Introduction and summary

In a period of nonstop fear, loss, and pain, there they were: female leaders around the globe, stepping up and making headlines as the new faces of crisis management.

In the United States, in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police, they were Black women mayors: San Francisco Mayor London Breed (D), Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot (D), Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms (D), and Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser (D). Overseas, they were female heads of state, winning international accolades for their deft handling of the coronavirus crisis: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand, who lifted the country’s lockdown and celebrated the eradication of the disease in her nation as American deaths from COVID-19 passed the 100,000 benchmark;1 Mette Frederiksen and Erna Solberg, the female prime ministers of Denmark and Norway, respectively, who were celebrated for the speed and efficiency with which they had shut down their countries and cared for their people;2 and Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, who was so successful in imposing fast and effective disease-containment measures that her country was widely hailed as a COVID-19 “success story.”3

News reports repeatedly flagged the down-to-earth empathy and efficiency of these and other female leaders whose nations had exceptionally low coronavirus fatality rates, contrasting their successes with the dismal records of reality-fleeing “strongmen”4 such as Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.5 Meanwhile, back in the United States, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D) was lauded for similar brass-tacks leadership. “We are just going to have to put our heads down and do what we have to do here in Michigan,” she said in an unusually glowing New York Times Magazine feature.6

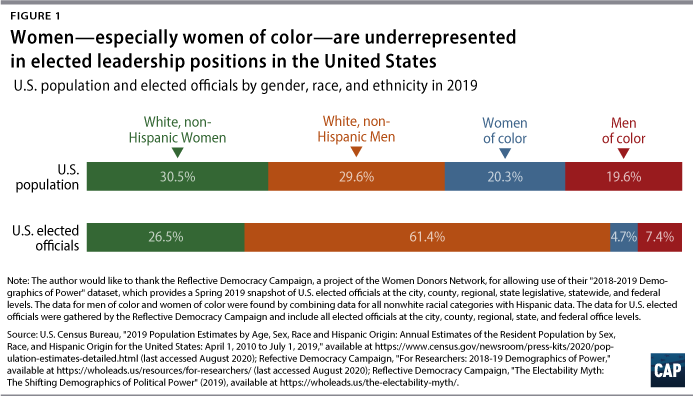

In this climate, the dearth of female elected leaders in the United States is all the more striking. And the persistent debates about women’s so-called electability—based as it is upon assumptions about their lack of appeal—is all the more strange.

There is a very serious disconnect between the way that political pundits talk about electability in the United States and the way the voting public thinks. While the former, as Amy Levin and Nicole Fossier of the Benenson Strategy Group wrote last year, typically build a case around “gendered code word” notions such as “likeability” and “hypothetical beers,” the latter, their 2019 survey of 800 likely voters found, favors candidates who have “a deep understanding of the challenges Americans face,” show “a strong debate performance,” and have “many well-thought out policies.”7 The electability conversation also tends to treat women’s political success as an eventuality, whereas the facts on the ground show that it’s already here.

The long-standing gap between women and men’s representation in U.S. political office—and the overwhelming financial and electoral advantages conferred by incumbency—mean that the aggregate numbers have been very slow to change. (In 2019, 69 percent of incumbents were men; at least 90 percent of incumbents typically win reelection.8) But large bodies of data, compiled over multiple election cycles, consistently show that when women run, they win.9

In 2017, the Center for American Progress published a report10 that pushed back on the popular notion that there was either something about women (i.e., their lack of electability) or something about American voters (i.e., overwhelming sexism) that was keeping women out of political office. The report argued instead that the real culprit was political gatekeeping—the structural factors that create a barrier to entry for any potential candidate who isn’t white, male, wealthy, and well connected. And it contained highly detailed recommendations for how those structures could change.

This report, which is based upon a year of interviews with political candidates, elected officials, campaign professionals, and other operatives working both within and outside of traditional power structures, builds on that earlier work. It argues that while considerable change is coming from the ground up, there is still a significant top-down roadblock keeping American voters from perceiving—and then endorsing—women’s very real political accomplishments. That blockage is due in large part to a failure of imagination, propagated by a political pundit class that uses its platform, time and again, to promote a discussion of women’s electability, or lack thereof, which makes women’s political underperformance a fait accompli.

