Introduction and summary

More than a dozen states are denying their own residents expanded access to Medicaid, despite the fact that the federal government would pay for nearly the entire cost under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Medicaid plays a critical role in Americans’ access to health care, paying for half of all births in the United States,1 providing resources to combat the opioid epidemic, and helping keep rural hospitals financially afloat. Evidence shows that in states that have implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, low-income populations have benefited from not only better access to care but also greater financial stability, fewer evictions, and lower poverty rates.2

While Medicaid enjoys strong public support, officials in a handful of states are refusing to act in the interests of their own citizens. Many of these states have failed to expand Medicaid because of partisan gerrymandering—the practice of drawing district lines to unfairly favor particular politicians or political parties.3 By gerrymandering their districts, politicians can stay in power—and keep their political parties in power—even if they lose voter support. And that means that on issues such as the expansion of Medicaid, conservative politicians can cater to the extreme right wing and oppose policies that would save lives at minimal cost to state taxpayers.

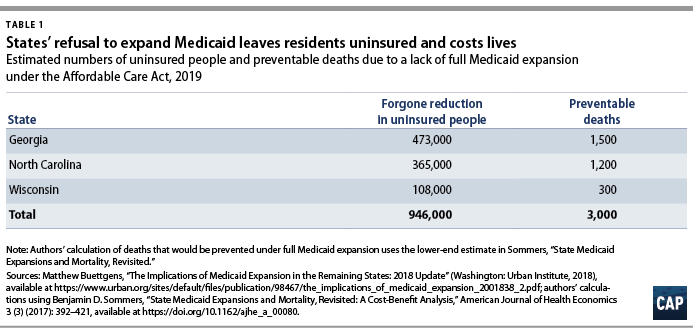

The cost of this distortion is high. In North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Georgia—three states that have not expanded Medicaid—1 million more people would have been insured and roughly 3,000 deaths would have been prevented in 2019 alone if the expansion had been fully implemented. In Michigan—another state with heavily gerrymandered districts—conservatives in control of the Legislature have attempted to limit beneficiaries’ access to Medicaid through the imposition of burdensome work requirements. Evidence shows, however, that Medicaid work requirements not only result in low-income people losing health coverage but also fail at their purported objective of boosting employment.

Gerrymandering affects everything that legislatures do by shifting who gets elected in the first place. A 2019 report from the Center for American Progress demonstrated how gerrymandering has stopped state legislatures from taking action to prevent gun violence, blocking the passage of popular, commonsense measures such as universal background checks and extreme risk protection orders.4

This report analyzes the relationship between gerrymandering and Medicaid policy. The first section explains two common state efforts to limit access to health care: 1) refusing to expand the state Medicaid program to provide low-income adults access under the ACA and 2) initiatives to take coverage away from beneficiaries who do not meet burdensome work requirements. The subsequent section highlights four states where data show that gerrymandering likely played a key role in restrictions on Medicaid eligibility: North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Georgia.

The final section of the report provides a policy solution: voter-determined districts.5 As detailed in previous CAP work, districts should be drawn by independent commissions that have a mandate to draw them in a way that accurately reflects voter preferences. Importantly, these commissions should draw districts that ensure representation for communities of color, who have long been pushed out of the political process.

A fair process for drawing districts is fundamental to democracy, helping to ensure that voters’ voices are heard on critical issues such as access to health care.

Despite its popularity, some states are restricting eligibility for Medicaid

Medicaid is a public program that provides health insurance to low-income Americans. Traditionally, the target population has been low-income parents, children, disabled people, and elderly people. Nationwide, about 75 million people are enrolled in Medicaid, including nearly 13 million who gained eligibility through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion.6 More than two-thirds of Americans report that they have either been covered by Medicaid themselves or have had a close friend or family member who was a Medicaid beneficiary.7 Unsurprisingly, then, Medicaid is popular with voters across both major political parties. Nationally, 74 percent of Americans have a favorable view of Medicaid—including 82 percent of Democrats and 65 percent of Republicans—while only 20 percent of Americans have an unfavorable view.8 Even in states that have not expanded Medicaid, 59 percent of respondents in a 2018 poll favored “expand[ing] Medicaid to cover more low-income uninsured people.”9

