The legal educations and formative experiences of federal appellate judges are largely homogeneous as well, with approximately 30 percent of circuit court judges being educated at just four law schools: Columbia, Harvard, Stanford, and Yale. In addition, the prevalence of federal judicial clerkships, which can help young lawyers gain entry to powerful professional networks, is on the rise; younger members of the federal bench are much more likely than their older counterparts to have held a clerkship, with the most recently appointed appellate judges increasingly holding two or even three clerkships.

It is important to consider these statistics alongside the fact that the federal appellate bench remains overwhelmingly white and male and that these trends in career and educational backgrounds correspond with those professional pathways that white men have long been able to access without the discrimination women and people of color have faced. To underscore this point: Nearly 70 percent of all white men on the federal appellate bench spent their careers in private practice, but less than half of the only 12 women of color on the bench came from the same sector.

A shocking lack of professional diversity on the bench

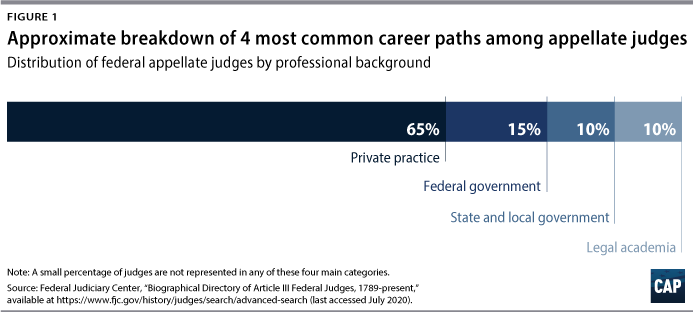

Only about 1 percent of sitting circuit court judges have spent the majority of their careers as public defenders or within a legal aid setting. Individuals from predominantly private practice and federal prosecutor backgrounds make up more than 70 percent of all appellate judges.

This lack of diversity not only reflects the closed and elitist nature of the federal appellate bench but also represents a barrier to the courts’ ability to develop intellectually rich jurisprudence grounded in an awareness of a broad set of individuals’ experiences across the country. To improve this state of affairs, significant disruptions are needed—from law school through every stage of an attorney’s prejudicial career—to broaden pathways to the federal bench and challenge long-held assumptions on the “right” type of attorney to take up a gavel.

In order to better understand the individuals who hold such positions of power, previous reports from the Center for American Progress have analyzed the demographic diversity of the federal judiciary in great depth.1 Perhaps unsurprisingly, despite some progress, those reports found that individuals on the federal bench look significantly different from those whose rights they rule on—particularly in regard to women of color and LGTBQ individuals.2 Those reports further found that President Donald Trump’s overwhelmingly white and male nominees to the federal judiciary have regressed efforts to diversify the bench that have occurred under previous administrations, both Democrat and Republican.3

This report builds on CAP’s earlier work by focusing on the career backgrounds of those judges sitting on the U.S. Courts of Appeals, with the goal of analyzing the educational and professional experiences that have significantly informed these judges’ understanding of the law. The lack of diversity on the bench in this regard is clear.

Disparities are stark

Nearly 70 percent of the 181 white men on the federal appellate bench spent their careers in private practice, but less than half of the only 12 women of color on the bench came from the same sector.

In addition, statistics on gender as well as race and ethnicity are presented alongside professional characteristics, as doing so demonstrates significant variances in the education and career trends among judges from different demographic groups.

Gender, race, and ethnicity are not, of course, the only measures of diversity. Regrettably, data on characteristics such as religion, disability, and LGBTQ status are not included in the Federal Judicial Center’s (FJC) database and, to ensure consistency of data, are not included in this report.

Other sources, however, indicate that diversity on the bench in these regards is significantly lacking. One 2017 study in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies found that approximately 45 percent of the bench identified as Protestant, 28 percent as Catholic, 19 percent as Jewish, and just 5 percent as Mormon. Hindu judges comprised less than 1 percent of circuit court judges, while no Muslim, Buddhist, or atheist judges were identified.4 In addition, there are very few openly LGBTQ appellate federal judges.5 Finally, indicating a significant need for more attention in this area, the author was unable to locate any public information on judges with disabilities. As previous reports from CAP have called for, the FJC should make significant efforts to improve the range of reported characteristics.

Gender, race, and ethnicity on the appellate bench

Of the 297 judgeships on the U.S. Courts of Appeals as of July 1, 2020, 77 appellate judges are women, of which 65 are white; 51 appellate judges are African American, Asian American, or Hispanic (the only communities of color represented on the federal appellate bench); 39 of the appellate judges of color are men; and there are only 12 women of color on the U.S. appellate bench—five African Americans, five Hispanic Americans, and two Asian Americans.