That long-standing conversation has to change. Public awareness of women’s potential for electoral success in the United States needs to catch up to the reality of women’s actual victories in recent elections and their track records of significant leadership once elected. And, for that to happen, the focus of the national conversation has to shift from who women are—and what’s wrong with them—to what women have done and must do again.

This report demonstrates that electability today is not so much about being a certain kind of person—white, male, monied, and politically connected—but rather about running a certain kind of campaign. Electability, as successful U.S. politicians have shown in the past few years, isn’t about candidates convincing voters that they can conform to standard ideas about what power looks and sounds like. On the contrary, it’s about demonstrating that they’ll show up as they are and meet voters where they are. Specifically, it’s about getting in front of voters, listening to voters, and getting voters to show up to the polls. Increasingly, this has meant making sure that it’s possible for voters to vote—a challenge that has only become more acute during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That winning strategy—which has had the added benefit of broadening access to our democracy for those who traditionally have been outsiders—offers plenty of opportunities for policymakers, advocates, and activists to lend support. And the need for that support is now urgent. Concretely, this means:

- Pushing back against restrictions aimed at limiting the American right to vote—measures that are disproportionately aimed at people of color and young potential voters.

- Fighting Election Day voter suppression in all its forms.

- Passing legislation to guarantee the greatest possible degree of ballot access, whether remote or in person, with sufficient funding for high-quality poll worker training, reliable voting equipment, widely disseminated public information, language support, and measures to ensure that people with disabilities or who live in locations such as tribal lands can easily exercise their right to vote.

- Taking on the structural barriers that have long impeded women, and women of color above all, from making their way onto ballots.

As Levin and Fossier wrote in 2019, the “conventional wisdom” about female candidates has consistently worked against women in the past.11 All that’s needed to change that now is a focus on the facts.

Women have a record of success in U.S. elections—despite false narratives

The United States has long been a global laggard when it comes to women’s political representation. In 2019, the United States ranked 86th out of 152 nations for women’s political empowerment in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report.12 Part of the reason for this is that the main tactic other countries have used to quickly increase their share of female lawmakers—numerical quotas—does not appear to be legally or culturally acceptable in the United States; American courts have in the past rejected the use of race- or gender-based numerical quotas as unconstitutional,13 and there is a widespread belief that the use of government-mandated numerical requirements is “un-American.”14 (Both major political parties employ internal quotas to guarantee gender parity, however. The Republican National Committee is made up of one man and one woman from each state and territory, and the Democratic Party requires an even male-female split among its convention delegates.15)

The fact that voters select candidates directly through a primary system—rather than choosing from a slate chosen by party leaders, as is the case in many of our peer nations—has led to a common perception that the United States’ lack of gender parity reflects the will of the people. American voters, it’s often said, just aren’t ready for female leaders, who have proven their so-called unelectability in a number of presidential elections. The extremely small sample of female candidates who have contended for the U.S. presidency and vice presidency make drawing generalizations problematic at best, however. Large bodies of research tell a very different story.

Last year, when the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University made an apples-to-apples comparison of the rates at which nonincumbent men and women won their 2018 primaries and general election races for the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, governorships, and other statewide elected executive seats, they found that the women did better than the men across all levels of office.16 And when the Reflective Democracy Campaign, a project of the Women Donors Network, analyzed the outcomes of thousands of 2018 races at the federal, state, and local level, they found that white men were actually the only demographic group to have underperformed relative to their proportion in the candidate pool.17 A Rutgers study published in early July 2020 of nonincumbent candidates in congressional primaries showed a steady continuation of that pattern of female candidate overperformance: By early July, 44.4 percent of Democratic women and 37.8 percent of Republican women had won their primaries, compared with just 19.9 percent of nonincumbent Democratic men and 22.5 percent of nonincumbent Republican men.