States and the federal government share Medicaid costs based on a formula that accounts for the average income of state residents, with the federal government paying a minimum of 50 percent of the total costs for each state.10 Within certain guidelines, each state has the latitude to modify eligibility criteria and determine which benefits to provide.11

Starting in 2014, the ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level and guaranteed that the federal government would bear at least 90 percent of the costs of covering the newly eligible population. While the ACA originally called for expanding Medicaid nationwide, a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling made expansion optional for states.12

Some states are refusing to expand Medicaid

Despite the generous federal funding available, many states have refused to implement the expansion. As of February 2020, 14 states still have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA.13 As a result, more than 2 million uninsured people are stuck in the so-called coverage gap: They are too poor to qualify for subsidized private coverage through the ACA marketplaces but have incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid.14

Politics aside, the refusal of these states to fully expand Medicaid is illogical because of not only the opportunity to dramatically increase coverage at low cost to state taxpayers but also the mounting evidence that expanding Medicaid improves health outcomes and lowers mortality rates. According to earlier CAP estimates, the 14 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid pay a high price in human lives: Expanding the program would allow them to collectively avoid more than 13,000 deaths each year.15 A study from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that from 2014 to 2017, Medicaid expansion saved an estimated 19,000 lives among older adults ages 55 to 64.16 Medicaid coverage can also improve maternal and infant health, an area where the United States lags behind its peer nations. States that expanded Medicaid subsequently had lower rates of mortality among both mothers and babies.17

A large body of research shows that Medicaid expansion can improve people’s lives in other ways too, including those of family members and others not directly affected by the ACA’s more generous eligibility thresholds. Medicaid expansion is associated with lower rates of housing evictions among low-income families,18 lower rates of medical debt, and higher rates of satisfaction with household finances.19

Medicaid has also been a critical program in the fight against the opioid epidemic. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation report, in 2017 nearly 40 percent of the almost 2 million nonelderly adults with an opioid use disorder were covered by Medicaid.20 Medicaid allows states to provide treatment and early intervention to those in need, and Medicaid expansion allows states to extend treatment to more people with opioid use disorder. A recent study found that Medicaid expansion may have prevented as many as 8,132 opioid overdose deaths from 2015 to 2017.21 The contribution of Medicaid expansion toward combating opioid addiction has been recognized on both sides of the aisle: As then-Ohio Gov. John Kasich (R) noted about his state, “Thank God we expanded Medicaid because that Medicaid money is helping to rehab people.”22

By covering millions of people previously uninsured or underinsured, Medicaid expansion has reduced hospitals’ costs of uncompensated care,23 helping bolster the financial sustainability of rural hospitals in particular. In rural areas, hospital closures can exacerbate problems with access to care and increase patients’ travel times for emergency care.24 Yet while more than 121 rural hospitals have closed since 2010 due to strained finances and changes in the hospital industry,25 a 2018 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that states that expanded Medicaid eligibility and enrollment were less likely to experience rural hospital closures.26

Some states are trying to institute burdensome work requirements

Another worrying trend in Medicaid policy is that some states are taking away their residents’ coverage for not meeting burdensome work requirements. Among the states that have expanded Medicaid, some have sought waivers from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to allow them to limit eligibility or benefits and to increase cost-sharing. A total of 20 states have requested waivers so that they can take coverage away from beneficiaries who do not meet rigid work requirements—an approach that the Trump administration has actively pushed.27 However, a recent decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit casts doubt on the legality of work requirements.28 The court found that the approval of Arkansas’ work requirements was invalid, because the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services failed to consider what impact those requirements would have on the central purpose of Medicaid: providing health insurance to those who cannot afford it.29

Instituting Medicaid work requirements worsens health outcomes, generates administrative burdens for state agencies and beneficiaries,30 and fails to achieve the purported goal of increasing employment.31 In Arkansas, 17,000 people lost Medicaid coverage due to work requirements in the first year that the requirements were in effect, despite the fact that a survey of that group found that 95 percent either met the requirements or qualified for an exemption. This suggests that many people who lost coverage were simply caught up in red tape.32 Work requirements are confusing and impose overly burdensome reporting requirements on beneficiaries.33 Outreach in places such as Arkansas has failed to adequately educate those subject to the requirements.34 Moreover, some Medicaid beneficiaries who are disabled may not qualify for an exemption on the basis of disability and thus face additional difficulties fulfilling work requirements—and may be denied needed coverage.35