This report explores why professional diversity matters and provides an overview of the current federal appellate bench—first by exploring the educational backgrounds and clerkship experience of federal judges and then providing a deep dive into the professions represented on the bench. While the author discusses clerkships throughout this report given their growing prevalence among candidates for the bench, such discussion should not be confused with an endorsement of that credential as a prerequisite to becoming a judge. When relevant, this report also highlights notable differences in the educational and professional paths between the most senior and youngest members of the bench.

Finally, this report concludes with a discussion of reforms needed to ensure a professionally diverse bench, providing examples of how the legal profession, Congress, and future administrations could act to improve the bench. Importantly, the report notes that the lack of professional diversity is severe enough that all policymakers must take responsibility.

It is sobering to consider that a single federal judge, thanks to their lifetime appointment, can play a powerful role in defining the rights of individuals for decades. For example, one 9th Circuit Court senior judge was confirmed to his seat in 1971 after being appointed by President Richard Nixon—nearly 10 years before today’s 40-year-olds were born. By identifying what trends currently exist in judicial selections, policymakers and the courts can better understand how to ensure the judiciary can strengthen itself as a whole.

Methodology

The professional and demographic data presented in this report reflect federal judges appointed to Article III appellate courts as defined by the U.S. Constitution as of July 1, 2020. Unless cited otherwise, the data derive entirely from the FJC website, specifically the FJC’s Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789 to the present.6

The author made the decision to include all sitting judges in the scope of this report—meaning both active judges, who regularly hear cases and are employed full time by the federal judiciary, as well as senior judges, who have entered into semiretired status. The reason for this decision was twofold. First, and most importantly, the report’s aims to examine the full universe of judges who are still actively hearing and ruling on cases; many senior-status judges, despite the part-time nature of their work, still regularly issue decisions on both routine and major matters.7 In addition, by examining both active and senior judges, the author was able to identify differences in trends between those appointed to the bench in recent years compared with earlier administrations.

Gender, race, and ethnicity statistics

Previous reports from CAP have detailed a wide range of demographics on the bench—from racial and ethnic diversity to religion—within the U.S. district and circuit courts. This report does not attempt to overlay the same depth of analysis in that respect to the professional characteristics described below. It does, however, discuss disparities within professional tracks by breaking out statistics by gender and race. Particular attention is given to women of color, who are severely underrepresented on the bench, reflecting the long-standing intersectional discrimination these judges face.8

In order to ensure consistency, demographic categorizations are derived entirely from the FJC website. The author, however, wishes to stress an awareness that within these broad categories, a wide variety of communities who face different types of discrimination also exist.

Defining a career

Finally, it is important to explain how each judge was categorized. In contrast to other reports that, for example, chose to survey federal judges based on the position in which they served immediately before joining the bench9 or that identified judges based on characteristics such as partnership status at a firm,10 this report categorizes judges based on the field in which they spent the majority of their career before becoming a judge at any level, federal or state.

There are certainly advantages and disadvantages to defining the careers of judges in this manner. But while the field in which a lawyer spends the majority of their career may not demonstrate the full range of a lawyer’s professional experience and networks—or certainly their personal beliefs—this methodology does make clear the dominant setting in which the judge developed their expertise and insights into the law.

For a small but not insignificant number of appellate judges, careers were evenly split between two fields. In those cases, judges are counted in both career categories. Finally, it should be noted that many appellate judges served as adjunct professors at law schools before their appointments. Such experience, particularly because it was almost always paired with other full-time, significant employment, was not counted toward a judge’s overall total of years spent in legal academia.

At the offset, it is important to address why professional diversity matters, particularly given that lawyers throughout the profession have a wide variety of personal experiences and perspectives. Unfortunately, because the bench has been dominated for so long by those from a narrow range of backgrounds, it is difficult to broadly analyze the impact judges from more diverse professional backgrounds can have on American jurisprudence. But while some conservatives may grandstand and argue that judges should operate as complete blank slates in regard to interpreting the law11—negating the need for diversity of any sort on the bench—the reality is that judges, being human, bring unique perspectives into their decision-making. And many of those perspectives can be significantly shaped by professional experiences.

Of course, judges who spent their careers in certain fields do not vote as blocs. In the late-2019 5th Circuit Court ruling that largely declared the Affordable Care Act (ACA) unconstitutional, for example, all three judges sitting on the panel were from private practice backgrounds, and all were white. While two voted to overturn the ACA, one dissented.12

But the fact that such an important case—concerning issues that would most directly affect people who are economically struggling and often face significant structural racism13—was heard and decided by judges with such similar career backgrounds underscores just how homogeneous the appellate bench is today. It also begs the question of what nuance and insight a judge who had actually spent their career working within such communities could have brought to the bench when evaluating the cases brought before them.