The political fortunes of Democratic and Republican women have not improved in tandem in recent years. In 2019, 39 percent of Democratic elected officials nationwide were women, compared with just 27 percent of elected Republicans—an imbalance that held up at the local, state, and federal level.18 There are a number of reasons for this—chief among them the fact that political organizing aimed specifically at increasing women’s representation has been much more established for far longer among Democrats, whose voters also tend to be more likely than Republican voters to say they believe there should be more women in office.19

But that gap may well shrink this year. In 2018, Democratic women comprised 32.5 percent of all candidates for the U.S. House and 42.4 percent of all nominees (i.e., those who won their primaries), according to an analysis by the Center for American Women and Politics. In contrast, Republican women made up 13.7 percent of all U.S. House candidates that year and only 13.2 percent of all nominees. By early August 2020, however, the gap in both the numbers of candidates and in the primary success rates for Democratic and Republican women had notably decreased: Democratic women made up 37.8 percent of all U.S. House candidates and 47.5 percent of all nominees, while Republican women comprised 21.2 percent of all U.S. House candidates and fully 21.8 percent of all nominees.20 At base, experts note, the essential problem holding back women of both parties has long been the same: They’re running against long-standing networks of powerful gatekeepers—party and elected officials, big donors, unions, campaign operatives, consultants, and advocacy groups. These gatekeepers have traditionally recruited and groomed candidates; screened them for viability—their ability to raise large sums of money—and paved the way for them to a slot on the ballot through fundraising, introductions to power brokers, and campaign support. These gatekeeper systems have greatly disadvantaged newcomers, people without independent wealth or wealthy social connections, and people who do not have the flexibility to drop all else in their lives to play the political game as it’s always been played. In other words, these systems have disadvantaged regular working people as well as women—and women of color above all.

In recent years, however, there have been signs that this gatekeeper system is being seriously challenged in ways that will undoubtedly continue in upcoming election cycles. Most notably, in 2017 and 2018, an upsurge of highly energized grassroots supporters turned out at historic levels to canvass, educate, and bring voters to the polls to elect the kinds of nontraditional candidates whom gatekeepers have long overlooked or even discouraged from running. Their efforts helped bring an exciting new wave of women to every level of elected office in the United States. And despite the very real limitations of campaigning amid the COVID-19 pandemic, their efforts continue today.

The unprecedented, large, and victorious crew of newcomers who pushed women’s representation—and the representation of women of color most dramatically—to record highs in Congress in 2018 were notable outsiders who broke all sorts of rules about who American voters are supposed to find acceptable. The new female stars of Congress ran the gamut in breaking rules about who is supposed to run and how, when, and where they’re meant to do so.

These were candidates who, in defiance of all the old wisdom, often looked nothing like—or had nothing in common with—the communities of voters who elected them.21 For example, Rep. Lauren Underwood (D), an African American nurse, ran in a rural suburban Illinois congressional district with fewer than 3 percent Black voters.22 Rep. Sharice Davids (D), an open lesbian, Native American, and former mixed martial arts fighter, won her seat in a more than 81 percent white district of Kansas.23 They didn’t wait their turn to run, ceding their ambitions to the will of party gatekeepers. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), for example, mounted a primary challenge against a 10-term white male incumbent so powerfully entrenched that he was known as the “King of Queens,”24 and Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D), the first woman of color ever elected to the Boston City Council, won her way onto Massachusetts’ formerly all-white congressional delegation by beating an incumbent backed by the party establishment, including the political arm of the Congressional Black Caucus.25

None of these new congressional stars had the trappings of wealth, power, and social connections normally associated with political viability in the United States—nor did they have decades of inside-the-Beltway knowledge and relationships. But what the upset victors of 2016 and 2018 did have was an enormous ability to successfully mobilize the enthusiasm—and in some cases, the rage—of their supporters. In doing so, they introduced a whole new way of thinking about what being electable really means.