Although work requirements are intended to target unemployed adults, the policy can hurt children whose parents lose coverage. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities explains:

When parents lack health coverage, children are also more likely to go uninsured. Children also benefit directly when their parents can access the health care they need and have greater financial security, which is why parents losing coverage hurts children’s health and long-term development.36

Despite the many benefits of Medicaid—and the high rates of public support for the program—political leaders in 14 states are refusing expansion or are supporting taking coverage away from people who do not meet work requirements. The bulk of the resistance seems to be coming from conservative lawmakers who have an ideological opposition to the ACA and government programs—and who are unwilling to make an exception for a program that would improve lives at a relatively low cost to state taxpayers.

That is not to say that all conservatives have rejected Medicaid or insisted on work requirements. To the contrary, even some deep-red states such as Louisiana and North Dakota have fully implemented Medicaid expansion without work requirements.37 However, every state that has rejected Medicaid expansion has had consistent Republican control of its legislature since at least 2014.38

Yet not every state with a Republican-controlled legislature is overwhelmingly made up of Republican voters. In fact, several of the states that have rejected or restricted Medicaid eligibility are states in which Democratic voters are either a majority or close to half of the voting population. In these states, partisan gerrymandering is the only consistent explanation for why legislators are denying health care to their own state residents.

How partisan gerrymandering has undermined Medicaid expansion

Partisan gerrymandering is the manipulation of state lines to favor certain politicians. As explained in a recent CAP report:

At least once every decade, politicians redraw the lines of their electoral districts. Districts need to be adjusted to account for changes in population so that each representative still represents roughly the same number of people. However, politicians frequently take this opportunity to draw lines that benefit themselves and hurt their opponents. They strategically spread out supporters of their own party to get a majority in as many districts as possible while concentrating supporters of the opposing party in as few districts as possible. This is sometimes referred to as “cracking and packing.” If one party’s supporters are packed into few enough districts, the other party can sometimes win a majority of districts even when they receive a minority of the votes.39

In recent years, recognition of gerrymandering as a serious problem in American politics has finally started to gain traction. A number of states—including California and Arizona—have adopted reforms designed to prevent politicians from drawing their own unfair districts, turning that authority over to independent commissions instead.40 In 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a historic bill—H.R. 1—that would require all states to task independent commissions with drawing federal districts. However, the U.S. Senate, under Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), has refused to consider it.41

Unfortunately, in most states, the legislature still draws district lines, which allows incumbent politicians to engage in partisan gerrymandering.42 During the last cycle of redistricting that followed the 2010 census, Republicans controlled a large majority of state legislatures.43 This means that they had more ability to gerrymander than Democrats and were able to skew state election outcomes—and therefore state policy—in a more conservative direction. According to a previous CAP analysis, in the first three federal elections of the decade—in 2012, 2014, and 2016—gerrymandering resulted in an average of 19 more Republicans being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in each election than there would have been if districts were fairly drawn.44 If anything, that figure understates the extent of the problem, because it is the net result of gerrymanders that tilted in multiple directions—Republican gerrymanders, Democratic gerrymanders, and bipartisan gerrymanders. In bipartisan gerrymanders, states with divided control of government or redistricting commissions made up of partisan incumbents draw district lines in such a way as to prevent incumbents of both major parties from having to face electoral competition.45

All of these gerrymanders have affected policy outcomes, including state decisions about Medicaid. The most obvious impacts have been in states where unfair electoral maps have switched control of the legislature from Democrats, who have consistently favored Medicaid expansion, to Republicans, who have often favored rejecting expansion or imposing work requirements. However, even in states with a durable Republican advantage, gerrymandering can shift the balance of power from the more moderate Republican members—who may be more inclined to compromise—to members on the ideological extremes. These shifts have an effect even if they do not create Democratic majorities. Notably, every U.S. state where Democrats currently make up at least 42 percent of the members in both chambers of the legislature has expanded Medicaid.46