But it is perhaps the legacies of jurists who dedicated significant amounts of their careers to nonprofit service that best illustrate the importance of professional diversity.14 Most famously, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall spent almost the entirety of his career with the NAACP and brought a completely unique perspective to the bench due to that work, significantly advancing equal protection jurisprudence. In reflection, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote:

Although all of us come to the Court with our own personal histories and experiences, Justice Marshall brought a special perspective. His was the eye of a lawyer who saw the deepest wounds in the social fabric and used law to heal them. His was the ear of a counselor who understood the vulnerabilities of the accused and established safeguards for their protection.15

In discussing the legacy of her former colleague, Justice O’Connor rightfully does away with the notion that judges can—or should—somehow divorce their understanding of the law from their lives. A bench made up of individuals with diverse perspectives results in a stronger jurisprudence that recognizes diverse sets of people and the realities of their lives.

In another examination of professional diversity, Alliance for Justice, a progressive judicial advocacy group, explains: “When a judge decides whether a claim is ‘plausible,’ or whether a witness is ‘credible,’ or whether police officers, when they stopped and searched a pedestrian, acted ‘reasonably,’ her determination is necessarily influenced by the nature of her work as a lawyer up to that point.”16

Conservatives have long decried the idea of an “activist” judge.17 And while judges from nonprofit backgrounds and government public defender settings are often stereotyped as activists because of the populations they represent, nominees from law firm settings—not coincidentally, often white men—are largely assumed to be free of any bias.18

This notion lacks logic given that a corporate lawyer’s training has occurred in a setting with no less of a focus than a nonprofit organization may have; lawyers at private law firms typically work to further business interests. In fact, it is a defining characteristic of the legal profession that a lawyer “zealously”19 represent the interests of their clients. Over the course of a legal career, a lawyer learns about statutes, guidance, legal philosophy, and precedent grounded in the perspective of advocating for that client—whether that be a young family or a large corporation. Recognizing this is not a condemnation of a corporate lawyer over a public interest lawyer; rather, it is acknowledging that both sets of lawyers will bring different types of expertise and skills to the bench.

By accepting that fact, particularly in light of the professional disparities discussed below, the need for greater professional diversity on the bench becomes clear.

Much has been written about the makeup of the U.S. Supreme Court. While the author touches on the characteristics of those who sit on the highest court , this report will focus on judges sitting on the 12 regional circuit courts, in addition to the Federal Circuit, that make up the U.S. Courts of Appeals.

The data paint a clear picture of the typical appellate judge: white, male, and from a private practice background. He typically has more than 20 years of professional experience between graduating law school and his first federal judicial appointment, and it is overwhelmingly likely that he attended an elite law school—even if he is not included in the full quarter of the appellate bench that attended Harvard or Yale.

Looking outside this stereotype, a more complex picture emerges on how those who do not fit this stereotype gain the prominence in the legal world needed to attract a nomination to the federal bench. Out of the 12 women of color on the appellate bench, for example, only one attended Harvard or Yale.

And for those individuals who choose a career path outside of a law firm or government setting, there appear to be near-insurmountable obstacles to the bench. Only one circuit judge spent the majority of his career in nonprofit work, such as at a civil rights, workers’ rights, or legal aid organization.

The following section first looks at notable characteristics of the current Supreme Court to set the stage for understanding what the legal profession, and those tasked with selecting judges, appears to value most in the backgrounds of judges. The report then turns to a deep dive on three key areas in the journey from law student to an appellate federal judge: legal education, clerkships, and professional experience.

The U.S. Supreme Court

As would be expected, the Supreme Court is made up of individuals from elite backgrounds. All justices attended extremely prestigious law schools, and all had distinguished careers before becoming federal judges—either in private practice, government, or legal academia. Even Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, rightly well-known for her work at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to advance women’s rights, spent the majority of her career before the bench as a law professor.

Only three law schools are currently represented on the bench: Columbia, Harvard, and Yale. Justice Ginsburg is the only active justice to attend Columbia; the rest went to either Harvard or Yale. Additionally, it is likely worth mentioning that Justice Ginsburg spent the majority of her law school years at Harvard before transferring to Columbia. When living, retired justices are included in that count, the number expands by only one school: Stanford.

Politics and the Supreme Court

While President Trump’s most recent appointment to the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh, is notable for spending the majority of his professional career engaged in the Whitewater investigation and later as a presidential aide, the justices as a whole generally did not shy away from political roles before joining the bench. Half of the living justices either worked in the White House, U.S. Congress, or as elected officials themselves. Those positions include Justice O’Connor’s significant time as an Arizona state senator and Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Clarence Thomas’ time as U.S. Senate staffers. In addition, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Kagan and Kavanaugh all served as White House staffers for U.S. presidents.