Their political fortunes have been closely watched by advocates who want to keep women’s numbers on the rise on both sides of the aisle. A new unwillingness to defer to party gatekeepers—and, as far as women’s representation is concerned, “let the chips fall where they may,” as the Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson put it in 201826—has translated into a significant increase in GOP PACs aimed at increasing the number of women in office. Some examples include Republican Women for Progress, Winning For Women, Right Women, Right Now, and the Value in Electing Women PAC. “We’re in a totally different environment than we’ve ever been in in terms of interest in bringing different voices to the party,” a longtime Republican strategist said in an interview for this report. Whereas formerly, she explained, candidates had no choice but to work their way up through the “pecking order,” asking “permission” to run from local county chairs, precinct chairs, and other officials in the party hierarchy, she’s seen “a real disruption” in the post-2016 period. “No one feels like now they have to ask for permission,” she said. “I’m not saying you don’t [do] outreach to them and cultivate relationships,” she added, referring to party gatekeepers, “but if you’re going to run or not does not really hinge on if they’re going to bless your campaign. There’s a freedom in that.”

Electability in a polarized age

Rachel Bitecofer, a political scientist at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, has built up a brand by delivering election predictions that shock establishment forecasters. In 2017, she predicted a Democratic landslide in the long Republican-dominated Virginia House of Delegates; the Democrats did, indeed, pick up 15 seats that year, 11 of which were won by women. In July 2018, with other forecasters anticipating only “modest” gains for the party out of power in Congress, she predicted that the Democrats would pick up a massive 42 seats in the U.S, House of Representatives; Democrats gained 41.27 Her predictions, she explained, in an interview for this report, depart from conventional wisdom in that her focus isn’t really on the characteristics of individual candidates. They rest instead on a specific understanding of the collective psychology of American voters and one aspect of the voter psyche above all: In our highly polarized climate, she believes, the single most salient factor—often the only factor—driving voter choice is party affiliation. The candidates who pulled off surprise wins in 2016, 2017, and 2018, she notes, got voters—particularly voters who felt ignored in the past—really, really excited. Newcomers, particularly in legislative elections where personal contact is all-important, shot to victory when they were able to inspire their supporters to organize, mobilize their neighbors, and turn out en masse—achieving a such a critical mass, in fact, that the privileges of incumbency couldn’t withstand it.

Sensing that kind of excitement in her home state of Virginia is what allowed Bitecofer to make her off-the-wall-seeming call about the Democrats’ historic gains in the Richmond statehouse in 2017.28 (A race in which, Rutgers University political scientist Kelly Dittmar has noted, women candidates were 56 percent of all challengers but 75 percent of all successful challengers.29) Generalizing her formula for translating voter passion into accurate expectations of voter turnout allowed her to make surprisingly precise predictions for the U.S. House in 2018. The Democrats’ decisive midterm losses in 2010 and 2014, on the other hand, she says, came because the party’s voters were feeling satisfied, if not complacent, and turnout was down, while Republican motivation to get out and fight back was up.30

That’s why, Bitecofer believes, discussions about electability based on a candidate’s gender—or race—consistently miss the mark. Indeed, the entire debate about women’s electability is “completely outdated,” she said. “This conception of electability is based upon concepts that are from the pre-polarized era … In the old days of the old electorate, where the parties were ideologically heterogeneous, when you had conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans, you might have been able to make a convincing argument that factors like skin color or gender might be something that could potentially tip the scales,” she continued. But today, she said, “the power of these physical characteristics is lessened because of the heightened importance of partisanship. Because what matters to voters more than anything in this polarized era is, ‘Is this individual on my team? In my tribe?’ Man, woman, Morman, child molester, whatever, if they’re on my ‘team’ in this polarized era, my probability of voting for them is pretty good.”