In each of the following four states—North Carolina, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia—gerrymandering appears to have been a decisive factor in blocking more residents from receiving Medicaid. In Georgia, North Carolina, and Wisconsin alone, fully implementing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion would have reduced the number of uninsured people by nearly 1 million in 2019, according to estimates by the Urban Institute.47 (see Table 1) Moreover, by improving access to health care, Medicaid expansion can save lives. A 2017 study by Harvard researcher Benjamin D. Sommers estimated that Medicaid expansion was associated with one fewer death for every 239 to 316 people who gained insurance.48 Applying the more conservative end of this range to the projected gains in coverage from Medicaid expansion, approximately 3,000 fewer people would have died in 2019 if the three states had fully expanded Medicaid.

North Carolina

North Carolina

Among the states that have not expanded Medicaid, North Carolina may be one of the most promising candidates for switching course.49 Expanding Medicaid has been a top priority for Gov. Roy Cooper (D) and has even received some conservative support.50 The state’s previous governor, Pat McCrory (R), said in 2014 that he would consider expanding Medicaid.51 And according to local media, a “growing number of conservative local leaders” are pushing for expansion.52 If the state had expanded Medicaid in 2019, an additional 365,000 people would have gained health insurance, according to estimates by the Urban Institute.53

However, many Republicans in the North Carolina Legislature—where, thanks to gerrymandering, they make up a majority—have so far adamantly resisted Medicaid expansion.54 North Carolina’s gerrymander was so aggressive that it landed the state—along with Michigan, discussed below—on the Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy’s list of the worst examples in the country of “minority rule.”55

In the 2018 state legislative elections, North Carolinians cast a narrow majority of their votes for Democratic candidates. Yet although Democrats received 51.2 percent of the vote for the state House and 50.5 percent of the vote for the state Senate,56 Republicans won a majority of seats in both chambers—54.2 percent of the seats in the House and 57.9 percent of the seats in the Senate.57 Had Democrats received a share of the seats commensurate with their share of votes—that is, a majority—they almost certainly would have expanded Medicaid. Thus, drawing fair districts would have ensured that hundreds of thousands of North Carolinians could gain access to health insurance.

Michigan

Michigan counts among several states with Republican-controlled legislatures that have opted to expand their Medicaid program. However, the Michigan Legislature also imposed work requirements with more demanding reporting requirements than even the deeply flawed work requirements imposed in Arkansas. Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D)—who has strongly opposed the work requirement—described it as one of the “most onerous” in the country and warned legislators that it could replicate the negative outcomes seen in other states.58 A 2019 Commonwealth Fund study estimated that the work requirements could result in as many as 233,000 Michiganders losing Medicaid coverage within the first 12 months after implementation, the largest loss among the nine states considered in the study.59

Nonetheless, Republican leaders in both chambers of the Legislature have refused the governor’s call to reverse the requirements, with state Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey (R) stating that they planned to “let the process play out.”60 However, like their counterparts in North Carolina, the only reason that Michigan Republicans are in power is that many were elected from districts that did not accurately represent Michigan voters.

In 2018, Michigan voters cast a majority of their votes for Democrats: 52.4 percent of the votes for state House and 51.3 percent of the votes for state Senate. Yet thanks to the unfair map that Republicans drew at the beginning of the decade, Republicans won a majority of seats in both chambers: 52.7 percent of the seats in the House and 57.9 percent of the seats in the Senate.61 If not for these heavily skewed maps, a Democratic majority would likely have heeded the governor’s call to reconsider work requirements.

Wisconsin

Although many states expanded Medicaid eligibility in response to the ACA, Wisconsin rolled back Medicaid coverage for low-income parents.62 Under former Gov. Scott Walker (R), the state declined to fully implement the ACA Medicaid expansion, instead extending Medicaid coverage up to only 100 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2013, Walker argued that he wanted “to have fewer people in the state who are dependent on the government,”63 yet his partial expansion scheme ended up costing taxpayers at least $1 billion more than if the state had fully implemented Medicaid expansion.64 In 2015, a bill to fully expand Medicaid was voted down in the Wisconsin Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee along party lines.65 In 2018, Wisconsin received approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to take coverage away from beneficiaries who do not meet work requirements,66 although the implementation of those requirements has been delayed until April 2020.67