Such experience underscores the nonsensical nature of the bias against attorneys from public interest sectors. Given such political work, any of these justices could be seen as having an agenda they seek to implement on bench, yet all were nominated despite those roles.

Notably, the more senior living justices generally did not serve as clerks to judges as young lawyers while the more junior members had multiple clerkships. The most recently appointed justice, Brett Kavanaugh, held three clerkships. A notable break from this trend is Justice Sonia Sotomayor—also the only woman of color on the bench—who is the only justice nominated in almost 30 years who did not hold a clerkship. As will be explored below, federal clerkships are highly competitive, and clerks themselves are typically from very elite schools and from nondiverse demographic backgrounds—a trend in the legal system that significantly contributes to a lack of professional diversity.

As illustrated below, the backgrounds of Supreme Court justices reflect many of the trends observed in the lower appellate courts.

The U.S. Courts of Appeals

Only a very small fraction of cases will be heard by the justices on the Supreme Court.20 As a result, the federal appeals courts are most parties’ last opportunity to make their case. These seats are considered extremely prestigious and are distributed across the country in the 12 regional circuit courts—the 1st through 11th and the D.C. circuits—as well as the Federal Circuit. The trends in legal education, clerkships, and professional experience discussed below are by and large consistent from circuit to circuit.

Law schools

Much has been written about the prevalence of elite law schools being represented on the bench in recent years, reflecting the influence a law school can have on a future attorney’s career—particularly if that attorney wishes to one day join the bench.21 As respected legal commentator Dahlia Lithwick wrote: “[E]lite schools beget elite judicial clerkships beget elite federal judgeships. Rinse, repeat.”22

In fact, while the prevalence of elite schools on the bench generally is clear, just two law schools—Harvard and Yale—have educated approximately one-quarter of the appellate bench. Expanding the scope slightly to include the schools that all living current and former Supreme Court justices attended—meaning that judges who graduated from Columbia and Stanford are added—the number of appellate judges who graduated from the same schools as recent Supreme Court justices includes approximately 30 percent of the federal judiciary.

Certainly, these law schools provide an exceptional legal education. But just as certainly, they grant their students myriad professional connections and access to powerful fellow alumni that even the most brilliant student from a less elite school would find difficult to access.

With those professional benefits in mind, it is important to note that the proportion of appellate judges who are women, particularly women of color, who attended these schools may be much lower than the proportion for the bench as a whole. In fact, only two of women of color on the appellate bench—less than 20 percent—attended a so-called SCOTUS school.

Clerkships

As the above quote by Lithwick illustrates, one of the most coveted positions after law school is a federal clerkship. In fact, the importance—or at least, likelihood—of a potential federal judge holding such a credential seems to be increasing. Furthermore, it appears that some of the most elite clerkships are increasingly going to students with conservative political leanings. Taken together, trends in clerkships appear to be a significant barrier to fostering diversity on the bench.

Reflecting trends among the older and younger Supreme Court justices, while approximately just one-third of senior appellate judges clerked, about two-thirds of active judges completed at least one clerkship early in their careers. Among those with two judicial clerkships, nearly all are more recent appointees. The highest number of clerkships that any sitting federal judge completed is three, and every judge with that number was nominated by either President Barack Obama or President Trump.

Thanks to growing financial incentives from the private sector paired with rising tuition rates and student debt, it would appear that clerks are increasingly incentivized to join large corporate law firms after leaving their clerkship. These clerks collect large, continually increasing bonuses from their new employer: today, typically at least $50,000 and more than $100,000 at some firms for a clerk at the district or appellate level. A clerkship on the Supreme Court can typically enjoy a bonus of $400,000 from large firms,23 and multiple federal clerkships come with additional bonuses.24

This trend, however, appears to be benefiting individuals already overrepresented on the bench. For example, of those seven individuals with three judicial clerkships, all are white, and only two are women.

The power of conservatives in the judicial pipeline and judgeships

The type of insider access that firms hope to purchase by attracting clerks also speaks to the fact that a clerkship can go far in helping a young lawyer develop the insider relationships and network that could significantly help lay the groundwork for a future nomination for a judgeship. In addition, students—particularly at the appellate and Supreme Court levels—tend to apply to clerk for judges who align with their own legal theology or political leaning, while judges tend to hire individuals from similar backgrounds, particularly in regard to education and politics, as their own. Closely related to professional diversity, such hiring practices can undermine intellectual diversity in regard to personal ideology as well. And currently, the pipeline appears significantly skewed toward those with conservative political views.

