culprit is obvious: low wage and income growth for the middle class. Median household income in 2013 stood 8 percentage points below its 2007 prerecession level. The simple fact of the matter is that when households do not have money, retailers do not have customers. The failure of incomes to keep up with the growing cost of college, child care, and other middle-class staples leaves even less money for retail spending. A previous analysis by the Center for American Progress shows that this so-called “middle-class squeeze”—stagnant incomes and the growing cost of middle-class security—leaves the median married couple with two kids with $5,500 less to spend annually on food, clothes, and other essentials that retailers sell.

Or, as officials of J.C. Penney—whose sales fell 9 percent in 2013—put it when listing the risks to its stock value: “the moderate income consumer, which is our core customer, has been under economic pressure for the past several years.” Moreover, retail spending—which includes spending on everything from clothing to groceries to dining out—has broad implications for the entire economy since it accounts for a large fraction of consumer spending, which itself makes up 70 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, or GDP.

This report gathers new evidence to show that middle-class weakness and stagnant wage growth are holding the economy back. We use the financial statements, known as 10-Ks—the annual report required by the Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC—of the top 100 retailers in America and words of some of Wall Street’s top economists to underscore the point.

Time and again, America’s leading corporations warn investors that “decreased levels of consumer spending” (Kohl’s), “a renewed decline in consumer-spending levels” (Sears), and “decreased salaries and wages” (Burger King) could have a huge negative impact on their financial performance. The corporate consensus is clear: It is this cycle of stagnation—low wages, leading to weak demand, leading to slow growth, leading back to low wages—that is hurting companies, their consumers, and the U.S. economy at large.

This report finds that:

- Eighty-eight percent of the top 100 U.S. retailers cite weak consumer spending as a risk factor to their stock price.

- Sixty-eight percent of the top 100 U.S. retailers cite falling or flat incomes as risks. Looking just at companies that were publicly held in 2006, the percent listing consumers’ incomes as a risk factor has doubled since that year. A majority of retailers—57 percent—cite rising energy, health care, housing, and other essential costs as risks, showing the middle-class squeeze of rising costs and stagnant incomes.

- Wall Street economists are even more explicit about the risk that low wages pose to the economy, arguing that they drive low demand and high unemployment.

- Retailers could improve their profits by embracing a middle-class-growth-oriented agenda instead of spending their political energy on preventing policies that increase wages. Policies such as a minimum-wage increase could provide the perfect mechanism for coordinating wage growth that could benefit the entire retail sector by fueling more consumer spending.

The evidence assembled in this report directly repudiates “trickle-down economics”—the idea that the only way to produce economic growth is to redistribute money to the rich, who will create jobs for everyone else. Conservative politicians, lobbyists, and commentators may still be stuck in the trickle-down mindset of the 1980s, but corporate America and the Wall Street analysts who closely follow it know better.

While it may at first seem obvious that low consumer demand impedes growth, conservative think tanks and other believers in trickle-down economics ignore the evidence. Stephen Moore, chief economist at the Heritage Foundation, approvingly quotes Arthur Laffer, the father of trickle-down economics, who said, “All economic problems are about removing impediments to supply, not demand.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s “Jobs, Growth, and Opportunity Agenda” report similarly focuses on “expanding trade, producing more domestic energy, improving infrastructure, modernizing the regulatory process, making essential changes to entitlements, fixing the flaws in Obamacare, curbing lawsuit abuse, and advancing American innovation by protecting intellectual property…revitalizing capital markets, passing immigration reform, and improving education and training, which will expand opportunity, address inequality, and create jobs.” At the same time, it opposes any measures “that would automatically increase labor costs.” There is literally no policy in the agenda focused on immediately increasing aggregate demand and consumer spending other than perhaps the jobs created by infrastructure improvements and higher wages produced by immigration reform.

If the Heritage Foundation, the U.S. Chamber, and other proponents of trickle-down economics refuse to believe the overwhelming academic evidence that clearly shows low consumer spending and income growth are holding the economy back, they should listen to corporate America and Wall Street when they say that a consumer base with large, growing discretionary incomes—in other words, a strong middle class—is the vital ingredient for job growth and a strong economy. Or, as Ellen Zentner, executive director and senior economist at Morgan Stanley, explained, “faster employment and wage growth for those at the bottom, were it to have staying power, would help lift consumer spending, the biggest part of the economy.”

Brendan V. Duke is a Policy Analyst with the Middle-Out Economics project at the Center for American Progress. Ike Lee was an intern with the Economic Policy team at the Center.