Wisconsin’s 2018 elections demonstrated how gerrymandering can compound other anti-democratic practices to shift political outcomes. That year, Democratic candidates received 54.2 percent of the votes for the State Assembly—a clear majority.68 They also received 49 percent of the votes for the state Senate—a near majority, but not quite enough to control the upper chamber even with fair maps.69 However, Republicans won sizable majorities of the seats in both chambers—63.6 percent of the seats in the State Assembly and 60.6 percent of the seats in the Senate.70

In addition to this severe gerrymander, Wisconsin politicians were engaged in other aggressive tactics to manipulate the elections. As Wisconsin Democratic Party Chair Ben Wikler wrote in 2019, “For a while, Wisconsin has been ground zero for tilting the electoral playing field.”71 Under Gov. Walker, the state restricted voting hours and passed a harsh voter identification law that appears to have decreased voter turnout among students and communities of color—constituencies that have typically favored Democratic candidates.72

If Wisconsinites had a fair electoral process as well as fair districts, Democrats would have won a majority in the State Assembly, and it is highly likely that they would have won in the state Senate. With those majorities, they would have been able to fully expand Medicaid, providing 108,000 uninsured people with health coverage and at a lower cost to taxpayers. Current Gov. Tony Evers (D), elected in 2018, has said that he will “fight like hell” to expand Medicaid,73 but Republican legislative leaders have continued to firmly oppose any such change.74 Gov. Evers noted the ongoing resistance to the expansion in a recent State of the State address, saying it was one reason he was creating a shadow redistricting commission:

Well, when more than 80 percent of our state supports medical marijuana, 80 percent support universal background checks and extreme risk protection orders, and 70 percent support expanding Medicaid, and elected officials can ignore those numbers without consequence, folks, something’s wrong. The people who work in this building, who sit in these seats, and who drive the policies for our state, should not be able to ignore the people who sent us here. The will of the people is the law of the land, and by golly, the people should not take no for an answer.75

If Gov. Evers can succeed in carrying out the will of the people, 108,000 more Wisconsinites will be eligible for health insurance.76

Georgia

Georgia is another state that has yet to expand Medicaid, despite the fact that 473,000 more state residents would have health insurance if it did.77 Former Gov. Nathan Deal (R), whose term ended in 2019, stated early in his tenure that he had no “intentions of expanding Medicaid.”78 And in 2014, concerned about the possibility of a Democrat being elected after Deal’s term ended, Republicans passed a bill that ensured Medicaid expansion could not be accomplished without legislative approval.79 In 2019, however, after the election of Gov. Brian Kemp (R), the Legislature reversed course and gave Kemp the discretion to pursue other changes to the state’s Medicaid program—and did so over the strenuous objection of Democratic leaders who favored full expansion.80 In November 2019, Kemp proposed a very limited expansion of the state’s Medicaid program, expected to enroll only 52,000 people by its fifth year.81 This is in part because low-income Georgians would only be able to gain coverage if they demonstrate that they are meeting the state’s proposed 80-hour-per-month work requirement, which contains no exemptions.82 Kemp’s plan would cover roughly one-tenth of the people who would be eligible under a full ACA expansion of the program—and cost the state more than 50 percent more.83

Although Georgia has an increasingly narrow divide between Democratic and Republican shares of the vote, gerrymandering gave the latter party a larger majority, which in itself may have prevented Medicaid expansion. In 2018, Democratic candidates for the Georgia House and Senate both received almost exactly 45.6 percent of the vote,84 landing them within striking distance of a majority. But because of gerrymandering, Democrats received smaller percentages of the actual seats, winning only 42.1 percent of the seats in the House and only 37.5 percent of the seats in the Senate.