Looking at what is considered the most prestigious clerkship experience makes this trend clear. The majority of former Supreme Court clerks now serving as appellate judges across all demographic groups worked for justices appointed by Republican presidents—typically a sign that that justice’s jurisprudence, as well as their clerks’, aligns with a conservative viewpoint.

The Federalist Society’s influence on the judicial pipeline

The decades-old Federalist Society has worked to develop a pipeline of conservative candidates for judgeships—often beginning with securing the loyalties of law students through networking events with prestigious law firms and federal judges. Founded in 1982, the organization’s full name is the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies. The Federalist Society has hundreds of chapters of lawyers and law students across the country and dedicates itself to promoting an extreme, conservative understanding of the law while encouraging its members to involve themselves in local, state, and federal public policy.25

The organization holds events that cast itself as diametrically opposed26 to progressives while fostering candidates for judges who hold far-right positions in regard to civil rights. Supported by wealthy and anonymous donors,27 conservative organizations such as the Federalist Society have been extremely effective in their efforts to influence powerful legal figures. For example, of the five current Supreme Court justices nominated by Republican presidents—Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice John Roberts—all have close ties to the Federalist Society.28

During the 2016 campaign, President Trump pledged that all his candidates would be approved by the organization. To date, at least 85 percent of his appellate federal judicial nominees are active members in the Federalist Society.29 As is illustrated by the clerkship trends discussed in the rest of this section, the grip the organization and its funders have on the judiciary has the potential to continue for decades.

This conservative bent among those Supreme Court clerks who make their way back to the federal bench is further illustrated by the fact that, among all current and retired living justices, Justice Thomas has the highest number of former clerks serving as circuit court judges. Justices O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy are tied for second, followed in order by Alito, Ginsburg, and David Souter. Furthermore, while the most recently appointed justices—Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh—would not be expected to have former clerks who worked for them on the Supreme Court serving as a circuit court judge due to their young age, two former clerks for Kavanaugh from the D.C. Circuit and one former Gorsuch clerk from the 10th Circuit are now appellate judges.

Professions

While alma maters and clerkships may provide the foundation for a legal career, lawyers develop their expertise and understanding of the law through their professional experiences. This section breaks down the broad career paths, along with some notable subcategories, of all federal appellate judges—defined by the sector in which they spent the majority of their career before becoming a judge at any level.

Prior judicial service

After their work as lawyers, many appellate judges—approximately 30 percent—served as a judge on the federal district level for significant time before being elevated to the appellate courts. Roughly the same percentage served in non-Article III judgeships, such as on state courts or federal courts that do not carry a lifetime appointment, before joining the appellate bench.

The following four sectors are discussed in descending order of percentage of the entire bench: private practice, federal government, state and local government, and legal academia. The final section discusses judges from other careers—making up approximately 3 percent of the bench overall. This number includes the one judge, Judge Richard Paez, who spent the majority of his career as a legal aid attorney. Judge Paez worked at a variety of legal aid organizations, most extensively at the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles. And while it would be a mistake to wholesale apply stereotypes about a given profession to every judge with that background, as several examples below make clear, these categories demonstrate the overwhelming dominance certain legal sectors have on the bench.

Finally, it is important to note the evidence suggesting that the bench is beginning to diversify somewhat: While more than 70 percent of senior-status judges come from private practice backgrounds, less than 60 percent of active-status judges come from this professional sector, explained largely by the significantly growing proportion of judges being selected from government backgrounds. At the same time, federal prosecutors dominate among those judges from government sectors, limiting the impact of that change in regard to broad increases in diversity. That trend, however, seems to be in lockstep with the slow demographic diversification occurring far too generally within the judiciary.30 For example, more than one-third of all male judges on the bench who come from communities of color spent the majority of their careers within government, compared with less than one-quarter of white men.

Despite that shift, the lack of professional diversity remains stark.

Private practice

As noted previously, the appellate bench is stacked with individuals from private practice backgrounds—particularly men from all race and ethnicities, who are significantly more likely than women to be from this professional setting. Nearly two-thirds of circuit court judges spent the majority of their careers in private practice. The proportion of white male judges and male judges from communities of color from this field is close to 70 percent for both groups. That proportion drops to less than 60 percent of the white women on the bench and less than half of women of color—speaking to the continuing discrimination women face when rising through the ranks of many law firms.31

Many circuit court judges made their careers in smaller firms, but significant numbers established careers at international corporate powerhouse firms—also known as BigLaw—such as Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP,32 Jones Day,33 and O’Melveny & Myers LLP.34 These types of firms focus their work on large corporations able to afford the extremely high fees that come with retaining such firms.35

Furthermore, while a small number of judges from this category appear to have been engaged in private public interest law,36 overwhelmingly, appellate lawyers who spent the majority of their careers engaged in private practice worked for business-focused firms, even if not at one of the powerhouse firms noted above. These firms, while perhaps occasionally handling personal matters for certain high-income clients, derive the vast majority of their revenues from business transactions—mergers and acquisitions, corporate governance, and equity and debt financing37—as well as large-scale litigation representing the interests of corporations.