Bitecofer’s message echoes the findings of a wide body of other research indicating a need to update our national conversation about women’s electability for changing times. For one thing, large-scale polling has consistently shown that American attitudes about gender and power have vastly altered over the past few decades. In 2018, the General Social Survey found that only about 13 percent of Americans said they believed that women were less well-suited emotionally for politics than men, compared with almost 50 percent in 1975.31 In 2018 as well, a solid majority—59 percent—of Americans told the Pew Research Center that there were too few women in high political office. Although adherence to that belief varied considerably by party, with 79 percent of those who vote or lean Democratic in agreement, compared with just 33 percent of those who vote or lean Republican. 32

At the same time, a growing number of academic studies dating back to the late Obama years have shown that no matter what voters’ attitudes about gender happen to be, a candidate’s sex just isn’t a terribly salient factor in voter decision-making anymore.33 A number of academics who have studied how American women fare at the ballot box have concluded, over the past few election cycles, that when it comes to legislative elections, gender bias on the part of voters or even in the media does not play a definitive role in the outcomes of specific races.34 There’s a difference, they’ve found, between the attitudes that people express in the abstract—when they’re answering researchers’ questions, for example—and when they’re faced with real-life choices in the voting booth. In the latter scenario, they’ve found that, time and time again, abstract beliefs about men and women don’t carry much weight. What really matters is a candidate’s party and ideology.35 As a result, voter turnout is the single most important factor in electability—for all people, and especially for newcomers or outsiders (as women tend to be) who are going against the grain and trying to flip districts or otherwise shake up the political status quo.

Getting out in front of voters—and getting voters to show up

Although there is no good data to indicate that the presence of women on the ballot increases voter turnout—what studies exist are contradictory,36 and more research is needed—there are plenty of examples from recent elections that show that voter mobilization, or lack thereof, played an absolutely essential role in female candidates’ political fortunes. The lack of Democratic turnout in a number of swing states, many now believe, was a big part of what lay behind Hillary Clinton’s surprise loss in the presidential election of 2016. In Wisconsin, for example, the Clinton campaign’s failure to invest in field operations and get out the vote in Black communities—combined with restrictions and confusion occasioned by new voter ID laws and the lack of President Barack Obama’s highly motivating presence on the ballot—contributed to a 25.5 percent drop in Black voter turnout. Together, these factors led to Clinton’s defeat by a less than 1 percent state margin.37 The dramatic wins for women in 2018, on the other hand, played out in a landscape of historically high Democratic voter turnout.38 Ilhan Omar (D), the first Somali-American and one of the first two Muslim women elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, won her Minneapolis primary in Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District thanks in part to record voter turnout in her district.39 And, in perhaps the most dramatic example, Stacey Abrams, a Black woman running for governor in the longtime deep-red Southern state of Georgia, won more votes than any Democrat in a statewide race had ever done before,40 losing her race by a mere 1.4 percent.41

Abrams and her allies had invested greatly in voter engagement over the course of her 11 years in the Georgia statehouse, registering more than 200,000 voters, many of them young or from the communities of color that now make up approximately 40 percent of Georgia’s population.42 And she had inspired massive voter turnout: Fully 55 percent of eligible voters participated in her race—a rate 21 points higher than the state’s average between 1982 and 2014, according to a postelection analysis by FiveThirtyEight.43

In interviews for this report, former Abrams campaign officials said that it was Abrams’ decision to find new voters, register them, and then speak directly to them via field offices, door-to-door canvassing, targeted talk-radio ads, and meet and greets in Costco parking lots, among other efforts—rather than just big, expensive media buys aimed at suburban white voters—that brought her this enormous voter engagement. It’s what took Abrams from unelectable status—in the minds of the Atlanta political elite and, early on, national gatekeepers as well—to a historic showing of support from Democrats in Georgia of all ages and races, blue-collar union members, immigrants, and suburban whites, too. In addition, the campaign aimed early on to vastly boost engagement and turnout by people whom campaigns normally overlook—the young people and people of color who tend to participate in lower levels in elections and are written off as irregular voters by traditional campaign professionals, who tend to focus instead on ostensibly persuadable swing voters, who skew whiter, older, and more suburban, and who tend to vote more frequently.