Note that even though these shifts did not affect control of the Legislature, they still may have influenced policy outcomes. Every seat matters: Parties with large majorities can pass highly partisan bills without worrying about losing too many votes, but parties with narrow majorities need to maintain the approval of their most moderate members in order to pass legislation. There is no way to know if Georgia, with fair districts and a 45.6 percent Democratic Legislature, would have passed a more comprehensive Medicaid expansion. But if it had not, it would have been the most evenly divided legislature in the country to opt against Medicaid expansion. Moreover, a poll of registered voters in Georgia found that 71 percent supported expanding eligibility for Medicaid.85

In any case, Georgia, like Wisconsin, has combined gerrymandering with some of the nation’s most brazen voter suppression; conservatives used both tactics in concert to inflate their political power. During the last election cycle, the person overseeing the election was none other than then-Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp—also a candidate in the close race for governor.86 Kemp stalled more than 50,000 voter registrations—disproportionately those of African American voters—and closed more than 200 local voting precincts, or about 8 percent of the state’s polling places.87 Some voters faced hours-long lines to cast a ballot.88 In addition, the state purged 1.5 million voters from the rolls between 2012 and 2016 and faced a slew of allegations of other modes of voter suppression and intimidation.89 These efforts almost certainly combined to decrease votes for Democratic candidates.90

The impact of gerrymandering—and how to fix it

Gerrymandering has an impact across most states and nearly every policy area.91 In the four states described above, its effects on the composition of legislatures are clear enough that they can be linked to particular policy outcomes. In many other states, gerrymandering combines with other factors to determine the political leanings of a state legislature. That makes for a more complicated story.

But even when gerrymandering does not affect control of a legislative chamber, it has a meaningful impact. There is a measurable difference in policy when a legislator from one party is replaced with a legislator from another.92 And that is happening—with shocking frequency—in statehouses across the country. For example, district boundaries for the U.S. House of Representatives are drawn in each state and thus are subject to gerrymanders. Nationwide, unfair maps shifted about 59 seats in the House from one party to the other in each election from 2012 to 2016—equivalent to changing the results of all the elections in the 22 least populous states.93 Often, the same people who are gerrymandering those maps are also drawing skewed maps for state elections.

All these gerrymandering effects add up to a significant amount of policy change—and this change is increasing the distance between legislators and the people whom they are supposed to represent.

Fortunately, this problem is solvable. Previous CAP work has proposed a solution: voter-determined districts.94 States should be required to draw districts that accurately reflect the political leanings of their citizens. For example, in a state such as Michigan, where slightly more than 50 percent of the vote was cast for Democratic candidates in 2018, slightly more than 50 percent of the districts should be represented by Democrats. And the composition of legislatures should be similarly representative in states where the voters lean Republican.

Furthermore, the power to draw districts should not be vested in incumbent officeholders. In most states, legislatures are charged with drawing the districts, which allows politicians to pick their own voters—a huge conflict of interest. A small but increasing number of states have instead given district-drawing power to an independent commission, removing incumbent elected officials from the process. All states should use independent commissions to draw their districts at both the state and federal levels.

Finally, district drawing has also been used as a tool to reduce the political power of communities of color, a practice known as racial gerrymandering. Communities of color continue to be underrepresented in state legislatures and in Congress—both because of racial gerrymandering and a long history of deliberate voter suppression and discrimination.95 Redistricting should be part of the solution by ensuring that districts are drawn in a way that gives communities of color fair representation.

Conclusion

Medicaid expansion is not a purely partisan issue. Although Democratic lawmakers have uniformly supported Medicaid expansion, many Republican lawmakers have supported it as well, to the benefit of their constituents.

However, because more conservative Republicans have led the charge in state legislatures to reject and restrict Medicaid expansion, it is one of the issues that helps illustrate partisan gerrymandering’s high costs. Ten years after the passage of the ACA, hundreds of thousands of people remain uninsured because of gerrymandering. Thousands of people will die prematurely each year because their state has refused to participate in a program to broaden access to affordable health care. Rural hospitals have been forced to close and states are less able to combat the opioid epidemic. Fair districts would have shifted the balance of power so that it better reflected the will of the people—and averted the needless suffering of low-income people who could have been covered by Medicaid.

When democracy works, legislators are faithful to the people they represent. Gerrymandering undermines the relationship between the government and the governed, with consequences across every issue of public concern—from inadequate health care to gun violence and far beyond. None of these problems can be responsibly and democratically addressed unless gerrymandering is addressed as well.

About the authors

Alex Tausanovitch is the director of Campaign Finance and Electoral Reform at the Center for American Progress.

Emily Gee is the health economist for Health Policy at the Center.