Trailblazers in BigLaw

It should be noted that several former BigLaw partners who are now on the appellate bench, particularly women and people of color, gained prominence at their firms during a time when they had little to no established support networks. Those experiences, and what they may speak to regarding these judges’ perspectives on power and discrimination, are essential to recognize within a discussion of professional diversity.

A strong example of such a trailblazer is senior 2nd Circuit Court Judge Amalya Lyle Kearse. Judge Kearse was the only Black woman in her law school at the University of Michigan, where she was an editor of the law review and graduated cum laude in 1962 before joining one of the most prestigious firms in the country, Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP. She became the first female Black partner not only at her firm but at any major so-called Wall Street firm.38

She is also a championship bridge player and served on the board of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund earlier in her career.

While many of these attorneys also likely engaged in pro bono legal work and other activities that were valuable in informing their understanding of the law, the strong majority of those on the appellate bench have expertise that was gained through the lens of advancing the interests of businesses.

Federal government

The second-most represented sector is the federal government. The majority—more than 60 percent—of those judges spent the bulk of their careers within the federal government as prosecutors. Only one spent the majority of her career as a federal public defender.

Several of these judges held other positions throughout the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), and still others in this category spent the majority of their careers in the military or at other federal agencies, such as the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

White male judges in this category are less likely than judges from other demographics to have spent the majority of their careers in federal government. In fact, male judges from communities of color are the demographic group most likely to have worked within federal government for the bulk of their careers, with the most common career path being a prosecutor. The role of federal prosecutor was also the most common career path among all female judges who spent the majority of their careers in federal service.

State and/or local government

The third-most represented sector is made up of individuals who spent the majority of their careers in state and/or local government. Unlike their federal counterparts, however, the majority of these judges spent their government service careers in roles other than a state or local prosecutor. Most common was a variety of different roles within a state attorney general’s office, with careers within a governor’s office or as a city or state solicitor also being common.

Finally, the number of judges who spent the majority of their careers as public defenders at the state level, including Washington, D.C., doubles the federal number—albeit from one judge to two.

Women in general are more likely than men to have worked at the state or local level, with a full one-third of judges who are women of color having spent the majority of their careers in such roles and white women ranking second-most likely to have done so.

Law professors

Finally, significant numbers of current appellate judges came from legal academia—though slightly fewer than those who served in state and local government—often with very little experience practicing law before becoming professors. Arguably in tension with conservative claims that law schools are dominated by progressives, the majority of appellate judges on the bench who came from academia were appointed by Republican presidents.

Many judges have diverse careers that are not easily defined

D.C. Circuit Court Judge Cornelia Pillard’s career is an excellent example of the varied nature of many federal judges’ backgrounds, even when one sector clearly dominates their career history. While the vast bulk of Judge Pillard’s career was in academia, she started her career at the ACLU and NAACP and later spent time in the DOJ.

Moreover, in contrast to the stereotype of the ivory tower academic, Judge Pillard argued or briefed dozens of cases before the Supreme Court and litigated cases in trial courts as well. As co-director of Georgetown Law’s Supreme Court clinic, she helped prepare lawyers who represented diverse interests for oral arguments on a wide variety of topics.39

Republicans in the Senate initially blocked Pillard, an Obama nominee, from being appointed, decrying her academic writings for being “outside of the mainstream.”40 Conservative activists piled on, claiming she supported “militant feminism.”

Male judges from communities of color are significantly less likely than any other demographic group to hail from legal academia. White women are somewhat overrepresented, with the proportion of white men and women of color falling below the overall proportion of the bench in respective order.

The rest of the bench

The remaining judges not included in the categories above make up approximately 3 percent of the appellate bench. In addition to Judge Paez, who spent his career in legal aid, this percentage includes judges who spent the majority of their careers engaged in general business roles outside of the law or serving as in-house lawyers within large institutions, including major universities.

This report breaks out these lawyers for illustrative purposes to show the very small number of individuals who make their way to the bench from careers spent in any setting outside the larger categories described above. However, there is a strong argument to view these judges as a subcategory of those coming from private practice, given the practice areas are strongly aligned between the two groups as both sets are focused on business interests.

Where are the public interest lawyers?