The math was better, explained Lauren Groh-Wargo, Abrams’ 2018 campaign director, in a strategy memo written for top Democrats and obtained by the Associated Press last year. In Georgia, she noted, the number of “persuadable” swing voters pales in comparison to the number of “potential” voters—“new registrants plus infrequent/nonvoting Democratic-leaning voters,” who tend overwhelmingly to be young and/or people of color. At the outset of the 2018 gubernatorial race, she wrote, Georgia had about 150,000 “persuadable” voters compared with about 1.7 million “potential” voters; by the time of the general election, thanks to vast new registration efforts aimed at those groups, the latter number had swelled to 1.9 million.44 But, she said in an interview for this report, it wasn’t an either-or choice. It was a matter of getting Abrams out into communities—letting them see a woman who hadn’t sacrificed her authenticity to become polished and perfect (as per the vision of white, D.C. consultants). It was also a question of putting on display Abrams’ unmistakably masterful grasp both of policy and the needs of the people of her state—and also making sure that voters were aware of her wide range of early endorsements both from national progressive groups such as EMILY’s List and from state and local organizations such as the mostly white, male Building Trades Unions.

“Here’s my shorthand on ‘electability,’” Groh-Wargo said in an interview for this report. “Voters can sniff out a fake … And voters are more similar than different in terms of what they want, and they want people who aren’t fake.” Around that basic principle—accomplished in campaign practice by simply getting a candidate out in front of voters as much as possible—“you can build a winning coalition,” she said. “We shouldn’t be fearful of candidates who are different. It can be a real position of strength. And just because they look one way or another doesn’t mean that they’re going to alienate folks who don’t look like them.”

Recommendations

In a deeply divided country, where many races—particularly on the state or local level—are decided by a mere handful of votes, a key component of electability has to be having access to fair, transparent, and credible elections in which every single vote is counted. Voting access and election transparency are not just matters of basic civil rights; they are also key components of increasing women’s political representation.

In 2018, Political Parity reported that states that have “more open voting procedures—same-day registration, automatic registration when issuing drivers licenses, mail-in ballots, simplified early voting procedures, or longer early voting periods—tend also to be states that support women’s candidates.”45 States with greater participation by African Americans and other voters of color, as well as young voters—all communities that have been the target of recent voter suppression efforts—also tended to have a greater share of women in Congress, an earlier Political Parity analysis showed.46 The same had previously been proven true for states that had “clean elections” with more open voting procedures.47 New Mexico, which sent its first Native American congresswoman to Washington in 2018, and Massachusetts, home to Rep. Pressley, are both states with voting systems known to be strong in promoting transparency; Georgia is not.48

Guarantee voting access and ensure election transparency

The United States needs robust policies to fight voter suppression such as same-day registration, automatic registration, online registration, longer early voting periods, pre-registration for 16- and 17-year-olds, and no-excuse absentee voting. Conducting elections with strong voter-verified paper ballot records and robust postelection audits are also necessary for ensuring accuracy in election outcomes.49

The United States must also have laws in place that guarantee that all eligible Americans can exercise their right to vote. Measures that aim to limit who can vote and how much certain votes are worth—such as strict voter ID requirements, the disenfranchisement of felons, discriminatory signature matching requirements, mass voter roll purges, and improper gerrymandering—must be overturned. Local law enforcement must be enlisted to protect voters from physical and verbal harassment on and around Election Day.

The government must also provide accurate and timely information to voters about where and when they should vote as well as what documentation they need to bring with them. Policymakers must ensure that voters living on tribal lands as well as those for whom English is a second language are fully empowered to participate in U.S. elections. This is a particular problem for many Asian American and Hispanic communities. The Voting Rights Act stipulates that some jurisdictions must provide language assistance at the polls, yet a 2016 survey showed that 1 in 6 Latino respondents said that a “lack of Spanish-language assistance or materials” was a barrier to voting.50 In addition, policymakers must address the factors—including challenges from voter ID laws, difficulties in finding accurate election information and accessing polling places, and a lack of sufficient poll worker training in the specific needs of people with disabilities—which depress voter turnout in the disability community. In 2017, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that 60 percent of polling places surveyed had potential impediments for disabled voters—a problem that has not improved in the election cycles since.51 Lawmakers must ensure, with funding, increased access to polling places for people with disabilities, accompanied by measures to make sure that information related to voter registration, notices regarding voter roll purges, and instructions for voting early, remotely, or at the polls on Election Day can successfully reach them. Policymakers also need to guarantee that poll workers are sufficiently trained so that they can answer questions, deal with technical issues, and keep voting lines moving as efficiently as possible.52