Taken together, only about 1 percent of all circuit court judges spent their careers as public defenders or legal aid attorneys. Only three appellate judges spent the majority of their careers as lawyers as state or federal public defenders: Judges Bernice Donald on the 6th Circuit, Jane Kelly on the 8th Circuit, and Robert Wilkins on the D.C. Circuit. And, as noted above, only one spent his career in a nonprofit setting: Judge Richard Paez from the 9th Circuit Court, who spent his career as an attorney with the California Rural Legal Assistance and the Western Center on Law and Poverty, in addition to the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, before becoming a municipal court judge.

There is no sitting appellate judge who spent the majority of their career with nonprofit, civil rights organizations as Justice Thurgood Marshall did.

Looking beyond judges who spent the majority of their careers in these settings, it is clear that only a handful of appellate judges have any career experience with such organizations. Less than 10 appear to have spent any time at legal aid organizations or as a public defender. As two final examples, Justice Ginsburg is joined by only two appellate judges with any time spent at the ACLU, and only one spent time at the NAACP. No sitting appellate judge has spent the majority of their career at a women’s rights organization, a child welfare organization, an immigration rights organization, a labor union, or a disability rights organization.

Finally, the only judge not represented in any of the categories above is Judge Helene White. After graduating from law school, White worked as a clerk for the Michigan Supreme Court before successfully running for a state judgeship, remaining a state judge until her appointment to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in 2008.

As has been observed and commented on by a variety of sources, both progressive and conservative,41 the data in this report confirm that the appellate bench is overwhelmingly dominated by individuals who spent their careers engaged in corporate business-focused practices and, to a lesser extent, as federal prosecutors. And while professional diversity in recent years has improved in strong correlation with demographic diversity on the federal bench, this report underscores the severity of the lack of attorneys from civil rights, legal aid, and public defender backgrounds across the federal judiciary.

In evaluating the information presented in this report, several important trends emerge—notwithstanding the obvious dearth of individuals from nonprofit and public defender fields—that must inform future reforms to bring greater diversity to the bench:

- Improving professional diversity cannot be done without any eye to what takes place in the early years of a lawyer’s career. Law schools and clerkships set the stage for a promising attorney to ultimately gain the connections and prestige in their field needed to secure a future nomination to the federal bench.

- Relatedly, the rise in the importance of multiple, elite clerkships and the powerful monetary incentives to enter private practice after those clerkships serve to undermine efforts to improve professional judicial diversity. Any effort to address this issue must also recognize the reality that many students face significant difficulties in paying off student loans from law school.42

- Partisan conservatives currently have an outsized influence on the pipeline for federal judges, threatening to undermine intellectual diversity along with professional diversity.

- The link between professional and demographic diversity is complex. Women and people of color are much more likely to come from government than from an international law firm; thus, selecting more judges from the former is likely to increase both professional and demographic diversity. Moreover, for many attorneys—particularly for women and people of color—this correlation is unlikely to come from choice but rather from continuing prejudices, both overt and subtle, within elite firms. Any reforms to encourage professional diversity on the bench should not be confused with allowing such discrimination to continue nor with discounting the important perspectives of those who become prominent partners in law firms despite such continuing biases.

The entire legal profession, including entities such as the American Bar Association (ABA) and law schools, have a role to play in the promotion of individuals from diverse career settings into judgeships. In addition, policymakers must advance reforms in order to improve the current state of affairs .

Pipeline-focused reforms: Legal education

It is clear that law schools play a significant role in the early years of a lawyer’s career. To leverage that influence and help foster more professional networks for their students, law schools should be required to ensure that more students are exposed to the judiciary—and to judges—through new curriculum requirements.

The ABA sets the standards in regard to law school accreditation, including curriculum standards.43 Similar to the current requirement for schools to mandate a class on professional responsibility and courses providing “writing experience,” schools should also be required to craft a class on the judiciary that all law school students would take as a prerequisite for graduation. Such a course offering should cover both the judicial system in the school’s home state and the federal judiciary. While the class would provide an overview of how the state and federal judiciary operate—from trial to appellate—it would also emphasize how judges at both levels are selected as well as how chambers are generally run. Furthermore, similar to guidance it provides on other curriculum requirements, the ABA should strongly encourage schools to recruit sitting or senior-status judges to either teach the class or otherwise meaningfully engage with students. Given that many law schools already engage judges as adjuncts or in other advisory roles, such a standard should not pose a significant burden.

The goal of such a course would be twofold. First, and for the purposes of this report, such a requirement would give students who may not secure a future clerkship networking opportunities with judges in addition to some insight into the judiciary and practicalities of a judge’s chambers. Second, in keeping with the ABA’s objective of ensuring schools provide a “rigorous program of legal education,” such a course could strongly inform a young lawyer’s understanding of the court systems in which many—if not most—will be practicing upon graduation.