Equally important: When polling stations are open for business, they must be equipped to serve voters, with fully functional voting machines and adequate staff to operate them and manage crowd overflow. Stories of voters braving bad weather and putting in the time to stand in line for hours in order to vote are heroic and inspiring—but they shouldn’t have to exist at all. No voter in the United States should have to stand in line for more than 30 minutes to participate in our democracy, the bipartisan Presidential Commission on Election Administration concluded back in 2014. That message needs to be heard—and made into reality—even more urgently today.53

Election officials need to both monitor polling station performance during voting and evaluate it after in order to anticipate problems and look for bottlenecks and glitches so as to prevent them from reoccurring in the future. All voting equipment in the United States must be verified before Election Day to diagnose and rule out software and security issues.

Increase vigilance for open, safe, and transparent elections during the pandemic

The wretched experiences of voters who stood in line for hours to cast their ballots in the Wisconsin and Georgia primaries this past April and June show that problems around access and transparency have in no way been ameliorated. Instead, the health safety measures posed by the coronavirus crisis have made all these issues far more acute. Voter suppression remains a huge threat to our democracy, and the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to disrupt our already fragile and embattled voting process like never before.54 Making sure that every American is able to vote under safe, secure, and transparent conditions has to be our country’s number one priority as we head into the November 2020 elections.

Several recent Center for American Progress reports lay out detailed proposals for ensuring ballot access and election transparency during a national public health emergency.55 CAP’s recommendations, which are detailed in a joint publication with the NAACP, titled “In Expanding Vote by Mail, States Must Maintain In-Person Voting Options During the Coronavirus Pandemic,”56 include:

- Expanded opportunities for voter registration and widely available same-day registration to ensure that Americans can add their names to voter rolls and cast ballots that count. Same-day voter registration allows voters to register and cast their ballots at the same time and has been shown to increase voter participation. These measures are urgently needed this year, as typical in-person registration drives have been canceled due to social-distancing mandates. Many Americans are likely to miss pre-Election Day registration deadlines due to postal delays or processing delays caused by decreased personnel.

- At least two weeks of in-person early voting options to prevent crowded polling places and long lines on Election Day by dispersing voters across several days.

- Expanded opportunities for voting by mail with ballot-tracking measures to ensure votes are counted. In a year when mail-in voting is sure to be a necessity, CAP has previously recommended that states using mail-in ballots put in place robust ballot-tracking programs that allow voters to follow their ballots through every step of the voting process and to fix any issues that may arise with their voted ballots so that mistakes are caught before certification.

- Elimination of discriminatory signature verification requirements so that ballots cast by eligible voters are not improperly discarded. Without strong protections in place, signature matching processes can result in valid ballots being thrown away for subjective reasons. In the past, this has disproportionately affected voters of color, people with disabilities, young and aging Americans, and people for whom English is a second language.

- Elimination of overly burdensome requirements for absentee ballots such as requiring ballots be signed by witnesses or notary publics or that ballots be postmarked and/or returned before Election Day. Such requirements are unnecessary and overly burdensome, particularly during a public health crisis.

- Robust voter education to ensure Americans know how to register to vote and cast ballots this year. Many jurisdictions are altering election procedures this year to contend with the coronavirus pandemic and will need to inform voters of these changes to prevent widespread confusion.

Expand opportunities to vote by mail—but don’t close the polls

The health restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic have made clear the urgent need to provide Americans with vastly expanded opportunities to vote by mail. And yet, as CAP and the NAACP argue,57 policymakers must not allow robust mail-in voting to be used as a reason to temporarily close or eliminate in-person polling places. The elimination of in-person voting options will result in the inadvertent disenfranchisement of countless Americans, including voters with disabilities, American Indian and Alaska Native voters, African American voters, and those who need to make use of same-day voter registration. Jurisdictions must, at minimum, maintain their pre-pandemic polling place numbers or, in some cases, increase the number of polling places available to prevent long lines and promote social distancing. There are ways to keep the polls open while preserving public health through social distancing such as providing proper training for election workers on sanitizing equipment and social distancing. Each polling place should be equipped with adequate provision of sanitary supplies such as masks, gloves, and cleaning equipment.