Pipeline-focused reforms: Clerkships

The clerkship process must also be reformed to improve diversity on the bench in the long term. While a clerkship should not continue to be viewed as a de facto requirement to becoming an appellate judge, it is at the same time inarguable that clerking can provide a young lawyer with significant access to influential networks that can benefit them professionally in a variety of ways. Recognizing this reality, the courts and Congress could take direct action improve this aspect of the judicial pipeline in terms of professional diversity.

As one example, policymakers should explore reforms that would result in district and circuit courts hiring clerks to work for the court itself as opposed to specific judges. Creating hiring committees tasked with attracting a diverse pool of candidates, including demographic and educational diversity and with attention paid toward candidates who have spent one or two years practicing law in underrepresented fields, could go far in ensuring that a broader set of talented law students and recent graduates are able to benefit from clerkships. And by being hired and working for the court itself, clerks would be able to take assignments from different judges—meaning they would have the opportunity to work with judges of varying educational, professional, and ideological backgrounds and form relationships with more judges than they would have previously.

To be clear, such a reform would significantly change the nature of the work a clerk currently conducts for one specific judge. Given, however, that the current system of clerking is a relatively new invention by the judiciary44 and that the system appears to have undesired consequences, such changes are worth considering.

When considering what influence Congress could have in this regard, it is important to keep in mind that appropriators control the budget of the federal judiciary. In recent years, appropriators have discussed policy issues such as whether or not to authorize new judgeships at the district and appellate levels as well as how to institute more transparency into the workings of the federal judiciary.45 Enacted as part of the Financial Services and General Government appropriations bill, appropriations for the judiciary include mandatory funds, such as the salaries of federal judges, as well as discretionary funds for the administrative functioning of the courts.46

Pipeline-focused reforms: Making public interest work affordable

In addition, policymakers should make a career in public interest work more affordable for young lawyers. As a clear initial step, Congress should invest in more robust loan forgiveness programs for all students, including young lawyers.

At the same time, policymakers should consider additional reforms, such as exploring how Congress’ taxing power could be used in a way that would help more young attorneys afford to dedicate their careers to public interest work. As one possibility, policymakers could explore ways to incentivizing high-revenue law firms to award public interest grants. A good example of the impact of such a policy can be found in the international law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP. Skadden has instituted a well-regarded program to support public interest work, where talented young attorneys receive a modest two-year salary to support their employment. Upon conclusion of the fellowship, 90 percent of participants stay in the nonprofit sector.47

Additional investments into public service work generally, encouraged by federal policymakers, could further allow talented lawyers to remain committed to public interest work.

Future nominees

Finally, it is imperative that future nominees for federal judgeships come from diverse professional backgrounds.

This does not mean that the administration should only consider individuals from certain professional backgrounds; doing so could risk disqualifying eminently qualified individuals, perhaps most troublingly from communities underrepresented in those sectors. But while pipeline reforms are important in regard to long-term gains, it is essential that future administrations commit themselves to nominating those who have dedicated their careers to civil rights and legal aid organizations as well as those who have served as public defenders.

In addition, prioritizing the selection of judges from certain career fields is not enough to truly broaden the bench. Future administrations must also nominate distinguished alumni from schools other than those already enjoying extremely strong representation on the bench. Given the loyalty of many judges to their alma maters,48 doing so would also likely encourage the hiring of clerks from a greater number of law schools, helping to further diversify the pipeline of judges.

A future administration could set two goals. First would be a commitment to nominating a significant number of judges from underrepresented fields. Second, an administration could set a similar goal in regard to educational diversity. For example, it could aim to ensure that a number of its nominees have attended a law school located within the region of the circuit that judge is to serve.

Regardless of any goal set for the bench as a whole, any future administration should also commit to installing diversity into the highest Supreme Court vacancies with lawyers from careers dedicated to nonprofit or public defender work as well as those who attended a school other than one already represented on the bench.

A future administration could set up an independent commission to lift up the need for more diversity on the bench and track diversity metrics to ensure effective implementation of these goals. And while the next president should ensure those within the administration charged with managing the judicial nomination process are committed to advancing diversity, it may also be helpful for such a commission to aide those officials in their work by spearheading new initiatives to help identify and vet attorneys who would not have otherwise been considered for judgeships. President Jimmy Carter, for example, set up such a body to aid him in the selection of his judges.49 But it is important to recognize that any commission of this sort would not be binding on a president without a constitutional amendment.

Therefore, it is up to the integrity of future administrations to stay committed to the furtherance of professional diversity on the bench.