Enact policies to open up opportunities on the ballot and get women in front of voters

When women run, women win. But first, they have to work their way through or around political gatekeepers to get on the ballot.

Both the Democratic and Republican parties need to systematically rethink how they identify, recruit, and support new candidates, urging them to set voluntary numerical goals to increase their recruitment of women. They need to pass campaign finance reform measures that include options for public financing to level the playing field for less moneyed candidates, as women often are. (States that already have public financing for their legislative elections all have greater numbers of women serving in office.) For the same reason, elected offices must consistently pay a living wage, creating opportunity for candidates who are not independently wealthy or supported by a high-earning partner.

There must also be greater child care support for candidates—a demand that was at least partially answered in May 2018, when the Federal Elections Commission approved a petition by the congressional candidate Liuba Grechen Shirley to report child care as a campaign expense. In the wake of that groundbreaking decision, eight other candidates for Congress reported babysitting and child care as campaign expenses,58 and a number of states are now considering similar legislation, adding to the handful that already have it on the books; they include Utah, which made news in 2019 when its Republican-controlled state legislature passed a gender-neutral child care campaign expense bill that was introduced by a Republican state legislator, Craig Hall.59

Another piece of heartening news in recent years is that all around the country, progressive activists have increasingly taken the mechanics of electoral politics into their own hands. They’ve formed a wide web of grassroots and national groups that are now recruiting and supporting nontraditional candidates—often women—whom gatekeepers still often overlook. They’ve provided training and field workers, small-donor fundraising, campaign consulting, website design, social media management, and issue research—all for free. In so doing, they’ve not only greatly diversified the field of candidates running for office, but they’re also bringing the start of some much-needed diversity to the people behind the scenes in politics, working as consultants, campaign managers, and strategists. All of the groups struggle for funding, even with the energy of a charged political landscape behind them. It remains to be seen whether that struggle will intensify or lessen after the presidential results of 2020.

Conclusion

In the current, passionately radicalized political era in the United States, the perennial pundit-class conversation about women’s electability is due for a major reboot.

Women’s political success is a fact—not an aspiration. That’s why, when it comes to thinking about and, more importantly, rectifying the gender imbalance in American politics, the electability conversation completely misses the mark. It’s a relic that rests upon outdated assumptions about both American voters and American women candidates. It’s backward-looking, reinforcing and reifying stereotypes that voters, left to their own devices, seem more than ready to leave behind.

It may well in fact be that the popular conversation about female candidates’ electability has itself become a barrier to women’s political progress. The idea that women are unelectable is not just a myth but a potentially dangerous one at that because it can have an outsize effect on shaping voter perceptions of female candidates’ potential.

Both perceptions and reality, however, can and will change. As Christina Reynolds, the former deputy communications director of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign and a current vice president at EMILY’s List wryly put it in an interview for this report, our certainties about the American electorate are rock-solid—until they’re not. In her words, “They’ won’t elect a woman … until a woman is elected.”60

About the author

Judith Warner is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and the author, most recently, of And Then They Stopped Talking to Me: Making Sense of Middle School. Her previous books include the New York Times bestsellers, Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety and Hillary Clinton: The Inside Story, plus the multiple award-winning We’ve Got Issues: Children and Parents in the Age of Medication. Her most recent work has focused on identifying and dismantling the barriers that prevent nontraditional candidates—women, people of color, young people, the nonwealthy, and LGBTQ candidates—from increasing their representation in elected office.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editing this report was a pleasure due to the kind support of my colleagues on the Women’s Initiative, the Art and Editorial teams, and other teams at CAP who contributed their time and insights. I am particularly indebted to Shilpa Phadke, Will Beaudouin, Tricia Woodcome, Jocelyn Frye, Diana Boesch, and Robin Bleiweis, as well as the many people who generously shared their knowledge with me in telephone interviews.